The Great Work of Immortality: Astral Travel, Dreams, and Alchemy

The ceramic-and-glass sculptures shown in this article are by artist Christina Bothwell, used with her kind permission.

Judging from the number of books and YouTube videos now available on the subject, out-of-body experiences (OOBEs) seem to be enjoying a contemporary revival, and there is surely no hobby more ontologically controversial. Several authors, including Robert Monroe (Journeys Out of the Body) claim to have had veridical experiences in a discarnate state (that is, experiences that correspond to reality) and thereby proven to their own satisfaction, if not the world’s, that one’s perceiving consciousness can exist apart from the physical body. Other writers understandably are skeptical of such claims, regarding the seeming realness of OOBEs as a cognitive or memory trick.

Whatever out-of-body experiences “really” are—actual journeys beyond the body or just lucid dreams that seem like it—it is increasingly clear that they were crucially important experiences in ancient mystical traditions.

Susan J. Blackmore, for example, initially believed in her own OOBEs’ realness but then retreated to a skeptical, safely materialist position; her 1982 book, Beyond the Body, is a thoughtful, comprehensive examination of the subject and its connection with psychical research. Recently, in his excellent exploration of Buddhist psychology and neuroscience, Waking, Dreaming, Being, Evan Thompson presents a similar narrative of youthful belief in the realness of his OOBEs followed by mature doubt. For these writers, OOBEs can only be a subset of lucid dreams—a state of being actively aware and conscious in a dream environment (in this case, one that just seems like one’s actual surroundings or other terrestrial locales). Lucid dreaming is itself an increasingly popular, albeit less controversial, contemporary hobby, thanks to the pioneering research and instruction of Stephen LaBerge. There are numerous guides to the practice available, mostly repackaging the ideas in LaBerge’s 1985 book Lucid Dreaming and in some cases incorporating Tibetan “dream yoga” techniques.

Whatever OOBEs “really” are—actual journeys beyond the body or just lucid dreams that seem like it—it is increasingly clear that they were crucially important experiences in ancient mystical traditions. Achieving these states may have been the aim of the ancient Greek shamanic practice of “incubation”—sensory deprivation in caves—as has been described in the writings of Peter Kingsley

Whatever OOBEs “really” are—actual journeys beyond the body or just lucid dreams that seem like it—it is increasingly clear that they were crucially important experiences in ancient mystical traditions. Achieving these states may have been the aim of the ancient Greek shamanic practice of “incubation”—sensory deprivation in caves—as has been described in the writings of Peter Kingsley. And thanks to the work of Jeremy Naydler

and Algis Uždavinys

, we now know that descriptions of spirit travel in Egyptian sacred ‘funerary’ texts did not simply refer to the travel of the soul in the afterlife; they reflected a proactive shamanic exercise undertaken during life. Egyptian mystics actively practiced out-of-body travel, in other words, as the ultimate philosophical preparation for death.

One could imagine other, more mundane purposes too. Given the intelligence-gathering role of prophets in ancient Israel, it would not be far-fetched to guess that the Egyptian priesthood might have employed OOBEs along with other shamanic techniques in what we would nowadays call “psychic spying” on behalf of the state. OOBEs are linked to psychic abilities like clairvoyance, and some of the foremost modern remote viewers, including Joe McMoneagle, Ingo Swann, and Pat Price, have linked their abilities directly to OOBE experiences—in Price’s case, during Scientology training. One could easily imagine Egyptian priests performing a service to the kingdom much like psychics did to the U.S. and U.S.S.R. during the Cold War.

The feminine, animal-like spirit was thought capable of leaving the body when we sleep. The Egyptians called it Ka. For pagan Europeans, it was our spirit double or feminine spirit guide.

The Middle Eastern and European traditions of alchemy that evolved out of the Egyptian mystical tradition would have carried on these practices, albeit disguised under layers of “materialistic” symbolism. Carl Jung famously illuminated the inner aspect of alchemy, arguing that the Great Work consisted of projecting unconscious mental stuff into material transformations, using laboratory processes and procedures as a symbolic control panel in personal journeys of individuation. Yet even though he described “active imagination” as a method of self-exploration, Jung to my knowledge was not aware of what we now call lucid dreaming, and even though he experienced his own OOBE, or what the spiritualists and occultists of his day called “astral projection,” after a heart attack in 1944 (what we would now call a near-death experience or NDE), I am not aware that he ever linked such experiences to what alchemists were trying to achieve.

But given what we now know of the ancient shamanic practices of Egypt that gave rise to alchemy, European alchemy’s Eastern analogues in Tantra and Yoga, and the pagan shamanic traditions that persisted on the margins of mainstream Christian culture in Europe, it becomes ever clearer that alchemical explorations would have gone, and indeed must have gone, much beyond active imagination and the projective processes Jung described. The real philosophic gold for some (or many) alchemists may have been fearlessness in the face of death—figurative “immortality”—achieved by self-induced veridical or veridical-seeming OOBEs.

Spirit and Soul

Crucially, and perhaps counterintuitively, the prerequisite for developing one’s astral capacity, in various ancient as well as modern traditions, was to cultivate not simply a Cartesian dualistic conception of psyche and soma, mind and body, but also to further subdivide the subtle psychic part of our nature into at least two distinct components of its own. Pagan and folk traditions all described a spirit with a dim animal-like awareness that was distinct from our more rarified and active, wilful, conscious component, equivalent to what in Christian tradition came to be called the soul. These were separate entities, not synonyms as they are for most people today.

In general, the feminine, animal-like spirit was thought responsible for phenomena belonging to what Freud and Jung later called the Unconscious, and was thought capable of leaving the body when we sleep. The Egyptians called it Ka. For pagan Europeans, it was our spirit double or feminine spirit guide. Claude Lecoutoux, in a fascinating study

In general, the feminine, animal-like spirit was thought responsible for phenomena belonging to what Freud and Jung later called the Unconscious, and was thought capable of leaving the body when we sleep. The Egyptians called it Ka. For pagan Europeans, it was our spirit double or feminine spirit guide. Claude Lecoutoux, in a fascinating study of European pagan/shamanic traditions about spirit doubles, shows that this component not only took nightly trips remembered as dreams but also was responsible for ghost and poltergeist phenomena as well as animal familiars. As an enlivening force, the spirit was closely allied to our breath (whence the name, spiritus); linked to our physical body, it was also connected to our bones in some intimate way. Much later, in the Theosophical tradition, it came to be known as the “etheric body”; modern New Age writers write of an “energy body” that is more or less equivalent (see below).

This feminine, energetic spiritual component was in contrast to the more rarified, conscious, aware component allied to masculine, rational, awake thought. Although this “soul” component was capable of heavenly ascent after death or during ecstatic states, in daily life it was more imprisoned in the body than the spirit component. Indeed the two parts of the subtle self tended to resist being in direct contact when not together animating the awake physical body. This soul component was the Ba of the Egyptians (capable of ascending and uniting with the transcendent Akh) and corresponds to the Theosophists’ “astral” components of the self. If you take away its ancient connotation of existing beyond death, it is more or less equivalent to what we nowadays call consciousness: the center of awake, aware subjectivity.

Such a tripartite division of our earthly existence into body, soul, and spirit seems remarkably universal across non-Judeo-Christian cultures. Whatever you call these subtle psychic components, shamans throughout the world, including in Medieval and Dark Age Europe, claimed the ability, through meditative practice and sometimes use of drugs, to yoke them together and thereby achieve the feat of leaving their bodies consciously. And, some of the most mysterious texts of 16th and 17th century alchemy show indirect or direct evidence that, whatever else they were up to, alchemical adepts were also attempting precisely these difficult “journeys beyond the body.”

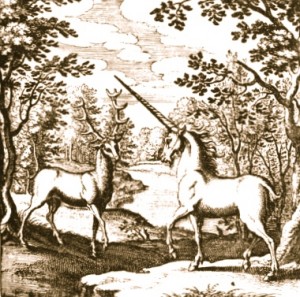

Lambspring

The clearest example is The Book of Lambspring, an alchemical poem that first circulated as a manuscript in the late 16th century and was later published with a series of beautiful illustrative engravings. It asserts that the key to riches, long life, and kinglike sovereignty over one’s existence is a process of taking the separate subtle components, soul and spirit, consciously uniting them, and leading them out of the body and back again. Among the various symbolic expressions of this are the imagery of a deer and unicorn living in a forest…

The sages say truly

That two animals are in this forest:

One glorious, beautiful, and swift,

A great and strong deer;

The other a unicorn.

They are concealed in the forest,

But happy shall that man be called

Who shall snare and capture them. …

If we apply the parable to our Art,

We shall call the forest the Body.

That will be rightly and truly said.

The unicorn will be the Spirit at all times.

The deer desires no other name

But that of the Soul; …

He that knows how to tame and master them by Art,

To couple them together,

And to lead them in and out of the forest,

May justly be called a Master.

For we rightly judge

That he has attained the golden flesh,

And may triumph everywhere;

Nay, he may bear rule over great Augustus.

Lambspring gives us further explicit indication of his belief/assertion that the soul and spirit actually leave the body during the alchemical work in the second half of his book, where he replaces the symbolism of forest, unicorn, and deer, with the more humanized symbolism of Father (body), Son (spirit), and an angelic Guide (soul). The Guide leads the Son out of the body of the Father, brings him up to the top of a “mountain in India” and carefully leads him back. This process of separating and reuniting—Separatio and Conjunctio—is one of the most central and universal motifs in European alchemy, but it is nowhere more explicitly identified as a process of leading the consciousness and spirit out of the body as it is in this book. The alchemical motto solve et coagula—”separate and reunite”—can refer on one level to this process.

On its own, Lambspring’s book would be pretty unhelpful to a modern person attempting to actually achieve an OOBE, but the author’s symbolism resonates strongly with the methods emphasized by some more modern teachers of the subject. The Theosophical tradition, which placed great emphasis on astral projection as a means of accessing cosmic consciousness (the Akashic Records, etc.) and communicating with ascended and alien intelligences, carefully emphasized the crucial role of the lower, denser “etheric body”—the subtle, energetic envelope or spiritual vehicle that could detach from the physical body on its own (dreaming) or which could, through effort, be yoked to the astral component (conscious awareness or soul) to achieve a conscious astral flight. The key to leaving the body consciously, in other words, was uniting the astral and etheric components, which, as I mentioned earlier, ordinarily don’t mix well together. (The resistance of the unconscious and conscious minds to commingle is of course a theme in Freudian and Jungian psychoanalysis, and may be seen as a kind of parallel here.)

On its own, Lambspring’s book would be pretty unhelpful to a modern person attempting to actually achieve an OOBE, but the author’s symbolism resonates strongly with the methods emphasized by some more modern teachers of the subject. The Theosophical tradition, which placed great emphasis on astral projection as a means of accessing cosmic consciousness (the Akashic Records, etc.) and communicating with ascended and alien intelligences, carefully emphasized the crucial role of the lower, denser “etheric body”—the subtle, energetic envelope or spiritual vehicle that could detach from the physical body on its own (dreaming) or which could, through effort, be yoked to the astral component (conscious awareness or soul) to achieve a conscious astral flight. The key to leaving the body consciously, in other words, was uniting the astral and etheric components, which, as I mentioned earlier, ordinarily don’t mix well together. (The resistance of the unconscious and conscious minds to commingle is of course a theme in Freudian and Jungian psychoanalysis, and may be seen as a kind of parallel here.)

One of the many modern teachers of astral projection, an Australian energy worker named Robert Bruce, has (in his book Astral Dynamics) essentially repackaged the Theosophical theory and its Eastern Tantric equivalents in modern, Western terms. Bruce teaches meditative exercises and a rather unique method of “tactile imaging” to cultivate a finer-tuned awareness of the physical body and its subtle energetic aspect (equivalent to the energy body with its nadis, chakras, etc. described in Asian systems) as a prerequisite to developing proficiency with astral travel. The separation experience at the outset of an OOBE is universally described as a vividly energetic sensation that may also resemble sensations familiar to those who have “raised their kundalini.” There is no indication in Bruce’s writing of familiarity with pagan folk traditions about the detachable spirit double, but clearly, despite using a modern computer idiom of “downloading” astral memories etc., his metaphysics are basically the same.

Energy Doubles

To my mind, the strongest evidence that Lambspring was referring to the refined, dreamlike but compellingly real-seeming state we would now call the OOBE comes from the testimony of modern astral travelers like Bruce that the key to decoupling alert awareness from the sleeping physical body is actually to be found, counterintuitively, in the reentry—the Conjunctio part rather than the Separatio. Lambspring places special emphasis on this: The Guide says to the son, “I will not let thee go alone; From thy father’s bosom I brought thee forth, I will also take thee back again.”

If you can’t recall it when you return, it’s like you never went. Developing a habit and a practice of recording dreams in the morning is a crucial preparatory step toward having a remembered astral journey.

Special care in rejoining chemical substances in physical alchemy could of course also be indicated here, but I think it signals a special concern with the process of reuniting the soul/spirit with the body as intrinsic to the success of the astral venture. The purpose of “careful reuniting” is not safety, as one might naturally suppose: Despite instinctive fears of permanent separation, there are no known cases when an astral traveler has failed to awaken safe and sound. Rather it is because the conscious portion of the self (i.e., soul or astral body) must remain in contact with the spiritual/etheric body, lest all recollection of the experience be lost. If you can’t recall it when you awaken/return, it’s like you never went. Consequently a crucial part of some modern training in OOBEs focuses on developing the capacity to remember it after the fact, because an unremembered OOBE is no OOBE at all.

This is the most crucial piece of advice given by Bruce: He even suggests that we are astrally projecting all the time but lack memory of it; thus his method focuses on initially keeping flights brief and then celebrating and recording one’s small successes. Developing a habit and a practice of recording dreams in the morning is a crucial preparatory step toward having a remembered astral journey.

This is the most crucial piece of advice given by Bruce: He even suggests that we are astrally projecting all the time but lack memory of it; thus his method focuses on initially keeping flights brief and then celebrating and recording one’s small successes. Developing a habit and a practice of recording dreams in the morning is a crucial preparatory step toward having a remembered astral journey.

The relationship between OOBEs and lucid dreams is widely disputed, but the same “induction” methods work for both, not to mention the necessity of keeping records afterward. This is true of any dream-work, as I’ve argued previously in the context of precognitive dreaming. Anyone who knows the extraordinary value of attention to dreams (even in a simply psychoanalytic vein) knows you will have a hard time remembering a dream or its crucial innocuous-seeming details if you don’t write it down right away, or at least jot down a few words to jog the memory when you have time to record it more fully later in the day.

Atalanta Fugiens

My favorite 17th-century alchemical text, Atalanta Fugiens by Michael Maier, contains among many other things a coded recommendation about keeping a dream diary, likely as preparation for more advanced Tantric or OOBE exercises.

It’s a very special quality of dreams that they evaporate very quickly and must be seized immediately after they occur or they are lost forever. Quick note-taking is required to fix this volatile substance.

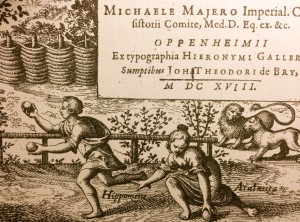

The title of this lovely collection of engravings and accompanying poems and fugues, literally “Atalanta Fleeing,” refers to Ovid’s story about the race between the beautiful fleet-footed virgin Atalanta and her would-be suitor Hippomenes. The central secrets of alchemical books are sometimes hidden in plain sight right in their title pages, like Poe’s “purloined letter,” and this is true of Atalanta Fugiens, whose frontispiece depicts various scenes from the Atalanta legend. The 50 emblems and commentaries in the book supposedly relate in various ways to the Hermetic themes of that ancient myth.

Atalanta was the fastest in the land—so fast she couldn’t be caught—and would only marry a suitor who could beat her in a race. Hippomenes wins the race (and her hand in marriage) by availing himself of three gold apples given to him by Venus; during the race, he throws the apples on the ground, one by one, each time catching Atalanta’s attention and slowing her down (you know, the way even tomboy girls are easily distracted by pretty, shiny things). After winning the race, Hippomenes steals a kiss from his new bride in Aphrodite’s temple and the couple (as punishment from that goddess) are turned into lions. The conflict of two lions (and/or dragons) resulting in their ultimate union—again, soul and spirit which do not initially get along but which, with difficulty, can be forced into a productive merger—is a near-universal alchemical motif.

Atalanta was the fastest in the land—so fast she couldn’t be caught—and would only marry a suitor who could beat her in a race. Hippomenes wins the race (and her hand in marriage) by availing himself of three gold apples given to him by Venus; during the race, he throws the apples on the ground, one by one, each time catching Atalanta’s attention and slowing her down (you know, the way even tomboy girls are easily distracted by pretty, shiny things). After winning the race, Hippomenes steals a kiss from his new bride in Aphrodite’s temple and the couple (as punishment from that goddess) are turned into lions. The conflict of two lions (and/or dragons) resulting in their ultimate union—again, soul and spirit which do not initially get along but which, with difficulty, can be forced into a productive merger—is a near-universal alchemical motif.

We are meant to ask, what is it that flees and how can you stop it from fleeing? The name Atalanta, meaning “equal in weight or value,” does not really give a clue to the nature of the volatile substance. But Hippomenes himself can tell us a lot. The name can be parsed firstly as hippo-menes or “horse mind,” which by itself signals that we may apply the wild-etymological method that the great 20th-century adept Fulcanelli called cabala (from caballus, horse), and redivide the word however we see fit. The most obvious re-parsing is hip-pommes, or “dropped apples,” which doesn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know. But there is a very similar Greek word, hypomnema, which meant a reminder, a note jotted down. It happens that Emblem VI depicts this process explicitly: A farmer tosses gold coins onto furrowed ground (a gesture similar to Hippomenes tossing golden apples), accompanied by the motto: “Sow your gold in the white foliate earth.” Hippomenes thus seems to be a pun for the very thing indicated by “white foliate earth” with its “sown gold”—that is, hypomnema, precious reminders of something fleeting, jotted down (sown) in the white pages (folia or leaves) of a notebook.

Keeping records of laboratory procedures and results and the visible changes occurring in the retort would be an obvious interpretation here, not to mention the ultimate creation of a book that will serve to guide others: the alchemical text itself as philosopher’s stone. But are consciously observed chemical reactions, however fleeting, so ephemeral (or volatile) that they are completely forgotten unless fixed in the very moment they occur? No—it’s a very special quality of dreams and related phenomena like hypnagogic/hypnopompic images that they evaporate very quickly and must be seized immediately after they occur or they are really lost forever. Quick note-taking is required to fix this volatile substance.

Keeping records of laboratory procedures and results and the visible changes occurring in the retort would be an obvious interpretation here, not to mention the ultimate creation of a book that will serve to guide others: the alchemical text itself as philosopher’s stone. But are consciously observed chemical reactions, however fleeting, so ephemeral (or volatile) that they are completely forgotten unless fixed in the very moment they occur? No—it’s a very special quality of dreams and related phenomena like hypnagogic/hypnopompic images that they evaporate very quickly and must be seized immediately after they occur or they are really lost forever. Quick note-taking is required to fix this volatile substance.

There is way, way more that could be said about Atalanta Fugiens, which contains enough fascinating “Tantric” imagery to reward years of perusal and study. But let me move on to a third book that most explicitly addresses the link between dream life and OOBEs and also uses its own brilliant symbolism for dream recording.

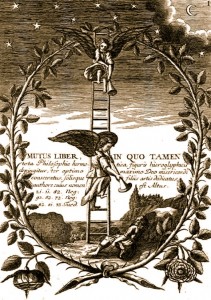

Mutus Liber (Enlightenment by Means of Dew)

The 1677 alchemical masterpiece Mutus Liber (or “Silent Book”) is a series of mostly wordless alchemical ‘cartoons’ by a writer with the pseudonym “Altus,” depicting a complicated esoteric process undertaken by a pair of adepts, one male, one female. (Sometimes it is described as a male alchemist and “his” female assistant, wife, Tantric soror mystica, or Jungian Anima, but the book gives no cause to privilege the male figure over the female—they both seem to play equally important roles.) This book is another example of an alchemical text that hides its cipher in plain sight, right on its title page.

The frontispiece depicts Jacob’s famous dream in Genesis 28, of angels ascending and descending a ladder to heaven. Any reader would know that, in that story, right after he awakens, Jacob anoints the stone he has used for a pillow beth-el, “House of the Lord”; until the arrival of Christ himself in the Old Testament’s sequel, this stony pillow is perhaps the clearest and most literal expression of the Philosopher’s Stone in the Bible. But more crucially for the book we are concerned with here, the Jacob frontispiece includes three backwards chapter/verse numbers in Hebrew, each referring to Biblical passages about heavenly “dew.” The centrality of dew in this book is also signaled cleverly by the roses framing the scene: Rose is a pun on the Latin word for dew, ros (which should also give you a clue to the ‘true’ meaning of the rose in other esoteric contexts, such as Rosicrucianism).

The frontispiece depicts Jacob’s famous dream in Genesis 28, of angels ascending and descending a ladder to heaven. Any reader would know that, in that story, right after he awakens, Jacob anoints the stone he has used for a pillow beth-el, “House of the Lord”; until the arrival of Christ himself in the Old Testament’s sequel, this stony pillow is perhaps the clearest and most literal expression of the Philosopher’s Stone in the Bible. But more crucially for the book we are concerned with here, the Jacob frontispiece includes three backwards chapter/verse numbers in Hebrew, each referring to Biblical passages about heavenly “dew.” The centrality of dew in this book is also signaled cleverly by the roses framing the scene: Rose is a pun on the Latin word for dew, ros (which should also give you a clue to the ‘true’ meaning of the rose in other esoteric contexts, such as Rosicrucianism).

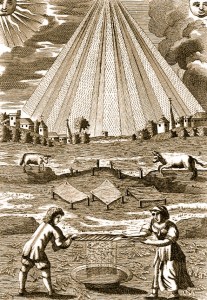

The stuff of dreams is the materia prima, the murky raw material that must be taken, analyzed, worked with, to create true philosophic gold.

In subsequent panels, the alchemists are depicted engaging in various laboratory operations utilizing dew that has been initially collected in an array of sheets during spring mornings, the season being symbolized by a ram and bull, Aries and Taurus, rampant in the background (although the animals could have other connotations—see below). As a means of collecting literal nocturnal moisture, wringing out sheets one has suspended on posts in a field seems that it might be highly impractical. But “dew” is not meant to be taken literally here.

Adam McLean’s diagram of the process, provided in his Magnum Opus Hermetic Sourceworks Commentary

Adam McLean’s diagram of the process, provided in his Magnum Opus Hermetic Sourceworks Commentary, is invaluable for keeping track of the operations and the dense symbolism in Mutus Liber. For another modern interpreter writing under the name Eli Luminosus Aequalis

, these sheets represent the five senses, and his subsequent analysis depicts a noetic, epistemic, and Tantric process. I agree with many of Eli’s interpretations, but I think he is wrong about the ingenious symbolism of dew itself and its collection on bedsheets: What else is it that appears in the early morning hours and evaporates quickly with the dawn, and that one might carefully and quickly collect ideally while still lying in bed? The same thing Maier represents by the fleeing Atalanta, and the same thing Jacob is shown in the process of doing right on this book’s title page.

Mutus Liber is actually pretty explicit about what we are supposed to do with this figuratively dew-like substance collected over a series of spring mornings. Subsequent panels depict an elaborate process of distilling and then mixing the dew’s various components in different combinations. Assuming I am right about the identity of “dew,” the process begins with what I believe to be isolating repeated dream motifs from other symbolic stuff and Freudian day residues and then using these recurring motifs as mnemonic triggers to wake up inside the dream (lucidity). This is the mnemonic-induced lucid dreaming (MILD) method recommended by LaBerge, and it may be taken as the equivalent of yoking soul and spirit and exiting the sleeping body consciously, as in Lambspring. Eli Luminosus Aequalus likewise argues that this part is about lucid dreaming. I imagine though that, at the time Altus was writing, there would have been no distinction between such ‘mere’ dream experiences and what we would now call OOBEs or astral travel.

Developing lucid dreaming capacity is useful for achieving a full-on OOBE and lucid dreams are the more common experience when the latter fails. Also, it is only in preparing for and interpreting an OOBE as such that one needs to first understand (or, be persuaded) that the spiritual component is distinct from consciousness imprisoned in the body (i.e., the first phase of the Mutus Liber process), which then enables one to learn to unite the consciousness with the spirit while leaving the body behind (the second phase), and lastly bring them together, followed by repetition of the process over time such that it becomes easier (lather, rinse, repeat).

The key to riches, long life, and kinglike sovereignty over one’s existence is taking the soul and spirit, consciously uniting them, and leading them out of the body and back again.

So I think that the Mutus Liber is basically a Baroque astral projection manual disguised as chemistry: The stuff of dreams is the materia prima, the murky raw material that must be taken, analyzed, worked with, to create true philosophic gold: a special “blended” state in which the soul (alert consciousness) fully joins with the spirit double/”energy body” on its nightly travels. Successive separations and conjunctions (returns) exalt the self and lead to enlightenment. Over the course of the book, the curtains behind the alchemists progressively open, letting more and more light into their workshop.

Why All the Secrecy?

Beliefs in the separability of consciousness from the body prior to death were antithetical to Christian theology: Humans possessed just a single “subtle” principle, the soul, which departed the body only in death. Jesus was the singular exception, the only person possessing a divine spirit as well as a soul. As a result, all ordinary human phenomena hinting at spirit—from dreams and visions and mystical and other altered states of consciousness to manifestations of what we would now call “the paranormal,” like ghosts or psychic phenomena—were at least distrusted and were often relegated wholly to the category of the demonic. You could say, Christianity successfully robbed religion of spirit, replacing it with faith.

Whether or not we nowadays accept that each person possesses both detachable components, the work of Lecoutoux (for Europe), Naydler (for Egypt), and other scholars makes clear that it was firmly a part of pre- and para-Christian folk psychology, supported by infrequent but remarkable experiences like spontaneous OOBEs, lucid dreams, sleep paralysis episodes, near-death experiences, drug experiences, etc. The continuity of shamanic practices under various alternative labels (black magic, sorcery, witchcraft, etc.) in Christian Europe was certainly genuine, even if their prevalence and power was exaggerated by Church authorities. Alchemical explorers of consciousness would have pursued these techniques, marvelously and densely disguising their efforts under their chemical symbology.

Whether or not we nowadays accept that each person possesses both detachable components, the work of Lecoutoux (for Europe), Naydler (for Egypt), and other scholars makes clear that it was firmly a part of pre- and para-Christian folk psychology, supported by infrequent but remarkable experiences like spontaneous OOBEs, lucid dreams, sleep paralysis episodes, near-death experiences, drug experiences, etc. The continuity of shamanic practices under various alternative labels (black magic, sorcery, witchcraft, etc.) in Christian Europe was certainly genuine, even if their prevalence and power was exaggerated by Church authorities. Alchemical explorers of consciousness would have pursued these techniques, marvelously and densely disguising their efforts under their chemical symbology.

Thus in their writings alchemists perpetually did a subtle dance around this issue of our subtle self: Is it one thing or two? When they wrote explicitly about soul and spirit as distinct, it was important to emphasize either that they were referring to physical chemistry—in which “spirits” are light volatile distillates (like alcohol) and the “soul” of a substance could stand for its oily and more distinct extracts—or alternatively, to insist that “the two are really one.” We see this evasiveness clearly in Lambspring’s opening verse. The author says “the sages will tell you” that the body contains a soul and a spirit and that “nevertheless they are one.” Lambspring himself, weighing in on this, is more equivocal: “Now I tell you most truly, cook these three together … and hold your tongue about it.” He seems to be saying that body, soul, and spirit really are in some sense three things, but if you are smart, you won’t admit to holding such a belief.

The extent to which this Christian duality of the person influenced subsequent rationalist, materialist tradition have been less acknowledged. Enlightenment science and the rationalist tradition carried forward the Christian presumption of a singular mental principle that might somehow be distinct from the body, as in Descartes, and required no third intermediary, no third term mediating them or yoking them together, other than God himself. The result has been an almost complete erasure of the ancient and pagan traditions about spirit doubles, as well as lingering confusion about what spirit and soul mean. Most people now use the terms interchangeably, unaware that there was once a meaningful distinction.

Anyone who in their own spiritual explorations has realized the importance of figuring out just what (the hell) out-of-body experiences really are knows how difficult it can be, and also how worthwhile the pursuit as revealed by even the first glimmers of success.

To this day, we have difficulty conceptualizing a consciousness that is not somehow unified, yet we also perpetually have trouble conceptualizing how these two radically different things, consciousness and the physical body, could be linked together. They seem to need a mediator that our metaphysics completely lacks. Descartes’ famous search for the seat of consciousness in the pineal gland is emblematic of the felt need for some mysterious mediating principle to yoke the soul to the living body.

It was of course the genius of Freud and his followers like Jung to renew our sense of the psyche’s plurality, resolving it into the conscious and unconscious components as well as parsing psychological functions in various other ways. But even Jung and the analytical psychology he inspired continue to implicitly see the psyche as one thing, even if the person has delusionally lost sight of this unity through a refusal to recognize rejected components of self; spirit and soul are merely aspects of the same underlying consciousness that would realize its unity through individuation. For instance, the Jung-inspired writer James Hillman described the soul as the humid enclosed “valleys” where we live surrounded by the familiar local particulars of our lives, and the “spirit” as the mountain peaks to which we may at times loftily ascend, attaining a clearer, more objective, more far-seeing view. They are places our singular consciousness moves between, not actual separable components of our being. Lambspring’s “mountain in India” where the soul and spirit ascend in tandem, would make no sense in Hillman’s framework.

Laughing at Death

Anyone who in their own spiritual explorations has realized the importance of figuring out just what (the hell) OOBEs really are knows how difficult it can be—with months or years of setbacks, disappointment, and discouragement—and also how worthwhile the pursuit as revealed by even the first glimmers of success. Ordinary lucid dreaming, the continuity of consciousness in a typical dream environment and at least a related phenomenon (if not the same), is supremely exhilarating and empowering—famously a route to gaining control over one’s fears and nightmares, much the way virtual reality is used to desensitize people from phobias or train extraordinary and dangerous skills. Actual OOBEs in “Reality I” (Monroe) or the “real time zone” (Bruce)—that is, experiences in which the immediate physical environment and even one’s own sleeping body seem to be perceived and interacted with—certainly would provide the experiencer with an even greater validation of the separability of one’s consciousness from material existence and, as an inevitable corollary, its possible survival of bodily death.

Such experiential verification of the indestructibility of consciousness would be priceless to humans living in the constant terror of mortality, so it is no wonder that, in the centuries before we could automatically blame such experiences on the material brain, such experiences constituted an “elixir of immortality” (i.e. as proof of immortality), as well as a talisman of power and health and courage. Once the son and father are reunited in Lambspring’s final verse, “they produce untold precious fruit. They perish never more, and laugh at death.” Assurance of the independence of consciousness from the body would indeed tend to make one brave in life, and this courage would tend to produce power and success. Once you’ve glimpsed it or been convinced there could be something to it, it really is something worth devoting energy and time to exploring.

Such experiential verification of the indestructibility of consciousness would be priceless to humans living in the constant terror of mortality, so it is no wonder that, in the centuries before we could automatically blame such experiences on the material brain, such experiences constituted an “elixir of immortality” (i.e. as proof of immortality), as well as a talisman of power and health and courage. Once the son and father are reunited in Lambspring’s final verse, “they produce untold precious fruit. They perish never more, and laugh at death.” Assurance of the independence of consciousness from the body would indeed tend to make one brave in life, and this courage would tend to produce power and success. Once you’ve glimpsed it or been convinced there could be something to it, it really is something worth devoting energy and time to exploring.

Assurance of the independence of consciousness from the body would indeed tend to make one brave in life, and this courage would tend to produce power and success.

The methods are, and were, various. In the excellent recent collection of essays, Alchemical Traditions (edited by Aaron Cheak), Hereward Tilton examines the writings of the 16th Century alchemist Heinrich Khunrath and his contemporaries, and concludes that Khunrath’s work described (and concealed) processes that resulted in the creation of diethyl ether—a potent anaesthetic. Ether may have been literally the philosopher’s stone for Khunrath, which supports the idea that European alchemists were indeed engaged in a project of exploring and using altered states of consciousness. Anesthetics particularly are notable for producing profound dissociative or out-of-body experiences.

But what the user gains in facility of entering an altered state using drugs may be canceled by the difficulty of controlling the experience and, in the modern world at least, easy dismissal of the experience’s validity. Thus while entheogens may provide an important taste of out-of-body or lucid-dream-type experiences, the holy grail really seems to be the production of these experiences solely through meditation and other non-chemical techniques. The original alchemical text, the Tabula Smaragdina or Emerald Tablet, tells us that “the wind carried it in its belly,” which points directly to meditation as the method of the Great Work. The link between breath (the original meaning of “spirit”) and thought is well-known in many traditions, and so it was surely central to ancient contemplative practices and trance.

There are plenty of guides out there now to enable one to learn to have OOBEs and ascertain for yourself whether they are merely a subset of lucid dreams—obviously the only scientifically and socially acceptable materialist interpretation—or something more. I’ve mentioned a couple of them, but the very best books on the subject are from early in the last century. My favorite, and the most interesting, is the 1929 book The Projection of the Astral Body, a collaboration between an articulate lifetime ‘projector’ Sylvan Muldoon and psychical researcher Hereward Carrington. It includes thorough discussion of the means of inducing these experiences as well as interesting suggestions of their link to other phenomena like sleep paralysis (“astral catalepsy”) and hypnic jerks (“repercussion”). Those authors mention a 1920 series of articles by projector Oliver Fox, subsequently published as Astral Projection, which I also really like—it is less comprehensive, but more personal, and also more frank about the difficulties and disappointments inherent in the practice, such as the increased difficulty of having such experiences with age.

There are plenty of guides out there now to enable one to learn to have OOBEs and ascertain for yourself whether they are merely a subset of lucid dreams—obviously the only scientifically and socially acceptable materialist interpretation—or something more. I’ve mentioned a couple of them, but the very best books on the subject are from early in the last century. My favorite, and the most interesting, is the 1929 book The Projection of the Astral Body, a collaboration between an articulate lifetime ‘projector’ Sylvan Muldoon and psychical researcher Hereward Carrington. It includes thorough discussion of the means of inducing these experiences as well as interesting suggestions of their link to other phenomena like sleep paralysis (“astral catalepsy”) and hypnic jerks (“repercussion”). Those authors mention a 1920 series of articles by projector Oliver Fox, subsequently published as Astral Projection, which I also really like—it is less comprehensive, but more personal, and also more frank about the difficulties and disappointments inherent in the practice, such as the increased difficulty of having such experiences with age.

Depending on how old you are, having OOBEs may prove much more difficult than most enthusiasts like to claim. Despite a few spontaneous OOBEs when I was a young adult and another about 18 years ago, deliberately bringing one on in my late forties has proven extraordinarily difficult—only one full-on success thus far, as well as many attempts resulting in lucid dreams or other precursor phenomena like sleep paralysis and strong energy- or Kundalini-like sensations like those described in the manuals.

It is plenty to satisfy me that the ancient and modern authors are not simply lying about the experience. Whatever is really happening in OOBEs, they do feel distinctly real/veridical in a way that lucid dreams do not, even though the surest method of induction—basically, sensation-focused meditation while lying in bed—is the same, as are the unusual, initially alarming energetic sensations frequently preceding or accompanying them. Meditative work with hypnagogia during the day or evening can also bring on remarkably real-seeming “remote viewing”-like experiences without the ability to actually move around in the seen environment; but “real seeming” isn’t necessarily the same as real. I’m still on the fence about the nature of all these phenomena and how they relate to each other. That they are indeed related seems undeniable, however.

Postcript: What Are Sheep?

Rams and sheep appear throughout alchemy, and they also have a little-noticed symbolic connection to sleep going back hundreds or, I suspect, thousands of years.

Sheep, which must be closely watched at night, are like dreams, and shepherds are watchers of dreams.

First, the alchemical Great Work is always said to originate under the sign of Aries, the ram—ordinarily taken to mean the season of spring, which is what seems to be shown in Mutus Liber. Aries is symbolically associated with Mars (Ares) and the metal iron, which Fulcanelli emphasizes throughout his fascinating writings (for a tantalizing invitation down the rabbit hole of alchemy, the best place to start is Fulcanelli’s Mystery of the Cathedrals). Like many alchemical writers, Fulcanelli also draws our attention to Jason and the Argonauts’ quest for the Golden Fleece, which has long served as an allegorical representation of the Great Work. Fulcanelli helpfully points out that the mysterious object of that quest, the fleece of the self-sacrificing golden ram Chrysomallus—was guarded by a dragon, etymologically from derkesthai, “ever vigilant” or “awake while sleeping.”

Sheep, which must be closely watched at night, are like dreams, and shepherds are watchers of dreams—like dragons, they are “awake while sleeping.” The motif of the shepherd as dreamer, having fallen asleep on the job, appears throughout European art and literature, and it has ancient roots with the mythical Endymion, the handsome shepherd placed in a perpetual sleep to be adored in slumber by the moon goddess Selene.

Sheep, which must be closely watched at night, are like dreams, and shepherds are watchers of dreams—like dragons, they are “awake while sleeping.” The motif of the shepherd as dreamer, having fallen asleep on the job, appears throughout European art and literature, and it has ancient roots with the mythical Endymion, the handsome shepherd placed in a perpetual sleep to be adored in slumber by the moon goddess Selene.

Then of course there is “counting sheep” as a supposed cure for insomnia. It was recorded first in the 12th century but could be far older: There is a possible folk etymology linking the Latin imperative sopor sond (“sleep soundly”) to the Hebrew sopwor tsoan (“count sheep”), and whether or not this is really the origin of the idea of counting sheep in connection to sleep, the linkage of sheep/shepherds and dreams is clearly ancient. I think it is possible that, as a focus of conscious awareness, counting sheep might originally have been intended, not to induce sleep, but as a meditative bridge to lucid dreaming using the wake-induced lucid dream—WILD—method described by LaBerge. In my experience, maintaining fixed meditative awareness across the sleep threshold is, although challenging, far more reliable than attempting to wake up in a dream once it has begun using a lucidity trigger, per the MILD method.

If sheep are an ancient symbol for dreams, then the ram, a male sheep, may also be specifically symbolic of dream lucidity. Ra, the nocturnal incarnation of Osiris, is depicted with a ram’s head in his nightly voyage through the Duat or Underworld. The name of the Egyptian soul, Ba, also the word for ram, may have been an onomatopoeia, from the sound sheep make (i.e., “baa”).

In light of this, the many other sheep and shepherding references in the Genesis story of Jacob signaled by Altus at the start of his “Mute Book,” become suggestive. After his dream, Jacob goes on to visit the land of his cousin Laban, where shepherds gathered at a watering hole cannot refresh their flocks alone but must wait for all of them to gather so they can roll away a large stone that blocks the spring. When Laban’s daughter Rachel, a shepherdess, arrives, Jacob is smitten and singlehandedly rolls away the rock so he can water her sheep. The power to bring on dream experience during daylight perhaps depends on an erotic power either sublimated or channeled in actual Tantric work with a partner—suggested perhaps by the partnership of male and female alchemists in Altus’s book. There are other suggestions in Jacob’s narrative that he was actually some kind of shaman and/or trickster, including his fooling of his blind father by donning the skin of a goat.

If I am right about the ancient esoteric symbolism of sheep, then we ought also to read Luke’s gospel in the New Testament as an alchemical text, because it encodes the same esoteric awareness. Christ was born at night, and in Luke alone among the Gospels the first people to be made aware of his birth were the shepherds in the fields. The esoteric significance of the adoration of the shepherds would have been apparent to Luke’s intended audience: Christ appeared first to the shamans and dreamers. (In Matthew of course, his first visitors were instead the Magi from the East—possibly signaling a Vedic, Buddhist, or Tantric commitment on the part of that author.)

Christ was the Lamb of God, sacrificed in the cruciform manner of the Paschal Lamb, bringing full circle the sacrificial substitution of a ram for Abraham’s only son in Genesis. In earliest Christian iconography, Christ was depicted not crucified but bearing a sheep over his shoulders (the “Good Shepherd,” per one apocryphal text). The pseudonym “Lambspring” of course would have been a Christian allusion, and also, I suggest, another veiled reference to the subject of his book: the ability of the soul and spirit to “spring” (project) out of the body.

Christ was the Lamb of God, sacrificed in the cruciform manner of the Paschal Lamb, bringing full circle the sacrificial substitution of a ram for Abraham’s only son in Genesis. In earliest Christian iconography, Christ was depicted not crucified but bearing a sheep over his shoulders (the “Good Shepherd,” per one apocryphal text). The pseudonym “Lambspring” of course would have been a Christian allusion, and also, I suggest, another veiled reference to the subject of his book: the ability of the soul and spirit to “spring” (project) out of the body.

The secret subject of these ancient esoteric traditions, of course, is consciousness. Christ is awake, aware consciousness, the union of Soul and Spirit, martyred on the ancient symbol of matter, the Cross, which means both the body and light (because the Latin letters in “LVX” can be formed from +), but capable of transcending the dream of ordinary existence through realization of immortal life. His resurrection is enlightenment, which we all have in our power to achieve through meditation, particularly meditation on, with, and in our nightly dreams.

It’s definitely not easy! I achieved my initial successes with the aid of a relatively safe nootropic supplement called Galantamine, which you can buy cheaply online. There are lots of instructions online about how to use it to help with lucid dreaming: basically, wake up after a few hours of sleep, in the early morning, and take the capsule, then go back to sleep–it acts at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and creates a kind of alertness that can facilitate waking up in the dream. But tolerance develops very quickly so you should only use it once a week, and best just a few times to sort of open the door to the experience and gain initial practice, then learn to bring them on without chemical help (i.e. meditation).

It’s definitely not easy! I achieved my initial successes with the aid of a relatively safe nootropic supplement called Galantamine, which you can buy cheaply online. There are lots of instructions online about how to use it to help with lucid dreaming: basically, wake up after a few hours of sleep, in the early morning, and take the capsule, then go back to sleep–it acts at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and creates a kind of alertness that can facilitate waking up in the dream. But tolerance develops very quickly so you should only use it once a week, and best just a few times to sort of open the door to the experience and gain initial practice, then learn to bring them on without chemical help (i.e. meditation).

Hi Eric, another great blog entry!

This is a subject I’m extremely familiar with, yet once again you’ve formulated & expressed ideas in a somewhat unique way I hadn’t explicitly considered before – very helpful, thanks!

A while ago somebody asked me for my (detailed) thoughts on lucid dreaming/astral projection and any tips I may have, so I wrote up a long, rambling most incoherent email to him, which I also posted on the forum I met him on. What you are suggesting in your post is something I believe I kind of touched on, without being as explicit as yourself:

“The secret to successful, consistent & “at will” OBEs is to forge a strong and ongoing connection between the waking mind and the dreaming mind. Really, this was the biggest secret for me personally that really helped me to become good at it……

As most people are hardly ever even vaguely aware of their dreaming mind, let alone intimately familiar with it, the first step is to get to know it…..and the easiest possible way is to pay very close attention to your dreams. A “dream diary” may well be the most important tool in any OBErs, astral projectors or lucid dreamers tool kit that they will ever have. If you feel you can skip this step, like many do, then you may as well skip the entire endevour. This is the foundation of any strong OBE ability. Also know, deep down, it is important. In this way you’re paying respect, with your waking mind, to your dreaming mind.”

(not sure if external links are allowed, but entire post here: http://www.skeptiko-forum.com/threads/lucid-dreaming-tips.1263/)

Your section on the Book of Lambspring (thanks for the reference – had already read the other 2 alchemical texts mentioned, but never heard of this one, will be checking it out in full!) reminded me of what I was attempting to hint at in my email…..it’s opened up new ways of thinking for me….which is nice

PS – you mention entheogens and astral projection/lucid dreaming – being quite familiar with both (including DMT, mushrooms, LSD, Salvia), I would personally have to strongly suggest they are indeed entirely different things, really. Though that is not a popular view, these days, with DMT/Ayahuasca and other entheogens being en vogue – I agree with your comment regarding it!

PPS – Have you read any Patrick Harpur? His book Mercurius hints at a similar reading of the great alchemical work as your readings above – he suggest the “philosophers stone” is the “imagination” (or imaginal realm)….

Fascinating!

Cheers, Manu