Time Loop at Hanging Rock

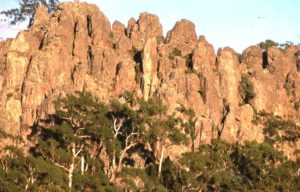

Valentine’s Day, 1900. A group of Australian schoolgirls, all clad in white dresses, are driven by coach to Hanging Rock, an enormous volcanic formation in central Victoria, Australia, for an afternoon picnic. Four girls, including the most popular, Botticelli Venus-looking Miranda (played by Anne-Louise Lambert), defying the orders of the school’s stern headmistress, venture off from the group, ascending through a maze of crevices in a kind of dreamy reverie; later, one girl, Edith—the least pleasant of the lot—reappears, disheveled and upset. The rest have seemingly vanished into thin air—along with the school math teacher, Mrs. McCraw, who had followed after them.

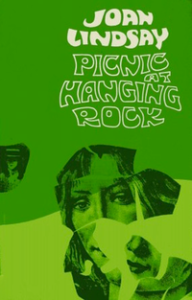

Thus begins Peter Weir’s debut masterpiece Picnic at Hanging Rock, one of the many gems of mid-1970s cinema (and recently remade as a 6-part Amazon miniseries, which I have not seen). I have always had good memories of Weir’s 1975 film from seeing it on television when I was young, and even vaguely thought of it as a “paranormal” movie, although without remembering quite why. When I watched it recently for the first time in probably two decades, I was again stunned at its beauty, and like many viewers I was gripped by the mystery that is presented as somehow, vaguely, a “true story.” A visit to Google immediately after the credits rolled revealed a much more complex and ambiguous reality. It turned into a month of gathering and reading everything I could about the source novel and its author, Joan Lindsay.

There are so many fascinating wrinkles to the story that it is hard to know where to begin. First, if you have never seen the film, do yourself a favor and watch it. With its gorgeous cast and costumes and scenery and a Georghe Zamfir pan-flute melody that will be stuck in your head for days, it is brilliant from start to finish. But no spoiler warnings are really necessary, because none of the questions raised in the first 30 minutes of the film are answered by the end. The mysteries only deepen as the remaining schoolgirls and their teachers and headmistress—as well as two young men who were the last to see the girls ascending the rock—attempt to unravel the mystery and deal with the consequences of the girls’ disappearance.

There are so many fascinating wrinkles to the story that it is hard to know where to begin. First, if you have never seen the film, do yourself a favor and watch it. With its gorgeous cast and costumes and scenery and a Georghe Zamfir pan-flute melody that will be stuck in your head for days, it is brilliant from start to finish. But no spoiler warnings are really necessary, because none of the questions raised in the first 30 minutes of the film are answered by the end. The mysteries only deepen as the remaining schoolgirls and their teachers and headmistress—as well as two young men who were the last to see the girls ascending the rock—attempt to unravel the mystery and deal with the consequences of the girls’ disappearance.

We never find out what happened to the girls, and there are only subtle hints of anything paranormal in the film, or even in the book, unless you are paying close attention. The paranormal is mainly in the backstory of the author, the unusual circumstances of the writing of her 1967 novel, and especially in what was excised from the text prior to publication. Lindsay’s novel turns out to be a kind of “fractal” representation of the paranormal and its fate in our culture: to be “disappeared,” just like the alluring, disobedient schoolgirls.

Time Without Clocks

The 70-year-old Joan Lindsay wrote her novel, which quickly became a classic of Australian fiction, over the course of a mere week in 1966, after a series of obsessive dreams. The whole novel came to her in these dreams, and it did have at least one obvious autobiographical component. Appleyard College in the novel was clearly based on a real private girls’ boarding school, the Clyde School in Mt. Macedon, near Hanging Rock, which she had attended as a young woman in the late 19-teens. She prefaced her novel with the words “Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction, my readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen hundred, and all the characters who appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important.”

Well, you could not ask for a more powerful invitation to discover the “truth” behind the mystery. And there is nothing like the mysterious disappearance/death of beautiful young women to fire the imagination. Just ask David Lynch. The novel, with the help of Weir’s film, which the author fully endorsed, cast a spell on a nation. Especially after the film was released in 1975, Australian fans obsessively scoured newspapers from the period for reports of missing schoolgirls at Hanging Rock—in vain. One critic, Yvonne Rousseau, compiled various theories of the girls’ disappearance in her 1988 book The Murders at Hanging Rock.

Well, you could not ask for a more powerful invitation to discover the “truth” behind the mystery. And there is nothing like the mysterious disappearance/death of beautiful young women to fire the imagination. Just ask David Lynch. The novel, with the help of Weir’s film, which the author fully endorsed, cast a spell on a nation. Especially after the film was released in 1975, Australian fans obsessively scoured newspapers from the period for reports of missing schoolgirls at Hanging Rock—in vain. One critic, Yvonne Rousseau, compiled various theories of the girls’ disappearance in her 1988 book The Murders at Hanging Rock.

In reality, Hanging Rock had been a pretty dangerous place in the late 1800s. People sometimes did go missing. Prospectors returning to Melbourne from nearby gold fields were sometimes robbed and murdered there. According to a 1975 documentary about the film, a nearby town has a monument to three children who went missing sometime in the late 1800s. The Rock also was “haunted” by Australia’s colonial history and the murder of indigenous peoples, for whom the site was regarded as sacred. Visitors still regard it as a spooky, mysterious place.

Another clear influence on Lindsay’s novel was a painting that had hung in the office of her husband, Sir Daryl Lindsay, a famous Australian painter and director of the Australian National Gallery. At the Hanging Rock (below) by William Ford shows a group of Victorian picnickers under the looming formation, in what could almost be a promotional still for Weir’s film.

But a few astute readers and friends of Joan Lindsay had all along suggested that there was something else going on with the novel, and that it had to do with the author’s unusual beliefs about time. At the beginning of the story (and the film) the visitors’ watches all are found to have stopped in the vicinity of the rock. And there is an odd, easily overlooked but telling detail early in the novel when the girls who have left the group gaze down on the valley below and muse philosophically on human purpose, almost like aliens surveying people from some Archimedean vantage point; one of the girls then hears a sound like drums:

The plain below was just visible; infinitely vague and distant. Peering down between the boulders Irma could see the glint of water and tiny figures coming and going through drifts of rosy smoke, or mist. ‘Whatever can those people be doing down there like a lot of ants?’ Marion looked out over her shoulder. ‘A surprising number of human beings are without purpose. Although it’s probable, of course, that they are performing some necessary function unknown to themselves.’ … The ants and their business dismissed without further comment. Although Irma was aware, for a little while, of a rather curious sound coming up from the plain. Like the beating of far-off drums.

Readers who are paying attention note that a search party several hours later bangs on sheets of tin to try and signal to the missing girls. “No wonder the bloodhounds lose the trail,” Lindsay’s journalist friend Phillip Adams remarked in a newspaper column, “For the girls aren’t lost on the rock. Like Alices stepping through the looking glass, they’re moving into another dimension.” A week later, the girl who heard the drums, Irma, is found high on the rock asleep, unharmed except for a few scratches, but with no memory of what became of her friends or their math teacher.

Readers who are paying attention note that a search party several hours later bangs on sheets of tin to try and signal to the missing girls. “No wonder the bloodhounds lose the trail,” Lindsay’s journalist friend Phillip Adams remarked in a newspaper column, “For the girls aren’t lost on the rock. Like Alices stepping through the looking glass, they’re moving into another dimension.” A week later, the girl who heard the drums, Irma, is found high on the rock asleep, unharmed except for a few scratches, but with no memory of what became of her friends or their math teacher.

Lindsay in real life claimed that clocks would not function near her, and friends confirmed that their watches would stop in her presence. In her memoir Time Without Clocks, she described her own hatred of the clock-bound life most people lead. There were few clocks at Mulberry Hill, the Lindsays’ home in Victoria. She didn’t even know her own birth date until she asked another journalist friend, Terence O’Neill, to help her research it. In his own confusion of chronology, Adams described that “Long before Einstein revealed his relativity theory, in which time ceases to be something solid and dependable and becomes elastic, Joan believed that it was somehow dreamlike, that yesterday is still with us while tomorrow is already here.” In reality, Joan was still a little girl when Einstein formulated his theory—but what’s a little time warp between friends?

The Missing Chapter

The more readers pressed Lindsay for details about her inspiration, the more she clammed up—and even complained at how people kept showing up uninvited at Mulberry Hill, to get answers. Yet her various coy allusions to a true story, and to real people concealed in her novel, kept readers digging.* Amid all the speculation by readers, there were rumors of a final chapter that had been cut from the novel prior to publication, which contained the answer to the mystery.

The rumors proved … entirely true. Although the “explanation” the missing chapter provided is one that few readers could understand, let alone accept. The missing “Chapter 18,” published in 1987 as The Secret of Hanging Rock (along with a couple critical commentaries), is one of the most fascinating and beautiful pieces of “paranormal fiction” I have ever read. And the story of how it came to be excised from the novel is just as interesting, and telling.

The novel as published chronicles various upheavals in the community following the girls’ disappearance. These include the re-exploration of the rock by the two young men who had last seen the girls, the recovery of Irma, the suicide of one of the other students (who the film suggests had been in love with the missing Miranda), and the descent into drink and finally suicide of the headmistress Mrs. Appleyard (played by Rachel Roberts in the movie), after several parents withdraw their daughters and their money from her school. The missing Chapter 18 does indeed return us to the Rock and to “what happened,” but it is nothing that would fit within the usual coordinates of a romantic mystery novel.

The novel as published chronicles various upheavals in the community following the girls’ disappearance. These include the re-exploration of the rock by the two young men who had last seen the girls, the recovery of Irma, the suicide of one of the other students (who the film suggests had been in love with the missing Miranda), and the descent into drink and finally suicide of the headmistress Mrs. Appleyard (played by Rachel Roberts in the movie), after several parents withdraw their daughters and their money from her school. The missing Chapter 18 does indeed return us to the Rock and to “what happened,” but it is nothing that would fit within the usual coordinates of a romantic mystery novel.

The trio of girls—the otherworldly beauty Miranda, the intellectual Marion (who gazed down on the picnickers like at ants), and the wealthy Irma—are on a high ledge, drawn toward a stone monolith that exerts a kind of spiral magnetic force, “pulling, like a tide.” Beyond it, the girls fall asleep briefly and then encounter a “clown-like figure” dressed only in her undergarments and boots—clearly the math teacher, Mrs. McCraw, whom Edith later recalled with embarrassment seeing coming up the hill in only her underwear while she was running down it. Yet the girls don’t recognize the woman—they are already in a dream-like state where reality has been transfigured.

Marion then gets the idea they should all discard their restricting corsets, which they toss off a precipice, only to see them hanging motionless in mid-air. The math teacher/stranger says “they are stuck fast in time,” at which one of the girls tells her “when you said that about time I had such a funny feeling I had met you somewhere. A long time ago.” The older woman replies, “Anything is possible, unless it is proved impossible. And sometimes even then.” She then asks for the girls’ names, even though she should know them, and notes she has forgotten her own name: Waving toward a bush, she says “I have apparently left my own particular label somewhere over there.”

It is a “trippy” exchange—indeed, like a group of people under the influence of a powerful hallucinogen. And it gets stranger. When the brainy Marion suggests they keep moving before the sun sets, the older woman utters further perplexities:

“For a person of your intelligence—I can see your brain quite distinctly—you are not very observant. Since there are no shadows here, the light too is unchanging.”

Irma was looking worried. “I don’t understand. Please, does that mean that if there are caves, they are filled with light or darkness? I am terrified of bats.”

Miranda was radiant. “Irma, darling—don’t you see? It means we arrive in the light!”

“Arrive? But Miranda … where are we going?”

“The girl Miranda is correct. I can see her heart, and it is full of understanding. Every living creature is due to arrive somewhere. …”

Which is when they see a hole open up before them:

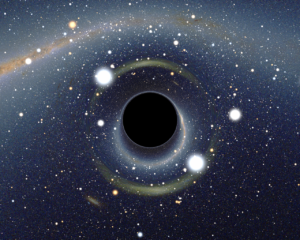

It wasn’t a hole in the rocks, nor a hole in the ground. It was a hole in space. About the size of a fully rounded summer moon, coming and going. She saw it as painters and sculptors saw a hole, as a thing in itself, giving shape and significance to other shapes. As a presence, not an absence—a concrete affirmation of truth. She felt that she could go on looking at it forever in wonder and delight, from above, from below, from the other side. It was a solid as the globe, as transparent as an air bubble. An opening, easily passed through, and yet not concave at all.

The “hole in space” fades out, after which they observe a snake descend down a physical hole below some boulders. The woman formerly known as Mrs. McCraw then confidently decides to lead the girls into the hole. She wriggles into it, undergoing a kind of transformation as she does so (“The thin arms, crossed behind the head with its bright staring eyes, became the pincers of a giant crab”)—followed by Marion and Miranda in turn. Then to Irma’s horror another boulder falls on the hole, sealing it off.

Irma had flung herself down on the rocks and was tearing and beating at the gritty face of the boulder with her bare hands. She had always been clever at embroidery. They were pretty little hands, soft and white.

So that is how Joan Lindsay originally ended her novel: with Hanging Rock itself devouring the girls and their teacher. In contrast to the matter-of-fact tone of the rest of the book, it is more like something out of Carlos Castaneda—or indeed, Lewis Carroll. As Yvonne Rousseau wrote in her commentary to this chapter, it also bears close rereading. Among other things, there is something punnily akin to dream in these strange events: Mrs. McCraw’s crab-transformation is into a kind of claw; the corsets that hang in midair were colloquially called “stays,” and stay in spacetime is what they do. It is a stunning vision of the Minkowski block universe.

Lindsay’s Time Slip

It is certainly significant that Lindsay had experienced at least one “time slip,” which made such an impression that she related the story to several friends. Probably in 1929, her husband Daryl had been driving her to another town, Creswick, to visit his mother, and on the way Joan saw something strange. One friend, John Taylor, recalled her story in his commentary to the missing chapter: “half a dozen nuns were running frantically across a field and climbing a fence. Her husband saw nothing. Puzzled, she asked her mother-in-law if there was a convent in the area. There had been, she was told, but it had burned down years earlier.”

Lindsay’s time slip in 1929 undoubtedly was a significant influence on her beliefs about time, but so was another, more famous time slip that dated to the same period her novel was set in. She confided to her friend Adam Phillips that her writing of Picnic had been very influenced by the book An Adventure, first published anonymously in 1911 by a pair of English academics, later revealed as Charlotte Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain, about an alleged shared time-slip experience while wandering the gardens of Versailles in 1901: The women reported seeing a number of people in anachronistic dress that they later determined must have been the ghosts of Marie Antoinette and her courtiers circa 1789, just before their deaths in the French Revolution.

Although it is the most famous time slip, Moberly and Jourdain’s account has also proven to be one of the least persuasive to critics. One critic chalked it up to costume parties an aristocrat was known to throw on the grounds; another, Lucille Iremonger, attributed it to a lesbian folie-a-deux between the two women (because lesbians, of course, are always hallucinating). The real problem is that weeks had elapsed after the women’s visit before they even conferred on what they had seen, and both seem to have experienced different things. There is no telling how much their memories of their first visit may have been shaped by the decade of research delving into the history of the Trianon garden and Versailles as well as their subsequent visits to the gardens, or how much their memories influenced each other. If there was a real time slip, it may have just been just one of them who experienced it, the other having adjusted her memory to conform with the notion of “something strange” occurring. At this point, there is no telling.

Although it is the most famous time slip, Moberly and Jourdain’s account has also proven to be one of the least persuasive to critics. One critic chalked it up to costume parties an aristocrat was known to throw on the grounds; another, Lucille Iremonger, attributed it to a lesbian folie-a-deux between the two women (because lesbians, of course, are always hallucinating). The real problem is that weeks had elapsed after the women’s visit before they even conferred on what they had seen, and both seem to have experienced different things. There is no telling how much their memories of their first visit may have been shaped by the decade of research delving into the history of the Trianon garden and Versailles as well as their subsequent visits to the gardens, or how much their memories influenced each other. If there was a real time slip, it may have just been just one of them who experienced it, the other having adjusted her memory to conform with the notion of “something strange” occurring. At this point, there is no telling.

Still, it made for an interesting book—one that was influential on many writers, including J.R.R. Tolkien (as Verlyn Flieger discusses in her book A Question of Time). But I think even more importantly, the edition that Lindsay is likely to have read, which was published in 1931, also included an introductory note by J.W. Dunne, the aeronautical engineer and precognitive dreamer whose 1927 book An Experiment with Time is probably the most important book ever written on the subject of precognition and its relation to the Einsteinian time-elastic universe. He writes that he was asked to comment on the scientific plausibility of the women’s account, and states that “if Einstein is right, the contents of time are just as ‘real’ as the contents of space. Marie Antoinette—body and brain—is sitting in the Trianon garden now.” More than anything in Moberly and Jourdain’s text, it is that line from Dunne’s note that surely exerted its effect on Lindsay when opening her Chapter 18:

It is happening now. As it has been happening ever since Edith Horton ran stumbling and screaming towards the plain. As it will go on happening until the end of time. The scene is never varied by so much as the falling of a leaf or the flight of a bird. To the four people on the Rock it is always acted out in the tepid twilight of a present without a past. Their joys and agonies are forever new.

“An Uncomfortable Style”

You will be right to ask about Chapter 18’s authenticity: A “missing chapter” to a nationally beloved novel turning up shortly after the death of the author should always be suspect. However, in this case, there does not seem to be any question of the text being a forgery, as there are living witnesses to the original manuscript with the chapter in place.

When Lindsay originally submitted her novel to her friend, publisher Andrew Fabinyi, he was enthusiastic; but he assigned it to a junior editor, Sandra Forbes, who felt uncomfortable about the ending. As described by Janelle McCulloch in her recent book Beyond the Rock, Forbes wrote in a letter to Lindsay: “I’m very doubtful about the last chapter. On the whole, would prefer to omit it altogether.” In an interview with McCulloch, Forbes asserted that the decision to cut the chapter had been agreed on by the author: “We all discussed it and it seemed the right thing to do.”

When Lindsay originally submitted her novel to her friend, publisher Andrew Fabinyi, he was enthusiastic; but he assigned it to a junior editor, Sandra Forbes, who felt uncomfortable about the ending. As described by Janelle McCulloch in her recent book Beyond the Rock, Forbes wrote in a letter to Lindsay: “I’m very doubtful about the last chapter. On the whole, would prefer to omit it altogether.” In an interview with McCulloch, Forbes asserted that the decision to cut the chapter had been agreed on by the author: “We all discussed it and it seemed the right thing to do.”

It is hard to know how to evaluate Forbes’ claim. Lindsay’s friend and literary agent John Taylor, to whom she entrusted the typed pages of the cut chapter in 1972 and who published it as The Secret of Hanging Rock in 1987, three years after her death, insisted that she intended it to be published; it was part of her original vision and clearly expressed spiritual truths that were important to her. “Certainly, she wanted Chapter 18 to appear,” Taylor wrote in his commentary to the chapter. “What artist wants to conceal an unflawed work?” Taylor claimed that despite her natural artistic wish not to excise part of her novel, she allowed herself to be persuaded by others: “She was meticulous in respecting the interests of those who were exploiting her work, and understood that it might have worked against those interests.”

Besides losing a very personal and important part of her story, the absence of the final chapter also had become a kind of negative Albatross for Lindsay by the time of her death. It left readers to concoct fictions of their own to solve the puzzle, and their demands for confirmation left her and her husband with little peace during their old age. Taylor wrote: “Although she knew perfectly well that the huge success of both book and film had a lot to do with the mystery of ‘what really happened’, she had moments of wishing she had published the final chapter and saved herself the pestering.” Lindsay gave Taylor the copyright to the final chapter after Weir’s film came out, “as part of her general horrified reaction to the flood of demanding inquiries” about the true fate of the girls. As her literary agent, it was Taylor’s job to deal with the constant questions.

Taylor, like Forbes, was not unbiased in the matter—he perhaps stood to gain from publishing the chapter—so we cannot be certain of his claims that Lindsay intended Chapter 18 to come out. Purely in terms of the bottom line, Forbes clearly made the right editorial decision, since the book would never have been as successful without the question mark it leaves in the reader’s mind. Taylor acknowledges this as well, keenly comparing the missing chapter to the Psalmist’s “stone rejected by the builders,” which becomes the cornerstone of the edifice. Chapter 18 is “the previously invisible foundation stone on whose absence the Australian film industry built itself.” The missing Chapter 18 is, he notes, “totally unfilmable.” Still, despite Forbes’ implication that the decision to cut Chapter 18 was mutual, it appears to have been a very ambivalent one for Lindsay.

Just as interesting as the chapter itself is the discomfort it aroused in her editor, Forbes. In another recent interview by Helen Goltz for the book No Picnic at Hanging Rock, Forbes recalled conversations with Taylor in 1984, after Lindsay’s death, about the possibility of publishing the missing chapter; she reiterated her earlier sentiments: “I didn’t like the final chapter, it was not written in the same style, it was an uncomfortable style and I don’t think the final chapter did the book any service to publish it.” Goltz herself seems to share Forbes’ discomfort with the chapter, agreeing with the decision to leave it out and finding it merely bizarre: “I suspect the reader will be more bewildered as to the outcome of the young women on reading The Secret of Hanging Rock.”

These are clearly not readers of science fiction, or the paranormal. Indeed, the core issue with Lindsay’s book is that in its original form it transgressed genres. Although Forbes may not have articulated it this way, Chapter 18 turned Picnic at Hanging Rock into SF, or some kind of supernatural Gothic mystery. Especially at the time (1967), those belonged to a low-level literary ghetto where, besides there being no literary respectability, there was also no money. As Jeffrey Kripal has shown in his books like Mutants and Mystics, the collective cultural discomfort with the paranormal experiences that have driven many writers of imaginative fiction reflects just how transgressive these experiences are.

These are clearly not readers of science fiction, or the paranormal. Indeed, the core issue with Lindsay’s book is that in its original form it transgressed genres. Although Forbes may not have articulated it this way, Chapter 18 turned Picnic at Hanging Rock into SF, or some kind of supernatural Gothic mystery. Especially at the time (1967), those belonged to a low-level literary ghetto where, besides there being no literary respectability, there was also no money. As Jeffrey Kripal has shown in his books like Mutants and Mystics, the collective cultural discomfort with the paranormal experiences that have driven many writers of imaginative fiction reflects just how transgressive these experiences are.

Lindsay was transgressive in other ways besides her time slips and her inhibitory effect on timepieces. Although married, she appears to have maintained life-long erotic friendships with two women, for instance. But like many women of her generation, she felt compelled to subordinate her own artistic and intellectual talents, to be a satellite of a talented, high-achieving man.

Sir Daryl Lindsay was one of the leading Australian painters of his generation, and then a high-profile director of Australia’s National Gallery for many years. The Lindsays led an enviable life surrounded by fascinating bohemians and celebrities. Through it all, Joan had little time or opportunity to express herself or develop her own unique talents as a writer, and she received little encouragement from Daryl. Another thing her life with Daryl suppressed, according to McCulloch, was her mysticism. She had long been drawn to the mystical and the paranormal—her friends all regarded her as a psychic—but avoided talking about these matters in front of Daryl. Although I can only conjecture, it is easy to imagine Daryl may have shared Forbes’ negative assessment of Chapter 18.

Precognitive Deconstruction

As readers of this blog know, I think misrecognized precognition is behind many paranormal experiences. In cases of “time slips,” for instance, there is typically a striking learning experience about the traversed landscape in the individual’s near future, and it typically matches the vision, whether or not it really matches historical reality. Lindsay’s vision was not of nuns going about their daily activities or doing any of the ordinary things nuns might have done in their lives, but of fleeing from something, and this acts as a “tracer” pointing directly to the story told by her mother-in-law later the same day. In other words, Lindsay’s vision was likely a premonition of a mental image formed upon hearing that exciting, entropic story, not a slip into the past. I suggest that “psychics” may often be people who tend more readily than others to map such future mental images onto their present sensory experience, almost like a kind of augmented-reality app. (One wonders how much of what gets diagnosed as psychosis is really precognition unrecognized.)

And as I argue in my book Time Loops, precognition is also the source of creative genius: Writers and artists are drawing on upheavals in their own futures, and this is particularly visible with visionary and genre writers—or those who barely manage to escape a genre pigeonhole through clever reframing or, in Lindsay’s case, editorial bowdlerization. Their lives and works often show evidence of bizarre causal tautologies or self-fulfilling prophecies. Lindsay, I believe, belongs to the club of highly precognitive writers, and her novel lends itself to a kind of precognitive rereading.

Consider: Picnic at Hanging Rock stages a traumatic disappearance—a group of schoolgirls go on a picnic and come back minus three, and minus one math teacher—and then describes the ripple effects of that disappearance. While there was no actual disappearance of schoolgirls at Hanging Rock either around the turn of the century or in the 19-teens when Lindsay attended Clyde School, there was a traumatic disappearance in Lindsay’s near future when she wrote her manuscript: none other than the cutting of her final chapter, with its beauty and strangeness and its mathematical-physical musings.

Consider: Picnic at Hanging Rock stages a traumatic disappearance—a group of schoolgirls go on a picnic and come back minus three, and minus one math teacher—and then describes the ripple effects of that disappearance. While there was no actual disappearance of schoolgirls at Hanging Rock either around the turn of the century or in the 19-teens when Lindsay attended Clyde School, there was a traumatic disappearance in Lindsay’s near future when she wrote her manuscript: none other than the cutting of her final chapter, with its beauty and strangeness and its mathematical-physical musings.

The cut was traumatic because that final chapter was the most personal statement of Lindsay’s spiritual and scientific beliefs about time. Yet as everyone agrees and Lindsay even came to agree, the novel never would have been popular had the cut not been made. Taylor confirms it was thus a source of deep ambivalence for Lindsay. These are precisely the kinds of mixed emotions that characterize precognition-worthy experiences.

We could thus read the complete dream-inspired novel as originally written in late 1966, with its final chapter, as being about the subsequent editorial cut of its final chapter and the aftereffects of that cut. In the novel, Appleyard College is beset by unwelcome, curious visitors in the aftermath of the disappearance. Mulberry Hill, the Lindsay’s home, was beset by unwelcome, curious visitors in the aftermath of the novel’s publication and especially of the movie: people wanting to find out the truth.

As it happens, the loss of the spiritual chapter, Chapter 18, wasn’t a complete excision, however, and some of the novel’s peculiarities assume a precognitive significance in light of this fact also.

One of the three girls, Irma, who has heard the beating of drums and then witnesses the disappearance of her friends into the hole, is found alive and returns to the school near the end, but without any memory of what happened. It so happens that the passage about the beating of drums (which some readers like Taylor and Phillips thought was a clue that the author was playing tricks with time) originally appeared in Chapter 18 (that is, in correct chronology). Lindsay preserved it and re-placed it, along with a few other passages, earlier in the book when she agreed to cut the rest of the final chapter. The opening paragraph, about the events being frozen in time, was also retained and re-placed to an earlier chapter. In other words, fragments of the missing chapter do appear throughout the book as published, because Lindsay saw fit to have them “rescued” from the editorial edict. The rescue and return of Irma might thus be “prophetic” of the rescue and return of these fragments.

So I suggest—though obviously it would be impossible to prove—that Lindsay’s week of dreams in the winter of 1966, which she feverishly spent her days writing into the novel that made her famous, represented “the whole package” of what was about to happen in her life as a direct result of writing those dreams down—in other words, a time loop. The core thread of prophetic jouissance is a kind of reward and excitement. What could be more exciting than writing an amazing mystery novel and then becoming widely known and admired for it (not to mention the royalties and movie rights)? But like most or all precognitive experiences, it also pointed to the survival of a loss, a cut, a sacrifice that needed to be made for that success, and it was the sacrifice of the bulk of the most radical, personal, and spiritual part of what Lindsay had written.

Fans, I suggest, were thus looking in the wrong direction for the “reality” behind Lindsay’s mystery. The story—a party that traumatically loses a few members and provokes a desperate search, as well as other ripple-effects—rather strikingly anticipates the fate of the novel itself: the traumatic disappearance of its final chapter, leaving everyone “hanging” as to its meaning, and provoking widespread obsessive search for the “true story” underlying it, as well as frustration by the author at having had her most important convictions silenced. Lindsay no doubt did want people to see it, yet felt prevented—silenced, or indeed, castrated.

It is incredibly Freudian, really. A castration is a kind of sacrifice or threatened sacrifice that keeps things within their proper limits, a warning or punishment for transgression. In the child’s imagination, it leaves behind a “hole.” It is also Einsteinian: Although the possibility of gravitational singularities had been described in the upper echelons of astrophysics for years, they did not enter the public consciousness until, wait for it, 1967, when the term “black hole” was coined. Lindsay’s “hole in space” image was, again, written late the previous year.**

It is incredibly Freudian, really. A castration is a kind of sacrifice or threatened sacrifice that keeps things within their proper limits, a warning or punishment for transgression. In the child’s imagination, it leaves behind a “hole.” It is also Einsteinian: Although the possibility of gravitational singularities had been described in the upper echelons of astrophysics for years, they did not enter the public consciousness until, wait for it, 1967, when the term “black hole” was coined. Lindsay’s “hole in space” image was, again, written late the previous year.**

Most significantly, the girls’ stunning vision high atop the Rock, of a convex absence that was also a presence, which they could not stop gazing at with pleasure, seems symbolic of the role of the spiritual/paranormal itself in and around the book: The hole is the final chapter in which it is embedded, the excised spiritual core of the novel, the really fascinating part, the solution to the mystery, which everyone wanted to see but which no readers got to see, a presence that became an absence simply because it made a cautiously realist editor uncomfortable.

No Party Is More Important than the Hole

In his classic manual, The Art of Dramatic Writing, Lajos Egri tells a story about the sculptor Rodin and his famous massive sculpture of the writer Balzac. When he had finished and showed it to a group of his pupils, all they could do was rave at how exquisitely he had rendered the writer’s hands, held out in front of his body. According to Egri, this enraged the sculptor, who grabbed an axe and chopped off the hands. “I was forced to destroy these hands because they had a life of their own. They didn’t belong to the rest of the composition. Remember this and remember it well,” he exhorted his students, ”No part is more important than the whole!”

I had always remembered this story about Rodin, from when I had read Egri’s book in college. And since it seemed so appropriate to the story of Joan Lindsay and her Chapter 18, I returned to it for the sake of writing this chapter. I did not have a copy, so I was forced to search the Internet for the quote I was seeking—and that search revealed quite quickly that what Egri had written was not true. Rodin, at least as far as I could determine, never took an axe to his sculpture of Balzac to break off its distractingly wonderful hands. It was merely a bit of artful (and thus memorable) dramatic writing. The reality is both less dramatic but also more revealing—and indeed, even more illustrative of the point I am trying to make about Joan Lindsay’s excised Chapter 18.

I had always remembered this story about Rodin, from when I had read Egri’s book in college. And since it seemed so appropriate to the story of Joan Lindsay and her Chapter 18, I returned to it for the sake of writing this chapter. I did not have a copy, so I was forced to search the Internet for the quote I was seeking—and that search revealed quite quickly that what Egri had written was not true. Rodin, at least as far as I could determine, never took an axe to his sculpture of Balzac to break off its distractingly wonderful hands. It was merely a bit of artful (and thus memorable) dramatic writing. The reality is both less dramatic but also more revealing—and indeed, even more illustrative of the point I am trying to make about Joan Lindsay’s excised Chapter 18.

By the time he was planning his statue of Balzac, Rodin had come to care little about public opinion—about his works or anything else—and his plan for his statue was to depict the writer in the act of masturbating, which Rodin knew had been part of the writer’s creative process. Studies for the final sculpture show the writer gripping the end of his thrust-out member. But his need to satisfy the Société des Gens de Lettres that had made the commission no doubt contributed to Rodin’s self-bowdlerization of his original vision, placing Balzac’s hands under his robe, where it will be unclear to all but the dirtiest-minded viewer (or those who know of Balzac’s habits) what his hands are up to. In the end, it didn’t matter—Rodin lost the commission, his sculpture languished, and it wasn’t finally cast in bronze until long after his death. (It is now on prominent display at the corner of Boulevard du Montparnasse and Boulevard Raspail in Paris.) Undoubtedly, that would not have happened had Rodin remained true to his original vision; it would ultimately have been censored, kept hidden away.

Why did Egri tell his story the way he did? Did he misremember the true story? Was his unconscious so threatened at a statue showing masturbation, or of the “castration” of such a vision, that his memory twisted Balzac’s phallus into hands?

The paranormal is “obscene” in very much the same way as—although perhaps for different reasons than—Rodin’s original vision for his statue of Balzac. Its fate is to be marginalized and denied—erased—and then to haunt us in the way the repressed, per Freud, always returns. Moreover, even when a cultural authority reincorporates what has gone missing, it will often be in a distorted, “safe,” and untrue-to-life fashion, almost as though the real thing has a force field around it, leading to distortion and denial.

The fate of Joan Lindsay’s Chapter 18 is the fate of the paranormal itself in our culture: to be excised, “cut,” from the rest of life in order for everything to add up and not challenge our conventional views of time and causation. We would rather be faced with a traumatic disappearance—a kind of literary castration—and then play the game of hunting for a sensible, materialist cause (the girls were murdered, they fell down a crevasse, etc.) than confront a baffling, science-fictional vision like what Lindsay had presented in her original draft, based on her own intuitions about the nonexistence of time and the living mysteries of the Australian landscape.

Notes:

* Although no schoolgirls seem to have really gone missing at Hanging Rock around the turn of the century or later, the obsessive search for sources for Lindsay’s story did turn up the likely basis for her many coy comments that “something did happen.” According to McCulloch, during her attendance at Clyde School in the mid-19-teens, Lindsay had been editor of the school’s paper, The Cluthan. A couple years after she left the school, in 1919, a math teacher named Miss McCraw published in The Cluthan an account of a field trip of the school’s Camera Club to Hanging Rock at night, to take moonlit pictures. They departed, Miss McCraw described, as a row of “freshly clad maidens” yet returned, after difficult scrambling over rocks and brambles, in a disheveled state: “sorry objects.” The field trip evidently became a source of rumor and mild scandal among students in subsequent years.

** Particularly prescient was Lindsay’s description of what a “hole in space” might look like. For nearly five decades, until Christopher Nolan’s 2014 film Interstellar (which was science-advised by black hole expert Kip Thorne), black holes were confusedly depicted in art and science fiction films as concave whirlpools in space rather than as convex spheres. Her description of a convex hole in space not only anticipated black holes, in other words, but also fast-forwarded to a revolution in black hole iconography that was far off in the future.

Sources:

Anon., An Adventure (with a note by J.W. Dunne)

Phillip Adams, The Unspeakable Adams

Lajos Egri, The Art of Dramatic Writing

Verlyn Flieger, A Question of Time

Helen Goltz, No Picnic at Hanging Rock

Lucille Iremonger, The Ghosts of Versailles

Jeffrey J. Kripal, Mutants and Mystics

Joan Lindsay, Picnic at Hanging Rock

Joan Lindsay, The Secret of Hanging Rock (with commentaries by John Taylor and Yvonne Rousseau)

Joan Lindsay, Time Without Clocks

Janelle McCulloch, Beyond the Rock

Terence O’Neill, “Joan Lindsay: A Time for Everything” (The LaTrobe Journal no. 83, May 2009)

Yvonne Rousseau, The Murders at Hanging Rock

Transcendentally amazing blog post. Bra-EFFING-vo>

I’m sure lots of folks will start banging the David Paulides/MISSING 411 drum, but—as those folks often do—they’ll be missing the deeper cultural touchstones.

I can’t help but see shades of the faerie host in the prominence of boulder fields (a cross-cultural fae environ), as well as the banging on tins—loud commotion is a common prescription for paranormal disappearances, from Wales (church bells) to Japan (drums). The desire to remove clothing is also notable, echoed not only in the M411 studies but also English folklore, where the inversion of clothing could facilitate a return to the human realm. And—needless to say, but I shall anyway—Lindsay’s difficulty with clocks and watches is echoed by countless near death experiencers and self-described alien abductees.

Again—bang up job on this.