The Passion of Einstein: Light, Spacetime, and the Holy Grail

In David Lindsay’s bizarre Gnostic allegory A Voyage to Arcturus, space travel is accomplished by means of “back light”—light rays that strive to return to their origin. A bottle of back light gathered through a telescope aimed at Arcturus is used to pull a small ship and its passengers from an observatory in Scotland up to that distant star system.

If you think about it, “back light” does exist in some sense, and is inseparable from light itself. We are used to hearing how light from a star took X many years to reach our eyes, and thus, when looking at that star, we are seeing into the past. In the case of Arcturus, which is 36.7 light years distant, I see photons that started their journey across space when I was ten years old. This truism that we look into the past when we gaze into space tends to reinforce the dualistic separateness of subject and object … but there is another way of looking at it.

If you think about it, “back light” does exist in some sense, and is inseparable from light itself. We are used to hearing how light from a star took X many years to reach our eyes, and thus, when looking at that star, we are seeing into the past. In the case of Arcturus, which is 36.7 light years distant, I see photons that started their journey across space when I was ten years old. This truism that we look into the past when we gaze into space tends to reinforce the dualistic separateness of subject and object … but there is another way of looking at it.

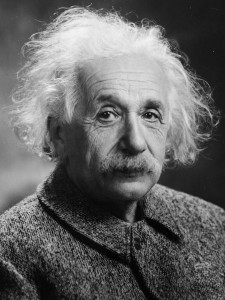

Light is the medium of communication of events and forces, and thus, of causality itself. Einstein grasped that If you tried to run alongside light, it would seem to outpace you by the same amount no matter how fast you were running. But if you were light, everything would be in a state of eternity and immediacy. Really, there are no objects, only relationships defined by interacting electromagnetic quanta, which is not a “communication of information” but, seen from the perspective of higher dimensions, something much more. Light really “goes both ways” or, more correctly, doesn’t go at all. There is nowhere to go, from the point of view of light.

Thus when I see Arcturus there in the sky, we are really united. Those photons that “left” Arcturus nearly four decades ago and are now reaching my eye are, when viewed four- or more-dimensionally, the actual touch of the star and my eye, reaching across purely illusory decades. Within such a perspective, I am potentially in communion with all places and all times. I touch Arcturus at the same time that it touches me. (Moreover, given the Uncertainty Principle, my seeing and registering those photons is actually affecting that star 36.7 years ago, in some tiny subatomic way. In a butterfly-effect universe, ought those tiny subatomic effects of distant observation not add up to substantial effects over the course of cosmic history?)

Thus when I see Arcturus there in the sky, we are really united. Those photons that “left” Arcturus nearly four decades ago and are now reaching my eye are, when viewed four- or more-dimensionally, the actual touch of the star and my eye, reaching across purely illusory decades. Within such a perspective, I am potentially in communion with all places and all times. I touch Arcturus at the same time that it touches me. (Moreover, given the Uncertainty Principle, my seeing and registering those photons is actually affecting that star 36.7 years ago, in some tiny subatomic way. In a butterfly-effect universe, ought those tiny subatomic effects of distant observation not add up to substantial effects over the course of cosmic history?)

We may think of ourselves as a human-shaped bodies here where we are in space and nowhere else, but from the point of view of light we are pulled apart in every possible direction, and thus have the shape of the universe. We are dissolved in spacetime. Thus the simple concept of “world lines”—of our present selves as “sections” of a worm moving through a static glass football—is really mistaken, as I argued in my previous post on eternalism. Not only are our “worms” impossibly fuzzy, extending to all points in spacetime, they also shift and shimmer and change depending on your vantage point. There’s no one history but infinite variants depending on one’s point of view.

Time, the fourth dimension, is not fixed, but is subject to the rule of light and thus, I suggest, subject to crucial “traumatic” vagaries arising from the fact that light obeys a fixed speed limit. Yet at the same time, by being the very medium of cosmic causal communion, light offers its own “salvation.” In this dual nature, light, the shaper of Time, is very much like the “blood of Christ” in the Christian imagination.

Dick Symbols

In his Exegesis (and its fictionalized version, Valis), Philip K. Dick kept returning to the Grail kingdom from Wagner’s opera Parsifal to explain his emerging Gnostic conceptualization of the relationship between Platonic forms and Time, or, between cold crystalline history (the 4-D football of Minkowski or Alan Moore, previous post) and a hyperfootball universe in which salvation is possible.

When the young knight (Parsifal) is brought to the Grail castle, he notices that he is walking but doesn’t seem to move. The chief Knight of the Grail explains that, “Here, my son, time turns into space.” The Grail itself is what Dick calls a “common constituent,” a node of eternity around which history circles and that, as a result, has salvific power—just like the Jesus fish around a young woman’s neck that triggered his mystical experience (or psychotic break, depending on your interpretation). Dick writes in his Exegesis that “This is how … the Eucharist works, how through the sacrament ‘time is overcome’—normal time becomes space … My 5-D realm … is the realm of Kosmos Noetos, hence logos, hence the realm of Christ.”

When the young knight (Parsifal) is brought to the Grail castle, he notices that he is walking but doesn’t seem to move. The chief Knight of the Grail explains that, “Here, my son, time turns into space.” The Grail itself is what Dick calls a “common constituent,” a node of eternity around which history circles and that, as a result, has salvific power—just like the Jesus fish around a young woman’s neck that triggered his mystical experience (or psychotic break, depending on your interpretation). Dick writes in his Exegesis that “This is how … the Eucharist works, how through the sacrament ‘time is overcome’—normal time becomes space … My 5-D realm … is the realm of Kosmos Noetos, hence logos, hence the realm of Christ.”

People have imagined that somehow Wagner anticipated Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity and its equivalence of space and time. Indeed, similar objects (like Dick’s common constituents) do have a central place in cosmology, as singularities—places where Time breaks down under the enormous mass/gravitational force of a collapsing star and its subsequent ravenous hunger.

Theoretically there is no history inside the singularity of a black hole, and I think it has also been proposed that there may be no difference between different singularities—the guts of all black holes might all, really, be the same no-place, out of Time and out of Space. Hence the conceptual linkage of black holes to hyperspace, wormholes, and time travel—even the vicinity or edges of such objects could draw together distant regions of space and time and thus provide shortcuts between them. In the wonderful novel Fiasco by Stanislaw Lem, a zone of retarded time near a black hole, which he dubs a “bradychronality,” is used to synchronize the histories of an interstellar mothership and its exploration vessel; a similar plot device is used in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar.

Theoretically there is no history inside the singularity of a black hole, and I think it has also been proposed that there may be no difference between different singularities—the guts of all black holes might all, really, be the same no-place, out of Time and out of Space. Hence the conceptual linkage of black holes to hyperspace, wormholes, and time travel—even the vicinity or edges of such objects could draw together distant regions of space and time and thus provide shortcuts between them. In the wonderful novel Fiasco by Stanislaw Lem, a zone of retarded time near a black hole, which he dubs a “bradychronality,” is used to synchronize the histories of an interstellar mothership and its exploration vessel; a similar plot device is used in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar.

Wagner’s Grail kingdom, with its bleak repetitive ritual and its grim knights who seem trapped in amber, is like one of Lem’s black-hole bradychronalities. Wagner apparently used elaborate sets and choreography to visually convey this sense of movement-in-immobility. (I have never seen Parsifal performed but I have been near a black hole many times, and frustratingly walking without seeming to move is exactly what it is like.)

Sublime Objects

Things not unlike Dick’s “common constituents” also have a central place in the Lacanian-Hegelian philosophy of Slavoj Žižek, as what he calls “sublime objects”: inaccessible, simultaneously fascinating and threatening or even horrifying remnants of trauma that rupture the symbolic universe—the universe of meaning—but also anchor it in place, just like the imperious supermassive black holes at the heart of galaxies, around which all stars circle in stately obedient procession.

In the vicinity of a sublime object, history gets caught in endless orbital loops of fixation and repetition, thus they form the nuclei of individual fetishes and neurotic symptoms as well as religious rituals and political ideologies. Žižek’s classic example is the remains of the Titanic, which spookily fascinated viewers when the wreck was discovered in the early 1980s. Other examples would be the ruins of the World Trade Center towers after 9/11, or the ruins of Auschwitz/Birkenau; both represent the site of a horrible trauma, yet both are also repeatedly revisited and “enjoyed” in a kind of pathological-obsessive way.

In the vicinity of a sublime object, history gets caught in endless orbital loops of fixation and repetition, thus they form the nuclei of individual fetishes and neurotic symptoms as well as religious rituals and political ideologies. Žižek’s classic example is the remains of the Titanic, which spookily fascinated viewers when the wreck was discovered in the early 1980s. Other examples would be the ruins of the World Trade Center towers after 9/11, or the ruins of Auschwitz/Birkenau; both represent the site of a horrible trauma, yet both are also repeatedly revisited and “enjoyed” in a kind of pathological-obsessive way.

The real tendency of subjective time to slow down during crises and disasters, as well as the Freudian neurotic compulsion to engage in repetitive behavior around our traumas, suggests that the connection between weighty trauma and the gravity that bends spacetime may be more than metaphorical. Milan Kundera keyed in on this with his meditation on lightness and weight in The Unbearable Lightness of Being: Things are light and insubstantial if they never repeat or return; only if they repeat are they consequential and serious; cosmology reverses this causal priority of weight and repetition (or spacetime curvature): Only if events are heavy (like a trauma) do they cause things to go in circles or repeat. But indeed, both perspectives are fine, because in the vicinity of such a “heavy” formation, causality breaks down and there is no single temporal dimension, no before and after; the future causes the past as much as the past causes the future.

Sublime objects, the material form taken by the condensed compacted jouissance or “enjoyment” at the heart of personal and collective symptoms, are the same as the sacramental formations (common constituents) that give structure to Dick’s orthogonal time. Dick suggests it is not simply that forms repeat and exist in some kind of spacetime resonance with each other (as in Rupert Sheldrake’s theory of morphic fields); it is that the Jesus fish around the neck of a young woman in Orange County, CA in February 1974 is really in some sense the same Jesus fish as one worn by a secret Gnostic Christian in first century Syria.

Sublime objects, the material form taken by the condensed compacted jouissance or “enjoyment” at the heart of personal and collective symptoms, are the same as the sacramental formations (common constituents) that give structure to Dick’s orthogonal time. Dick suggests it is not simply that forms repeat and exist in some kind of spacetime resonance with each other (as in Rupert Sheldrake’s theory of morphic fields); it is that the Jesus fish around the neck of a young woman in Orange County, CA in February 1974 is really in some sense the same Jesus fish as one worn by a secret Gnostic Christian in first century Syria.

For most of the medieval and later writers who penned romances about knights seeking the Holy Grail, that object is precisely such a sublime, “out of time and sense” object, specifically because it implicitly holds Christ’s saving blood—the remnant or leftover of a primal trauma, which is also the only thing that (according to medieval Christianity) can save us. In fact, throughout his prolific career, Žižek, like Dick, has also continually used Wagner’s Parsifal to illustrate his theory. In the Grail King Anfortas’s realm, history has slowed to halt, circling repeatedly in the warped spacetime of obsessive pleasurable-painful jouissance, symbolized by the chronically festering wound on his thigh, which can only be cured by the spear that caused it—the spear that impaled Christ as he hung on the cross and is now possessed by Anfortas’s enemy, the evil wizard Klingsor.

The Flickering Grail

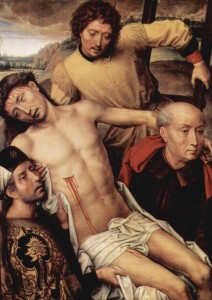

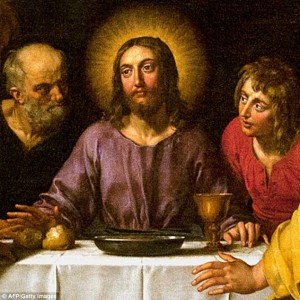

The central Christian “saving trauma” is of course Christ’s martyrdom in Jerusalem. The genius of the early Grail writers was to more clearly draw out the connection, only latent in the canonical Gospels, between Jesus’s blood ingested by his disciples at the Last Supper and the blood Christ shed on the Cross a couple days later. The romances “flicker” about which object this cup is: the cup the disciples drank from, which became symbolically the Eucharist cup in the Mass, or the cup used by Joseph of Arimathea to collect Christ’s blood after his crucifixion, when his body was lowered from the cross. The latter scene, the “Deposition,” does not appear in the canonical Gospels but in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, which was popular at the time.

The central Christian “saving trauma” is of course Christ’s martyrdom in Jerusalem. The genius of the early Grail writers was to more clearly draw out the connection, only latent in the canonical Gospels, between Jesus’s blood ingested by his disciples at the Last Supper and the blood Christ shed on the Cross a couple days later. The romances “flicker” about which object this cup is: the cup the disciples drank from, which became symbolically the Eucharist cup in the Mass, or the cup used by Joseph of Arimathea to collect Christ’s blood after his crucifixion, when his body was lowered from the cross. The latter scene, the “Deposition,” does not appear in the canonical Gospels but in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, which was popular at the time.

I think we can really see the Grail as both objects simultaneously, and that its atemporal “absurdity” is essential to the salvific nature of Christ’s blood: How could the blood shed on the Cross have gotten into the cup of the Last Supper other than by having traveled back in time? Christ’s blood is either made of tachyons (hypothetical faster-than-light particles that most physicists currently reject) or is, in effect, outside of linear Time altogether. Only if Christ’s blood is outside of Time and Cause does it make sense that the cup that once ever held it must have always held it and will keep holding it eternally—and there is just one thing known to physics that has those properties: The blood of Christ is, in effect, light.

We see then that, from a Gnostic point of view, Christ’s passion isn’t about anybody called Christ. It is about light and matter and space and time—in other words, causality itself, the very “order of things.” From the fifth-dimensional viewpoint of Dick and Wagner, Christ’s Passion on the cross is kind of solidified, four-dimensional hieroglyph of nothing other than Einstein’s theory of Relativity. Light, like Christ’s saving blood or the Grail that holds it, is unattainable, always at the same distance from us (as long as we are in our fallen, darkened state), yet it is also the very medium of cosmic communion that can save us. (It is no accident, I think, that Lacan also described the Real, the home of enjoyment, as something that is always the same distance from us despite whatever efforts we make to approach or get distance from it: It’s always, he said, “glued to our heel.”)

We see then that, from a Gnostic point of view, Christ’s passion isn’t about anybody called Christ. It is about light and matter and space and time—in other words, causality itself, the very “order of things.” From the fifth-dimensional viewpoint of Dick and Wagner, Christ’s Passion on the cross is kind of solidified, four-dimensional hieroglyph of nothing other than Einstein’s theory of Relativity. Light, like Christ’s saving blood or the Grail that holds it, is unattainable, always at the same distance from us (as long as we are in our fallen, darkened state), yet it is also the very medium of cosmic communion that can save us. (It is no accident, I think, that Lacan also described the Real, the home of enjoyment, as something that is always the same distance from us despite whatever efforts we make to approach or get distance from it: It’s always, he said, “glued to our heel.”)

Why is light a “trauma” for causality? Because of its fixed speed limit. Einstein’s famous “train-car” thought experiments must describe the state of affairs on even a subatomic scale: Electromagnetic radiation emitted from a given source at a given time reaches different “receiving” particles at slightly different times, meaning that causality itself is “warped” at the most fundamental level. One particle must have a different “story” of reality than the story told by a neighboring particle. This is why the luminiferous fuzz of our world-worms is in a constantly flickering either/or or both/and state; by extension the whole universe is multiple, shimmering, contradictory, and radically indeterminate or open-ended.

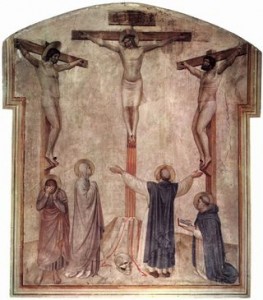

It is tempting to see the two thieves crucified along with Christ (described in Luke as well as some of the noncanonical gospels)—one who repents and follows the savior to heaven, and one who does not repent and goes to hell—as a figuration of light’s parallactic nature: That it separates, divides reality from itself, as much as it, on another level, unifies.

It is tempting to see the two thieves crucified along with Christ (described in Luke as well as some of the noncanonical gospels)—one who repents and follows the savior to heaven, and one who does not repent and goes to hell—as a figuration of light’s parallactic nature: That it separates, divides reality from itself, as much as it, on another level, unifies.

The Virtuality of Time and Space

Kant saw Time and Space as embedded structures in our brains, not as actual realities, and this helped pave the way for science to question the objective solidity and stability of the material world. As the Buddhists have always said, “nothing exists”—there is no stable self, no objective world of events. Žižek would agree, saying that Time itself (or history) is a perspective mistake, something purely virtual and nonexistent. There is only a structure of meaning which always changes “in retrospect”—which really just means, changes depending on your point of view.

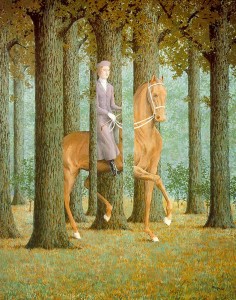

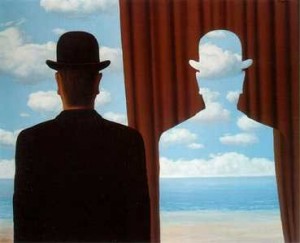

Žižek’s name for what Buddhists call “no self” is parallax. We literally see from two slightly different places, as well as always interpreting the world within rival incommensurable symbolic frameworks. For Žižek, though, the sense of stable reality is not something undercut by parallax, but actually created by it. The Real is an “optical illusion” created by a constant alternation between slightly divergent vantage points.

Žižek’s name for what Buddhists call “no self” is parallax. We literally see from two slightly different places, as well as always interpreting the world within rival incommensurable symbolic frameworks. For Žižek, though, the sense of stable reality is not something undercut by parallax, but actually created by it. The Real is an “optical illusion” created by a constant alternation between slightly divergent vantage points.

Recent neuropsychological research has revealed how parallax may work to create the illusion of Time: The sense of the now as having a duration arises from a resonance between slightly temporally offset “functional moments”; the resulting mini-Now or “experienced moment” (lasting 2-3 seconds) along with the slightly longer-duration function of working memory is what enables us to understand language and experience music, for example: building up “chords” of meaning from sequential sounds, perceptions, and thoughts that the brain binds together and unifies into a coherent whole. The ongoing juxtaposition of temporally offset experiences creates the illusion of Time as a dimension having its own volume or extension.

Examining mental activity in meditation reveals that the illusion of self or self-identity arises from a similar process, the constant automatic generation of imaginary representations of our experience—the “autosymbolization” function of the ongoing hypnagogia usually operative just underneath conscious awareness. These images spun off from successive moments of perception (also about every 2-3 seconds) hover over reality like ghosts, an imaginary “I” seeing as well an imaginary gaze seeing me seeing, etc., as well as forming the nuclei or seeds for trains of thoughts. These virtual representations give a Parmenidean sense of permanence and persistence (or at least, viscosity) to the Heraclitean river.

It seems like something analogous could be operative on even the “informational” (really, communal) Quantum world of matter, where the “flicker” or juxtaposition of subtly different realities (think Christ’s two thieves traveling in different directions) might generate what we interpret as the world’s material solidity. Remember that, optically, shifting among multiple points of view is what gives the world its apparent dimensionality—the 2-dimensional visual field (image) becomes 3 dimensional (volume) under parallax. By extension, the 3 dimensions of volume may (under “hyperparallax”) become 4 dimensional—not as Time, but as mass.

Mass could in other words be a “special effect” or illusion arising from objects’ noncoincidence with themselves on a fundamental material level, due to the fact that light (and thus causality) is a Constant with a speed limit. Perhaps mass could be thought of as the provisional “agreement” arrived at by all those confused/disputing subatomic particles who, like Einstein’s train passengers, see the world slightly differently depending on exactly how far along the track they are.

Mass could in other words be a “special effect” or illusion arising from objects’ noncoincidence with themselves on a fundamental material level, due to the fact that light (and thus causality) is a Constant with a speed limit. Perhaps mass could be thought of as the provisional “agreement” arrived at by all those confused/disputing subatomic particles who, like Einstein’s train passengers, see the world slightly differently depending on exactly how far along the track they are.

According to General Relativity, mass curves Space, and this curvature gives rise to Time. But it seems we could also think of mass as the “flip side” of Time (or of the Bergsonian “duration” and Heraclitean flux that we interpret as Time): Duration, transitoriness, and change arise, with mass, as a way for particles to resolve their “cognitive dissonance” over relativistic absurdities.

If that is the case, the “fourth dimension” would really be a kind of circular (you might say “ouroboric”) return from 3 dimensions back to 2, and thus our ordinary “fallen” sublight world would exist in a fractional dimensionality somewhere between 2 and 3. This would correspond well to Gerard ‘t Hooft’s holographic theory (which I discussed in my post on anamorphosis), which posits a flat, 2-dimensional spacetime at high energies as the baseline state from which the third dimension is an atypical, illusory—you might say “fallen”—condition.

The Fall of Spirit into Matter

The quanta carrying causal information exist out of time and space in some sense because they are time and space. The apparent space between them, the Void, may really be an illusion. The causal openness (or contingency) of the world, the very fact that things depend or differ and thus that history is not fixed (as in a glass football), is experienced as the spread-outness of the universe in both Space and Time. You might say that the inconceivable scale of the universe reflects the mindboggling or even frightening degree of its causal open-endedness, the degree to which “it depends” or, as Kundera put it, “It could just as easily be otherwise.”

In the same way, enjoyment, the “only substance” acknowledged by Lacan’s radically anti-materialistic version of psychoanalysis, is atemporal and acausal, and it is experienced as painful or pleasurable depending on whether it is represented and conceptualized—that is, pinned to symbols—or not. This is analogous to how particles’ position or velocity become real only when observed/measured, otherwise existing as waves, functions of pure probability and possibility.

The Cross itself helps us understand this. What had been an ancient pre-Christian symbol of matter was “conveniently” adopted by history (or at least, the Gospel-writers) as the mode of Christ’s execution, and it has since become something like our ur-symbol of symbolism itself. Besides painfully fastening the Son of God to matter, the Crucifixion thus depicts the basic process whereby, as Žižek put it, “the subject is fastened, pinned to a signifier that will represent him for the Other” and, more basically, the suffering that arises from fixing the volatile flux of experience with symbols, words, and concepts.

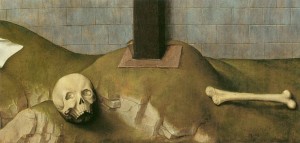

In medieval Christian folklore, the Cross was as atemporal/acausal as the blood spilling from Christ’s wounds: It was said to be hewn from the wood from the Garden of Eden, and paintings always showed the skull of Adam at its base. The fragments of the “True Cross” that circulated as priceless relics in the Middle Ages were spiritually potent (and economically valuable) sublime objects. In a sense, Christ has always been nailed to the One True Cross he was nailed to, as a kind of endlessly circular/tautological (and thereby Real) emblem of what Gnostics called the “fall of spirit into matter.”

In medieval Christian folklore, the Cross was as atemporal/acausal as the blood spilling from Christ’s wounds: It was said to be hewn from the wood from the Garden of Eden, and paintings always showed the skull of Adam at its base. The fragments of the “True Cross” that circulated as priceless relics in the Middle Ages were spiritually potent (and economically valuable) sublime objects. In a sense, Christ has always been nailed to the One True Cross he was nailed to, as a kind of endlessly circular/tautological (and thereby Real) emblem of what Gnostics called the “fall of spirit into matter.”

The blood that spilled and still spills from Christ as a result of this fixation both to matter and symbolism (which may be the same thing) is really pure enjoyment, and it may be both the cause of our suffering and our salvation depending on whether or not we embrace it—that is, whether we are the “good thief” asking to be remembered by Christ (and thus being saved) or are the unrepentant “bad thief” unwilling to give up our concepts and thus bound for eternal suffering. As any Buddhist would explain, “no self” is excruciating trauma from the standpoint of our clung-to symbolic/conceptual ego-worlds (i.e., “the unbearable lightness of being”), but it is bliss when our symbols are given up within the Real of meditation or nondual mystical experience.

Enjoyment Versus Consciousness

The Grail has always been the symbol of this interconversion not only of Time into Space (as Wagner and Dick understood) but, firstly of Enjoyment into Time. After all, what is the Grail/Eucharist Cup but the vessel that changes wine into Christ’s blood—symbolically expressing the changing of mundane convivial enjoyment (as at a dinner party) into the very traumatic/saving stuff of salvation and history? Because time flows in both directions or simply doesn’t exist in the vicinity of the Real, the opposite conversion is also possible.

You could also say that linear non-reversing Time is tantamount to lost or displaced (past/future) enjoyment. The curvature or distortion of Kantian categories (Space and Time) generates enjoyment, which we displace and symbolically domesticate as a linear causal progression and log/accession in our memorial brains as “history.” But when we give in to enjoyment (be the good thief), we may literally step outside of history and commune with the past and future.

Although Žižek steers way clear of linking his (or Lacan’s) theoretical framework to mysticism or Gnosticism (which he dismisses as ‘New Age obscurantism’), his theory of symptoms very nearly corresponds to Dick’s theory of orthogonal (or fifth-dimensional) Time: A symptom is an eddy in the spacetime continuum, a vortex or whirlpool in which the patient’s enjoyment is trapped and cannot move forward until interpretation releases it. That interpretation, the enunciation of the meaning that gave rise to the symptom in the first place, is like the spear that pierced Christ’s side and that gave rise to Anfortas’s wound; it is the object that caused it and will heal it too, according to a kind of time-loop paradox. Thus the cure of the symptom (the best “salvation” that can be hoped for in psychoanalysis) is a substance, like light or enjoyment or Christ’s blood, that is outside of history’s temporal flow.

Symptoms, these enjoyment traps, are “caused by the future” in the sense that reordering the symbolic world to give them meaning (and hopefully dissolve them) actually transforms the past, un-does their traumatic cause, because the only place history is encoded or persists is in the ever-changing order of symbols and meanings. There is no “objective” history outside of the constantly shifting order of symbols, and there are real places where this order dissolves and breaks down. The only thing that is really permanent is enjoyment itself, which exists in these singularities of the Real, outside the bounds of the known.

If we take that idea literally and seriously, it potentially offers a rich theory not only of mysticism but also of synchronicity, paranormal phenomena, and the relationship between mind and causality. I would suggest that the enjoyment Žižek’s sublime objects and Dick’s common constituents are made of is precisely the “nonlocal” field or substance sought by theorists of ESP, for example, as well as countless writers lately seeking to replace modern reductive materialism with some better theory that privileges Mind or consciousness.

If Time and enjoyment are interconvertible, then enjoyment, not the vague catch-all “consciousness,” may be real ground or substrate of being, and the missing link in current attempts to reconcile mind and material causality. Or, enjoyment might be understood as a kind of purified, rarified consciousness—the quintessence of consciousness—which would correspond to countless mystics’ descriptions of the ocean of nondual bliss-awareness awaiting us in deep meditative states. (I’ll return to this subject in future posts.)

Incredible – no, MOST credible. A fellow “thinker” along the same “eternal now” vision as is so natural for me. I paused my reading of this article about 10% through to write these praises, “knowing” what is “coming” based on what I’ve seen. It is all in my mind now, just not yet all manifested, from “my” point of view, until light reveals the rest of your words. It is all in the “now moment”, just causally being played out on my creepy little mind machine – there, just not “yet” consciously registered, from “my” point of view. You speak my mind before my thoughts have manifested at the surface.

I have played photon for many years. Impossible it is for me to avoid speaking in terms of time, yet realizing all along there is no “time”, only Now. It is all simultaneous – NOW. So much more to say, none of which I need to say, nor can I reduce it to words. You already know. The only thing I can add now, “Thank the Divine One” for your putting this truth into words, in what little way it can be hinted at in words, the One with which we are One. “We” are not two – we are one. You speak for me because you ARE me, and I you dancing on different places, simultaneously.

Now, back to the incremental revelation of that which already is, as I read, think, realize, and say “Yes, I agree with that”, meaning, “I remember that”.