Cave of Forgotten Dreams

The thing about the sublime as an aesthetic (or religious) emotion is that you can only take it in small doses before it turns into unease and even fear. At one point in Werner Herzog’s new, amazing documentary about the astonishingly realistic Paleolithic paintings in Chauvet Cave in France, the filmmaker notes that he and his film crew—as well as those who had first discovered and explored the cave—experienced an uncomfortable and uncanny sense of being watched by those who had painted the wild animals on its contoured walls some 32,000 years ago. Despite the beauty of what they were filming, all of the crew felt relief upon exiting. The way looking at light from millions- and billions- year-old stars evokes a sublime rapture of infinite space, appreciation of art made by incredibly distant ancestors who clearly were just like us—with our same talents and abilities and imaginations—evokes the sublime vertigo of history. The mind fills that vertigo with ghosts.

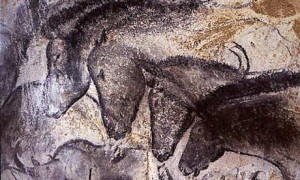

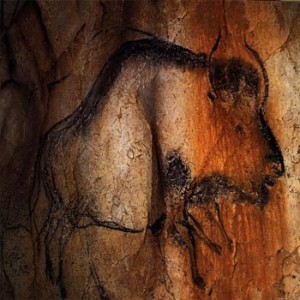

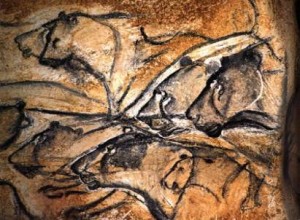

The people who first ventured into the bowels of Chauvet cave with flickering torches to create those animal images clearly felt a profound connection with the natural world and affinity with its creatures. As with most “premodern” cultures, they probably believed in the ability of humans to transform into animals and vice versa. The only possibly “human” representation in the cave is what appears to be the lower body of a woman (resembling the various “Venus” figurines uncovered throughout Paleolithic Europe) and the upper body of a bull. But that image is the single exception—every other image in the cave is of an animal—horses, lions, rhinoceri, mammoths, aurochs, even a butterfly. What did those animals galloping across the walls and out of its recesses represent?

The people who first ventured into the bowels of Chauvet cave with flickering torches to create those animal images clearly felt a profound connection with the natural world and affinity with its creatures. As with most “premodern” cultures, they probably believed in the ability of humans to transform into animals and vice versa. The only possibly “human” representation in the cave is what appears to be the lower body of a woman (resembling the various “Venus” figurines uncovered throughout Paleolithic Europe) and the upper body of a bull. But that image is the single exception—every other image in the cave is of an animal—horses, lions, rhinoceri, mammoths, aurochs, even a butterfly. What did those animals galloping across the walls and out of its recesses represent?

Herzog suggests that the paintings in Chauvet are a sort of “proto-cinema.” The metaphor is clearly more than apt. Not only do the animal figures seem to move under shifting light such as would have been provided by torches (or, in the filmmakers’ case, the few safe cold film lights they could bring with them into the cave), but some of the animals are “multilegged” in what is evidently a deliberate attempt to depict motion.

The illusion of movement depends on a prior, more fundamental illusion, though: the illusion of stasis. The cave was as much a camera obscura as it was a cinema. So I’d add to Herzog’s metaphor and suggest that this Paleolithic cinema was not just a theater but also a philosophical tool—and its animals, object lessons—for examining permanence versus impermanence, the mystery of Time.

The illusion of movement depends on a prior, more fundamental illusion, though: the illusion of stasis. The cave was as much a camera obscura as it was a cinema. So I’d add to Herzog’s metaphor and suggest that this Paleolithic cinema was not just a theater but also a philosophical tool—and its animals, object lessons—for examining permanence versus impermanence, the mystery of Time.

The arrested image is always dazzling and awe-inspiring for people who haven’t seen it before or who don’t see it everyday. In the 19th Century, people reacted to the first Daguerrotypes with surprise and delight. Viewers in the Renaissance reacted the same way to realistic pictures painted with the newly discovered techniques for showing space in perspective. We can readily imagine the mixture of joy, astonishment, and slight unease that a small Paleolithic community would have felt when their brilliant and eccentric cousin led them into a dark, sort of scary cave by torchlight to gaze on what he had been busy creating there on the walls. (“So this is what cousin White Bear has been up to!”)

The best indication that the above reactions were part of the intended reaction of the Chauvet images is that the latter are specifically and entirely (with the part-exception of the Venus-bull) of animals—the things in the painters’ world that were most constantly in motion. No vegetable life was depicted, no people (who have the power to stand still), and no natural or celestial features (the sun, moon, and stars, move only slowly). And this idea of stasis manifests itself on two levels. Amid the growth and motion, birth and death, of everything in those people’s environment, and of everything that they created, the paintings themselves were permanent, and this must have been a large part of their appeal and mystery. The world outside changed but in the depths of the cave was a sanctuary where things stayed the same, where Time stopped.

(In creating something permanent, the painters outdid themselves: The interior of the cave has changed “geologically” over the 32,000 years since the paintings were made—dripping mineral-rich water has sculpted the interior with stalagmites, stalactites, sparkling ribbon-like formations—but the images remain unchanged. Just try and wrap your head around art that has survived that long!)

But in this sanctuary of permanence, those fixed images, as Herzog notes, could be reanimated under flickering torchlight. Was this proto-cinema art for art’s sake—purely for aesthetic enjoyment or dazzlement—or did these still/moving images have, as archaeologists are always quick to say, some kind of ‘ritual function’? When you look at a Renaissance painting of the Virgin, it’s impossible to separate aesthetic enjoyment from religious sentiment—and certainly every individual viewer brings his/her own unique mix of these to the experience—so there’s probably no point in trying to make a definitive answer.

But in this sanctuary of permanence, those fixed images, as Herzog notes, could be reanimated under flickering torchlight. Was this proto-cinema art for art’s sake—purely for aesthetic enjoyment or dazzlement—or did these still/moving images have, as archaeologists are always quick to say, some kind of ‘ritual function’? When you look at a Renaissance painting of the Virgin, it’s impossible to separate aesthetic enjoyment from religious sentiment—and certainly every individual viewer brings his/her own unique mix of these to the experience—so there’s probably no point in trying to make a definitive answer.

But maybe “religious” isn’t the best term—nor “aesthetic.” I think that if there is some content or purpose of the Chauvet images—beyond just “pretty pictures”—that it is philosophical. I don’t think it is coincidence that these cave images seem designed to walk a tightrope between stasis and motion and that the earliest philosophies of which we have written record are devoted precisely to understanding that very dichotomy, suggesting a continuity with prehistoric thought.

The sixth-century BC Chinese philosopher Lao Tze wrote of the flow of things, or the Tao. In fifth-century BC Greece, Heraclitus compared the constant flow of Time to a river; he is most famous for his aphorism that you can’t step in the same river twice. His main metaphor for the constant energy and motion of things, however, was “fire.” It’s tempting to link this philosophical and primordial fire to the firelight cast by Paleolithic torches on cavern walls, providing the illusion of motion to the creatures painted there.

Famously in opposition to Heraclitus was Parmenides (same period), who tried to convince his students that motion is an illusion, that the reality behind the appearances is stasis. His position would later be upheld and “proved” through the famous thought experiments of Zeno—for instance the arrow that, once shot, has to pass halfway to its target, but first halfway to halfway, and first halfway to halfway to halfway, and so on—so that in fact, it can never even start on its path let alone ever get to the end.

The notion that all movement is an illusion might seem silly, but consider memory, which despite the apparent flux of experience seems to hold snapshots, to preserve experience in amber. Art is a reflection of memory and depends on it. Part of what is so astonishing about the paintings in Chauvet is how incredibly realistic, lifelike they are despite the fact that they cannot have been painted from life, only from the artist’s memory. I assume that cave artists of the caliber represented in Chauvet would have to have honed their skills outside in the light—I suppose with a stick in dirt when watching their subjects up close, perhaps over many years.

It takes art to remove us from what we take for granted and show it to us in a new way, as a mystery. That separation and return can provide the sublime rapture that occurs when we push our thoughts to infinities. Time has always been one of the fundamental mysteries, because humans are not cognitively capable of understanding it. I can’t help but think that the awe of viewers of these painted bison, horses, rhinoceroses, mammoths, and lions, or even just the awe of the artist, arose from amazement at Time itself. And in a different way and for different reasons, it’s Time that is amazing about Chauvet cave, and Herzog’s film.

The filmmaker discusses his documentary here.)

***

Incredibly detailed and well considered article Eric! My efforts pale in comparison.