The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

NASA Acknowledges WTFs Near Space Shuttle

Four mysterious objects were detected and filmed near the space shuttle Atlantis, and uncharacteristically NASA acknowledged this encounter — and that such UFOs are witnessed frequently on shuttle missions. See the Fox news report here:

A report on another UFO sighting during Atlantis’s last mission is here:

Check it out.

***

The Madness of White Bear — Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (pt. 3)

The various tricks artists and scientists through history have discovered for seemingly halting the motion of things—what Renaissance alchemists called “fixing the volatile”—and then reanimating the fixed under their own power have always seemed godlike; and the aspiration to exercise this power has always seemed arrogant or even blasphemous to some. We can only speculate, but it is worth asking whether some of White Bear’s kin (see previous post on Werner Herzog’s film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams) were not so supportive of his work.

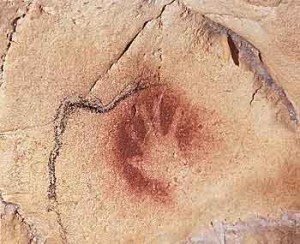

Consider: The walls of Chauvet Cave are not layered with imagery and symbols in the manner of a modern urban canvas such as a freeway underpass. Graffiti is as old as civilization, but in Chauvet Cave there is none of that exuberant transformation of blank surface into picture. There were only a small handful of artists who left their images in the cave over the many, many millennia that humans could have visited and used it, and only some sections of wall have images. This must make us wonder how important or central figurative pictures actually were to the culture of these people.

Consider: The walls of Chauvet Cave are not layered with imagery and symbols in the manner of a modern urban canvas such as a freeway underpass. Graffiti is as old as civilization, but in Chauvet Cave there is none of that exuberant transformation of blank surface into picture. There were only a small handful of artists who left their images in the cave over the many, many millennia that humans could have visited and used it, and only some sections of wall have images. This must make us wonder how important or central figurative pictures actually were to the culture of these people.

The answer could be that the inclination and the genius to create images may have been relatively rare, the product of a very unusual sort of person who may have been regarded with as much distrust or suspicion as admiration by his (or her) fellows. Art, even religious art, always has its detractors.

I am purely speculating, but could these Paleolithic melancholics, these cave Michelangelos living under the sign of Saturn, have represented a departure from the philosophy of the dark that governed the prevailing shamanic culture? Could White Bear and his fellow artists, scattered in time, have essentially misused the cave as a canvas for their madness, blasphemously bringing light into what was supposed to remain in perpetual night?

I am purely speculating, but could these Paleolithic melancholics, these cave Michelangelos living under the sign of Saturn, have represented a departure from the philosophy of the dark that governed the prevailing shamanic culture? Could White Bear and his fellow artists, scattered in time, have essentially misused the cave as a canvas for their madness, blasphemously bringing light into what was supposed to remain in perpetual night?

***

WTFology

Does anybody else think that UFO is too sterile a term? That it fails to capture the emotion behind our quest, the astonishment that drives a witness of something “unidentified” to seek answers?

I’ve decided to, as much as possible, replace the term UFO with WTF. Because that really gets it better, don’t you think? “WTF was that?” “I don’t know WTF it was, but it was moving fast, and then just disappeared!”

“Look dad, it’s a WTF!!”

Changing the name of Ufology to WTFology is a long-overdue step. Who’s with me?

***

Hermetic Astronomy

In Fortean Times there is a new, excellent article on the hermetic context of Renaissance astronomy and Galileo’s famous trial.

The rediscovery of ancient hermetic philosophy during the Renaissance was the most important influence on intellectuals of the period–from Copernicus to Shakespeare–yet few people nowadays are aware of it. As the authors Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince write, “the fact is that the Renaissance is impossible to comprehend without the Hermetic tradition. It’s like trying to write a history of the 20th century while ignoring Communism, on the logic that because it failed as an ideology, it could never have been really important.”

Among other things, the article provides a good background on my personal hero Giordano Bruno, a master of the Art of Memory and one of the first to claim that the universe was infinite and full of inhabited worlds.

***

Slaying the Minotaur — Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (Part 2)

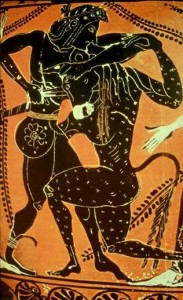

For shamanic religions and the cultures that adhere to them, mystery is higher than knowledge. The irrational higher than the rational. Unknowing higher than knowing. (Is there even a concept of “knowing”? Is “knowing” an idea that has only arisen in after writing??) Paleolithic people, such as those who left their mark in Chauvet Cave 32,000 years ago (see Werner Herzog’s amazing new documentary), undoubtedly believed, as modern shamans do, in ready passage to other worlds, and in the ability of humans to become animals (and vice versa). They accomplished these feats via drugs and drumming and dreams and, probably, via the sensory deprivation provided by caves.

Vestiges of such practices are found throughout the shamanic religions that have survived into our own times. And they were well active in Ancient Greece, the earliest European civilization of which we have much written record. The mystery cults of Dionysus and other deities probably represent vestiges of prehistoric religions. Caves were viewed as the sanctums of gods, and venturing into the dark was a rite and a means of access to the other world.

But somewhere along the line, a profound shift happened in Europeans’ beliefs about the dark. We have long since stopped venturing into the dark for religious communion. Civilized humans have long since ceased to find little but fright, scientific curiosity, and for some, physical adventure in subterranean space. Plato, perhaps the first fully “modern” thinker, famously viewed the cave as a prison of ignorance, not a church. In his metaphor, the cave was a place were people were enchained, watching shadows of puppets projected by a light on a wall (an image uncannily similar to a movie theater—see previous post), and from which they had to be liberated and led out into the light…

But somewhere along the line, a profound shift happened in Europeans’ beliefs about the dark. We have long since stopped venturing into the dark for religious communion. Civilized humans have long since ceased to find little but fright, scientific curiosity, and for some, physical adventure in subterranean space. Plato, perhaps the first fully “modern” thinker, famously viewed the cave as a prison of ignorance, not a church. In his metaphor, the cave was a place were people were enchained, watching shadows of puppets projected by a light on a wall (an image uncannily similar to a movie theater—see previous post), and from which they had to be liberated and led out into the light…

Judeo-Christianity inherited the preference for light and reason over mystery. Consider the Medieval cathedral. It is dark, but it is dark the way a camera is dark: It is a space designed to let light in, via stained-glass windows whose secret formulas died with the alchemists of the period. A cathedral thus reveals the light in a new way. In Eastern religions, “enlightenment” happened via practices of meditation, similar to prayer, not via descent into caves.

Despite our tendency to view the organized religions familiar to us as “irrational” enemies of the scientific worldview, they were intended to enlighten, not obscure or distort reality. Thus they really go hand in hand with philosophy and science. Science could not have arisen in any other but the matrix of Christianity, Islam, and the other religions of enlightenment. (Modern scientific antagonists of religion would do well to bear this in mind.)

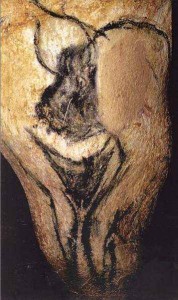

In this regard—the changing meaning of and attitude toward the dark—I wonder if it is significant that the sole apparently “mythological” and (semi-)human representation found in Chauvet Cave is a being with the lower half of a “Venus” and the upper body of a bull—painted ingeniously on a stalactite. Where else in our cultural memory does a half-human, half-bull creature appear? Obviously, in the great Greek myth of the labyrinth of Crete, and the Minotaur inhabiting it. The labyrinth in this story is widely thought to have been a cave, or symbolic of the cave. Could the bull-man be an ancient—incredibly ancient—symbol of something like the “spirit” of caves, or of the dark, that survived into Greek times?

In this regard—the changing meaning of and attitude toward the dark—I wonder if it is significant that the sole apparently “mythological” and (semi-)human representation found in Chauvet Cave is a being with the lower half of a “Venus” and the upper body of a bull—painted ingeniously on a stalactite. Where else in our cultural memory does a half-human, half-bull creature appear? Obviously, in the great Greek myth of the labyrinth of Crete, and the Minotaur inhabiting it. The labyrinth in this story is widely thought to have been a cave, or symbolic of the cave. Could the bull-man be an ancient—incredibly ancient—symbol of something like the “spirit” of caves, or of the dark, that survived into Greek times?

Myths were never meant to be taken literally, and typically they weren’t. The ancients weren’t as credulous as we tend to think. Myths are stories that symbolically encode memories of great events and social, political, economic, and religious transitions—they are the form taken by oral history, the cultural memory of a people. For example, the legend of St. Patrick expelling all the snakes from Ireland symbolically encodes the memory of the banishing of Celtic pagan religion by the arrival of Christianity. (Snakes have always been symbolic of old superstitious cults. The serpent in Eden represented, for the Hebrews, the false, primitive, evil, sacrificial cults that surrounded them in the Levant.)

I cannot help but wonder whether the story of Theseus slaying the Minotaur in the labyrinth of Crete could represent a cultural memory not unlike the story of St. Patrick: A symbolic encoding of the banishment of old mystery cults in favor of a newer, more Platonic view of the universe as something to be illuminated—the first inklings of a scientific worldview, the regime of logic and reason that even to this day is represented by Ariadne’s thread—a way out of the cave.

I cannot help but wonder whether the story of Theseus slaying the Minotaur in the labyrinth of Crete could represent a cultural memory not unlike the story of St. Patrick: A symbolic encoding of the banishment of old mystery cults in favor of a newer, more Platonic view of the universe as something to be illuminated—the first inklings of a scientific worldview, the regime of logic and reason that even to this day is represented by Ariadne’s thread—a way out of the cave.

I’d welcome any response to this idea from experts in Greek mythology: What is the significance of the bull, and the bull-man? Is the Minotaur a cthonic symbol of darkness and mystery, one that could have its roots in a dim Paleolithic past?

***

Cave of Forgotten Dreams

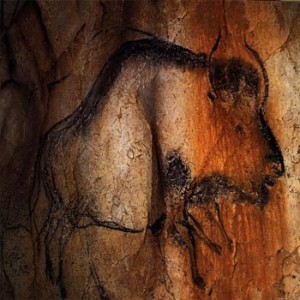

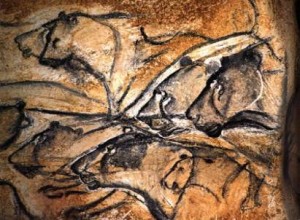

The thing about the sublime as an aesthetic (or religious) emotion is that you can only take it in small doses before it turns into unease and even fear. At one point in Werner Herzog’s new, amazing documentary about the astonishingly realistic Paleolithic paintings in Chauvet Cave in France, the filmmaker notes that he and his film crew—as well as those who had first discovered and explored the cave—experienced an uncomfortable and uncanny sense of being watched by those who had painted the wild animals on its contoured walls some 32,000 years ago. Despite the beauty of what they were filming, all of the crew felt relief upon exiting. The way looking at light from millions- and billions- year-old stars evokes a sublime rapture of infinite space, appreciation of art made by incredibly distant ancestors who clearly were just like us—with our same talents and abilities and imaginations—evokes the sublime vertigo of history. The mind fills that vertigo with ghosts.

The people who first ventured into the bowels of Chauvet cave with flickering torches to create those animal images clearly felt a profound connection with the natural world and affinity with its creatures. As with most “premodern” cultures, they probably believed in the ability of humans to transform into animals and vice versa. The only possibly “human” representation in the cave is what appears to be the lower body of a woman (resembling the various “Venus” figurines uncovered throughout Paleolithic Europe) and the upper body of a bull. But that image is the single exception—every other image in the cave is of an animal—horses, lions, rhinoceri, mammoths, aurochs, even a butterfly. What did those animals galloping across the walls and out of its recesses represent?

The people who first ventured into the bowels of Chauvet cave with flickering torches to create those animal images clearly felt a profound connection with the natural world and affinity with its creatures. As with most “premodern” cultures, they probably believed in the ability of humans to transform into animals and vice versa. The only possibly “human” representation in the cave is what appears to be the lower body of a woman (resembling the various “Venus” figurines uncovered throughout Paleolithic Europe) and the upper body of a bull. But that image is the single exception—every other image in the cave is of an animal—horses, lions, rhinoceri, mammoths, aurochs, even a butterfly. What did those animals galloping across the walls and out of its recesses represent?

Herzog suggests that the paintings in Chauvet are a sort of “proto-cinema.” The metaphor is clearly more than apt. Not only do the animal figures seem to move under shifting light such as would have been provided by torches (or, in the filmmakers’ case, the few safe cold film lights they could bring with them into the cave), but some of the animals are “multilegged” in what is evidently a deliberate attempt to depict motion.

The illusion of movement depends on a prior, more fundamental illusion, though: the illusion of stasis. The cave was as much a camera obscura as it was a cinema. So I’d add to Herzog’s metaphor and suggest that this Paleolithic cinema was not just a theater but also a philosophical tool—and its animals, object lessons—for examining permanence versus impermanence, the mystery of Time.

The illusion of movement depends on a prior, more fundamental illusion, though: the illusion of stasis. The cave was as much a camera obscura as it was a cinema. So I’d add to Herzog’s metaphor and suggest that this Paleolithic cinema was not just a theater but also a philosophical tool—and its animals, object lessons—for examining permanence versus impermanence, the mystery of Time.

The arrested image is always dazzling and awe-inspiring for people who haven’t seen it before or who don’t see it everyday. In the 19th Century, people reacted to the first Daguerrotypes with surprise and delight. Viewers in the Renaissance reacted the same way to realistic pictures painted with the newly discovered techniques for showing space in perspective. We can readily imagine the mixture of joy, astonishment, and slight unease that a small Paleolithic community would have felt when their brilliant and eccentric cousin led them into a dark, sort of scary cave by torchlight to gaze on what he had been busy creating there on the walls. (“So this is what cousin White Bear has been up to!”)

The best indication that the above reactions were part of the intended reaction of the Chauvet images is that the latter are specifically and entirely (with the part-exception of the Venus-bull) of animals—the things in the painters’ world that were most constantly in motion. No vegetable life was depicted, no people (who have the power to stand still), and no natural or celestial features (the sun, moon, and stars, move only slowly). And this idea of stasis manifests itself on two levels. Amid the growth and motion, birth and death, of everything in those people’s environment, and of everything that they created, the paintings themselves were permanent, and this must have been a large part of their appeal and mystery. The world outside changed but in the depths of the cave was a sanctuary where things stayed the same, where Time stopped.

(In creating something permanent, the painters outdid themselves: The interior of the cave has changed “geologically” over the 32,000 years since the paintings were made—dripping mineral-rich water has sculpted the interior with stalagmites, stalactites, sparkling ribbon-like formations—but the images remain unchanged. Just try and wrap your head around art that has survived that long!)

But in this sanctuary of permanence, those fixed images, as Herzog notes, could be reanimated under flickering torchlight. Was this proto-cinema art for art’s sake—purely for aesthetic enjoyment or dazzlement—or did these still/moving images have, as archaeologists are always quick to say, some kind of ‘ritual function’? When you look at a Renaissance painting of the Virgin, it’s impossible to separate aesthetic enjoyment from religious sentiment—and certainly every individual viewer brings his/her own unique mix of these to the experience—so there’s probably no point in trying to make a definitive answer.

But in this sanctuary of permanence, those fixed images, as Herzog notes, could be reanimated under flickering torchlight. Was this proto-cinema art for art’s sake—purely for aesthetic enjoyment or dazzlement—or did these still/moving images have, as archaeologists are always quick to say, some kind of ‘ritual function’? When you look at a Renaissance painting of the Virgin, it’s impossible to separate aesthetic enjoyment from religious sentiment—and certainly every individual viewer brings his/her own unique mix of these to the experience—so there’s probably no point in trying to make a definitive answer.

But maybe “religious” isn’t the best term—nor “aesthetic.” I think that if there is some content or purpose of the Chauvet images—beyond just “pretty pictures”—that it is philosophical. I don’t think it is coincidence that these cave images seem designed to walk a tightrope between stasis and motion and that the earliest philosophies of which we have written record are devoted precisely to understanding that very dichotomy, suggesting a continuity with prehistoric thought.

The sixth-century BC Chinese philosopher Lao Tze wrote of the flow of things, or the Tao. In fifth-century BC Greece, Heraclitus compared the constant flow of Time to a river; he is most famous for his aphorism that you can’t step in the same river twice. His main metaphor for the constant energy and motion of things, however, was “fire.” It’s tempting to link this philosophical and primordial fire to the firelight cast by Paleolithic torches on cavern walls, providing the illusion of motion to the creatures painted there.

Famously in opposition to Heraclitus was Parmenides (same period), who tried to convince his students that motion is an illusion, that the reality behind the appearances is stasis. His position would later be upheld and “proved” through the famous thought experiments of Zeno—for instance the arrow that, once shot, has to pass halfway to its target, but first halfway to halfway, and first halfway to halfway to halfway, and so on—so that in fact, it can never even start on its path let alone ever get to the end.

The notion that all movement is an illusion might seem silly, but consider memory, which despite the apparent flux of experience seems to hold snapshots, to preserve experience in amber. Art is a reflection of memory and depends on it. Part of what is so astonishing about the paintings in Chauvet is how incredibly realistic, lifelike they are despite the fact that they cannot have been painted from life, only from the artist’s memory. I assume that cave artists of the caliber represented in Chauvet would have to have honed their skills outside in the light—I suppose with a stick in dirt when watching their subjects up close, perhaps over many years.

It takes art to remove us from what we take for granted and show it to us in a new way, as a mystery. That separation and return can provide the sublime rapture that occurs when we push our thoughts to infinities. Time has always been one of the fundamental mysteries, because humans are not cognitively capable of understanding it. I can’t help but think that the awe of viewers of these painted bison, horses, rhinoceroses, mammoths, and lions, or even just the awe of the artist, arose from amazement at Time itself. And in a different way and for different reasons, it’s Time that is amazing about Chauvet cave, and Herzog’s film.

The filmmaker discusses his documentary here.)

***

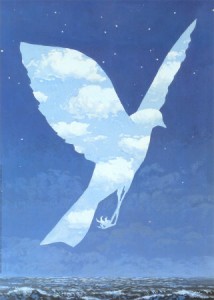

UFOs and the Surreal

Lately I’m interested in art as a window to thinking (visually, narratively) about the unknowable, for example surrealist depictions of posthumanity. Now, over on the great blog The Other Side of Truth, Paul Kimball has written a thought-provoking post on realism versus surrealism as modes of thinking about nonhuman intelligences.

… The problem is that with UFOs in particular, and non-human intelligence in general, we don’t know what is happening. All that we can do is guess… theorize… speculate… and imagine…

Which is why we should be looking to the surrealists, and the abstract artists, and anyone who has offered a view of the world, and of reality, that is open to myriad interpretations, as the artistic model for understanding any interaction we may have with a non-human intelligence. …

Check it out!

The Immensity of Things

Speaking of films that attempt to show the bigness of the universe, a new, anatomically accurate (that is, from actual star mapping) video by the American Museum of Natural History is truly sublime:

***

War of the Worlds One

Few people are aware that many of the best-attested, best-studied, and most astonishing UFO encounters have actually involved military confrontations. Encounters between air force jets and UFOs have occurred throughout the world, including Great Britain, Iran, Chile, Belgium, and the U.S. Many of these are described in detail in a couple of excellent recent books, Leslie Kean’s UFOs: Generals, Pilots, and Government Officials Go on the Record, and John B. Alexander’s UFOs: Myths, Conspiracies, and Realities.

But the first military confrontation with a UFO in modern history occurred on February 25, 1942, over Los Angeles. The real-life “Battle: LA” began about 3AM, when a huge object glided south toward the city from the Northwest. Being just after Pearl Harbor, this was naturally assumed to be some kind of Japanese airship, and the city was blacked out—later all of Southern California from the San Fernando Valley to the Mexican border was blacked out. As it drifted over the city and hovered there, warning sirens blared and anti-aircraft guns, designed to defend the vital aircraft and shipbuilding facilities beneath, began an initial barrage that lasted 20 to 30 minutes. The object then moved south to Long Beach and down the coast, still tracked by searchlights. Then it returned to LA and a second barrage began.

But the first military confrontation with a UFO in modern history occurred on February 25, 1942, over Los Angeles. The real-life “Battle: LA” began about 3AM, when a huge object glided south toward the city from the Northwest. Being just after Pearl Harbor, this was naturally assumed to be some kind of Japanese airship, and the city was blacked out—later all of Southern California from the San Fernando Valley to the Mexican border was blacked out. As it drifted over the city and hovered there, warning sirens blared and anti-aircraft guns, designed to defend the vital aircraft and shipbuilding facilities beneath, began an initial barrage that lasted 20 to 30 minutes. The object then moved south to Long Beach and down the coast, still tracked by searchlights. Then it returned to LA and a second barrage began.

That night, over 1,400 shells were fired at the UFO, but it was impervious. The event was caught on film and in photographs, and it is an eerie sight: What appears to be a large oval object with a dome on top (very like a classic flying saucer), hard to see in the glare of numerous floodlights shining on it from all sides, is peppered continuously by bright blasts from anti-aircraft fire (the film is below). Eyewitnesses attested that there were several direct hits, but they clearly had no effect. Army fighter planes also attacked the object (these accounted for other “sightings” of lights in formation, which has always caused some confusion in the accounts), but their guns, too, had no effect on the object, and the planes were forced to turn away. Witnesses described the scene as being like the Fourth of July, only louder, and that the object itself was beautiful, like a magic lantern.

The air raid warden for the area, a woman named “Katie,” is one of the many who described what they saw in newspaper articles:

“It was huge! It was just enormous! And it was practically right over my house. I had never seen anything like it in my life!” she said. “It was just hovering there in the sky and hardly moving at all. It was a lovely pale orange and about the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen. I could see it perfectly because it was very close. It was big!”

Several people on the ground were killed during the one-sided “battle,” by falling shrapnel, in car accidents (distracted drivers), and by heart attacks from stress.

The possibility that the object was a blimp can largely be ruled out. It seems highly improbable that a blimp could withstand such a barrage, both from the ground and the air, for one thing. And it is known that the Japanese had already given up on the possibility of using blimps in warfare, due to the flammability of the gasses.

Bruce Maccabee has just posted an interesting photographic analysis of the iconic photo of the event (above), which appeared on the front page of the Los Angeles Times on the morning of the 26th. Without knowing the exact location of the spotlights or the height of the object, there is no way to make a precise calculation of the object’s size. However, it would be nearly as big as the diameter of the illuminated area at the convergence of the lights in this photo, as the beams by and large do not continue past it. One estimate of the object’s altitude is 8,000 feet; if the angle of the spotlight beam from the right was 30 degrees, the object would have been roughly 330 feet in diameter. Whatever the exact measurements, the thing was, as the witnesses said, huge.

It’s an interesting bit of analysis. Check it out. Maccabee also reprints a number of news stories about this amazing event, which was quite possibly the first war of the worlds.

Here’s a video with the original CBS News report of the event. The footage is very cool:

…

Ebert on the Universe

One day last week Roger Ebert turned is mind from film to contemplate the immensity of things:

… The universe is too large for me to comprehend how large that really might be. I’ve seen those animations where Earth shrinks to a pin point, and then the sun shrinks to a pin point, and then the Milky Way shrinks to a pin point. The whole map might as well shrink to a pin point, along with the horse it rode on.

… The universe is too large for me to comprehend how large that really might be. I’ve seen those animations where Earth shrinks to a pin point, and then the sun shrinks to a pin point, and then the Milky Way shrinks to a pin point. The whole map might as well shrink to a pin point, along with the horse it rode on.

None of this immensity is affected by what I think about it. It doesn’t depend on being thought about. If it is true that our galaxy alone might contain 30 to 80 million earth-like planets, and if every one of them were occupied by sentient beings, it doesn’t depend on what they’re thinking, either. It all simply exists. …

Read his piece, “The Quintessence of Dust.”

And while you’re at it, watch the the original animation of the immensity of things, Charles and Ray Eames’ wonderful short film, Powers of Ten:

…