The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

Humans Everywhere (the REALLY Anthropic Cosmos)

There is the important, often-heard argument that in our attempts to think about extraterrestrials and extraterrestrial intelligence we should not be anthropocentric—that aliens will be alien, maybe so alien that we have already encountered them and cannot even recognize that fact. This is one of the arguments against the extraterrestrial hypothesis for UFO encounters—that our visitors are universally humanoid in appearance, and thus surely originate somewhere (or somewhen) more local—like another dimension, or our own future, or the collective unconscious. Despite being a Star Trek fan, I myself always disliked the Star Trek vision of the unimaginably vast universe being populated by beings that look and act just like us except with minor differences in skin tone and forehead shape (a vision of extraterrestriality governed by the cheapness of TV makeup and facial prosthetics).

But while pushing alien-ness to its limits is an important exercise for stretching our imaginations, I am increasingly compelled by the anthropocentric-sounding idea that ETs might actually tend to look just like we do. Terrestrial examples of convergent evolution show just how powerful niches are at producing uncannily similar forms from widely different origins. A classic example is the thylacine, an Australian marsupial thought to have gone extinct in the 1930s but occasionally still reported and thus possibly still surviving as a small relict population in the Outback. Although its most recent common ancestor with canines would be some shrew-like creature way back in the Jurassic period (145-200 million years ago)—much older than its common ancestor with the kangaroo, in other words—it looks uncannily like a wolf, and old films of the animal show that it moves like a wolf and has similar mannerisms. This is because in an island continent with no canines, it evolved to fill the exact same niche, “apex predator,” that large canines did elsewhere. (Richard Dawkins reports that thylacine skulls were actually used to trick students in Oxford zoology exams.)

An advanced spacefaring species will have (at least at some point) occupied the same niche on its planet that we do now on ours—what you might call “apex animal”: a highly social, tool- and machine-using species having gained mastery over the planet’s raw materials and other species through its intellect, physical dexterity, and complex social organization and culture. These capabilities in and of themselves don’t necessarily predict having a humanoid body plan—one could imagine a super-smart, social, tool-using amoeba or octopus or a big-brained cockroach. But to arrive at those capacities, that species would need to have undergone certain pressures and constraints over its long evolutionary past that would narrow the realistic range of forms it could actually end up taking.

The Anthropic Path

Principally, such a species would need to have come up via an early threshold of tool manufacture and use coupled with complex social manipulation. That means, I suspect, being land-dwelling (rules out soft body forms like octopi), being of a certain size to support a large brain (rules out amoebae), and having an endoskeleton (rather than exoskeleton) that can support that body size on land (rules out cockroaches).

More to the point, such a species would have to have manipulating appendages—minimally two, so they can coordinate and work in opposition—but (and this is important) those appendages would have necessarily evolved from structures serving some other purpose like locomotion, through a process of exaptation (existing traits assuming new functions). Major organs and limbs with specialized duties don’t just spring into being fully formed. Thus, the original body plan would have had at least double this number of locomotor appendages so that, through said exaptation and related changes, it could concentrate locomotor duties on the remaining ones. For land animals over a certain size, more than four legs is redundant and impractical, so more than likely, the ancestors of our hypothetical species would have been quadrupedal, while it itself would be a biped with arms terminating in something like hands.

Our big social and tool-using brain coevolved with our dextrous hand and opposable thumb. The two are inseparable in our evolution, in fact, and not simply because of tool use. Manipulation of the social world was just as key to our development of higher intelligence as manipulation of the physical world, and we know they occurred together. The parts of the brain that handle language remain closely connected to those that control manual manipulation and dexterity, and in fact language is now thought to have evolved from gesture, not from primitive vocalizations.

It’s an interesting story how the shifting duties of our feet and hands changed our head (and vice versa): As bipedalism freed the hands for tool use, tool use (specifically, knives and fire) freed the jaw from its biting duties and relieved much of its chewing duties. This both flattened the face and enabled the oral cavity and breathing apparatus to become more elaborate so the production of vocal language could take over and expand the former job of gesture—creating the beginnings of symbolism and freeing the hands now to concentrate fully on manipulation of the physical world. All the while, of course, the cortex was ballooning to manage these new capacities as well as drive them. Notably, the transition from gesture to vocal language enabled communication to be “silent” and thus gave rise to a whole inner world of self-talk, a watershed development in the history of self-consciousness.

Bipedalism is significant in this story not only because it freed the hands for other things but also because it imposed a restriction on the diameter of the birth canal. This restriction on a massive-brained creature forced “premature” birth and thus prolonged postnatal vulnerability, necessitating lengthy maternal care and socialization and thus enculturation—the emergence of an extrasomatic memory, the beginning of culture and memes as a parallel form of inheritance to genes.

All this is to say there was a parsimonious relationship between intelligence and manipulation of the social and material world, and they occurred of a piece. The structure of the forelimbs, the shape of the face, the shape of the head, the shape of the pelvis, and the upright stance all evolved together as part of a single trajectory within an emerging milieu of symbolic cultural knowledge and memory (the emerging noösphere), each of these traits feeding back on the others, creating a “perfect storm” of pressure to become humanoid.

Any form in nature or art reflects a kind of compromise among various current pressures and those that shaped it in its past; indeed, the main current pressure on an organism is the inertia of its own history. Having, say, an extra couple of hands or, heck, wings might seem useful, but there’s no structural precedent for it. Imagining the bizarre forms ETs could take is a fun exercise, but all too often it leaves out the boring story of where the being had to have come from. I don’t think it simply reflects a failure of imagination (or reactionary anthropocentrism) to suggest that our erect, bipedal plan couldn’t be a more realistic, simple solution from the standpoint both of our future potential and our past history—where we are going and where we came from. In the future, we may be able to jettison most of the physical body that got us to this point, but that body is still like the enormous first stage of an Apollo rocket—it was completely necessary to get us into the “space” of higher intelligence, and I really wonder whether it could have happened any other way. I suspect all these same factors will have driven the rise of intelligent beings elsewhere; and even if such beings transcend to become “posthuman” machines, that humanoid past will nevertheless leave some kind of imprint on their psyches, culture, or spirit.

Are ETs Our Confluent Kin?

The 20th-century Hermetic philosopher Rene Schwaller de Lubicz argued that all biological forms contain and prefigure the human body and soul. As retrograde and ignorantly teleological as that idea may seem in our postmodern, ecological, anti-anthropocentrist age, I think Schwaller’s idea is worth at least pausing to consider, if only as a thought experiment. What if the forces giving rise to higher intelligence are so similar in biospheres throughout the universe that not only the humanoid body plan but even the “human spirit” are Cosmic universals? I suspect that, just as intelligent extraterrestrials will frequently (if not always) pass through a humanoid phase at the culmination of their biological evolution, they will also reflect (at least in that phase) the same motives, conflicts, ambitions, insecurities, desires, fears, hopes, etc. that we do, because their history, like their evolution, will reflect the same opposing forces and pressures. Again, this will undoubtedly leave an imprint, of some kind, on their posthuman trajectory.

We could even take this speculation one step further. Some astrobiologists speak of a Galactic Club of sufficiently advanced technological civilizations who share their knowledge with each other. What if our destiny is really, literally, to join a Galactic Family? What if the ages-old intuition that our visitors’ involvement with us has to do with breeding or hybridization reflects a kind of four-dimensional model of Cosmic kinship, in which all intelligences throughout the Cosmos converge, not merely on a body plan but even on a shared genetic code?

Maybe there is something to the Hermetic intuition that Anthropos, some fully human being, stands at the end of Cosmic history, as its completion and pinnacle. I’ve always disliked the warm and fuzzy vision of universal brother- and sisterhood espoused by some UFO believers and expressed (for example) at the end of Close Encounters. But what if we actually share with ETs not a common ancestor in the past but a common descendent in the future, a Star Child? Perhaps “confluent” kinship should be the central organizing concept for reckoning Cosmic relatedness in a future exoanthropology.

____

UFOs and Animals

Mac Tonnies, a UFO lover and a cat lover, saw a connection between how UFOs behave and how we behave around our animals. He noted that UFOs behave an awful lot like laser pointers, and their effect on us is similar to our toys’ effect on our pets.

Mac Tonnies, a UFO lover and a cat lover, saw a connection between how UFOs behave and how we behave around our animals. He noted that UFOs behave an awful lot like laser pointers, and their effect on us is similar to our toys’ effect on our pets.

I couldn’t help thinking of this last winter when a video from Norway (embedded below) briefly went viral—a POV of a quadcopter drone encountering and descending on a moose, accompanied by the vocal delight of the drone operator and his friends. I don’t understand Norwegian, but their surprise and joy is clear from their laughter, and the moose shows no fear, and even approaches the drone in curiosity. It is indeed somewhat magical, a strange new way of achieving “communion” with a fellow creature.

I’m a great fan of trailcam photography, both for cryptozoological and more mundane purposes (the picture above is of bobcat kittens in my mom’s yard in Colorado), but drones open up whole new possibilities for animal watching and interaction. The moose video made me want to get a quadcopter myself, so I could (I imagined) explore the neighborhood and visit animals with it—a raccoon up in a tree, a deer and her fawn, a flock of geese, even a lonely dog in a backyard. I imagined how fun it would be to be, in effect, a UFO in the lives of animals—to descend into the life of a creature, be able to watch it up close, and interact with it—not scarily (certainly not cruelly) but maybe teasingly, playfully.

Play is learning (among other things). When I play with my animals, I am learning about them, always finding some new nuance in their personalities, their selves. I wonder if it would be any different if I was a UFO and Earth was my beat?

If, as I’ve speculated, many UFOs are knowledge-gathering probes or even automated science platforms, then I wonder what percentage of their activity on Earth is really centered on us humans? Our animal friends large and small may have many more UFO experiences and close encounters (and I’m not merely referring to the troubling question of animal mutilations) than we do.

Animals in my dream life are bizarre, beautiful, and inspiring. I suspect that if I were given the opportunity to visit other planets or other dimensions or other times, I would be as fascinated by the alien fauna as I would be by the local “intelligent civilizations”—maybe even more so.

___

Does a Flying Saucer Have Buddha Nature?

In The Invisible College, Jacques Vallee noted that situations reported by UFO witnesses and abductees “often have the deep poetic and paradoxical quality of Eastern religious tales.” In a 1978 interview with Fate magazine, he elaborated on the insight that UFO encounters are like koans: “If you’re trying to express something which is beyond the comprehension of a subject, you have to do it through statements that appear contradictory or seem absurd. For example, in Zen Buddhism the seeker must deal with such concepts as ‘the sound of one hand clapping’—an apparently preposterous notion which is designed to break down ordinary ways of thinking.”

For Vallee, the absurd and even ridiculous “meta-logical” quality of messages and scenarios reported in the close encounter literature suggest UFOs are a kind of “control system” that is manipulating our consciousness and history—either deceiving us or trying to elevate us or some mix of both. I’ve always liked this idea of treating UFO reports, and our own UFO experiences, as koans (and I think, whatever “their” intent, just following the remarkable chains of thought inspired by UFOs, or the paranormal in general, can be a gnosis, as Jeffrey Kripal argues).

For Vallee, the absurd and even ridiculous “meta-logical” quality of messages and scenarios reported in the close encounter literature suggest UFOs are a kind of “control system” that is manipulating our consciousness and history—either deceiving us or trying to elevate us or some mix of both. I’ve always liked this idea of treating UFO reports, and our own UFO experiences, as koans (and I think, whatever “their” intent, just following the remarkable chains of thought inspired by UFOs, or the paranormal in general, can be a gnosis, as Jeffrey Kripal argues).

The earliest Zen koans did not just consist of direct questions like “the sound of one hand.” Many were records of interactions, “public cases” (the literal meaning of koan) in which past masters and their disciples tested each other, using provocative actions or answers to questions. The most famous and widely used koan in the Rinzai Zen tradition is known as Mu, the Chinese word for “no.” It’s relatively short, as koans go:

A monk asked ZhaoZhou, “Does even a dog have Buddha nature?”

Zhaozhou said, “No.”

Such an exchange, which in this case defies what “everyone knows” (that all sentient beings have Buddha nature) initially provokes endless logical interpretations—the master is joking, the master is being ironic, the master’s “no” isn’t an answer but an admonishment (the way you might admonish a dog) for the monk’s asking of the question, and so on. The student assigned this koan goes back and meditates on it at length—chews it rather the way a dog chews a bone. In regular interviews with the master, the student shows what he or she has come up with, and usually is told to go back and continue working. Eventually after weeks or months or years, the student’s mind, maddened and frustrated, exhausts all the hundreds of logical possibilities, and at this point may be ripe for a nonconceptual understanding to break through and wash out all that logic, like the bottom dropping out of a bucket. This is the breakthrough moment of satori.

There often wasn’t a single correct answer to the koan, but the student would produce some appropriate response showing his or her newly altered state of mind, and the master would see that the student had authentically broken through. In no case is the test passed by providing a conceptual, logical sort of response or an intellectual interpretation like you could express in a report. Zen is beyond logic. I’ve read that in the case of “Zhaozhou’s Mu,” some students who have had a real breakthrough just happily bark “No!” at their teacher.

In other words, a koan was a meditation tool, but it was also a test. A real master can always tell when the response is authentic, by a student who has had an enlightenment experience, or if it is a pretense or imitation.

In 2001, Arthur C. Clarke envisioned an alien race using its technology both to cultivate us (the slab that appears at the Dawn of Man to teach us violence and tool use) and to serve as a sentinel, an automatic alarm system to alert them once we’d arrived at a certain technological threshold (the slab millions of years later, on the moon). Wherever the intelligences interacting with us via UFO encounters come from, and whether or not any of them have a behavioral modification plan for us, they may be patiently testing our readiness for a more spiritually and philosophically mature, “meta-logical” interaction. In our persistence in taking the whole phenomenon literally, in trying to provide rational explanations and, as Vallee put it, “kick the tires,” we display the same obstinate conceptualist, materialist limitations shown by Zen monks parading out their various logical interpretations of “No” … until they eventually get it.

I think it may be necessary to go through this “nuts and bolts” phase—thinking about where UFOs come from, their propulsion systems, government coverups, etc., producing all our clever, logical speculations—in order to wash out our own minds. Once we do that, the pointlessness of our conceptual thinking may finally hit us and we will finally be able to just quietly, smile, and nod, like the disciple Kashyapa when the Buddha wordlessly held a flower up—the origin of the Mind transmission that eventually became Zen.

(I sometimes wonder if some in the UFO community who have largely fallen silent, such as Vallee, are already there in some sense, their relationship to the phenomenon more spiritually advanced than the rest of us suspect.)

The Noömass Hypothesis: Is Dark Matter Made of Knowledge?

. . . In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. (Borges, “On Exactitude in Science”)

I’ve argued previously that the idea of expanding spheres of colonization—ships full of families settling on new planets, having more families, etc.—fails to reflect our own destiny as immortal creatures and thus may be an unlikely agenda for extraterrestrial civilizations either. Yet if we confine interstellar “expansion” to the expansion of the noösphere, the enlargement of knowledge of the cosmos, then a more realistic picture emerges, one that conforms not at all badly to the long history of human interaction with seemingly nonhuman technology (leaving aside humanoid visitors—I’m referring mainly to orbs, spheres, and other technologies that don’t seem like they have little pilots inside).

Mathematical models (such as presented in a recent article by two mathematicians in Scotland, Arwen Nicholson and Duncan Forgan) dictate that the earth should long ago have been visited by extraterrestrial Von Neumann probes. As I suggested in a post on such probes, it seems reasonable to assume that since long before there were people and even long before there was life here, this planet has played host to automated surveillance technology, roving science platforms, probably having multiple origins but “living” right here. And we’d be unexceptional—just one of billions of worlds similarly swarming with intelligent surveillance machines taking various forms.

Needless to say, such a knowledge-gathering project undertaken for billions of years by numerous separate ET intelligences would produce, over the aeons, more than mere mountains of data. There would need to be some material or energetic substrate or “server” to support this knowledge. What if the invisible “dark matter” that is needed to make our current cosmological models consistent consists partly or even entirely of noömass, matter/energy that has been metabolized into information and that advanced intelligences have perhaps sequestered into the very folds of spacetime?

Borges imagined a map as big as the country it represented; perhaps there are already many maps nearly as big and as detailed as the rest of the (dwindling) universe. It may not be only a known universe but a multiply known universe—known and re-known many many times over, in such detail that it can be inhabited and manipulated and remade for countless alien experiencers, countless knowers ancient and immortal, some of whom arose long before our planet even formed. Their ubiquitous drone science platforms scour and record “all that is knowable” and, ultimately, may assimilate the rest of the universe (what is left, what we still see with our telescopes).

The Russian Cosmist Vladimir Vernadsky, who first coined the term noösphere, was referring to the collection of human scientific knowledge, the sheath of “thinking matter” that surrounds the earth; it is a concept that has been compared to the “Akashic Record” consulted by clairvoyants in the Theosophical and Anthroposophical tradition. What if the collected record of the entire Cosmos, mechanically archived and updated by the ancient machines of dawn sentiences, is really out there (and everywhere)?

“V’ger” in the first (and I think way underrated) Star Trek movie was an ancient, autistic machine intelligence scouring the galaxy to “know all that is knowable,” assimilating everything into a vast, hyper-detailed representation. I wonder: Could just a few thousand or a few million V’gers across the universe, all with the same idea, end up devouring the whole thing, metabolizing the unknown into the known?

The “known universe,” in other words, could be just that, literally: known, and in far greater detail, by someone else, or lots of someone elses. What’s missing from what we see—all that “dark matter”—could be precisely their knowledge of what we see, which includes their knowledge of us.

Perhaps we should give up looking for radio signals and dim Dyson Spheres (imagining advanced extraterrestrials to still be biologically based “civilizations” huddled around their stellar campfires) and start looking for pure information, something like the Akashic Record, more massive than the visible universe, enfolded in the fabric of spacetime itself.

___

Existential Futurology (A Few Thoughts on the Unlikelihood of Interstellar Colonization)

According to various estimates, including a mathematical model published a couple years ago by Thomas W. Hair and Andrew D. Hedman, the galaxy (let’s limit ourselves to our galaxy for purposes of discussion) should already have long been colonized by a spacefaring civilization. That our solar system appears to be untouched can only mean (according to such models, and ignoring UFOs as possibly representing an ET presence) that we are alone in the universe, that we happen to be in some undiscovered backwater, or that our planet/star system was in some other respect undesirable for colonization by ETs that long preceded our arrival on the scene.

But there is another possibility that I think is much more likely: that “colonization,” the perpetual expansion in search of resources and Lebensraum—literally “living room,” space to spread out and flourish—may not be a relevant motive for advanced intelligences beyond a certain technological and social threshold. The relevant threshold I’m thinking of is specifically that of immortality.

But there is another possibility that I think is much more likely: that “colonization,” the perpetual expansion in search of resources and Lebensraum—literally “living room,” space to spread out and flourish—may not be a relevant motive for advanced intelligences beyond a certain technological and social threshold. The relevant threshold I’m thinking of is specifically that of immortality.

To see why immortal extraterrestrials might never embark on galactic colonization, let’s project forward into our own future and see why we ourselves might not take such a path.

World Enough and Time

We are right on the cusp of being a spacefaring species, but space technology is proceeding in parallel with technological advances in health and bioengineering. We are within a century of technological breakthroughs that will greatly if not indefinitely extend the lifespan of human consciousness, via significant biomechanical augmentation of the brain’s support systems if not the actual “uploading” of our minds to computer substrates (which I’m personally skeptical of, but that’s another topic).

Dmitri Itskov, for instance, predicts immortality will be achievable by 2045—about the time Ray Kurzweil predicts his “singularity.” I suspect it will take longer, especially for such technology to trickle down to the masses, but such developments are probably nevertheless inevitable. We should remember that even a “significant advance” in longevity during present lifetimes could be the tipping point, because then people will, as Kurzweil puts it, “live long enough to live forever”—that is, live long enough to take advantage of further advances and then further ones beyond that, bootstrapping ourselves to immortality.

More than even robotics, AI, and big data, immortality will be the biggest game changer for how our descendants inhabit and utilize space—and not in the way Malthusians would suppose. While longevity will for a while continue to contribute to increased population growth (because old people would not die and make way for new people as quickly), it would ultimately also change social values about the family. If our offspring cease to be the only way we can live on, then will having children be as strong an imperative? Will “be fruitful and multiply” continue to be a social imperative for our species?

I suggest it wouldn’t. We should not assume that the “joys of parenthood and family life” are eternal; the Catholic Church notwithstanding, these imperatives belong to the regime of “the selfish gene,” which a technological singularity would enable our descendents to transcend, freeing us for other projects and ambitions that may prove far more rewarding than the hassles of pregnancy, childbirth, and caring for toddlers. The imperative of reproduction is likely to dwindle and may even wither altogether; at best, it will slow to a glacial pace. Certainly, we can imagine “selfish memes” taking the place of selfish genes, but the perpetual cycle of death and reproduction of space- and resource-utilizing meat substrates for those memes would not be part of that picture.

Expansion of habitats, putting pressure on an environment in terms of resources and space, characterizes biological species driven by a reproductive imperative and economics of scarcity, and this is the mindset that imagines us needing and wanting to venture out into space. But I suspect immortality (coupled with new energy sources on our own doorstep) will put an end to the need for ever-expanding Lebensraum before humans get very far beyond our own solar system, if even that far.

The Death of Heroism

It is kind of counterintuitive, but the longer our potential lives are, the more fearful death becomes, not less. Life in the past was relatively cheaper—people died sooner, were sure of death’s inevitability and believed in an afterlife, and were thus willing to take more risks like setting sail in ships for distant shores where the transit was perilous and the outcome uncertain. By contrast, if a person has a potential lifespan that is indefinite, with the whole of history ahead of them to experience and enjoy, will they risk that by putting themselves in any kind of harm’s way? I suspect immortality will put a damper on our species ‘extroversion’ by reducing the personal risks individual beings are likely to subject themselves to.

Remember, future humans will have gotten where they are through science, and the ideology of science is materialism. The materialist view is that the mind is nothing but a function or at least an epiphenomenon of the central nervous system, and thus this organ, the brain, will be the focus of life-preservation and belief in the afterlife will continue to diminish. This is already happening. More and more people, including nonscientists, are coming to believe that “this is all there is,” and the mind, our consciousness, all that we are and were, begins and ends with our brains. (I don’t agree with this, but I am not that optimistic that materialism will be supplanted by a spiritually higher, less death-afraid philosophy.)

You can’t replace a brain and have continuity of consciousness (in the materialist view), thus no amount of “copying” will substitute for this holy grail of immortality—preservation of brain function. Thus a potentially perilous journey across space would, for immortals, seem like not worth the risk. I suspect that our descendants will be the sorts of creatures who are afraid to cross the street and or go out their front doors (not that there will be streets or front doors), let alone make journeys into space. They will not see any point in risking their precious continuity of consciousness—whether that consciousness has an organic substrate or (as some transhumanists imagine) a machine one. Even in an armored, weaponized mecha body, this “center” of consciousness will remain vulnerable to loss through accident.

But in any case, why should they venture outward, when technology will wildly enhance their ability to journey, as it were, inward? We should remember: We are not talking about prolonging old age, but of prolonging and enhancing (healthy) existence in a rewarding, magical (in the Arthur C. Clarke sense: beyond-high-tech) world. Chemical and mechanical intervention will cure boredom and give that existence potentially endless new rewards and purposes. Those rewards and purposes could be base and hedonistic—what I think of as the H.R. Giger lotus-eating path to transhumanity—or they could be noble.

In a more optimistic scenario, the richness of future existence could be linked precisely to the project of robotic knowledge gathering I discussed in the previous post. The more worlds and lives brought back and simulated for virtual experience and learning, the more possibilities there would be not only for “entertainment” but also for growth and advancement.

The Future of “Authentic Experience”

We generally still devalue simulations and living life by proxy, as we maintain ancient philosophical distinctions about authentic versus inauthentic experience. What does it really mean to “experience something directly”? We conceptualize “direct” as near in space and time. Fundamental to our picture of experience is presence, being there. Presence has always been rooted in the organic body so we don’t yet know how to think of it otherwise. But technology is already altering and challenging the definitions of the body, and it will ultimately transform our sense of (and ideas about) presence and the authenticity of our experience.

Authentic contact is a kind of participatory magic. What it really boils down to is just sensory richness. The inadequacy and shallowness of current virtual reality is simply its smallness, incompleteness, narrowness, lack of resolution, few sensory channels, etc. Although we are experiencing bold leaps in this technology right now, our senses are still concentrated in our heads and our effectors are in our body, and augmentation of both is still relatively primitive and limited. We still engage virtually via small mediating devices that are middlemen to the experience—seeing a representation on a small screen, typing or manipulating a controller with our hands, and so on.

But as our senses become machine-augmented and technology enables communication of words, images, sounds, and ultimately tastes, smells, and touch, and even thoughts, “direct experience” won’t require these technical middlemen to sensory experience and action at a distance. The very meaning of “being there” will change.

Imagine you have an eye stalk, like a proper alien. Then imagine that eye is mechanical, like a drone, and replacing the stalk part with wi-fi. The eye can be “part of you” but float freely, even travel to another house or another city, and it is still transmitting direct to your brain. Then imagine many such eyes, and ears, and hands and sex organs to go with them. This kind of physical and perceptual dispersal will redefine our notion of our bodies. Light will be the new blood, and the new nervous system. It will significantly rewire our brains—indeed our brains will require continual rewiring to accommodate our radical physical updating.

In the future, our ability to not only perceive but also interact at a distance will be so integral to our experience that we will seem and feel ourselves to be less localized in space. In an increasingly postbiological and machine-integrated world, there will ultimately be no need to go anywhere. When a human living on Earth is able to fully “plug in” to a rich sensory proxy, for instance stride about (or hover) on Mars in a viewing, sensing robot, interacting with the environment richly, won’t this weaken our need or desire to go there in the flesh? It is easy to imagine that “in the flesh” will go the way of flesh itself: It will come to seem, ultimately, in a century or two, like something archaic or superstitious.

Nowhere Men

The liabilities of humans’ current format extend beyond our fragile, evanescent organic bodies and limited cognitive processing to include the very notion of “self,” which mystics of all traditions counsel is an illusion and the very source of our suffering. It seems likely that minds liberated from current physical constraints will also seek liberation from mental suffering and thus abdication of narrow self-views, and that technology will help in this.

It will be possible and presumably desirable to share our experiences directly, such that one person can sense on behalf of another distant person. I may be able to plug into your sense organs (if you let me) and you may be able to plug into mine (if I let you). With the radical possibilities opened up by replacing the physical body with endlessly modifiable polymorphous and spatially dispersed sensors and effectors that may be shared, not only our sense of “the body” but also our sense of individuality will be radically transformed. It may be that “the individual” goes away entirely.

And consider what possibilities open up when those roving eyes and ears and hands spread out across the universe. Imagine what rich simulations could be created from the data gathered by swarms of self-replicating probes doing “deep” science on every planet across the galaxy and beyond.

Consider this: Advanced immortal “gods” might even choose to play a game like giving up self-awareness temporarily, as in a dream, and experiencing the entire life of an animal or a being from a distant world, living out its existence in a rich simulation, and then experience the thrill of “waking up” from that life when the creature’s body dies, finding yourself back home, wherever home is. Given infinite time, you could do this indefinitely. (Michio Kaku suggests that the finite age of the universe will be no limit—as we approach the end of this one, we will just build new universes to escape into.)

If this sounds like Lila, the “God Game” of the Vedic scriptures, well, it is. It has already been suggested that we are beings living in a simulation. Another possibility is that we are already much more advanced beings who have forgotten that fact temporarily in order to feel what it is like to be human—that is, we are living in our own simulation. If that’s the case, and in the future we create and inhabit further simulations, then … well, it gets dizzying—simulations within simulations, gods within gods within gods, like turtles all the way down.

Approaching Rivendell

This picture, of cognitively hypertrophied, cowardly future beings turning inward into virtual worlds and simulations and exploring the universe by proxy sounds like a lot of dystopian science fiction, such as the Talosians in the Star Trek pilot episode “The Cage.” But to me it more closely resembles the immortal elven races in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien thought of his trilogy as a sort of thought experiment about immortality—what would happen in a world without death? It’s not an altogether bad picture. There’s nothing hedonistic and decadent about his elven race—indeed, they represent the highest civilization and progressive ideals, creating poetry and art and music of exquisite beauty. Yet by and large they are not heroic. They are reluctant, except when pressed, to leave their magic- (which of course equals high-technology-) protected enclaves or intervene in the history of the mortal races, beyond offering guidance and boons as necessary. As caretakers or custodians of Middle Earth, they are relatively hands-off, preferring to let mortals act in their stead.

Sometimes you will hear the argument that future humans will get bored with immortality and eschew it—and in fact, this was part of Tolkien’s thought experiment too: A few Elves here and there are bored and willing to trade their immortality for a mortal life, out of interracial love for instance. But these are the exceptions. I suspect it will be exceptional, too, for increasingly materialistic post-humans who believe or assume that their minds and selves are bound inextricably to their physical bodies and that there is nothing else awaiting them in some afterlife. They may suspect at times that they are gods who have forgotten that state, but how can they be sure? I suppose some advanced immortals may get bored with such a life and opt out, but as a species or civilization we will most certainly opt in and take whatever cyborg leaps that that entails.

My guess is that technological species elsewhere that survive their aggressive nuclear phase will colonize and exploit their own solar systems, but that by the time their technology enables fast space travel, it will tend to be their machine proxies—their remote sensing and interacting probes—that propogate through the universe on their behalf. They won’t need new homes for an expanding biological population—families homesteading on new worlds, etc., in a picture resembling our own colonial memory. They will have created a heaven right where they are, their experience ever-enriched by the knowledge their machines harvest from the remotest reaches of space and time.

—

Anti-Anti-ETH: Big Data, Deep Anthropology, and Von Neumann Probes

The recent NSA domestic spying scandal that shocked everyone is not really so shocking if you are the sort of person who likes to think about the possibilities (and pitfalls) of knowledge. We are now in the era of “big data,” which is changing the landscape not only of state surveillance but also science and health. Big computing power is enabling not only the gathering and storage but also the synthesis of exponentially greater amounts of information from scientific studies and clinical trials than ever before. In the halls of national research institutions, these new developments are being lauded (rightly) as heralding a new era of truly unprecedented scientific discovery.

Arguably, science itself is about to undergo a singularity, because the next step beyond big data collection is automating the very conduct of research to gather that data.

We all know how robots have or will soon take boring and dangerous tasks like vacuuming our floors or fighting our wars out of human hands. But no one thinks about the infinitely tedious task that is doing good science. In not too long, we will have the ability to automate not only the gathering and interpretation of information but also the very posing of research questions, and one of the first things we will teach intelligent computers to do is to ask questions in a scientific fashion—that is, form hypotheses based on prior findings, and then design and perhaps even (with the help of robots) conduct experiments to test them.

We all know how robots have or will soon take boring and dangerous tasks like vacuuming our floors or fighting our wars out of human hands. But no one thinks about the infinitely tedious task that is doing good science. In not too long, we will have the ability to automate not only the gathering and interpretation of information but also the very posing of research questions, and one of the first things we will teach intelligent computers to do is to ask questions in a scientific fashion—that is, form hypotheses based on prior findings, and then design and perhaps even (with the help of robots) conduct experiments to test them.

Whether artificial intelligence will ever become sentient (let alone spiritual) as Ray Kurzweil anticipates, AI will nevertheless be able to carry on the scientific endeavor increasingly independently, on a massive scale, fast, and without human biases and egos. This, whether we like it or not, will be truly objective science, which has never quite existed in the past even if it has always been the goal.

Space Probes Multiplying Like Rabbits

As long as we touch wood, Carl Sagan-fashion, and add “If we do not destroy ourselves,” the ability to automate science and deal with exponentially greater quantities of data will revolutionize our understanding of the natural world. Progress in medical research and many many other fields will make leaps and bounds, and it will ultimately revolutionize the exploration of space.

Because remember that, along with the big data and AI revolutions, we are also at the birth of the 3-D printing revolution. The use of local resources to create copies of machines and other supplies transmitted through space as simple information is going to make human life and work on the Moon and Mars and the asteroid belt feasible; and coupling a 3-D printer to a smart probe or drone will at last give us exactly what Von Neumann envisioned as the tool any advanced civilization will use to explore beyond its solar system.

Once a 3-D printer prints out another 3-D printer, the robot reproductive system is a reality. Interstellar probes thus equipped can replicate themselves at their destination and thus propogate from planet to planet, star system to star system, completely autonomously. Because they can perpetually repair themselves and reproduce, such probes would have limitless durability, and this would give them limitless patience. And what would limit them in the amount of reproduction that they do? Imagine: A thousand self-replicating probes are dispatched to the nearest star systems, where they copy themselves and establish a presence on every planet, if only to observe the geology and meteorology so long as nothing more interesting is going on, and send copies of themselves to further star systems, and so on. When they encounter really interesting stuff, like life or another intelligent species, they would swarm such a world with probes and dig in (quietly) for the long haul.

Such probes would have a built-in motive for curiosity and ability not merely to observe and record but to behave like experimenters: to generate their own hypotheses, design experiments to test them, and tediously replicate and re-replicate their findings alone or collaboratively, to constantly nuance and update their deepening understanding of their subject species. Such probes will not be passive, in other words, but will also interact in a very precise, deliberate, controlled fashion, and repeat these interactions obsessively in the same and different conditions, tirelessly, again and again and again, building up conclusions of high confidence. They will be more than “probes” as we usually think of them, but full, autonomous science platforms, continuously sharing data among themselves and constantly or periodically relaying that information to each other and back home for storage and future use by the civilization that built them (or their robot protectors).

Revisiting the ETH

Coupling the emerging reality of the Von Neumann probe with an expanding sense of just how “big” data could possibly get enables us to re-think some of the criticisms that have been leveled at the extraterrestrial hypothesis (ETH) in years past, because some are based on assumptions about the manner, scope, and aims of ET data collection that strike me as increasingly questionable.

Jacques Vallee was among the first ufologists to question the ETH. Vallee was in on the ground floor of the Internet and has been a technological as well as Fortean visionary throughout his career, and his argument against the ETH as an explanation for the full gamut of UFO contact experiences throughout history remains powerful and persuasive. I have come around to thinking he’s right—there’s a lot more to the UFO story (especially abductions and flying saucers) than flesh-and-blood aliens traveling across space to visit us. However, one of the five pillars of his argument—that the estimated millions of “landings” just in human history vastly exceeds what would be needed for a survey of our planet and civilization—misses what I suspect would be the very nature of any extraterrestrial “agenda” that was capable of populating space with swarms of robots and gathering and using big data over the long term.

In his 1989 paper “Five Arguments Against the Extraterrestrial Origin of Unidentified Flying Objects,” Vallee writes:

It should be kept in mind that the surface of the earth is clearly visible from space, unlike Venus or other planetary bodies shrouded in a dense atmosphere. Furthermore, we have been broadcasting information on all aspects of our various cultures in the form of radio for most of this century and in the form of television for the last 30 years, so that most of the parameters about our planet and our civilization can readily be acquired by unobtrusive, remote technical means. The collecting of physical samples would require landing but it could also be accomplished unobtrusively with a few carefully targeted missions of the type of our own Viking experiments on Mars. All these considerations appear to contradict the ETH.

Granted, it was 1989 when he wrote this. But besides predating the era of big data, this notion that ET space exploration would be satisfied with purely observational, “thin-slicing” data collection misses a whole side of science: experimentation and replication of findings. Remote, unobtrusive observation and periodic visits to collect samples would not remotely satisfy the scope of a full scientific research program on a potentially interesting planet such as our own. With massive data-gathering, storage, and synthesis capability wedded to machine self-replication, an “interesting” world such as ours could potentially have been swarmed with a hundred or a million probes, not only quietly observing and recording but also overtly interacting with the local flora and fauna for the purposes of experimentation and hypothesis-testing over the full course of its history.

Control Systems vs Psych Experiments

One of Vallee’s most far-reaching insights about UFO contact is that there is a regularity to it, a kind of ‘irregular regularity’ reminiscent of a reinforcement schedule in behavioral research. This insight supported his theory that UFOs may be some sort of control mechanism. The question is, control for what purpose? That UFO encounters represent an effort to shape our evolution is a popular view, and it could well be true in some cases. Yet the simple, scientific collection of behavioral data is another possibility that, despite what Vallee argued, is not at all inconsistent with either the the absurd, symbolic nature of UFO encounters or with their sheer number and repetition throughout recorded time.

First—and here I’m sure Vallee would agree—UFO encounters of all kinds (not just alien encounters or abduction experiences) not only resemble Zen koans but also resemble the contrived, surreal, occasionally uncanny situations that experiment participants find themselves in in any campus psychology laboratory. Even when they are aware they are part of an experiment, volunteers are generally deceived or not given full information about the purpose of the experiment. Experiments sometimes involve other “participants” who are actually confederates behaving in a realistic but specified manner in order to provoke some kind of response or decision on the part of the volunteer. Any experiment will also include at least two groups differing on a single parameter—a control and an experimental condition, in other words. Generally a single study will be part of a series, a whole research program, in which multiple experiments test numerous variations on a theme, in order to increasingly refine our understanding of a given psychological process.

Crucially, one of the keys to obtaining reliable, predictable data in psychology as in any other field of science is obtaining a large enough sample size. Thus, you recruit as many different volunteers as your grant money affords, and you run the experiment enough times that even a small behavioral difference between the conditions will achieve statistical significance and thus pass muster as a robust finding. Then, there is the need to repeat the experiment across different laboratories and replicate the finding so everyone can really trust it.

Repeatability of findings happens to be a huge problem across our sciences these days, since perverse reward incentives (tenure and grant competition, etc.) and other problems such as fraud are leading to the publication of data that are not as robust as they seem at first glance. But imagine those perverse incentives weren’t there. Imagine you were a “science machine” with all the time in the world and thus infinite patience, and with no pressure to publish or obtain tenure with startling findings, and your only goal was to acquire a truly “thick” understanding of how humans behave and react to specific circumstances with extraordinary confidence. Part of this imperative would include grasping that the species being studied is highly complex, that it is culturally and socially and psychologically adaptable and even biologically still evolving (and that your own actions may contribute, at least in a small way, to that evolution).

It would mean, I think, that you would endlessly devise new experiments to test new and different emerging hypothesis, run those experiments with large enough numbers of humans that your findings would be robust (but not so many that you ended up interfering in a significant way with the species as a whole); and it would mean that you would need to re-run the various experiments again and again and again, ceaselessly, throughout history. Many, many “landings,” in other words. As a science machine, you would be doing a lot of science, again and again, interacting just enough to test hypotheses in large enough samples, but not betraying your true purposes to the “volunteers.”

Thin Slicing vs. Deep Anthropology

As far-thinking as Vallee was (and is), he formulated his critique of the ETH at the toddler-hood of computer technology, so may have tended to think of the limits of information in human-experience rather than computer-experience terms—in other words, of isolated visits to reconnoiter and gather samples and “report back” somewhere. Carl Sagan envisioned extraterrestrial contact with earth in similar terms—periodic visits (every 10,000 years or so, he suggested). But when science can be undertaken completely by locally-based machines with storage capacities (locally or remotely) that vastly exceed even the computers of our NSA—and that are coordinated, unbiased, totally patient because they have nothing else to do and nowhere else to be, and moreover can collaborate in large numbers because they can reproduce themselves—then a level of science could probably be achieved that would be hard for any human to fathom.

One might ask why an extraterrestrial civilization would want to engage in such “deep anthropology,” but political and scientific realities of our own time make the answer pretty evident. Our scientific, technological society is already built on centuries of “basic” science—that is, science undertaken for its own sake, usually without any direct or foreseeable payoff in application. Knowing the mating habits of deep-sea protozoa may seem useless to most people (including many taxpayers who do not understand the importance of this kind of science), but scientists and smart policymakers who fund the science know that these details are all part of a big puzzle and any bit of information may ultimately pay off in unforeseen ways, years or decades or centuries down the long road. Thus, are our basic curiosity about the universe, and our social ability to invest resources in that curiosity, adaptive.

More basically, knowledge is power (or at least, security). It enables prediction and control. If money were no object, there is certainly no limit to the degree of prediction and control an intelligence agency like our NSA would like to achieve over even the remotest long-term threats to a nation’s security—for obvious reasons. As much as we may balk at the kind of surveillance our spying programs engage in, if it could be shown (and surely they will attempt to do so) that another 9/11 would be averted through such deep, extensive data collection, then some people would have no problem with the loss of privacy entailed. Likewise there is no limit to the degree of prediction and control—over illness, for example—that researchers at NIH would like to attain, given unlimited funds. If a cure for cancer can come of vast linkages of medical records and trial data, who will dispute such a project?

We thus need not even invoke any “anthopocentric” motive of pure curiosity to see why an alien intelligence or civilization will, when capable of “learning all that is knowable” inexpensively and in an automated fashion, embark on such a project. Such a civilization will have gotten to where it is through the same path we did—through science. When the kinds of constraints we now still face, in terms of funding and resources and the limits of human bias and the limits of processing power and storage, are overcome through advanced artificial intelligence and robotics, such a species/civilization will be in a position to undertake knowledge acquisition of mind-boggling scope and resolution, and it will have no reason not to.

That civilization will send its eyes and ears and roving brains outward, everywhere settling in for the long duration, in large semi-coordinated numbers, learning all that is learnable over the whole history of every star and moon and planet, about its geology and weather and even its primitive flora and fauna (if any)—because who knows what will happen in a million or a billion years? Who knows where life will emerge from primordial muck? Who knows what tree-dwelling mammal might become a spacefaring, militaristic civilization down the long road, and thus be worth settling in with and watching closely and learning how to predict and control should that species ever pose a threat to its security?

—

The Orbit of Being (Thoughts on ‘Gravity’)

Back in the day, in English class, we all learned that stories can be broken down into a few basic conflicts: Man Versus Man, Man Versus Himself, etc. The one that always seemed the least interesting to me was Man Versus Nature. You don’t really see this conflict very often. It’s really the hardest kind of story to tell and make interesting, without somehow personalizing Nature in a way that makes it unrealistic

Even stories that seem to be about overcoming nature’s destructiveness most of the time become stories of Man Versus Man, by situating the narrative within the context of human hubris or greed, for example, and complicating the story with elements of human conflict versus cooperation. Jaws, for instance, is a pretty pure Man Versus Nature story, but it couldn’t sustain its drama without the Man Versus Man elements—such as the arrogance and greed of the Amity Island mayor to keep the beaches open despite the threat, and shark-hunter Quint’s Ahab-like obsessiveness is needed to enliven the drama.

Even stories that seem to be about overcoming nature’s destructiveness most of the time become stories of Man Versus Man, by situating the narrative within the context of human hubris or greed, for example, and complicating the story with elements of human conflict versus cooperation. Jaws, for instance, is a pretty pure Man Versus Nature story, but it couldn’t sustain its drama without the Man Versus Man elements—such as the arrogance and greed of the Amity Island mayor to keep the beaches open despite the threat, and shark-hunter Quint’s Ahab-like obsessiveness is needed to enliven the drama.

The rare survival stories that avoid the Man Versus Man elements inevitably become Man Versus Himself dramas. Think of Castaway, for example. This is because it is hard not to have a bad guy, even if the bad guy must be made an aspect of the protagonist’s own character.

In his Poetics, Aristotle laid down the number-one rule that character is fate and vice versa—that what happens to a person in a story must be linked in some significant way to who they are, why they are who they are, or who they become by the time the story is over. This rule has always governed storytelling, but beginning in about the early 80s, with the rise of scriptwriting gurus who created formulas that turned Hollywood storytelling from an art into something more like a science, the relationship of character to fate became much, much more predictable.

For example, Syd Field took Aristotle’s principle and formulated what he called the “circle of being”—the idea that a character’s story arc is a continuation of some trauma or failure in that character’s backstory. It’s a good idea when judiciously applied, but most Hollywood scriptwriters aren’t judicious. Nowadays when we go to a movie, we can bet money on the fact that whatever predicament the protagonist is in is ultimately their own fault or at least linked to something they themselves did, and we can be sure that getting out of the predicament (and becoming a hero) means undoing some past mistake and learning a great life lesson in the process.

I think what people love about Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity is not just its great visuals but also its dogged resistance to tying its narrative more than minimally to anybody’s past traumas or to their growth as a person. Cuaron was clearly intent on purifying his story of extraneous, schmaltzy melodrama as much as possible. This, as much as those visuals, is what makes the story feel real.

For example, the fascinating complex opening sequence makes clear that the disaster is nobody’s fault except the Russians’ miscalculations, certainly not the fault of anything protagonist Ryan Stone did. (The merciful Cuaron even finds a very clever way to redeem the Russians: It is their Soviet-era Soyuz module that serves as Ryan’s lifeboat later.) The one thing we know about Ryan’s backstory is that she had a daughter who died, and here we may feel like we are being set up for a standard circle-of-being character arc. In fact, we are, but in a minimalistic way that undercuts any expectations that the protagonist is going to redeem herself for some past failure.

Just like the catastrophe that begins the narrative, Ryan’s daughter’s death is explicitly made by Cuaron to be nobody’s fault—she slipped and hit her head on a playground, “the stupidest thing.” In other words, her daughter, too, was killed by gravity—the dumb thing makes everything move in a straight line at a constant velocity unless struck by another thing moving in a different straight line (like a head versus the earth’s surface, or two bodies colliding in orbit). The sequential cataclysms that propel the film make vivid how perfectly mindless are the billiard-ball Newtonian principles that dominate our world. Matter in motion has no malice, no intention for good or ill. You can get infuriated and upset and scared, but there’s no one there to blame or get mad at or hate. Gravity is, indeed, rather like the sharks that ate Quint’s WWII shipmates in Jaws: It has black empty eyes, “a doll’s eyes.”

What kind of protagonist does it take, in Aristotelian terms, to face and perhaps defeat a doll-eyed antagonist like gravity? Well, precisely someone with their own unique and powerful momentum and inertia. This is the singular quality Ryan Stone possesses. She says when she learned of her daughter’s death, she just “kept driving” (and listening to the radio), from that moment forward in her life. I can’t help but feel that casting Sandra Bullock in this role—an object in motion that stays in motion—was a clever nod to Speed (with which this film bears more than a little resemblance, when you think about it). Instead of doing something different or giving up in despair, she just kept on quietly (perhaps a bit soullessly) following the specific trajectory she had at the moment she learned of the loss. She’s rather like, well, an astronaut in this respect: a bit boring, a bit lacking in the kind of emotion and drama that is typical of non-astronauts. But highly capable, ultimately resilient, and the only kind of person who could prevail in such an extreme situation.

The closest Gravity comes to replicating the standard circle-of-being formulas we’re used to seeing in movies is the scene where Ryan dreams about her lost shipmate Matt Kowalski joining her as she drifts off to her final sleep in the chilly, fuel-less Soyuz. His phantasm exhorts her not to give up, and in the process reminds her of a possibility about the Soyuz spacecraft that she had consciously forgotten. There’s a direct parallel here to a remarkable moment late in the harrowing survival documentary Touching the Void, a film that Gravity reminds me a lot of.

At climber Joe Simpson’s “lowest” moment, near the end of his horrific journey down Siula Grande with one broken leg—when he is so near the base camp he can smell his fellow climber Simon Yates’ urine (because he is crawling through it)—he finally beings to feel hopeless, because he thinks Simon has abandoned the camp. But Joe’s own brain comes to rescue in a fashion that even he, in his book on his ordeal, didn’t detect (not having read Freud, apparently): An annoying pop song, Boney M’s “Brown Girl in the Ring,” suddenly becomes stuck in his head. With the refrain, “show me your motion,” it is his own unconscious mind exhorting him to keep moving and not give up. As when Ryan wakes up in her cold capsule, realizes she’s really alone, but also realizes there’s still hope, It’s a weirdly triumphant moment.

Touching the Void is in fact the only film I can think of that rivals Gravity in its realistic intensity and lack of extraneous melodrama. Although the true story of Joe Simpson’s survival is complexified and complicated by moral conflict (Simon Yates’ controversial but necessary decision to cut the tether binding them and let Joe fall off the mountain to his almost certain death), the narrative really centers on Joe’s own dogged persistence after that point, his pure unwillingness to let the stupid elements kill him, despite a broken leg, dehydration, and a thousand other things. It’s a riveting story, and it needs no circle of being: We don’t know where in his past Joe got his overwhelming will to survive; it’s clearly just who he is. We only find ourselves wondering whether we, in the same awful boat, would find even a fraction of that quality in ourselves.

As with Joe Simpson, Cuaron’s protagonist Ryan Stone may be forced to learn about her true capacities, but she’s not undoing any past failures, the way she would be in a movie by most any other filmmaker. She’s just doing what she’s been doing ever since dumb gravity killed her daughter, which is precisely what she was doing before then too: moving forward. Is this the circle of being? Yes and no. More like a straight line in curved space, the dogged persistence of a satellite or a moon following its orbit.

Gravity’s achievement is not just its incredible visual effects but also the courage of its minimalistic storytelling: It manages to tell a truly Man Versus Nature story untainted by Man Versus Man conflict and with only the barest minimum of Man Versus Himself schmaltz to get in the way. In the hostile, airless space of today’s overblown and predictable special-effects-driven epics, it is like a breath of fresh air.

xxx

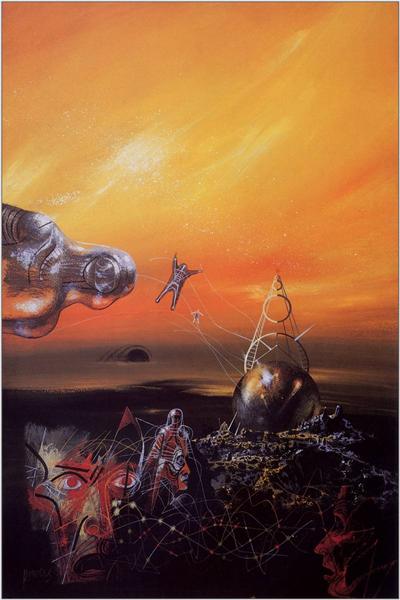

Mutants, Mystics, and Scientologists (Thoughts on Jeffrey Kripal, Gnosticism, and Sci-Fi Spirituality)

Call me a slow learner, but it took me until my early forties to realize that some of the best and most inspiring things in life, besides girls, are the things I was obsessed with as a 10-year-old boy (i.e., just before I discovered girls).

At 10, I was a typical nerdy 1970s kid, curled up with sci-fi and fantasy paperbacks when I wasn’t glued to the TV in the wood-paneled basement rec room in my corduroys watching Star Trek reruns, Space 1999, or Leonard Nimoy’s In Search Of. Later, out of some horrible, misguided sense of teenage conformity and the bogus need to “grow up,” I ended up setting aside all that, put Dune and Lord of the Rings and Star Wars and my Alien graphic novel away in a box, and took up more respectable interests like science without the “fiction” attached.

At 10, I was a typical nerdy 1970s kid, curled up with sci-fi and fantasy paperbacks when I wasn’t glued to the TV in the wood-paneled basement rec room in my corduroys watching Star Trek reruns, Space 1999, or Leonard Nimoy’s In Search Of. Later, out of some horrible, misguided sense of teenage conformity and the bogus need to “grow up,” I ended up setting aside all that, put Dune and Lord of the Rings and Star Wars and my Alien graphic novel away in a box, and took up more respectable interests like science without the “fiction” attached.

But eventually, and especially after having two UFO sightings less than a month apart in 2009, I allowed all those “immature” things to flood back in—science-fictional realms like aliens, bigfoot, ESP, and all domains of the paranormal and Fortean. I have not only taken them seriously but also made them my compass in recent years, and it has been one of my best and, frankly, most mature choices in life. To use Joseph Campbell’s overused phrase, I now, at long last, follow my bliss. (I highly recommend following your bliss, although I acknowledge that it is harder to really, authentically do than Campbell made it sound—there are so many competing pressures…)

I’ve been gratified to discover that my pre-adolescent sci-fi obsessions actually harmonize very well with my more mature and respectable interests, like Eastern religion. Meditating on the unknowable is a tried-and-true Zen technique, and meditating on alien civilizations, interdimensional beings, and the (im)possibilities of machine sentience, as well as luxuriating in the alien/future mindscapes of sci-fi artists like H.R. Giger and Richard Powers and the novels of Philip K. Dick, is as true and effective a path to Kensho as finding one’s original face or chewing the bone of “mu.” After an intense period in which I had been rereading Jacques Vallee’s Invisible College, thinking and writing about the Alien films, and also studying the collected admonishments of the 9th-century Zen teacher Lin-Chi (Rinzai), the latter master chose to burst out my chest, Alien-style, to both kill and admonish me one evening as I descended into a Maryland Metro station in the rain. It was a sweet enlightening joke that kicked me into a mildly ecstatic state for a few days. Among many other things, this experience proved to me that, if only as a line of thinking and inspiration, sci-fi and Fortean realms are truly a gnosis.

I was delighted to discover I was not alone in the impulse to seek gnosis through reclaiming my pre-/pubescent sci-fi bliss. Many of my generation seem to be discovering that the secret science-fictional surreality behind the unreasoning mask of consensus reality is where it’s at, philosophically and spiritually. Jeffrey Kripal, professor of Religion at Rice University, is a scholar of this trend, and his most recent book, Mutants and Mystics

, concerns mystical experiences and how they nurtured 20th century imaginative literature and comic books. Even when I was a kid, there was something undefinably holy to me about the best science fiction (such as Alien), and Kripal effectively illuminates what that holy thing always was.

Dick, Gnosis, and Human Potential

I encountered Kripal’s Mutants and Mystics about the same time I was delving into the newly published, massive Exegesis of Philip K. Dick. who happens to be one of the case studies in Kripal’s book (Kripal also served as one of several editors on Exegesis). Dick famously had a mystical/ecstatic experience that spanned several months in the early 70s and served as the compass of his life thereafter. He devoted thousands of journal pages (the Exegisis itself) as well as a trilogy of novels (beginning with VALIS) to accounting for and making sense of this experience. Triggered initially by dental anesthetic and possibly also megadoses of vitamins, his experience followed a familiar pattern in the annals of religious experience: feeling “zapped” by an energy beam, which opened overwhelming floodgates of information and awareness about everything from a then-unknown but potentially fatal birth defect in his son (then confirmed by a doctor) to the spiral structure of time and reality. (Fans of entheogen prophet Terence McKenna should read the Exegesis and see if it doesn’t remind them uncannily of McKenna’s near-contemporaneous Amazonia experience, down to their independent parallel insights about the structure of time.) If you feel unprepared to tackle the 900-plus page Exegesis, R. Crumb depicted the gist of it, graphically, in a few pages.

Although Dick regarded this experience as enormously important in his life, it also baffled him and was not without its outrageously paranoid and fearful dimensions. The “familiar pattern” it followed was that of traditional capital-G Gnosticism—the basic insight of which is that our ordinary world is an illusion sustained by a malevolent intelligence that is at odds with the higher, “good” creative or loving force in the universe. Although there were many ancient Gnostic sects with different views, they by and large saw the consensual world we live in as a deception perpetrated by a malevolent demiurge—the God of Genesis who badly wanted Adam and Eve not to eat the apple of gnosis in the Garden of Eden and who punished them for doing so. The real Creator, Gnostics have always felt, wouldn’t behave that way.

Christianity has been riven from the start by the conflict between institutionalized faith and direct experience (gnosis) of the divine. The faith side has always prevailed outwardly—the first coup being the excision of the numerous early Gnostic texts from the canon when the Bible as we know it was compiled in the 2nd century. Branding the whole personal-experiential side of Christianity as heresy was an important and necessary strategic move to ensure the Church’s institutional growth and spread, according to Elaine Pagels. Yet the lingering dissatisfaction with second- and third-hand experience (i.e., “faith”) would perpetually generate backlash movements and revivals, such as Catharism in Medieval France and then the Protestant Reformation, as well as various newer, American-born movements that have all been aimed at getting back to direct personal experience of the divine, bypassing worldly priestly middlemen and faith-based dogmas. The self-avowed Gnostic literary critic Harold Bloom wrote a few excellent books about these movements back in the 1990s, and Kripal seems to be following in that Gnostic-critical tradition with his studies of science fiction and the paranormal. (Bloom himself clearly detected a sci-fi-Gnosticism link, having been obsessed with and even writing a sequel to David Lindsay’s bizarre Gnostic allegory A Voyage to Arcturus.)

One of the strange and ambiguous directions sci-fi Gnosticism leads into is the human potential movement—which I was also sort of steeped in during my teenage years, being both a child of psychologists and a voracious teen reader with little chance of having an actual girlfriend. Kripal shows that sci-fi and comic books’ obsession with extraordinary powers is linked closely to the concerns of real-world self-help gurus, parapsychologists, remote viewers, and the types of people who founded and visited Esalen during its heyday in the 1970s. There is a shared sense through these various marginal realms of writing and research that humanity is on the brink of a new transformation in our evolution. The sense is that we are moving toward an X-men-like world of “mutants” living quietly in our midst and possessing an arsenal of Fortean “wild talents.”

One of the strange and ambiguous directions sci-fi Gnosticism leads into is the human potential movement—which I was also sort of steeped in during my teenage years, being both a child of psychologists and a voracious teen reader with little chance of having an actual girlfriend. Kripal shows that sci-fi and comic books’ obsession with extraordinary powers is linked closely to the concerns of real-world self-help gurus, parapsychologists, remote viewers, and the types of people who founded and visited Esalen during its heyday in the 1970s. There is a shared sense through these various marginal realms of writing and research that humanity is on the brink of a new transformation in our evolution. The sense is that we are moving toward an X-men-like world of “mutants” living quietly in our midst and possessing an arsenal of Fortean “wild talents.”

To his great credit, Kripal takes all this very seriously. He is essentially spreading an incredibly liberating (if you were once a 10-year-old boy) gospel that our teenage sci-fi intuitions about our hidden capabilities were all true, and we should embrace them and actually take them seriously and learn to apply them in life. As an academic, he has to discuss all this in scholarly, heavily-footnoted way, but he doesn’t try too hard to curb his personal enthusiasm. He wants to move these transmutative experiences and wild talents out from the furtive seclusion of an easily disregarded literary ghetto and awaken us to their actuality and their potency in the real world. He clearly agrees with and, I am sure, participates actively in, this self-transformatory agenda (his many hints about Tantra, and the fact that he apparently spends a lot of time at Esalen, are clues to his own self-transmutative priorities).

I’m right on board (minus the Esalen): There’s a lot more in heaven and earth and in our own mental capacities than is dreamt of in consensus reality. The kinds of things the Mentats and Bene Gesserit did in Dune?—these are all achievable skills. People can and do achieve even weirder things that mainstream science can’t explain and doesn’t want to acknowledge, and you can find guides to these capacities if you pay attention to marginalized literatures, Renaissance Hermeticists, Eastern practices, and 70s self-help paperbacks in used bookstores, and (in some cases) do a little creative reading between the lines. Direct insight into the workings of cosmos and mind are possible to everyone, with a little discipline—just becoming aware of the methods available is the first step. It’s a whole new world.

(Submessage: Start meditating, or doing Tantra; start practicing lucid dreaming and recording your synchronicities; learn about and practice the ancient mnemonic arts; read up on remote viewing and Psi research; etc., etc., right now—you are wasting your life and your mind on TV trivialities if you don’t.)

The Big But

As fascinating and cool as higher states of consciousness and the cultivation of our dormant potentials can be, there is a dark, paranoid as well as elitist aspect of big-G Gnosticism that typically gets downplayed in modern attempts to reawaken interest in this ancient strand of thinking.

From Carl Jung to Pagels to Bloom and now Kripal, the emphasis tends to be on small-g gnosis (the Greek word for wisdom or intuition)—that is, personal direct experience of higher, divine reality. This part is all well and good, but it is not unique to big-G Gnosticism, being shared by many other wisdom traditions both Eastern and Western. What defined many ancient big-G Gnostic sects is the further sense that our entrappedness in the material consensual world is the product of an ancient conflict between lesser and higher divinities. The Gnostics were those “in the know” about this secret state of affairs. In their view, the public myths and doctrines of mainstream religion (and in our age, science) are part of a deceptive conspiracy on the part of a lesser god, trapping and limiting the imagination of humanity and thereby disempowering or even enslaving us. If it sounds like The Matrix, well, that’s exactly what it is. The Matrix is a modern Gnostic myth.

There’s an important distinction to be made here, between seeing consensus reality as error or ignorance and seeing it as the product of somebody’s (or some thing’s) willful effort to pull the wool over our eyes or entrap us. Failure to draw this distinction has led a lot of writers toward confusion on what Gnosticism is and how it differs from other wisdom traditions.