The Solaris Mind: Hypnagogia, Meditation, and Insight

A classic motif in science fiction is that humanity ventures to the farthest reaches of space only to find, impossibly, something of our own that we had forgotten. Stanislaw Lem’s 1961 novel Solaris, about a planet covered by a viscous ocean that manufactures simulacra from its observers’ unconscious, is probably the purest expression of this idea.

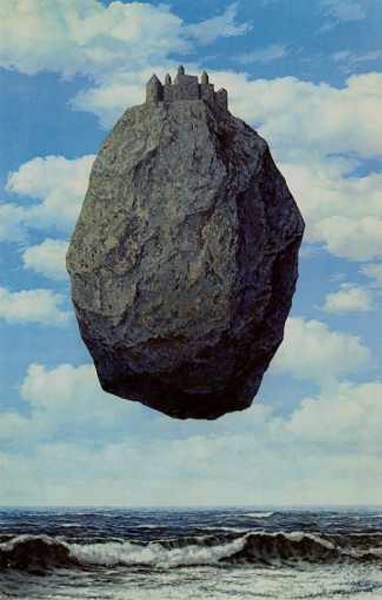

The backstory of Lem’s novel is that the planet Solaris captured the interest of its discoverers because of its impossible stable orbit around its double star. Exploration revealed that its ocean somehow, perhaps sentiently, shifted the planet’s center of mass to steer it in its orbit. But even more mysteriously, it generated beautiful sculptural forms, rising high into the atmosphere and then dissolving back into it a few hours or days later. This ocean seemed dimly and inscrutably intelligent, so a station was placed in orbit to observe and study it. After several decades of study, spawning a whole library of inconclusive research and scientific controversy, some of the forms generated by the ocean started to resemble human tools and objects, as though pulled from the memories of the scientists observing it. One scientist reports seeing a giant baby rise above the waves out of the fog, but most of his colleagues think he is crazy.

When the protagonist Kris Kelvin arrives on the station to investigate a suspected breakdown among its small crew, he finds that synthetic people from the scientists’ pasts have started to appear on the station, confronting them with their own darkest desires and painful regrets, driving them to the brink of madness—and one even to suicide. Soon after his arrival, a perfect simulacrum of his ex-wife Rhea, who had committed suicide after he cruelly abandoned her years earlier, appears in his quarters, without any memory of how she got there.

Solaris has been adapted twice for the screen—by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1972 and by Steven Soderberg in 2002. Both adaptations concentrate on the ambivalent romance that develops between Kelvin and his resurrected ex, largely ignoring the planet itself and its mimetic ocean-forms. This is unfortunate (and it disappointed Lem too), because Solaris the planet is one of the most fascinating and awe-inspiring creations in science fiction.

Solaris has been adapted twice for the screen—by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1972 and by Steven Soderberg in 2002. Both adaptations concentrate on the ambivalent romance that develops between Kelvin and his resurrected ex, largely ignoring the planet itself and its mimetic ocean-forms. This is unfortunate (and it disappointed Lem too), because Solaris the planet is one of the most fascinating and awe-inspiring creations in science fiction.

Lem, who died in 2009, remains unsurpassed in his imagining of the possibilities of alien intelligence and human incapability to interpret or understand it. With Solaris, I have no doubt the Polish writer was inspired by the most alien form of our own human intelligence: hypnagogia, the baffling and surreal imagery generated by the unconscious that can be seen clearly on the edge of sleep and in meditative states.

Digesting the Now

Hypnagogic imagery have no doubt inspired art and religion since the dawn of humanity. It was an early scientific observer of hypnagogic phenomena, the psychoanalyst Herbert Silberer, who first noted that these images are often or perhaps always “autosymbolic”—they represent, usually in an astonishingly clever way, some immediate thought or some preoccupation right now, right at the instant they are created. Like dreams, this correspondence to real experience is not immediately obvious but reveals itself readily in free-associative interpretation. I’ve argued elsewhere that dreaming is the punny, playful-associative “art of memory” operative during sleep; hypnagogia is a waking window onto this same process.

Meditators and yogis have always compared the mind to an ocean, in which thoughts are like waves that trouble the surface. I think the playful, ingenious, autistically inscrutable Solaris ocean is an even better, more nuanced metaphor than any dumb old Earth ocean. The mind is a constant mimetic sea, perpetually generating imaginary representations of everything we encounter and think about and experience; it combines and shapes these ghosts effortlessly into brilliant symbolic tableaux and scenes that brilliantly distill the meaning of “gist” of our experience. Hypnagogia shows us this automatic process, the Solaris mind’s constant metabolism of experience.

Meditators and yogis have always compared the mind to an ocean, in which thoughts are like waves that trouble the surface. I think the playful, ingenious, autistically inscrutable Solaris ocean is an even better, more nuanced metaphor than any dumb old Earth ocean. The mind is a constant mimetic sea, perpetually generating imaginary representations of everything we encounter and think about and experience; it combines and shapes these ghosts effortlessly into brilliant symbolic tableaux and scenes that brilliantly distill the meaning of “gist” of our experience. Hypnagogia shows us this automatic process, the Solaris mind’s constant metabolism of experience.

We ordinarily don’t discern or detect this continual churning out of image-representations because it is so subtle, so in the background. It is only when the foreground stuff of conscious mental chatter and active thinking is quelled or silenced that it becomes apparent. Meditators interested in the phenomenon can learn to stabilize the edge state on the verge of sleep where these forms can be witnessed and recorded. Hypnagogia can be used to access lucid dreams (the “wake-induced lucid dream” or WILD method described by Stephen LaBerge); and many consider the hypnagogic mind to be uniquely receptive to psychic phenomena. (The most comprehensive book on the topic is the wonderful Hypnagogia, by Andreas Mavromatis—highly recommended.)

But the fact that we mainly detect our preconscious image-building on the edge of sleep should not lead us to believe that it only happens then. This function, an aspect of what Sartre and Lacan both called “the Imaginary,” is a constant process, one that is essential to thinking and the associative bundling of experience so that it can feed our memory mill.

Symbolically metabolizing experience by reducing it to cartoon-dioramas firstly creates mental objects that can be fastened with symbolic labels and manipulated in thought, like toys and action figures we move around in our mental sandbox. They are a basic requirement for thinking. And because they are minimally detailed, these cartoon replicas probably maximize the amount of experience that can be fit into the limited workspace of our working memory: We can only keep 4 or 5 discrete “items” in our heads at one time.

The dioramas of the Imaginary thus facilitate the present situation forming a “chord” with immediate past and future experiences, giving thickness and substantiality to the Now. And by reducing experience to something sketch-like, they likely enable more of that experience to get through the working-memory bottleneck to be stored and transferred to long-term memory later on. The reduced, cartoon-like symbolic representation that can be unpacked at the other end, so to speak, through webs of associative linkages, just like dreams (which, I argue, are long-term memories in the process of formation—see below).

“Every thing fits into its own shape”

The Solaris mind’s incessant brilliant mimesis, as crucial as it is for functioning in the world and enabling us to remember our experiences later, is also to blame for the foremost obstructions of spiritual vision: the arising of the idea of self, and with it the constant fading of presence (that is, “being here now”) that has been the bane of meditators and mystics for millennia.

To free us from having to give all our attention to the present moment, the imagination constantly replaces our naked awareness of the world with sketch-like scenes of “I seeing.” You can experience this yourself: Just take a deep breath, exhale, and focus visually on an object in front of you. Initially there is a silent vivid sense of full presence with the object—the object richly and brightly fills your attention—but after just a few seconds the vividness of the object fades slightly as a faint, subtle mental diorama of “me seeing this” emerges in your awareness to compete with it; you might also notice further layers of imagination, like a background meta-awareness of “being seen seeing” (the constant inner haunting presence that Lacan called “the Gaze”). Naked awareness is thus perpetually obscured in consciousness with new virtual ghost-representations—literally, every few seconds, new puppet-subjects and new gazes form, in a slow but incessant pageant of simulacra that represent the self.

To free us from having to give all our attention to the present moment, the imagination constantly replaces our naked awareness of the world with sketch-like scenes of “I seeing.” You can experience this yourself: Just take a deep breath, exhale, and focus visually on an object in front of you. Initially there is a silent vivid sense of full presence with the object—the object richly and brightly fills your attention—but after just a few seconds the vividness of the object fades slightly as a faint, subtle mental diorama of “me seeing this” emerges in your awareness to compete with it; you might also notice further layers of imagination, like a background meta-awareness of “being seen seeing” (the constant inner haunting presence that Lacan called “the Gaze”). Naked awareness is thus perpetually obscured in consciousness with new virtual ghost-representations—literally, every few seconds, new puppet-subjects and new gazes form, in a slow but incessant pageant of simulacra that represent the self.

By “self” I don’t just mean the ego or “I” in the diorama. Every object of perception too, by being copied in the imagination, assumes a virtual ghost presence or double. Whenever our eyes fall on an object, this interplay of the ghost-making Solaris mind and the webs of linguistic symbols we map onto those image-representations produce the sense of recognition, a sense of “what it is,” enabling a labeled image-object to be manipulated in thought. This “what it is,” or itself-ness, the fiction of self-identity, is—when we become attached to it or believe in it—the ultimate stumbling block toward spiritual liberation. Belief in the self is the basic error and even absurdity that, for Buddhists, is the fundamental reason for human suffering.

The reason an object’s self-identity is absurd was explained best, I think, by Ludwig Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations:

“A thing is identical with itself.”—There is no finer example of a useless proposition, which yet is connected with a certain play of the imagination. It is as if in imagination we put a thing into its own shape and saw that it fitted. (We might also say: “Every thing fits into itself.” Or again: “Every thing fits into its own shape.” At the same time we look at a thing and imagine that there was a blank left for it, and that now it fits into it exactly.) Does this spot O “fit” into its white surrounding?—But that is just how it would look if there had been a hole in its place and it then fitted into the hole…

So, in short, the Solaris mind takes the alive Heraclitean flux of experience and constantly copies and fossilizes it in cold dead representational dioramas suitable to be thought about and metabolized in memory. The battle of meditative engagement is with this continuous force of autosymbolic imagining (not just the more obvious verbal chatter). The aim is not to obliterate our mental models of ego and self—we need these illusions to function in the world—but to shift the balance: from living completely in the empty, frustrating world of mental representations (images and words) toward abiding for greater stretches of time in the wordless, imageless, blissful Real that lies beyond and outside them.

The Solaris Mind Produces Teachers

During the day, because its imagery is so yoked to the senses, the Solaris mind generates innocuously realistic images that are hard to detect, because they so closely resemble the “shape” of our lived experience and then are immediately washed away by the thoughts that are seeded from them—like ocean waves erasing a picture drawn in the sand. When liberated from thought and sense, however, as on the edge of sleep or in meditation, these images assume their more wildly imaginative genius.

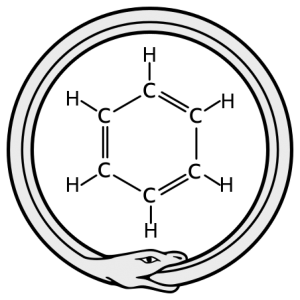

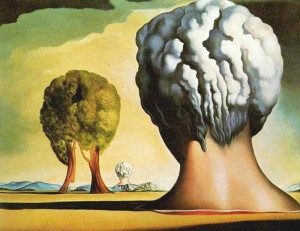

The paradoxical effect of withdrawing from the senses and temporarily quelling the flow of verbal and imaginal thought is that it enables daytime hypnagogic images to assume the vivid otherness of full-on waking dreams. These brief visions, flickering out as quickly as they appear, provide “object lessons” that can enlighten and inspire. Famously, artists like Dali have used them for inspiration. August Kekule’s famous “dream” of a snake biting its tail, which gave him the idea of the benzene ring, was actually a waking reverie, a hypnagogic image. When David Lynch

The paradoxical effect of withdrawing from the senses and temporarily quelling the flow of verbal and imaginal thought is that it enables daytime hypnagogic images to assume the vivid otherness of full-on waking dreams. These brief visions, flickering out as quickly as they appear, provide “object lessons” that can enlighten and inspire. Famously, artists like Dali have used them for inspiration. August Kekule’s famous “dream” of a snake biting its tail, which gave him the idea of the benzene ring, was actually a waking reverie, a hypnagogic image. When David Lynch writes of finding his great creative solutions in the period right after dipping into the “unified field” during Transcendental Meditation, hypnagogia is probably what he is referring to.

Buddhist orthodoxy counsels that meditators should ignore these beguiling hypnagogic images (called makyo), but here the ancient and modern masters are quite mistaken, I believe. When properly disciplined and observed with detachment, hypnagogia can be enormously helpful to a personal spiritual path.

One of my first “kenshos” as a beginning Zen meditator many years ago involved a vivid hypnagogic vision of the exact absurdity addressed by Wittgenstein with his notion of a spot fitting into its own shape. After sitting on the sofa meditating for about 15 minutes, I happened to glance down at my coffee mug, and I saw the curved handle not as something for holding the object but as a tube through which circulated the mug’s “self-ness,” flowing out and back into it, like its secret lifeblood.

One of my first “kenshos” as a beginning Zen meditator many years ago involved a vivid hypnagogic vision of the exact absurdity addressed by Wittgenstein with his notion of a spot fitting into its own shape. After sitting on the sofa meditating for about 15 minutes, I happened to glance down at my coffee mug, and I saw the curved handle not as something for holding the object but as a tube through which circulated the mug’s “self-ness,” flowing out and back into it, like its secret lifeblood.

In a flickering instant, I then grasped that every other object, and even me, would, if we actually had selves, need some kind of tubular circulatory system, like a coffee mug handle, to pump this linguistic fiction out and back in. (I was reminded, among other things, of the surreal scene in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil when the repairman played by Robert DeNiro opens up an apartment HVAC unit and “operates” on the bloody organs inside.) As this absurd idea of the self as an alive vitality inside inert objects vanished, it left in its wake a euphoric clear perception of what the Zen writers call “suchness”—things just as they are without any unnecessary concept like “self” added to them. My ordinary error of believing in things’ inner selfhood seemed delightfully absurd, and I think I grinned rather uncontrollably for a few hours afterward. (This experience, I should add—like countless subsequent ones—was brought on without the use of any substance … well, besides caffeine.)

Catch and Release

In his essay “Negation,” Freud wrote that absence can only reveal itself as the absence of a presence, and a thing has to be asserted before it can be denied. This is possibly one of his keenest insights, with implications well beyond psychotherapy. It is impossible for the mind to represent the non-existence of something; it can only show a thing along with some sign of erasure, such as the thing being destroyed, being taken away, or even being ridiculed or insulted.

In my “coffee mug” example, the Solaris mind was giving me a push. It could not directly represent for me the Zen truth of nothingness or Void or no-self; instead, at the precise moment I needed it, it showed me “self” as a kind of silly cartoon “bodily fluid” and invited me to laugh at the notion.

An active, philosophically engaged meditation practice produces such hypnagogic object-lessons quite frequently, often with the mild euphoria of an “aha” experience, and sometimes much more. In other words, meditation can powerfully open the doors of the brain’s endogenous ‘entheogenic’ capacities.

Because these kinds of insights produced by the Solaris mind are so profound and rewarding, the temptation is always to cling to them—and that is the basis of Buddhist teachers’ distrust. You do need to let them happen but let go of them afterward—”capture and release,” a phrase used by the Zen master Lin-Chi (Rinzai), comes to mind. I have found that hypnagogic object lessons have a brief lifespan of effectiveness anyway: They are rich and energizing and clarifying when they occur, and they can be summoned back as reminders for a day or two at most, but then they become “dead” or lose their charge, like they have only a limited battery life.

Because these kinds of insights produced by the Solaris mind are so profound and rewarding, the temptation is always to cling to them—and that is the basis of Buddhist teachers’ distrust. You do need to let them happen but let go of them afterward—”capture and release,” a phrase used by the Zen master Lin-Chi (Rinzai), comes to mind. I have found that hypnagogic object lessons have a brief lifespan of effectiveness anyway: They are rich and energizing and clarifying when they occur, and they can be summoned back as reminders for a day or two at most, but then they become “dead” or lose their charge, like they have only a limited battery life.

Hypnagogic object lessons accessed in meditation or our nightly twilight realm really are very much like the “mimoids” and “symmetriads” and other forms produced on Solaris: emerging out of the ocean, witty, playful, profound, mysterious, and then they break down or dissolve back into it. It is the rule of the oceanic Solaris mind as with anything else: Things arise and then they pass away. And eventually new ones appear, in a neverending cycle.

Living In Orbit

If hypnagogic images are like Solaris’s “mimoids” rising from the seething ocean, hypnagogia’s more solid cousins, dreams, are like the “visitors” that, in Lem’s novel, appear during the night while the scientists on the station are slumbering. The visitors in Solaris are simulacra of people associated with each scientist’s innermost desires or shames, whose company the scientist’s enjoy in an ambivalent, desultory, embarrassed fashion, knowing them to be unreal yet unable to destroy or be rid of them.

The unconscious depths plumbed somehow by the planet mind and then replicated are whitewashed and sanitized in both of the unfortunately boring film adaptations by otherwise great directors (Tarkovsky, Soderberg). In the novel, Kelvin’s dead wife is the least bizarre and embarrassing of the visitors. One of the scientists, Snow, appears to harbor a child in his quarters (and possibly also a monster) that he won’t let anyone else see, and suggests only that it represents some “uncontrollable thought” that he once had and that has now bound itself to him:

The unconscious depths plumbed somehow by the planet mind and then replicated are whitewashed and sanitized in both of the unfortunately boring film adaptations by otherwise great directors (Tarkovsky, Soderberg). In the novel, Kelvin’s dead wife is the least bizarre and embarrassing of the visitors. One of the scientists, Snow, appears to harbor a child in his quarters (and possibly also a monster) that he won’t let anyone else see, and suggests only that it represents some “uncontrollable thought” that he once had and that has now bound itself to him:

“What is a normal man? A man who has never committed a disgraceful act? Maybe, but has he never had uncontrollable thoughts? Perhaps he hasn’t. But perhaps something, a phantasm, rose up from somewhere within him, ten or thirty years ago, something which he suppressed and then forgot about, which he doesn’t fear since he knows he will never allow it to develop and so lead to any action on his part. And now, suddenly, in broad daylight, he comes across this thing…this thought, embodied, riveted to him, indestructible. He wonders where he is…Do you know where he is?”

“Where?”

“Here,” whispered Snow, “on Solaris.”

Is Snow, in his deep unconscious, a child murderer? A pedophile? Brilliantly, Lem leaves this man’s horrible materialized thought ambiguous. Snow goes on to characterize himself as “a man who at one and the same time is ashamed of the object of his desire and cherishes it above everything else, a man who is ready to sacrifice his life for his love, since the feeling he has for it is perhaps just as overwhelming as Romeo’s feeling for Juliet.”

Whatever Snow’s secret desire is, one could not ask for a better literary representation of the Real as described by Lacan: “a thought, embodied, riveted to him, indestructible.” The Real is unrepresentable and unspeakable, and it is associated with the furtive, fatal, inexplicable compulsions “beyond pleasure” that sustain us and on some deep level give meaning to our lives, even though we may have little conscious awareness of them. It is also the deepest secret buried deep in our dreams.

…Soll Ich Werden

Dreams, as I said, are elaborations of the same metabolizing imaginal-symbolic process as hypnagogia, but instead of responding to waking thoughts, they respond to inner, private realities arising in sleep: memories and desires. Psychologists now agree that REM sleep is a period of active memory consolidation, or the distillation of important daytime experiences into gists and integration of that new material into the older substrate of long-term memory.

Because each dreamer’s unique private symbolic language make studying dream content difficult in a laboratory, no scientific psychologist has yet claimed that dreams directly reflect this process. But familiarity with the classical arts of memory—which distort to-be-learned material by exactly the same processes Freud identified for dream thought—reveal that dreams must be precisely the experience of long-term memories being formed. These amazing formations (basically, multilayered polysensory puns and substitutions, organized into bizarre tableaux linked narratively and situated in a distinct spatial environment) render the “day residues” being remembered mostly unrecognizable unless subjected to free-associative unpacking.

The wit and brilliance of this process of dream distortion is so excessive, so beyond our daily experience of our mundane intelligence, that people unused to recording or observing their dreams have difficulty accepting that their own measly minds could be responsible for creating these tableaux. It may even account for why some people don’t remember them at all—they simply don’t fit into who we think we are.

To take a small, simple example, I once helped a friend make sense of a disturbing dream in which she had attended a dinner party thrown by her older sister, where she was horrified to see her sister’s head resting on a food platter, like an hors d’oeuvre. I knew that my friend felt a bit threatened by her sister’s accomplishments, such as her recent purchase of a new home, so the meaning seemed apparent: “It’s about your jealousy that your sister is ahead.” My friend’s jaw dropped, and she quickly expressed shock that her own mind, hardly a punster, would have thought of representing the idea of “ahead” with a human head … or that it would have had the bad, violent taste to create such a macabre image of her sister.

To take a small, simple example, I once helped a friend make sense of a disturbing dream in which she had attended a dinner party thrown by her older sister, where she was horrified to see her sister’s head resting on a food platter, like an hors d’oeuvre. I knew that my friend felt a bit threatened by her sister’s accomplishments, such as her recent purchase of a new home, so the meaning seemed apparent: “It’s about your jealousy that your sister is ahead.” My friend’s jaw dropped, and she quickly expressed shock that her own mind, hardly a punster, would have thought of representing the idea of “ahead” with a human head … or that it would have had the bad, violent taste to create such a macabre image of her sister.

But in fact, everyone’s dreams, as well as their hypnagogic images, are packed full of these witty puns—most of them too brilliant to ever grasp (e.g., polysensory gags). It is no wonder that dreams and other visions have historically been assumed to be messages or thoughts from some other or divine source. It’s not only, as Freud thought, that we can’t believe ourselves capable of the wicked desires our dreams sometimes hint at; it’s also that we can’t believe our own minds are capable of being so astonishingly clever.

Although materialists who reduce our dreams, as well as our other profound visionary experiences, to brain effects seem to deflate our spiritual hopes, they can also be forgiven for trying to return our genius to us—that is, to de-alienate it. Hence Freud’s motto, “Wo es war, soll ich werden” or “Where It was, there I will be.” The least of us contains infinities, and genius, that are really unimaginable, if we only bother to peer into this seething Solaris-like realm and recognize it as belonging to us—or perhaps, realize us as belonging to it.

I read this article yesterday and it has stayed with me (so I read it again just now). This is wonderful writing Eric, and you have a wonderful mind

I’m so glad to have found your blog. Thank you.