The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

Time’s Taboos: Dirty Thoughts on Systems, Syntropy, and Psi

Classical physics, with its totally determinative, forward-in-time, billiard-ball causation, requires sweeping anomalies like psi under the rug, not to mention resigning ourselves to an absence of higher meaning and direction in the universe. Even the local islands of order allowed within the framework of dynamical systems theory that emerged in the middle of the last century with the work of Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Ilya Prigogine, and many others seem (to some) like disappointing consolation prizes in a universe still largely governed by the second law of thermodynamics. Thus in an effort to bridge science and spirituality and transcend bleak mechanistic materialism, a lot of anti-materialist writers are now tweaking thermodynamics in ways that make time appear more symmetrical, the universe less disorderly, and consciousness more central.

The expansive, dissipative past, born in a primordial explosion, seems to demand a receptive orderly destiny to cozily balance things, lest it all end in chaos.

An interesting recent example is the work of Ulisse Di Corpo and Antonella Vannini, who have resurrected mathematician Luigi Fantappie’s mid-20th-century concept of “syntropy,” a postulated countervailing principle to entropy, drawing systems toward complexity, coherence, and order.

Syntropy is retrocausal: Future nodes of convergence and harmony, or “attractors,” exert a pull on the past, according to Di Corpo and Vannini. On the molecular level, special properties of hydrogen bonds (the “hydrogen bridge” discovered by Wolfgang Pauli) make water a uniquely syntropic medium, capable of organizing itself and serving as the basis for the emergence of complex, anti-entropic biological systems out of the entropic, prebiological matrix. In humans and other sentient organisms, emotion acts as a signal current from future attractors; love is a signal of being on a harmonious, life-conducive path, whereas anxiety signals deviation from it. (Thought, by the same token, reflects signals from the past, based on learning and experience.) In this view, as we move toward the future state of order, information is increased—or at least, it does not lose ground in the information/entropy see-saw.

The authors draw on a wide range of research, from quantum mechanics to systems theory to findings in parapsychology, to support their argument. They point for instance to anomalies that seem to indicate consciousness’s power to reverse or inhibit entropy. Robert Jahn and Brenda Dunne’s famous experiments with random event generators at the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research (PEAR) lab showed that directed attention reduced randomness in the machines; this sort of effect has been found in many different types of experiments in many different laboratories. The authors also invoke Rupert Sheldrake’s arguments about “formative causation”—the notion that there is an extra-genetic template guiding the development of complex organisms and preserving a “memory” of past experiences of a species.

Presaging and hovering over syntropy theory and other ‘complementaristic’ attempts at a more meaning-congenial synthesis are Carl Jung’s theories of synchronicity and archetypes, which were, in their day, also intended to supplement the cold meaningless thermodynamic universe with a sense of meaning, purpose, and direction. Synchronicity, his proposed ‘acausal’ connecting principle, was perhaps what we would now call a retrocausal principle, in which events are, as in syntropy, drawn toward some future coherence. Archetypes, the nodes of this coherence, are much like Plato’s “ideal forms” and Di Corpo and Vannini’s attractors—patterning structures latent within the collective unconscious and giving direction to our lives and fates.

Such ideas appeal to our human love of balance and symmetry: The expansive, dissipative past, born in a primordial explosion, seems to demand a receptive orderly destiny to cozily balance things, lest it all end in chaos. But is that really the case? Is it really impossible to account for complexity and order, explain psychic anomalies, and make a home and a role for consciousness without departing from a traditional systems framework?

Such ideas appeal to our human love of balance and symmetry: The expansive, dissipative past, born in a primordial explosion, seems to demand a receptive orderly destiny to cozily balance things, lest it all end in chaos. But is that really the case? Is it really impossible to account for complexity and order, explain psychic anomalies, and make a home and a role for consciousness without departing from a traditional systems framework?

Balance Within Imbalance

In thinking about systems and complexity, I have always taken inspiration from Eric Jantsch’s breathtaking 1980 summa, The Self-Organizing Universe, which showed how entropy-exporting (or “dissipative”) systems arise and flourish and complexify—and give rise to meaningful order—within the traditional principles of thermodynamics. Dissipative systems generate complex emergent forms, including not only the complex forms of galaxies, animal and plant life, and the brain, but also the regularities of social existence and universal symbolic structures related to our life as humans, including the most profound cultural symbols. I think systems theory, and its more recent offshoots like chaos theory, fractal geometry, and so on, can actually go a long way toward explaining the “balance within imbalance” of the cosmos without invoking new complementary principles.

Some portion of the uncanny regularity we detect in our lives arises from how we unconsciously cast meaning forward and reel it in, responding to our own future potentialities. We may even, without knowing it, be co-creating the systems of the natural world.

For example, orthodox systems theory demands no syntropic attractor to account for the geometrically perfect, chambered shell of a nautilus, and doesn’t even suggest there is a blueprint for it within the mollusc’s DNA. A very specific schedule of protein synthesis and chemical reactions triggered by DNA transcription gives rise to cellular structures, which give rise to further structures, in a kind of recursive cascade of emergent forms of increasing complexity; the adult form of the animal, including the intricate structure and pattern of its shell, is a more or less predictable outcome of its growth and energy exchange with its environment.

What’s more, even mechanisms for ‘Lamarckian’ morphological change over the generations in response to life events and environmental pressures are now being revealed through epigenomics: Changes to the cellular environment alter gene expression, with no need to invoke something like Sheldrake’s morphogenetic fields. The symphony of molecular and cellular processes is mindbogglingly intricate, but there is no reason or need to think that the final completed form of the animal is (retro)causative in some abstract Platonic fashion, or that there is any prototype for the nautilus either ahead in the future or out there in some nonlocal informational ether.

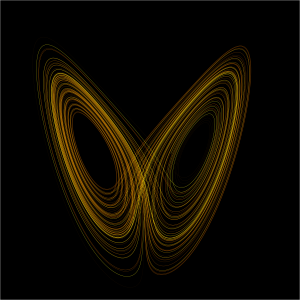

Attractors as chaos theory understands them (versus in syntropy theory) are regularities that emerge as a result of multiple interacting variables that produce feedback loops in the “phase space” of a complex system; these exert a kind of gravitational attraction toward a certain form, like a whirlpool, but there are no blueprints for them. It’s just that the myriad mutually interfering/balancing forces create a regularity of outcomes that looks in hindsight somehow intentional, orderly, and even intelligently designed. It is in this sense that I invoked the concept of attractors in thinking about now misrecognized psi leads to apparent synchronous occurrences in our lives; the difference from Jung’s concept of synchronicity or from Di Corpo and Vannini’s concept of syntropy is that the attractor, the meaningful pattern, is a result, not a cause.

Attractors as chaos theory understands them (versus in syntropy theory) are regularities that emerge as a result of multiple interacting variables that produce feedback loops in the “phase space” of a complex system; these exert a kind of gravitational attraction toward a certain form, like a whirlpool, but there are no blueprints for them. It’s just that the myriad mutually interfering/balancing forces create a regularity of outcomes that looks in hindsight somehow intentional, orderly, and even intelligently designed. It is in this sense that I invoked the concept of attractors in thinking about now misrecognized psi leads to apparent synchronous occurrences in our lives; the difference from Jung’s concept of synchronicity or from Di Corpo and Vannini’s concept of syntropy is that the attractor, the meaningful pattern, is a result, not a cause.

One of Jung’s important insights about religion was that humans personify abstract functions and forces in order to conceptually manipulate them using the familiar metaphors of social interaction (“negotiating” with gods and spirits, for example). Yet his archetypes are themselves sort of artificial personifications—or you might say, mechanizations—of universal human psychic and experiential regularities. The fact that humans everywhere experience certain common themes like heroism and motherhood and the ironic self-undercutting of the “trickster” arguably just reflects the regularities of the mindbogglingly complex systems (within systems within systems…) of human life and mind (including psi, in the case of the trickster), not the machine-like patterning and organizing activity of a preexistent organizing psyche.

I am suggesting that there is no real blueprint for our unfolding “out there” in the collective unconscious, or in the future as understood by syntropy theory. We are radically free agents, and it seems important not to lose sight of this in our attempts to rescue order and meaning (and meaningful anomalies) in the universe. Syntropy and related ideas may be reifying the regular outcomes of systems whose complexity just happens to exceed our human capacity to grasp.

Penetrating Time

Where I strongly agree with both syntropy theory and Jung’s theory of synchronicity, however, is that I think consciousness plays a crucial, decisive role in making our future and shaping reality. Many interpretations of quantum theory insist upon this. And I also strongly agree that the crucial X-factor missing from the standard thermodynamic picture is specifically the future’s ability to affect the past via consciousness (i.e., psi). Systems and attractors, even if they are not determinative, are indeed atemporal, and a future systems theory will need to accommodate consciousness’s ability to penetrate the veil of time.

The boundary we call the “present” may not be a knife edge but a blurry mess, with latent potentials extending well into the past and future.

I have been suggesting on this blog that some portion of the uncanny regularity we detect in our lives arises from how we unconsciously cast meaning forward and reel it in, responding to our own future potentialities. This may include even “we” as observers of other, natural and biological systems (like the slimy systems that produce molluscs and seashells)—and thus we may even, without knowing it, be co-creating the systems of the natural world. In other words, our fate as well as the fate of systems under our purview and observation emerge from a pattern of interaction with the field of future potentialities that we unconsciously detect and respond to, ever misrecognizing (or ‘misunderestimating’) the creative role of consciousness in the whole picture. (I even wonder if some of the effects of globally changing biological systems described by Sheldrake, such as lab animals on one continent learning a new task more readily after conspecifics are trained on that task on another continent, may reflect the role of human consciousness, i.e. the knowledge and intentionality of the experimenters, in shaping those systems.)

Yet, while psi appears to be an interaction with the future (and past), I would argue it is not symmetrical with entropy, and not some kind of natural, born complement, like yin to yang. This may seem like a quibble, but it actually makes a world of difference, because it restores an instability or imbalance—indeed, incoherence—that needs to be there. Noncoherence, the nonidentity of things with themselves—what the Buddhists call “no self” and what Slavoj Žižek calls “parallax”—is essential to the openness and nondeterminism of the universe and the real existence of free will.

Yet, while psi appears to be an interaction with the future (and past), I would argue it is not symmetrical with entropy, and not some kind of natural, born complement, like yin to yang. This may seem like a quibble, but it actually makes a world of difference, because it restores an instability or imbalance—indeed, incoherence—that needs to be there. Noncoherence, the nonidentity of things with themselves—what the Buddhists call “no self” and what Slavoj Žižek calls “parallax”—is essential to the openness and nondeterminism of the universe and the real existence of free will.

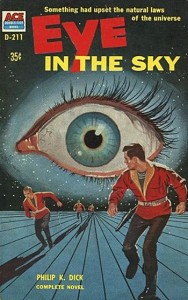

The past is half of time, but its complement is purely virtual or imaginary, and the boundary we call the “present” may not be a knife edge but a blurry mess, with latent potentials extending well into the past and future, insofar as they remain unobserved and unmeasured, and thus opening up a whole realm of PhilDickian effects. If psi is related to the perception of quantum potentials and probabilities, as I have suggested in previous posts, it may arise from precisely this asymmetry in the order of things (i.e., parallax). Both the mind and our culture balk at such an asymmetry, though, as well as at the notion that the past and future can interpenetrate. Despite ostensibly offering a way for the future to affect the past, I think concepts like syntropy and synchronicity also paint a picture of a pristine, family-friendly cosmos in which truly messy asymmetries in the order of things, and taboo possibilities like time travel, are papered over.

The Future Looks Shitty From Here

Part of the problem syntropists have with existing dynamical systems theory is that systems “shit”: They take in energy, convert it to order/information, but ultimately excrete (“dissipate”) chaos. They are not content to find meaning in local islands of order (dissipative systems) so long as there is seemingly a larger gain in disorder across the universe as a whole. Even the most beautiful and perfect systems wallow in a bigger pigsty universe where the shit (chaos) just piles higher and deeper. In a purely classical universe, that shit would indeed ultimately swallow and engulf the whole.

The latent Not Yet in quantum physics is often described as a “smear” of potentials existing in a state of quantum superposition. Thus we should not miss how disgusting the world of unactualized potentiality is.

Quantum physics (at least as I understand it) is not as interested in this classical “future” and “past,” as demarcated neatly on some dimensional timeline, as it is in the distinction between the Actual and the Potential, or what I like to think of as the Is and the Not Yet. At any given point in time, from the standpoint of an observer, the past may be a good-enough proxy for the Is, or what has been “collapsed” through observation, but in fact even the landscape of the Is is permeated by the Not Yet in the form of vast reserves of unobserved and thus uncollapsed potential that remain out of view, just under the skin of the visible universe—like Schrodinger’s cats trapped in the walls. This may help account for various retrocausal effects seen in laboratories, such as the rather mindbending experiments of Helmut Schmidt, where subjects affected a random number generator in the past via their intention; according to Henry Stapp, it may also account for Benjamin Libet’s paradoxical findings that seemed to disprove the existence of conscious will (I’ll return to this in a later post on Stapp’s fascinating work).

That latent Not Yet in quantum physics is often described as a spread-out “smear” of potentials existing in a state of quantum superposition. Thus we should not miss how disgusting the world of unactualized potentiality is: Isn’t that “smear” a little bit like the pigsty future promised by classical thermodynamics? When you think about it, unactualized potentials are the ultimate mess; it is only when consciousness engages in observation that that mess is “cleaned up” so to speak, to become something real and solid and shiny and pristine and definite. Mentally intervening or meddling in the not-yet-actual via psi, though, is basically wallowing in that disgusting gray smear of quantum possibility.

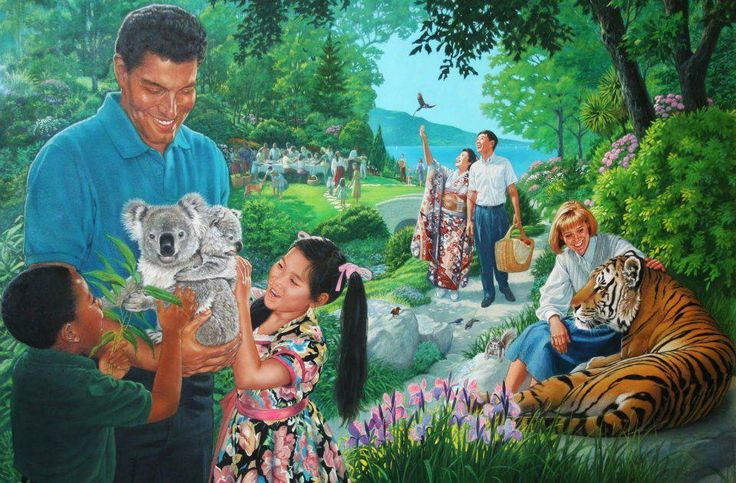

The syntropy model with its future attractors drawing us toward them with love sort of bowdlerizes the disgusting-sounding possibilities latent in quantum physics (and psi), by replacing the indeterminate gray smear with an “already existing future” that looks rather like a scene from a Jehovah’s Witnesses pamphlet: Shiny beautiful glowing perfect people beckoning to you to come join their church picnic. But I think the syntropists (and Platonists, and Jungians) needn’t worry: Consciousness itself is bound to transform the from-here-disordered-looking future into some kind of order and information, even if there’s no way to predict what that order will look like.

The syntropy model with its future attractors drawing us toward them with love sort of bowdlerizes the disgusting-sounding possibilities latent in quantum physics (and psi), by replacing the indeterminate gray smear with an “already existing future” that looks rather like a scene from a Jehovah’s Witnesses pamphlet: Shiny beautiful glowing perfect people beckoning to you to come join their church picnic. But I think the syntropists (and Platonists, and Jungians) needn’t worry: Consciousness itself is bound to transform the from-here-disordered-looking future into some kind of order and information, even if there’s no way to predict what that order will look like.

And we do home in on that future precognitively. But that precognitive engagement with our future potential actually trespasses on taboos even more basic than the scatological: Psi, insofar as it is ‘intercourse’ with the hidden Not Yet under the skin of reality, is basically the temporal equivalent of incest: fundamentally prohibited, and declared “impossible” because we just don’t want to have to form a mental picture of something that is deeply, deeply awkward.

Time and the Oedipus Complex

Even if we are ‘intellectually’ on board with the notion of precognition, some part of us balks at the perversity of a universe that includes information (let alone objects and people) traveling backward in time. The perversity of time travel is, I think, the real meaning of the myth of Oedipus.

A story about a prince taking the place of his own father and marrying his own mother is about the closest the ancient world had to a story about time travel and its paradoxes. Sophocles was Greece’s Phil Dick.

The ancients reckoned the forward, unidirectional, linear flow of time (chronos) through generations—the inevitable, always-forward-moving structure of kinship as well as the forward march of political regimes passed down via offspring. In a sense, kinship and politics were kind of equivalent to the second law of thermodynamics for us, something inexorable and irreversible, moving in a single direction, never flowing backwards, and always basically getting worse (thus always dramatized as tragedy). Thus a story about a prince taking the place of his own father and marrying his own mother is about the closest the ancient world had to a story about time travel and its paradoxes. Sophocles was basically Ancient Greece’s Phil Dick.

That Oedipus was effectively a time traveler has long been part of the esoteric understanding of that myth. Consider the role of the Sphinx, whose riddle Oedipus correctly answers before he becomes King of Thebes. Sphinxes are symbolic guardians of Time. When HG Wells’ Time Traveler (in The Time Machine) visits the distant future, for example, he finds that a great Sphinx structure has been erected more or less on the site of his laboratory. After his machine is confiscated, he must penetrate that structure to find it and return to Victorian England.

That Oedipus was effectively a time traveler has long been part of the esoteric understanding of that myth. Consider the role of the Sphinx, whose riddle Oedipus correctly answers before he becomes King of Thebes. Sphinxes are symbolic guardians of Time. When HG Wells’ Time Traveler (in The Time Machine) visits the distant future, for example, he finds that a great Sphinx structure has been erected more or less on the site of his laboratory. After his machine is confiscated, he must penetrate that structure to find it and return to Victorian England.

The way one defeats time is by reordering it, signaled by the “creature” in the Sphinx’s riddle: What goes on four feet in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three in the evening? Viewers of the play knew the answer was “man,” who first crawls, then walks upright, then moves with the aid of a cane; but the story implied that most “men” don’t get the answer, and this ignorance is their Achilles heel, enabling the Sphinx (/Time) to defeat them. Oedipus was himself the completion of the riddle, in some sense; he walks with a limp, and his name means “swollen foot” (his father Laius and other male ancestors all also had names connoting “lame” or “limping”). Thus Oedipus was the sole (get it, sole?) human who walked upon only one (good) foot—thus completing the quaternity of the Sphinx’s riddle, but further destroying its numerical sequence.

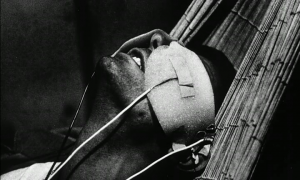

Blindness and Enjoyment

Di Corpo and Vannini argue that emotions, principally love, are the cord drawing us toward future order. If I am right, it may be something more like enjoyment that transcends time and acts as the carrier of information from our future. (Love per se is a special condition in which we experience enjoyment in common with other people—a unique problem at the heart of social existence and a crucial way in which psi guides and directs us toward others to reproduce and form complex social systems.) I have argued, based on a metaphysically broadminded reading of Lacan and Žižek, that enjoyment must in some sense be “nonlocal”; it is through repetition that a symptom acts as a mechanism amplifying the future’s effect on the past and vice versa. Symptoms are atemporal/acausal formations within the sea of enjoyment. Hence the connection between prophecy, neurosis, art, and ritual/repetition.

How many of our dreams tell of future events that might have occurred but didn’t, because we live in an open, nondeterministic universe? Psi may always be visible only in a very narrow band at the edge of our consciousness.

Enjoyment, which “impossibly” connects the future to the past, is thus what turns psi into a psychoanalytic problem: The point is not merely that Oedipus “traveled into the past” by marrying his mother and killing his father; it is that he committed these crimes and enjoyed them, and only belatedly discovered what it was that he had been enjoying. His guilt was not over his actions but over his misrecognized enjoyment. Our ignorance as to our enjoyment (i.e., our blindness to it) allows both the past and future to affect our lives in uncanny and seemingly “impossible” ways like synchronicity.

Oedipus’s self-blinding upon discovering his crime is always seen as a kind of dramatic literalization of his own blindness at not having heeded various prophecies, like those of the blind Tiresias—another character who (psychically, in this case) “travels through time.” It suggests to me a secret connection or even identity between these two figures: They are two sides of the same coin. The past and future cannot affect the present except insofar as we are blind to our true enjoyment; they derive their power (and ability to travel through time and space, their nonlocal “cloaking” from the eyes of Heisenberg) from being unseen and unknowable—at least by the persons they most closely affect. Hence prophets are, at least figuratively, blind; and we are largely blind to psi’s actions (and enjoyment) in our lives.

As I mentioned in my post on Vallee and remote viewing, fundamental philosophical conundrums effectively “hobble” or at least severely restrict psi, including the Platonic inability to know what we don’t know. This as well as other factors, such as the “perverse” fact that penetrating the veil of time involves secret/disavowed enjoyment, may tend to work against individually “knowing the future” in a literal or actionable way.

As I mentioned in my post on Vallee and remote viewing, fundamental philosophical conundrums effectively “hobble” or at least severely restrict psi, including the Platonic inability to know what we don’t know. This as well as other factors, such as the “perverse” fact that penetrating the veil of time involves secret/disavowed enjoyment, may tend to work against individually “knowing the future” in a literal or actionable way.

Ordinarily, the future seeps into our consciousness to the degree that we misinterpret it, and our most vivid foreknowledge is only verified after the fact, in dreams, artworks, and other nonliteral “transmissions” that usually don’t seem very useful in consciously altering our course or changing our destiny. By the same token, when psi does provide premonitions or warnings we heed, the status of those “predictions” as information may evaporate because we have no way to verify them (except in vivid cases like airplane crashes or ocean liner sinkings). How many of our dreams tell of future events that might have occurred but didn’t, because we live in an open, nondeterministic universe? Psi may always be visible only in a very narrow band at the edge of our conscious awareness.

The methods devised at SRI to amplify the psi signal and make it efficacious in the real world involved protocols to work around these types of problems. Remote viewers must be “blind” (in the figurative, experimental sense) to the target, first of all. Thus psi really only works in groups of at least two, preferably three people, who possess different degrees of knowledge about the target or question to which an answer is sought. Also, the rigid formalistic protocol itself works to distract and occupy the conscious mind so that psi information can be received more easily via unconscious channels. And, most importantly, confirmation is necessary, which may be understood as providing the insecure psi mind with rewards (like sardines to condition the behavior of a dolphin) or may be understood as the actual target of remote viewing, if we accept the possibility that it may in fact just be precognizing our own future states of enjoyment/reward. (In his book Limitless Mind, Russell Targ considers feedback a usually essential part of Remote Viewing; although, in considering this question of its necessity, he does cite a few experiments that seem to show successful remote viewing in the absence of feedback.)

From Syntropy to Parallax

So to sum up: Order not only arises provisionally, contingently, within the “doomed” chaotic system described by classical thermodynamics, but also hovers over and lurks within it as consciousness in its constant interaction with unrealized potentiality. Syntropy, like certain other concepts in post-materialist thought, might best be understood as an umbrella term covering various entropy-defeating phenomena in their as-yet mostly unmapped interaction, rather than as as a reified principle or “force” all its own. I’m not sure Di Corpo and Vannini mean to suggest that that syntropy is actually causative, any more than Jung meant to imply that about synchronicity, yet these concepts are susceptible to that interpretation, and certainly Jung’s concept (which suffered from vagueness) has been ‘perverted’ in that way over the years.

Fortunately the unconscious, which has no sense of time, cannot be offended by the outrageous paradoxes and perversions that enable quantum physics—and psi—to work.

Einstein can serve as a warning about the haste to add new principles when we don’t immediately like what we see about reality. He felt that the picture of the universe in disequilibrium that his own theories led to required a new yet-undiscovered principle, so he postulated a “cosmological constant” to make the equations add up in a more intellectually and aesthetically congenial way. There was no evidence for such a thing, and later he regarded this as the biggest blunder in his career (although new theories of dark energy do sort of harken back to it). The physical laws we know about may not be the only ones, and as Sheldrake importantly argues, they may not actually be set in stone; but they still may be able to do the job. Quantum physics seems like it provides what we need, particularly given that it not only allows but actually requires precisely what was missing in the classical universe: a role for consciousness, and the possibility of causal interactions that defy our commonsense understandings of spacetime.

Part of what keeps us from embracing the discomfiting parallax and asymmetry of things is our sense of meaning as a kind of equals sign. “Meaning” in this sense collapses when we replace the Minkowski glass-block universe (where the future already exists) with a state of radical indeterminacy. In lived fact, there is no meaning, just a succession of states within a larger turbulent, looping flow. Those states appear “meaning-like” in hindsight, when we imagine time as flattened and static, but that fiction of meaning is a screen masking the acausal obscenities I described.

Fortunately the unconscious, which has no sense of time, cannot be offended by the outrageous paradoxes and perversions that enable quantum physics—and psi—to work.

Unknown Unknowns: Psi, Association & the Physics of Information

I have always been skeptical of parapsychologists, because their experiments and their theories borrow the standard concepts of space and time dimensions from physics. These concepts seem obsolete to me. They are not appropriate for understanding telepathy, or the moving of objects at a distance, or ghosts, or Melchizedek. I have always been struck also by the fact that energy and information are one and the same thing under two different aspects. Our physics professors teach us this; they they never draw the consequences. —Jacques Vallee

In his 1979 book Messengers of Deception, Jacques Vallee called for a “physics of information” that would enable scientists to think in a more nuanced way about a wide range of paranormal phenomena. Four decades later, it is an idea that is now strongly resonating with many UFO writers. The late Bruce Duensing had been thinking about the equivalence of energy and information on his blog, for example; and lately I see the phrase “physics of information” everywhere I turn. Vallee himself reiterated his call in a TED talk, “A Theory of Everything (Else)” a few years ago (linked below).

In absence of a nice, materialist-sounding theory, the behavior, or character, of psi becomes almost like an interaction with an omniscient intelligence.

What Vallee’s book (and TED talk) left mostly between the lines is that his idea for such a physics arose as much or more from his involvement with psi research in the 1970s as it did from his thinking about UFOs. As a friend and colleague of the CIA-funded researchers and psychics who were revolutionizing the study of psi at SRI, Vallee, whose day job at SRI in the early part of that decade was developing the Arpanet, was in the right place at the right time to cross-fertilize their work with his own wildly outside-the-box thinking. (If there’s anything studying UFOs can do to some people, it is removing the usual barriers to thought and creativity.) Vallee’s contribution to the field of psi was decisive, and his comment about a physics of information directly refers to that contribution.

From the beginnings of psychical research in Frederic Myers’ day up until the early 1970s, psi was commonly (albeit not universally) assumed to work somehow on the model of telegraphic or radio transmission. This metaphor invokes the notion of a sender and receiver, and thus psi was generally thought to be fundamentally a connection between minds—that is, telepathy. The early research at SRI proceeded on this assumption. At SRI, the early protocol in what came to be called “remote viewing” was to use an “outbounder” as a psychic transmitter—that is, a confederate who went to a randomly determined location in the Bay Area while the psychic back at the lab described what they were seeing.

From the beginnings of psychical research in Frederic Myers’ day up until the early 1970s, psi was commonly (albeit not universally) assumed to work somehow on the model of telegraphic or radio transmission. This metaphor invokes the notion of a sender and receiver, and thus psi was generally thought to be fundamentally a connection between minds—that is, telepathy. The early research at SRI proceeded on this assumption. At SRI, the early protocol in what came to be called “remote viewing” was to use an “outbounder” as a psychic transmitter—that is, a confederate who went to a randomly determined location in the Bay Area while the psychic back at the lab described what they were seeing.

The SRI team was at that time struggling with how to make this form of clairvoyance more suitable to real-world intelligence applications, and they were forced to adjust their operating assumptions to a growing realization that it didn’t actually operate by known physical principles, or via anything like telepathy. They could find no electromagnetic force at work and no “inverse square law” that diminished ESP or psychokinesis (PK) over distance, and psi effects seemed to ignore any form of electromagnetic shielding. Another blow to the “telepathy” concept came from New York artist/psychic Ingo Swann, who brought to the team a different model of how psi operated—not as telepathy but as some discarnate part of consciousness leaving the body and seeing things at a distance.

In his own previous work with ESP researchers in New York, Swann had traveled out of body to view concealed objects, and thus his assumption was that a psychic didn’t need another person as a sender of the information; the psychic could theoretically just “go there” and see the target in his/her mind. This worked so long as you knew where you were trying to go psychically; but the protocols at SRI demanded the psychic be blind to what and where the target was. How could the psychic know where to send his or her consciousness, or find the needed information, without something concrete to home in on?

Here is where Vallee, with his experience in the problem of accessing information in the virtual, dimensionless world of a computer database, was able to offer Swann a key piece of insight: thinking of psi information in terms of “addressing.” Vallee thus suggested to Swann using geographic coordinates to designate the target.* Swann saw the logic of this, and (according to Jim Schnabel’s account in his book Remote Viewers) initially waged an uphill battle convincing Hal Puthoff and the other SRI folks to experiment with using coordinates. The tries were a success, and thus “coordinate remote viewing” or CRV was born—the methodology that became the military protocol refined and taught by Swann to the first generation of military remote viewers over the subsequent decade.

Just Say “Target”

The leap initiated by Vallee and Swann should not be underestimated. The logic of using coordinates is really an ‘illogic,’ with any moment’s thought about the problem: Geographic coordinates are a purely human construct with no objective link to places on the globe; they are an arbitrary informational overlay. It is an example, in fact, of the arbitrary connection between words and things that forms the basis of structural linguistics—the signifier bears no necessary connection to the signified; linguistic meaning is a function of how signifiers relate to each other, as in a vast grid system, not how they relate to actual things in the real world. We are thus able to use words grammatically correctly even before we know what they refer to; the way they connect in our minds to actual things depends instead on associative linkages, built up and reinforced across early life (and later) experience (I’ll return to this below).

The notion that the psychic apparatus can seek and find “the right answer” based on an arbitrary signifier is another version of the basic stone of offense that prevents skeptics from accepting psi on principle: Where is the psychic getting their information?

The arbitrariness of map coordinates produces a special conundrum when applied to psi in the way Vallee was suggesting: If given a set of map coordinates, the viewer theoretically and ideally has no idea what those coordinates relate to. It’s like being asked to go get a chapeau if you know no word of French. How, then, does the psychic apparatus “know” to go to the right place? Yet amazingly, and illogically, the SRI researchers found that using coordinates worked just as well as using a human outbounder. Somehow, the psychic apparatus did know where to access the requested information, even though the viewer possessed no conscious knowledge (at least with any precision) of Earth coordinates.

Eventually, given the remote but plausible idea that viewers could make guesses about the target based on having memorized the earth’s geographical coordinates (perhaps through months and years of CRV practice), coordinates were replaced by even more arbitrary symbol or number systems. As Schnabel records, SRI remote viewer Keith Harary at one point exasperatedly said to Puthoff, “Why don’t you just say ‘target’?” Indeed, just saying ’target’ worked as well as coordinates or random numbers. The psychic apparatus still knows where to seek and find the information even with the barest minimum of a signifier designating the information sought. (Consequently, the “C” in CRV eventually came to stand for “controlled” rather than “coordinate,” to reflect that military viewers departed from the coordinate system in favor of even more arbitrary codenames.)

What, then, is the word “target” or an arbitrary codename standing for? If it is simply marking or registering the intent of an assigning officer, it raises the question whether remote viewing still involves, or is even mainly, a form of telepathy—that is, connecting, via that codeword, to the intentions of a distant, unknown person who does know where the target is, rather the same way a psychometrician might handle a cigarette lighter and provide information about its owner. Or, does “target” register or mark something more abstract in the nonlocal psychic database, like “the right answer” or “the correct target”? Does it even serve a purpose, or is it just a kind of empty ritual in the whole process?

What, then, is the word “target” or an arbitrary codename standing for? If it is simply marking or registering the intent of an assigning officer, it raises the question whether remote viewing still involves, or is even mainly, a form of telepathy—that is, connecting, via that codeword, to the intentions of a distant, unknown person who does know where the target is, rather the same way a psychometrician might handle a cigarette lighter and provide information about its owner. Or, does “target” register or mark something more abstract in the nonlocal psychic database, like “the right answer” or “the correct target”? Does it even serve a purpose, or is it just a kind of empty ritual in the whole process?

The notion that the psychic apparatus can seek and find “the right answer” based on an arbitrary signifier is another version of the basic stone of offense that prevents many people, especially hardcore skeptics, from accepting psi on principle: Where is the psychic getting their information? The persistence of the electromagnetic theory, or the concept of an “energy” being transmitted through space, at least held out the possibility that psi had a rational basis that might one day be assimilated within our understanding of physical laws. But the SRI work, in various ways, undid those notions and left psi without any firm footing, even as it resulted in an actual method that could be taught and applied in real-world settings. In absence of a nice, materialist-sounding theory, the behavior, or character, of psi becomes almost like an interaction with an omniscient intelligence.

Traversing Events by Association

So, it is partly this situation and realization—that information is structured in the universe such that it can be accessed through arbitrary symbols—that Vallee meant by a physics of information that would replace our everyday physics of space and time conceived as dimensions. Cartesian coordinates (which he astutely notes are probably conceptual artifacts of graph paper) are inadequate for accessing data on a computer network. Information is scattered randomly and in fragmentary fashion in such systems and must be accessed through addressing schemes and algorithms that home in probabilistically on the required data. Search terms connect to this information associatively.

Synchronicities and remote viewing both share the central mystery of meaning: How can the Universe know our own intentions, thoughts, needs, etc.?

He suggests that the problem of accessing information in psychic space via association is directly related to a more familiar problem experienced even by non-psychics, the meaningful coincidences Jung called “synchronicity.” During the period leading up to Messengers, Vallee experienced a real doozy, which shook his prior assumptions about causality to the core. After seeing the name Melchizedek scrawled on the Paris metro, Vallee learned that the name (Abraham’s teacher in the Old Testament) referred to a UFO group, which turned out to have members even in California, where he was then living. He then devoted a great deal of work to this and other groups and their beliefs about UFO contact. Then, the week when he started compiling his notes on Melchizedek and writing Messengers, he was given a cab ride in LA, and when he later looked at the receipt the driver had given him, it said “Melchizedek.” There was only one person with that surname in the LA phone directory. Unless someone or something was staging an elaborate hoax to screw with him, the odds against that one person driving the cab he happened to hail on an LA street are impossible to calculate but must be astronomical.

Creative work invites small synchronicities, almost to the point where I consider it its own variety of the phenomenon. Even in the course of writing this post, I experienced an intense perfect storm of “research synchronicities” in which previously unread books or previously unseen web pages magically fell open to the exact information I needed and/or took me down some personally significant rabbit hole. Any creative writer or artist knows this experience, and may even come to take these things for granted. However, synchronicities of the scope of Vallee’s Melchizedek are rarer and may be life-altering. Jeffrey Kripal, who visited Vallee’s home while researching a chapter on him for his book Authors of the Impossible, notes that Vallee had built a series of five stained glass windows in his study honoring his life’s passions; one of them depicts the Biblical Melchizedek. (As I suggested in a previous post, honoring our synchronicities has the effect of connecting with the thread of our enjoyment and setting up the expectation of coincidence, which increases their frequency.)

Creative work invites small synchronicities, almost to the point where I consider it its own variety of the phenomenon. Even in the course of writing this post, I experienced an intense perfect storm of “research synchronicities” in which previously unread books or previously unseen web pages magically fell open to the exact information I needed and/or took me down some personally significant rabbit hole. Any creative writer or artist knows this experience, and may even come to take these things for granted. However, synchronicities of the scope of Vallee’s Melchizedek are rarer and may be life-altering. Jeffrey Kripal, who visited Vallee’s home while researching a chapter on him for his book Authors of the Impossible, notes that Vallee had built a series of five stained glass windows in his study honoring his life’s passions; one of them depicts the Biblical Melchizedek. (As I suggested in a previous post, honoring our synchronicities has the effect of connecting with the thread of our enjoyment and setting up the expectation of coincidence, which increases their frequency.)

Synchronicities like Melchizedek and remote viewing within the new nonlocal paradigm of Vallee’s SRI friends both share the central mystery of meaning: How can the Universe know our own intentions, thoughts, needs, etc.? There is something outrageously “godlike” about synchronicity, and the extent to which we are awed (and confused) by such occurrences attests to our unwillingness to leave it all up to God or some higher intelligence.

In Messengers, Vallee gave a fascinating taste of what a physics of information would entail, and how it might link up his various interests:

If there is no time dimension as we usually assume there is, we may be traversing events by association. Modern computers retrieve information associatively. You “evoke” the desired records by using keywords, words of power: you request the intersection of “microwave” and “headache,” and you find twenty articles you never suspected existed. Perhaps I had unconsciously posted such a request on some psychic bulletin board with the keyword “Melchizedek.” If we live in the associative universe of the software scientist rather than the sequential universe of the spacetime physicist, then miracles are no longer irrational events. The philosophy we could derive would be closer to Islamic “Occasionalism” than to the Cartesian or Newtonian universe. And a new theory of information would have to be built. Such a theory might have interesting things to say about communication with the denizens of other physical realities.

The Universe as Dream

Information is only information to a thinking being. Thus there can be no abstract, objective physics of information; rather, such a physics would be a sort of epistemology, the study of knowledge and how we know, and how it inevitably relates to a subjective knower. This inevitably leads to the question of consciousness and its relation to matter (including the brain).

The fact that synchronicities and UFO phenomana so strongly reflect an associative (rather than causal) logic tells us—and early on, told Vallee—that they cannot be regarded solely as matters of objective reality.

The notion that we exist in a nonlocal quantum field of information that fundamentally has no spaciotemporal dimensionality at all is widely accepted in the physics community as well as among today’s psi researchers, and thus is destined to transform the brain sciences and psychology as well (even if the psychologists need to be dragged into the new paradigm kicking and screaming). The physicalist presumption that consciousness arises from brain activity cannot be supported either philosophically or empirically (as any number of writers have lately pointed out). And for the most part, information may not in fact be “stored” in the brain as representations, despite our habit of thinking about it as a memory bank.

Yet, the brain is undeniably central in our embodied experience of being alive, either as a mediator between consciousness and events unfolding in physical reality (for instance as a “receiver,” although that partakes of a metaphor that is becoming increasingly obsolete) or, in Bernardo Kastrup’s terms, as an “image” of the localization of our egoic experience within the larger field of consciousness. Whatever the case, I suspect that a future Quantum Neuroscience may come to understand the brain as a system of finding needed information from the larger nonlocal quantum field—that is, it is an information registration or accession system, like a card catalogue in a library or, just as Vallee anticipated, a search system in a computer network. (Or, it will be seen as the ‘image’ of such a system.)

What occurrences like Melchizedek seem to suggest is that the structure of time and causality as we experience them are dictated by the associative linkages among symbolic information. The universe of potential things to know, potential information, may be “out there” in the nonlocal field, but our brains are the gateway to it, because our neural architecture contains the accessing scheme. The study of dreaming and the ancient punny, associative, and spatially organized “art of memory” provide much insight into how this scheme functions and is created and maintained.

Dreaming is essentially the art of memory operating automatically while we sleep, although it probably also goes on continuously below the level of conscious awareness even during waking hours. I have described this elsewhere as “making new memories” although it would probably be more accurate (following the recent work of Sue Llewellyn) to say “making associative junctions.” Those junctions not only help us access mnemonic information (wherever it actually resides) and, more often, cobble-together good-enough reconstructions of past events with a liberal dosing of schematic “frog DNA” to make it seem and feel complete and accurate. These junctions also keep events in our lives bundled together to preserve an adequately accurate internal chronology. In the absence of an objective temporal yardstick, keeping events that happened together associated with each other is the only way we can preserve a sense of our own biography and, thus, sense of self.

Dreaming is essentially the art of memory operating automatically while we sleep, although it probably also goes on continuously below the level of conscious awareness even during waking hours. I have described this elsewhere as “making new memories” although it would probably be more accurate (following the recent work of Sue Llewellyn) to say “making associative junctions.” Those junctions not only help us access mnemonic information (wherever it actually resides) and, more often, cobble-together good-enough reconstructions of past events with a liberal dosing of schematic “frog DNA” to make it seem and feel complete and accurate. These junctions also keep events in our lives bundled together to preserve an adequately accurate internal chronology. In the absence of an objective temporal yardstick, keeping events that happened together associated with each other is the only way we can preserve a sense of our own biography and, thus, sense of self.

In searching our memories for information, we do precisely what Vallee described: we “traverse events by association.” Those associations operate exactly the way Freud described in his work on dreams: They are often non-logical, governed by root metaphors that are often highly concrete (even superstitiously simple-minded), and operate by puns and various literary devices and tropes—precisely the logic of surrealism, myth, and folklore. And they are situated in distinct spatial environments that are often familiar or related to the environments of our early life and formative years. As I argued in my “Feeding the Psi God” post, precognitive dreaming appears to create associative memory junctions for future experiences in precisely the same way.

The fact that not only synchronicities but also UFO phenomena so strongly reflect precisely such an associative (rather than causal) logic tells us—and early on, told Vallee—that they cannot be regarded solely as matters of objective reality. The psyche of the witness is inextricably entwined with whatever is happening to him/her on an objective level. It could be that technology is interacting with and stimulating their associative neural networks to produce a certain experience; it could be that alien beings or technology somehow navigate a psychic interspace; or it could be that, to make sense of a fundamentally baffling experience, the witness is forced to draw upon deep cultural and personal associations. It could be all of these things. Duensing’s blog, A Transit of Contingencies, is essentially a prolonged, dense, but rewarding meditation on these possibilities. (A recent Radio Mysterioso tribute conversation with Duensing afficionados “Burnt State” and “Red Pill Junkie” is a good, accessible exegesis of Duensing’s ideas.)

Before Vallee, Carl Jung insightfully saw the psychic connection or dimension of UFOs, regarding them as linked in some way to the collective unconscious. The folkloric dimensions of UFO encounters certainly speak to the shared nature of basic cultural symbolism within communities. But the most fundamental symbols in our lives—the most effective “power words” in our associative mental registry—are always those that feel most unique to us, even if we happen to share those symbols with others or, indeed, with the whole human race.

There’s a large body of anthropological research on the way shared symbols become powerfully personal and motivating by linking to our personal psychosexual lives, and it is why Freud remains hugely influential in anthropology (probably the only place in science, anymore, that he is still read), whereas Jung, despite taking such a deep interest in myth, is not. The motivating power of symbols, be they simple arbitrary signifiers like “chapeau” (or “target”) on up to core religious and cosmological motifs, is not automatic and mechanical, emanating from some collective psychic interspace that precedes us, but is highly idiosyncratic and, in the case of religious symbolism, built up through emotionally moving religious (and, I would add, paranormal) experiences in our lives. The unconscious, where our associatively linked symbols are active, is consequently a deeply private, personal place.

This matters, because it affects how we understand our relationship to distant or nonlocal information if our brain is indeed a search engine. The fact that the associations used by our search system are built up through life experience may in the end be all the difference between the future and the past: the past—or, one’s own past—is that which has been accessioned, like a library or museum collection. It is that accessioned stuff that must provide the initial breadcrumb trail of associations leading us to the new and unfamiliar. (It also suggests why research with UFO witnesses must be, as Vallee suggests, a process, unfolding over time, to excavate personal meanings and associations, not unlike a psychotherapeutic relationship.)

The Eyes of Heisenberg

There may be no physical spaciotemporal barrier to accessing all information, anywhere, anytime; as information formations, we are all made of the same stuff. There’s no real discontinuity between “me, here, now” and what’s happening on Gliese 667c, or what will happen there in a million years. But in order to find out what is happening there and then, I must be able to formulate a question—what I want to know—in precise enough terms to retrieve an answer from the cosmic database. That’s tough, because I don’t know what I don’t know; and, I wouldn’t recognize the needed information if I did retrieve it, or have any way to judge its accuracy.

Psi may only be functional—and useful—when the psychic eventually has an experience that definitively confirms or disconfirms whether or not he/she “got it right.”

This happens to be the basic epistemological quandary that led Plato to conclude that all learning is actually remembering, or anamnesis. Basically, we don’t know what we don’t know, so there is no way to know something new that we didn’t already know before, in a previous life. This would fit pretty well with today’s consciousness-centric philosophies like Kastrup’s—that the self with its brain-image is a “dissociated alter” of a larger singular all-knowing “Mind at Large”; everything we don’t know is really what we have forgotten we know or forgotten we could know, if we only knew how to ask.

It also suggests why psi may only be functional—and useful—when the psychic eventually has an opportunity to make a physical observation or otherwise have an experience that definitively confirms or disconfirms whether or not he/she “got it right.” It has been suggested that even what seems like remote viewing could in fact be precognitively seeing something like “the right answer” as it is confirmed during a feedback session at a later time—what I described elsewhere as the “scene of confirmation.” Psi researchers Edwin May and Sonali Bhatt Marwaha have suggested that all psi experiences are precognitive, and Vallee raised this possibility after a talk at the 2007 IRVA conference. It would indeed reduce some of the mystery about how we locate and access psychic information: Instead of somehow finding and accessing information omnisciently from the entire nonlocal quantum field, the psychic could be just drawing information from a single channel, a scene in his or her own future that is/will be linked by memory association to the remote viewing session itself.

Psychic experiences that are not confirmed are, well, not confirmed, and one must beware of circular or tautological psychic claims, of which there are many. The great pitfall claiming the minds and careers of some of the original Star Gate viewers seems to have been attempting to view uncorrelated (or unconfirmable) targets like UFOs or historical events like the Crucifixion. There seems to be even something Heisenberg-like about psychic information: It doesn’t count as true or false—and thus, doesn’t really exist as “information”—unless and until some real state of affairs is observed physically by the psychic him- or herself.

As I have argued, the precognition theory can also explain synchronicity. Insofar as we are ignorant of the functioning of precognition in our lives (the crucial Lacanian dimension of misrecognition), we would dissociate from, disavow, or more generally just misattribute and misinterpret information that came to us via this channel. The same way that subliminally or unconsciously acquired insight and knowledge can be misattributed to another intelligence interacting with us, future information would be misattributed to present or past circumstances—the “temporal bias”—and in certain extreme cases this would produce jarring experiences of “meaningful coincidence”: a feeling that the cosmos had stage-managed events to provide some indication to us or give us needed information.

Even with Melchizedek, the “time-loop amplification” model I proposed could explain it: In other words, the amazing experience of reading a cab receipt with the name Melchizedek on it could have primed Vallee, months or years earlier, to notice that name on a Paris metro wall. The name on the receipt would have been “amazing” (and thus sent ripples back in time along the resonating string of his creative jouissance) because of the intellectually exciting intervening life events (researching the Melchizedek group, etc.), which unfolded because of that priming.

Even with Melchizedek, the “time-loop amplification” model I proposed could explain it: In other words, the amazing experience of reading a cab receipt with the name Melchizedek on it could have primed Vallee, months or years earlier, to notice that name on a Paris metro wall. The name on the receipt would have been “amazing” (and thus sent ripples back in time along the resonating string of his creative jouissance) because of the intellectually exciting intervening life events (researching the Melchizedek group, etc.), which unfolded because of that priming.

As preposterous as they sound on the surface, such time-loop structures must exist if information can travel through time and influence the past, because our resulting actions would have to be able to feed back on that future information (or else negate it, which is probably the more likely outcome—the other butterfly wing of the strange attractor in the dynamic systems space of psi). Jung was right to call synchronicity “acausal” if we take that to mean this kind of tautological chicken-and-egg logic. In his TED talk, Vallee himself invoked a similar “double causation” synchronicity theory advanced by Philippe Guillemant: “Our intentions cause effects in the future that become the future causes of present effects.” A meaningful nexus like “Melchizedek” may be a kind of symptom-vortex acting as an attractor for a person’s unconscious jouissance—or what in Lacanian terms is called a “symptom.”

Physics of Omnipotence

Quantum physics leads tentatively to the conclusion that we are potentially omnipotent as well as omniscient, given the necessary role of conscious observation in collapsing wave functions and thus converting possibilities to actualities. The $64,000 question is, does psi “observation” by itself have a similar effect? Is following that breadcrumb trail of tokens and search terms—or traversing events by association—just accessing information via the brain’s associative search engine (associations built up over a lifetime of idiosyncratic experience and dreaming), or is it also co-creating the reality it is searching for?

is following that breadcrumb trail of tokens and search terms—or traversing events by association—just accessing information via the brain’s associative search engine, or is it also co-creating the reality it is searching for?

One possibility I’ve raised previously is that the difference between psychic perception and embodied observation might be that the former only “sees/knows” certain probable or likely outcomes in a still-indeterminate condition of Quantum superposition. This seems likely to me, because otherwise precognition would actually amplify determinism, collapsing the wave functions in front of you and thus solidifying your fate. Viewing the future psychically, I propose, should not be able to force it to come true (I shouldn’t think). Thus here again, it really all comes down to those “scenes of confirmation”—the physical observation of outcomes. Such scenes may play a crucial role in the circuit of psi and the manifestation of our psychic intentions. It also raises questions about the real mechanism at work in, for example, cases of PK and psychic healing. Are intentions really acting at a distance in the present, or are they actually leading us to collapse wave functions at a future scene of confirmation, as in the precognition model of ESP/remote viewing?

If the latter is the case, it could explain a lot of baffling problems in science, like the tendency not only in psi research but in all research for results to conform to experimenter expectation (I’ll return to this in future posts). And again, this idea might also illuminate why psi leads to such a quagmire of deception and paranoia when it is deployed against “uncorrelated targets” like alien intelligences, UFOs, or the Loch Ness Monster.

Tangentially, this notion could also unify my “psychic astronauts” and “noöverse” hypotheses. Any psychic exploration of spacetime might require embodied machine proxies to help conscious beings back home confirm and thus assist in the waveform collapse that makes psychic “seeing” (not to mention world-creation) reliable. If some subset of UFOs are, as I have speculated, nonsentient drones, they may nevertheless be an essential component in somebody somewhere’s “psychic space program” (or, perhaps, “psychic dimensional program”).

* Jim Schnabel’s book Remote Viewers omits Vallee’s crucial contribution, the use of geographical coordinates as an addressing scheme, claiming instead that Swann thought up the idea himself one day while lying by the pool. Vallee’s more detailed and, I am sure, more trustworthy account appears in his Forbidden Science, Vol. 2; he also discusses it in his IRVA talk.

Strange Animals in the House of Knowledge: On Forteans & Paranoia

Scientists always seek better ways of aligning their categories with what they take to be preexisting ruptures or boundaries in nature—the idea of “carving nature at its joints.” I love that phrase, because I have always been troubled specifically in certain divey Chinese restaurants when I see a fowl like a chicken or duck being cleaved contrarily to my Western understanding of anatomy, like through the middle of a leg or horizontally across the middle of the breast. Asian cooks seem to follow a completely different conceptual map of the animal, one that pays much less attention to skeletal structure—and joints—than I would.

It always reminds me of Borges’ fictitious Chinese encyclopedia, the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, in which animals are divided into the following categories:

Those that belong to the emperor

Embalmed ones

Those that are trained

Suckling pigs

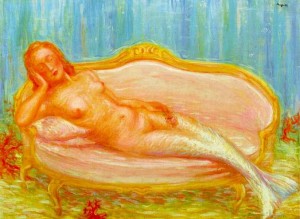

Mermaids (or Sirens)

Fabulous ones

Stray dogs

Those that are included in this classification

Those that tremble as if they were mad

Innumerable ones

Those drawn with a very fine camel hair brush

Et cetera

Those that have just broken the flower vase

Those that, at a distance, resemble flies

“Paranoia” is in some sense just an unkind diagnostic epithet for people who draw connections that cut across hallowed cultural boundaries, connections that others cannot or do not wish to see.

This mad classification system is jarring (and funny) because it upsets our implicit Western understanding of logic, which is based on exclusive categories and nested sets, not sets that inevitably overlap (such as “belonging to the Emperor” and “Those that have just broken the flower vase”). Borges’ encyclopedia inspired the structuralist philosopher-historian Michel Foucault to write a whole book, The Order of Things, about the slowly shifting conditions of discourse that define knowledge in a given culture and time, or what he calls an episteme. Thinking about our own cultural categories, and what is thinkable and speakable within them, is crucial for understanding the marginal position of Fortean and paranormal topics within the modern, Western episteme.

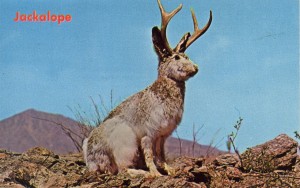

The paranormal, as George Hansen

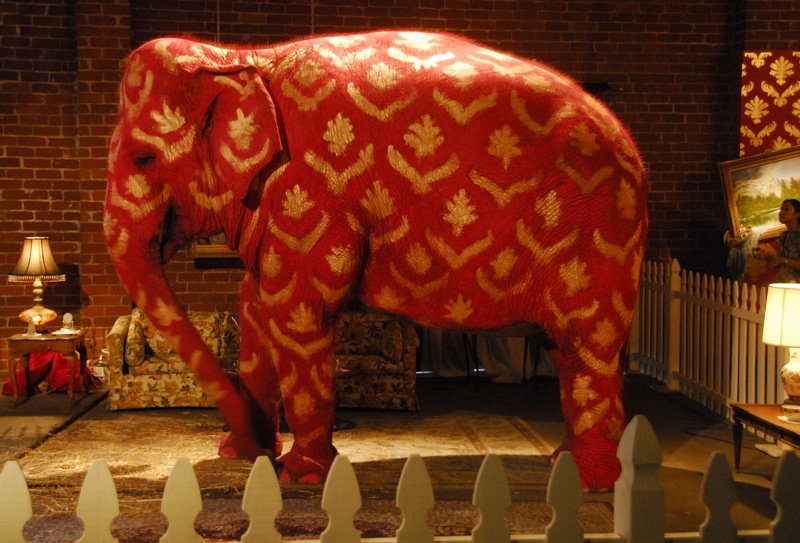

The paranormal, as George Hansen has shown, consists specifically of boundary-crossing things, things that fall in our cultural cracks. These cracks are dangerous and dirty. He cites anthropologist Mary Douglas, who described how whatever transgresses boundaries or doesn’t stick within the confines of our familiar conceptual fences is experienced with revulsion. For instance, pigs were regarded as unclean by the ancient Hebrews because they were cloven hooved, like cows, yet did not chew a cud; it violated their cultural logic. Or, something as innocent as soil may be experienced as disgusting or repellant (i.e., as “dirt”) when it is tracked into a modern home, because it then violates the implicit boundary between “nature” and “culture.” (Protestants and other clean-freaks often respond to stray dirt in an apoplectic manner unbefitting its objective harmlessness.)

Fortean topics are perfect examples of the repulsive aura that surrounds boundary-crossing subjects. UFOs and ESP and Bigfoot, when talked about seriously, are repugnant to the mainstream mind, and mentioning them can put people off on a very fundamental level. There is some way in which these topics, in their inappropriate betwixt-and-between-ness, resemble private or even shameful bodily functions, or indeed dirt. This is beautifully depicted in Close Encounters, when UFO witness Roy Neary crazily drags dirt and plants into the family living room to assemble his Devil’s Tower model, as the neighbors look on in pity. The more we Forteans and anomalists display our strange, transgressive obsessions, the more the world shuns us as unclean, for reasons that are deeply epistemological. Thus being a Fortean can be socially (or at least, intellectually) isolating.

The Paranormal and Paranoia

People are repelled by margins, and they also distrust those whose minds are comfortable dwelling there. “Paranoia” is in some sense just an unkind diagnostic epithet for people who draw connections that cut across hallowed cultural boundaries, connections that others cannot or do not wish to see.

Nash himself said “I wouldn’t have had good scientific ideas if I had thought more normally.”

It goes without saying that there is a lot of paranoia in the Fortean world. As Hansen shows, paranormal topics tend to lead to paranoid thinking in those who go down the rabbit hole of UFOs, parapsychology, cryptozoology, and related areas of interest, although there is also a factor of self-selection: People who appear to be made paranoid by the study of the paranormal may have been in some sense paranoid to begin with; a nicer way of saying this, though, is that they start out open-minded and intellectually curious. In the cross-cutting demographic that attends to anomalies, you get a lot of people whose minds make connections that other minds don’t. Forteans, unlike more mainstream thinkers, allow their minds to “go there,” wherever “there” may be.

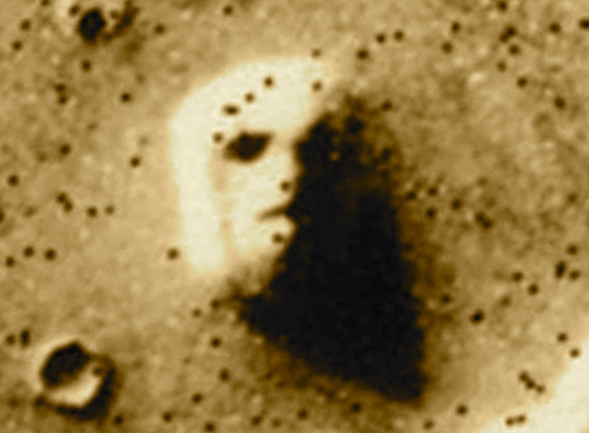

Scientific geniuses and artists are often pattern-seers too. Theories are patterns; new theories are made by people who have a knack for discerning them. When newly perceived patterns can be supported scientifically, it can push a field in new directions and rearrange our existing categories in ways that previously might have seemed as illogical as Borges’ encyclopedia. Thus to some extent, paranoia is always relative, defined in terms of a given episteme or paradigm. It is not often enough mentioned that great scientific theorists are usually guilty of creating some bad theories amid their better-known solid ones. A certain amount of theoretical ‘pareidolia’—if not true paranoia—just goes with the ‘genius’ territory.

Scientific geniuses and artists are often pattern-seers too. Theories are patterns; new theories are made by people who have a knack for discerning them. When newly perceived patterns can be supported scientifically, it can push a field in new directions and rearrange our existing categories in ways that previously might have seemed as illogical as Borges’ encyclopedia. Thus to some extent, paranoia is always relative, defined in terms of a given episteme or paradigm. It is not often enough mentioned that great scientific theorists are usually guilty of creating some bad theories amid their better-known solid ones. A certain amount of theoretical ‘pareidolia’—if not true paranoia—just goes with the ‘genius’ territory.

I was reminded of this a couple weeks ago with the sad death of John Nash and his wife in a taxicab accident. Nash, the Nobel-winning mathematician immortalized in A Beautiful Mind, also suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, and among his ‘delusions’ was the belief that aliens were attempting to communicate with him via The New York Times. It is an important reminder that you frequently can’t have penetrating insight without a degree of wild imagination (some would say lunacy, but who am I to say he wasn’t being contacted by aliens via the newspaper?). Nash himself said “I wouldn’t have had good scientific ideas if I had thought more normally.”

Us and Them

Yet even if we philosophically acknowledge Indra’s net, the ultimate interconnectedness of all things, some pattern-seeing is too much an affront to reason to be helpful or useful. And it can serve to perpetuate the social marginalization of Forteans, and this marginalization can in turn contribute to paranoia, in a kind of feedback loop. Being isolated both individually and as a (small) group makes it difficult to triangulate ideas and apply proper critical distance, creating a perfect breeding ground for the creeping seeing of (probably) illusory connections.

Forteans often contribute to their own exclusion by taking an antagonistic attitude to the mainstream.

I recently I wrote about Mars anomalies, for example: While there are a handful that are genuinely perplexing (including, I am now re-persuaded, the famous “face”), these are tainted by a vast array of items that range from the absurd to the sad, such as “cities” feverishly discovered in photographic compression artifacts or plainly ridiculous “animals” somehow wandering about the frigid Martian surface. A failure to exercise critical discernment, coupled occasionally with a truly well-intentioned and democratic “anything goes” attitude on such sites, effectively exiles the entire subject from any serious consideration by the mainstream.

Forteans often further contribute to this problem of cultural exclusion by taking an antagonistic attitude to the mainstream, bitterly transforming the marginality of our areas of interest into some kind of conspiracy by the powers that be to hide the truth. Planetary anomalies and ufology are full of this kind of thinking, of course, but there is no area of Forteana that is untouched by it.

Forteans often further contribute to this problem of cultural exclusion by taking an antagonistic attitude to the mainstream, bitterly transforming the marginality of our areas of interest into some kind of conspiracy by the powers that be to hide the truth. Planetary anomalies and ufology are full of this kind of thinking, of course, but there is no area of Forteana that is untouched by it.

For example, I recently attended a talk by an outsider archeologist presenting very interesting epigraphic evidence for pre-Columbian presence of Celtic and other European and Mediterranean peoples in the New World, possibly as part of multicultural crews of ancient Phoenician trading vessels. While his evidence was compelling, he characterized mainstream archaeology’s resistance to this evidence in implicitly paranoid terms: “We’ve been lied to,” he said more than once, and compared the edifice of mainstream academic archaeology to a priesthood jealously preserving its hegemony against outsider thinking. It’s an unfortunate attitude that is both unhelpful to the cause of paradigm-shifting and also betrays an ignorance of the sociology of knowledge.

The Knowledge System

Scientific and academic paradigms are subsystems within the larger system of academic knowledge, which itself is a subsystem within a larger episteme (in Foucault’s sense) as well as political-economic-cultural world. Thus paradigms are effects of a constellation of sociological, economic, and other forces, including pressures on publishing, tenure, grant funding, etc.—forces tend to be conservative. Whenever consensuses are forged, it advances a field of study, but it does so by ignoring disconfirmatory data. For a field to advance in any direction, anomalies must be swept under the rug; if and when enough of those anomalies accumulate, paradigms may shift, but again at the expense of data that would disconfirm the new paradigm. It’s the sort of lurching oscillation between openness and closure that characterizes all kinds of systems, from the weather to cortical signaling in the brain to political structures to religious movements.

Whenever consensuses are forged, it advances a field of study, but it does so by ignoring disconfirmatory data. For a field to advance in any direction, anomalies must be swept under the rug.

I am not an archaeologist, but I am sure that the academic “priesthood’s” resistance to pre-Columbian anomalies is not that they are suppressing some big truth that they want to keep secret, but simply that they are human beings working within a knowledge system, subject to the same pressures of prestige, reputation, and status that are the academic equivalent of capital in the world of trade for goods and services. Whether you are selling ideas or cars, you are going to be biased, because you’re human. You want the world to buy your car, or your anti-diffusionist account of ancient New World culture, not the shiny new product of some upstart competitor. Your culture of academic insiders is going to encourage scoffing and mockery of the competition, because face it, that’s what humans do. We’re cliquish and classist and can be nastily closed minded, especially when we are in our little professional groups. (It doesn’t matter what the profession—all are equally bad.) There are also larger forces of cultural and political correctness (ideologies) subtly exerting an effect on what is seeable and sayable.

Given the limitations on his time, a professor who has been teaching and writing his whole life that sustained Old World contact with the New World began with Columbus and his men (not counting that minor blip of Erik the Red), has no incentive to consider sparse and often poorly provenanced evidence to the contrary. It’s not that he’s knowingly “lying” to his readers and students. The academic consensus he has worked within his whole life may indeed cause him to not even see evidence that would support another theory; but again, this is just human, and not evidence for conspiracy or deception. The more the accumulating anomalous evidence comes in a paranoid package—as “revelation” of “secrets” that have been “silenced” and concealed by academic “lies”—the less incentive the tenured have to listen.

Given the limitations on his time, a professor who has been teaching and writing his whole life that sustained Old World contact with the New World began with Columbus and his men (not counting that minor blip of Erik the Red), has no incentive to consider sparse and often poorly provenanced evidence to the contrary. It’s not that he’s knowingly “lying” to his readers and students. The academic consensus he has worked within his whole life may indeed cause him to not even see evidence that would support another theory; but again, this is just human, and not evidence for conspiracy or deception. The more the accumulating anomalous evidence comes in a paranoid package—as “revelation” of “secrets” that have been “silenced” and concealed by academic “lies”—the less incentive the tenured have to listen.