When Is It Hyperfootball Season?—Rethinking Eternalism

There are rumblings from the Internet that graphic novelist and magus Alan Moore is soon to drop a million-word novel on the world, called Jerusalem. It shows great courage and faith, in a world that no longer reads books, that Moore has stretched out his text as much as possible instead of compressing his ideas to the size of a tweet, which is the direction most people are going in. It sounds interesting. In an interview in Aeon magazine, Moore dazzles the interviewer Tim Martin with the novel’s central theme, eternalism:

In essence, eternalism proposes that space-time forms a block—‘imagine it as a big glass football’, Moore suggests—where past and future are endlessly, immutably fixed, and where human lives are ‘like tiny filaments, embedded in that gigantic vast egg’. He gestures around him at the rubbish-strewn path, his patriarch’s beard waving in the wind. ‘What it’s saying is, everything is eternal,’ he tells me. ‘Every person, every dog turd, every flattened beer can—there’s usually some hypodermics and condoms and a couple of ripped-open handbags along here as well—nothing is lost. No person, no speck or molecule is lost. No event. It’s all there for ever. And if everywhere is eternal, then even the most benighted slum neighbourhood is the eternal city, isn’t it? William Blake’s eternal fourfold city. All of these damned and deprived areas, they are Jerusalem, and everybody in them is an eternal being, worthy of respect.’

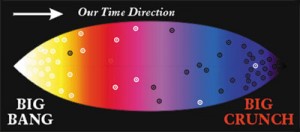

The notion is that, if we could step outside of our puny three-dimensional Now and see all of cosmic history at once, we could see how every particle in the cosmos has a world line extending from one end to the other, dividing and interweaving and then recombining. We can imagine sliding back and forth along our own world line into the past and future, like scrubbing the cursor back and forth in a video-editing timeline, because everything from the Big Bang to the Big Crunch (the two tips of Moore’s football) is permanent.

But is permanence the only reason something is worthy of respect? Is a slum the same as Jerusalem only if it persists eternally? This was Nietzsche’s idea with his notion of Eternal Recurrence: Things matter, assume some kind of ontological substantiality, if they repeat endlessly. Nietzsche’s thought experiment was also the theme of Milan Kundera’s great novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being: If there is no repetition or permanence, life is like a sketch that is never filled in. Impermanence is a notion that can drive some to despair; some would say that if they only happen once, then they might as well not have happened at all (which is why Kundera described it as “unbearable”).

But is permanence the only reason something is worthy of respect? Is a slum the same as Jerusalem only if it persists eternally? This was Nietzsche’s idea with his notion of Eternal Recurrence: Things matter, assume some kind of ontological substantiality, if they repeat endlessly. Nietzsche’s thought experiment was also the theme of Milan Kundera’s great novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being: If there is no repetition or permanence, life is like a sketch that is never filled in. Impermanence is a notion that can drive some to despair; some would say that if they only happen once, then they might as well not have happened at all (which is why Kundera described it as “unbearable”).

I don’t agree. I like Alan Moore a lot, but whenever I read anything by him (even an interview), I get the weird sense I’m in the presence of a hoarder. (Am I the only one who has this feeling?) While the concept of eternalism is appealing on one level, I think it’s also a very cramped, claustrophobic model of time and ethics that actually precludes anything truly interesting from happening in the universe—including phenomena that Alan Moore fans themselves enjoy, such as synchronicities and magic. It also doesn’t really leave any breathing room for consciousness or free will.

I’d suggest that spacetime is much weirder and more interesting than a football, and that respect for every stray beer can and syringe—not to mention every person or animal—is perfectly possible even if they don’t last.

Trapped in Amber

A solid glass-block universe, which was originally formulated by Einstein’s teacher Minkowski in 1908, is one in which the crude truism about the impossibility of killing your own grandfather—or, more subtly, altering the course of a single particle in a butterfly-effect universe—holds sway. In such a universe, linear causality is ironclad, and thus it is implicitly materialistic and deterministic.

It is some vague notion of the glass football, where everything is eternally preserved like flies in amber, that prevents materialist hard-liners from ever accepting the possibilities suggested by various paranormal phenomena like precognition, which necessitate that information can in some form travel from the future into the past and affect the unfolding of events. Such experiences, even if they are seldom actually useful, are too numerous in our lives and too well-attested even in scientific research to deny. (Having lately taken the ‘J.W. Dunne challenge’ and systematically scrutinized my own dream life for fine-grained evidence of precognition—and not only memory encoding—I am now even more persuaded that our relationship to time is way more complicated than our commonsense models of causality admit.)

The multiverse theory that physics increasingly allows as a loophole in these rules isn’t very satisfying: Instead of an actual alteration of history, any deviation from the glass football just spawns a new, different glass football. If you go back or make some alteration in the crystalline spacetime structure, you are actually giving birth to a new universe with an altered history, not affecting the original one. If you go back and time and kill your Grandfather, in other words, it does not produce a paradox because you have actually killed an alternate-universe Grandfather and not the one from your origin universe; likewise, information from the future in a precognitive dream would actually be information from a different future, and thus highly suspect.

But the main problem is, the four-D glass football does not include the knower in the known—who’s the guy holding the football? Where is he? When is he? In a glass football universe, the consciousness of anyone venturing back along the timestream to collect or recollect one of those beer cans (along with everyone else’s consciousness and indeed every material configuration, the position of every particle) would itself “travel” back in time, making the whole notion of travel meaningless—merely an idea in somebody’s head at a particular point in time, a pure fiction or metaphor with no basis in reality. The very idea of the glass football becomes meaningless if there is a single temporal dimension, because there is no external vantage point from which to even verify its truth or falsity.

Eddies in the Space-Time Continuum

“Time is a sphere, and I have been reincarnated in the same time at which I exist!” —Bachman, Silicon Valley

Many physicists would now say that there are more dimensions than the ones we’re aware of. Even if space itself isn’t as voluptuous as we may think (as I suggested in my post on anamorphosis), there may be more than one temporal dimension. If there is even just a second dimension of time, then the glass football suddenly becomes a hyperfootball, and all bets are off.

A hyperfootball is much more interesting than a football, any day of the week, even on Sunday. First of all, history may spiral back and intersect and interpenetrate itself in all kinds of ways that are impossible to visually represent. If there are three temporal dimensions, history could even have volume. A looping, thick, or even turbulent historical/causal stream would produce some very strange effects and phenomena, things appearing to defy our expectations of causality. A “tesseract” such as that depicted in the movie Interstellar is just one possible way of imagining the possibilities.

A hyperfootball is much more interesting than a football, any day of the week, even on Sunday. First of all, history may spiral back and intersect and interpenetrate itself in all kinds of ways that are impossible to visually represent. If there are three temporal dimensions, history could even have volume. A looping, thick, or even turbulent historical/causal stream would produce some very strange effects and phenomena, things appearing to defy our expectations of causality. A “tesseract” such as that depicted in the movie Interstellar is just one possible way of imagining the possibilities.

There could be Douglas Adams’ famous “eddies in the space-time continuum.” Event-streams could move at an angle to ours, intersecting obliquely or perpendicularly, semi-overlapping. History could even become “frothy” if the temporal flow becomes turbulent rather than laminar. In the folds or froth, where our limited sensory apparatus detects multiple converging time streams, we might encounter “flickers,” glitches in the matrix, synchronicities, and multistable phenomena—either/or or both/and structures, about which no two witnesses would agree. Sound familiar? People could reincarnate into the past, or even into the present (like Silicon Valley’s Bachman).

We might even experience a sense of living in two times at once.

The latter was precisely the experience Philip K Dick had in the mid-1970s and that forms the basis for his 900+ page Exegesis, surely now the touchstone (or capstone) text for any sci-fi Gnostic cosmology. After seeing a gleaming Jesus fish around the neck of a young woman delivering pain medication to his house after a tooth extraction, he began to download information ranging from the factual (such as an undiagnosed but potentially fatal birth defect in his son) to the cosmological (such as insights into the spiral structure of time and reality). Historical configurations or events repeated, albeit with an altered appearance: Specifically, the writer became certain that the America of gas shortages and the fall of Nixon was a replay of apostolic Rome, and that Gnostic Christians were once again circulating in secret, communicating with covert symbols (i.e., the fish), and awaiting the redeemer.

The latter was precisely the experience Philip K Dick had in the mid-1970s and that forms the basis for his 900+ page Exegesis, surely now the touchstone (or capstone) text for any sci-fi Gnostic cosmology. After seeing a gleaming Jesus fish around the neck of a young woman delivering pain medication to his house after a tooth extraction, he began to download information ranging from the factual (such as an undiagnosed but potentially fatal birth defect in his son) to the cosmological (such as insights into the spiral structure of time and reality). Historical configurations or events repeated, albeit with an altered appearance: Specifically, the writer became certain that the America of gas shortages and the fall of Nixon was a replay of apostolic Rome, and that Gnostic Christians were once again circulating in secret, communicating with covert symbols (i.e., the fish), and awaiting the redeemer.

To explain this overlapping or confluence of eras, Dick attempted to think four-dimensionally about space and time, much in the vein of Moore’s eternalism, invoking Minkowski’s solid-block spacetime, but quickly he realized that four dimensions are not enough to contain the universe as he experienced it. At least five are needed. It is precisely this fifth dimension, perpendicular to the fourth, that contains the redemptive potential of the universe. But in doing so, I argue, it implicitly calls into question the permanence of every stray condom and syringe in the gutter of Moore’s Jerusalem.

The Fifth Dimension

From the standpoint of the fifth dimension, the fourth (linear time) becomes just an additional spatial dimension, perpendicular to the other three—precisely as Einstein said—but the fifth becomes a Platonic dimension of meaning or form. Early in his voluminous musings, Dick compares history to a kind of printer or typewriter (implicitly the then-popular IBM Selectric, as one of the editors notes), with this orthogonal dimension a rotating ball or a print head sliding back and forth printing out Platonic forms on the unfolding paper of history. In a much earlier era, the metaphor might have been one of warp and weft, with history as the tapestry that results from this interplay of Time and (eternal) Form—enabling a tapestry to actually show a picture, not just be rainbow-like rows of meaningless color.

Although Dick toys with a million different theories and riffs on his core neo-Platonic cosmology in various ways across the eight-year span of the Exegesis, he eventually seems to converge on an even stranger view: that basically, there is no single history, and that certain objects or configurations—what he calls “common constituents”—do not recur so much as never alter, and thus become foci of an eternal present persisting amid change. At least, that’s how I interpret some of the late entries in his notebook. In early 1982, shortly before his death, he wrote:

Although Dick toys with a million different theories and riffs on his core neo-Platonic cosmology in various ways across the eight-year span of the Exegesis, he eventually seems to converge on an even stranger view: that basically, there is no single history, and that certain objects or configurations—what he calls “common constituents”—do not recur so much as never alter, and thus become foci of an eternal present persisting amid change. At least, that’s how I interpret some of the late entries in his notebook. In early 1982, shortly before his death, he wrote:

In this fifth dimension time, things are ‘now’ if they possess a common constituent; viz: ‘now’ signifies any and all of our fourth dimensional worlds where such a common constituent … is; … in a five dimensional world, that golden fish sign was in USA 1974 and Syria A.D. 70 simultaneously.

In other words, “common constituents,” the way Platonic ideal forms manifest in the physical world and history, give a secret structure to Time as points where the forward movement breaks down and becomes an eternal present. They are islands of permanence in a temporal river that slows down or develops eddies in their vicinity, almost like a viscous Heraclitean river with Parmenides (or perhaps several Parmenides, plural) standing defiantly out in the middle of it.

In Dick’s five-dimensional world, there would be no uniform time stream, but a gradation. Things would be shimmering and contradictory and fleeting at the periphery, but things would get more permanent the closer you get to the sublime common constituents—the zone of what might be called “grace.” Indeed isn’t there a similar tension in mainstream Christian doctrine? At the end of time, the important stuff—namely, people, or perhaps some broadened conception of humanity—is resurrected, brought back from oblivion, but the bad stuff that happened (sin) is washed away or redefined, implying a sort of cleansing of Jerusalem’s gutters.

Nostalgia for the Impossible

Events from the future do appear in my dreams, but Jerusalem has not manifested itself on my dream bookshelf, so my musings here can hardly or fairly stand as a review of that book or Moore’s ideas. But the glass football of eternalism strikes me as fundamentally a claustrophobic, hoarder’s universe, in which the price of keeping every speck or molecule is a lack of freedom to move or to breathe. The universe strikes me as being far more weird, contradictory, and incomplete than that.

If history isn’t purely linear, then the future can affect the past—or the eternal lockstep march of time may be entirely an illusion, as indeed Einstein’s relativity theory sort of predicts: History is not exactly the same from any two points in space, even on the subatomic level. If that’s the case, there’s no single configuration of anything; history is a swirling, shimmering, flickering mess of contradictions and folds, where possibilities including stray beer cans or dog turds either are or aren’t depending on where you stand in relation to them. More importantly, determinism isn’t, well, deterministic; there’s space for free will, as well as space for consciousness that isn’t a pure fiction or emergent property of molecular-cellular interactions.

If history isn’t purely linear, then the future can affect the past—or the eternal lockstep march of time may be entirely an illusion, as indeed Einstein’s relativity theory sort of predicts: History is not exactly the same from any two points in space, even on the subatomic level. If that’s the case, there’s no single configuration of anything; history is a swirling, shimmering, flickering mess of contradictions and folds, where possibilities including stray beer cans or dog turds either are or aren’t depending on where you stand in relation to them. More importantly, determinism isn’t, well, deterministic; there’s space for free will, as well as space for consciousness that isn’t a pure fiction or emergent property of molecular-cellular interactions.

The five-or-more-dimensional universe where history shifts and shimmers—the universe of the impossible—is radically susceptible to alteration and change, and to gnosis. It includes a space for the knower.

Think about it: Which is more important to you, your freedom or the ability to go back and recover every lost beer can? While it’s a nice idea to want to commemorate everything and to think it’s all still there somewhere, somehow, it’s only impermanence that opens a space not only for free will and consciousness but also (I would suggest) true compassion. Without the shimmering space between the is and the was and the might have been, the universe would be claustrophobic and hyper-determined.

Impermanence (or more radically, impossibility) can indeed be physically painful to accept. It can feel unbearable … but so can stubbing your toe—for the first few seconds. But it’s not really unbearable. Once you push through the discomfort, it can also make things beautiful in a new way. In Zen-steeped Japan they have a term, mono no aware, for a sort of “nostalgia in the moment,” an elegaic mood that savors the passing away of things even as they are happening. I don’t know if there’s a word for a kind of nostalgia for things that don’t exist at all, a nostalgia for the impossible, but there should be one of those too.

I think it’s shortsighted to require permanence and eternity in order to respect everything that happens and passes away. It makes our respect (or compassion) that much more noble, I think, if it and its objects are ultimately unrecorded and unrewarded, and maybe even unreal. We respect them anyway. That’s our superpower as humans.

Sorry to give a “Forrest Gump” response but I suggest “both are happening at the same time”. Although “at the same hypertime” would be a more accurate way to describe it.

Moore is correct that at any given (hyper)moment of observation the big glass football is in effect and that every grain of sand or burger wrapper has an eternity to define it beyond its tiny window of normal appearance in our little 3d apetures. However PDK is correct that there is flux and flow and that things shift and change. Maybe we need to carve the big glass football into Tolkien’s Arkenstone with millions of facets. So while remaining stable in a sense, the slightest change in (hyper) perspective will cause observable variations. And when you pause to look from that new (hyper) perspective everything is different, even the seemingly eternal past and future of that perspecive.

Also there may be other layers to this effect but that are difficult to describe, hyper observation is the point and maybe that doesn’t really solve anything except which layer of the cake you are on.

PS – just found you through a comment you made at The Secret Sun and very happy to have found your site.