Prophecies, Time Loops, and Bubble Realities: La Jetée and The Sacrifice

If precognition is real, then we have to take account of the range of sci-fi effects it would produce, effects that go beyond the strictly ‘prophetic.’ Because we fail to see how our consciousness is receptive to the future and how our actions contribute to, and only in a minority of cases confirm, that future, we fail to recognize the range of effects that Chaos Theory would predict should occur.

The most common kind of effect would be negation of precognitive information because our freely willed actions cancelled the validity of that information and turned it into noise. In such cases, we would never even know the precognitive information was information, so it can be ignored. This first possibility I already dealt with in my “Psi of Regret” post a few months ago: There are all kinds of reasons why, in a universe full of conscious, freely willed actors, precognition would tend to negate itself.

The downside of taking responsibility as a freely willed being in the universe is being unable to ever say for certain whether prophecies are genuine.

Less commonly, though, feedback effects would result in an intensified significance to coincidental events, or what people often call a “synchronicity”; our failure to believe in psi or to acknowledge our own (unconscious) role in this feedback loop produces the illusion that some meta-symbols have a cosmically ordering power in these events (i.e., Jung’s concept of archetypes). This more interesting and rarer fork in the bifurcation predicted by Chaos Theory, the intensifed phenomenon of the synchronicity as a kind of ‘attractor,’ is interestingly explored in the film Don’t Look Now, the subject of my last post: Misrecognizing a precognitive vision as present reality produces a synchronistic perfect storm that ends up claiming the life of a hardened materialist skeptic.

In Don’t Look Now, the events set in motion by the protagonist’s failure to include the knower in the known are precisely what enable the future to control his fate: Our fate is only predetermined when we do not recognize our own free will, and fail to see that our awareness encompasses our life and death—that it exists to some degree outside of time and can see into the future and the past.

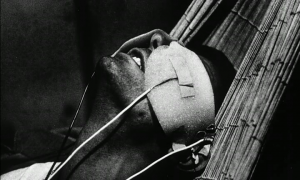

Chris Marker’s wonderful 1963 short film La Jetée, composed almost entirely of still images, is another beautiful expression of this idea.

Misrecognition and Time Loops

In La Jetée, desperate subterranean survivors of a nuclear holocaust in post-nuclear-war Paris have developed the technology of time travel—in the form of a psychoactive drug—as a means to summon aid and resources from the past and future. To test it out, they select a war prisoner as a guinea pig, based on his strong fixation on an image from his childhood: a beautiful woman watching a man shot to death on the observation platform (“jetty”) at Orly Airport. Holding a powerful image in mind is necessary to stabilize the time traveler’s presence in the destination time.

After initial abortive attempts, the test subject is able to maintain himself in the past, and finds the woman of his childhood image. They wander together around prewar Paris, visiting museums and parks, falling in love—at one point, standing before a cut tree trunk with dates assigned to the different rings, he points to a spot in the air outside the tree’s circumference and says “This is where I come from.” But he is not allowed to stay in this idyllic past; his jailers retrieve him and send him to the future to retrieve needed technology to help the human race survive—the mission he was always intended for. Having accomplished this, his jailers return him to his cell, his role in their plans now complete. However, he is mentally contacted by beings from the future who are able to grant his wish to return to his lover in prewar Paris. When he goes back in time—he hopes permanently—he sees her at Orly jetty and runs toward her, but is shot by one of his prison guards, who has followed him back in time. He finally realizes that it was his own death he had seen as a child.

After initial abortive attempts, the test subject is able to maintain himself in the past, and finds the woman of his childhood image. They wander together around prewar Paris, visiting museums and parks, falling in love—at one point, standing before a cut tree trunk with dates assigned to the different rings, he points to a spot in the air outside the tree’s circumference and says “This is where I come from.” But he is not allowed to stay in this idyllic past; his jailers retrieve him and send him to the future to retrieve needed technology to help the human race survive—the mission he was always intended for. Having accomplished this, his jailers return him to his cell, his role in their plans now complete. However, he is mentally contacted by beings from the future who are able to grant his wish to return to his lover in prewar Paris. When he goes back in time—he hopes permanently—he sees her at Orly jetty and runs toward her, but is shot by one of his prison guards, who has followed him back in time. He finally realizes that it was his own death he had seen as a child.

The time loop is broken through the final “interpretation” or moment of insight: ‘It was me all along enjoying this dark, perplexing story (the story of my life).’

The narrator says, as the man from the future steps out onto Orly Jetty the last time, that “confusedly, he expected to see a small boy, his younger self.” Yet there is no such boy there to witness this event, leaving us with the conclusion that his “memory from childhood” was really a precognitive dream or vision of his own death—in other words, exactly the fatal misrecognition that destroys John Baxter in Don’t Look Now. Thus La Jetee, which was the original inspiration for Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys, beautifully illustrates the Lacanian notion of a symptom as a kind of time-loop sustained by misrecognition of trauma, failure to include the knower in the known. The loop is broken through the final “interpretation” or moment of insight: ‘It was me all along enjoying this dark, perplexing story (the story of my life).’

The sustaining ‘enjoyment’ in this fable is explicit in the way that time travel is conflated with a drug experience—a syringe calls to mind a drug addiction, perhaps the purest form of pleasurable-painful-destructive jouissance. When the man is returned to his cell after his “trial runs” in the past, it is as an addict taken away from the source of his enjoyment. We could perhaps also see his need as the thing that opens a door to communication with the future beings who are able to grant his wish for a final, fatal return to the past.

The sustaining ‘enjoyment’ in this fable is explicit in the way that time travel is conflated with a drug experience—a syringe calls to mind a drug addiction, perhaps the purest form of pleasurable-painful-destructive jouissance. When the man is returned to his cell after his “trial runs” in the past, it is as an addict taken away from the source of his enjoyment. We could perhaps also see his need as the thing that opens a door to communication with the future beings who are able to grant his wish for a final, fatal return to the past.

Every film is a Rashomon, though, and there are other ways of interpreting what “really happens” in La Jetée. The entire story of the film could be a fantasy produced in this war prisoner’s dying moments, for example, as in Ambrose Bierce’s “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”: A confederate sympathizer and saboteur is being executed by hanging, from a bridge during the Civil War; the rope breaks, allowing him to escape into the water and flee through the forest to his plantation and the arms of his waiting wife. As he approaches her, he feels the noose tighten around his neck and he “awakens” to the reality of his death.

But there is also a further possibility, that the real subject of the film is the woman, and that the whole story is her lonely fantasy or dream of a love affair with a man with no past, projected onto the fantasized gaze of a young boy who could be their fantasy child. The fact that the only actual motion in the film is a few seconds of the woman opening her eyes in bed hints at this possibility.

But there is also a further possibility, that the real subject of the film is the woman, and that the whole story is her lonely fantasy or dream of a love affair with a man with no past, projected onto the fantasized gaze of a young boy who could be their fantasy child. The fact that the only actual motion in the film is a few seconds of the woman opening her eyes in bed hints at this possibility.

2 x Double = Toil + Trouble

What happens in a sci-fi universe where time loops and precognition are real and we do include the knower in the known? Here’s where we are caught in a paradox. Negative precognitions or premonitions (John Baxter seeing his own funeral procession, the man from the future seeing his own death) could only be verified if we do not act upon them to change our destiny—and thus, presumably, would only be apparent after the fact, if we consciously fail to recognize their true nature.

On first glance, Don’t Look Now and La Jetée might thus seem like the opposite of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, where a prophecy destroys because it is obeyed to the letter rather than skeptically questioned or mistaken as involving someone else. But really the effect of willed disbelief or misrecognition is the same as the effect of insecure belief—hastening to fulfill the prophecy lest it not come true, as it were, “on its own.” It is MacBeth’s anxious efforts to fulfill the prophecy that catch him in the witches’ fatal logic and destroy him just as surely as rigid disbelief in the paranormal destroys John Baxter or misrecognition of his ’symptom’ draws the protagonist of La Jetée to his doom.

On first glance, Don’t Look Now and La Jetée might thus seem like the opposite of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, where a prophecy destroys because it is obeyed to the letter rather than skeptically questioned or mistaken as involving someone else. But really the effect of willed disbelief or misrecognition is the same as the effect of insecure belief—hastening to fulfill the prophecy lest it not come true, as it were, “on its own.” It is MacBeth’s anxious efforts to fulfill the prophecy that catch him in the witches’ fatal logic and destroy him just as surely as rigid disbelief in the paranormal destroys John Baxter or misrecognition of his ’symptom’ draws the protagonist of La Jetée to his doom.

True freedom from prophecy seemingly is obtained by believing in the prophesied possibility as a virtual outcome but knowing we have some say in the matter. But the downside of taking responsibility as a freely willed being in the universe is being unable to ever say for certain whether prophecies (our own or those of seers we have faith in) are/were genuine. In a sense, the result is the sketch-like world described by Milan Kundera in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, in which nonrepetition—transience, Heraclitus’s inability to set foot twice in the same river—results in an “unbearably light” insubstantiality to things.

Yet, as I’ve argued before, this suspended belief in prophecy’s ‘hardness’ is the truly healthy stance. We must assume a skeptical distance both from reductive linear materialist causality (“there are no messages from the future”) and from “synchromystic” determinism in which the Big Other somehow perfectly knows us and controls our fate.

What Happens in a Sci-Fi Universe Stays in the Sci-Fi Universe

This middle attitude produces a third, purely theoretically but exotic possibility: that precognitive information will at times produce alternative ‘bubble histories’ that are isolated from the stream of causality through the conscious willed action of the recipient of future information. In a sense, this non-possibility is a theoretical ghost that hovers over all of reality when we acknowledge the existence of information reaching into and affecting the past in a universe that also includes free will.

How could we ever know whether a person’s psychotic or obsessive behavior is not, really, a sacrifice being made to forestall some personal or cosmic tragedy by isolating it in a bubble universe? Are some madmen really martyrs?

A few excellent films have explored this idea in different, creative ways. Donnie Darko is the most obvious: At the end of the film, we realize that the disastrous events leading up to the protagonist’s death are a bubble reality isolated from the time stream by his heroic sacrifice, creating what in theoretical physics has been called a “closed timelike curve.” In many ways, the film is a retelling or permutation of It’s a Wonderful Life, except in that case the negative/feared historical outcome is neutralized/negated by the protagonist not allowing himself to die.

But my favorite exploration of the possibility of a heroic sacrifice saving the protagonist’s universe is Andrei Tarkovsky’s beautiful final film, The Sacrifice. Despite appearances of being a slow (at times, paint-dryingly slow) Bergman-esque chamber drama about an aging artist’s birthday gathering, it is really a science fiction film, and one that all true Forteans owe it to themselves to see.

Alexander, a former actor now enjoying his retirement with his wife and young son at a beautiful country house in rural Sweden, meets the local postman, Otto, who turns out to be a “collector” of uncanny paranormal occurrences—essentially, a Swedish Charles Fort. Beyond merely collecting and cataloging such incidents, Otto actually goes to great lengths (he says) to verify them.

Alexander, a former actor now enjoying his retirement with his wife and young son at a beautiful country house in rural Sweden, meets the local postman, Otto, who turns out to be a “collector” of uncanny paranormal occurrences—essentially, a Swedish Charles Fort. Beyond merely collecting and cataloging such incidents, Otto actually goes to great lengths (he says) to verify them.

Otto visits Alexander’s country house to give him a rather excessive birthday gift—a precious antique map (he explains that “all gifts require a sacrifice”)—and while he is there, a TV alert somberly announces that a nuclear war has broken out; citizens are urged to stay calm, but the mood is gloomy, and Alexander’s family are able to hear the rockets flying overhead, launched from nearby missile silos. In solitary terror and desperation, Alex prays: He will give up speech and even give up his family and his house to end the war.

Otto then privately confides in him that there is one chance to save everything—save the world—and that is that Alexander must go to the home of his own servant, Maria—who is actually (Otto says) a witch—and sleep with her. Alex hesitates, but then gets on his bicycle, rides to her house, and fulfills this act. He returns home, falls asleep, and then wakes to find that there is no nuclear war—things are normal, no one is panicked. Was it all a dream? We don’t know. But keeping his promise, Alex falls silent, methodically sets fire to his home while his family is out for a walk, and finally, running around the burning house like an ecstatic (and silent) madman, is taken off by an ambulance.

Otto then privately confides in him that there is one chance to save everything—save the world—and that is that Alexander must go to the home of his own servant, Maria—who is actually (Otto says) a witch—and sleep with her. Alex hesitates, but then gets on his bicycle, rides to her house, and fulfills this act. He returns home, falls asleep, and then wakes to find that there is no nuclear war—things are normal, no one is panicked. Was it all a dream? We don’t know. But keeping his promise, Alex falls silent, methodically sets fire to his home while his family is out for a walk, and finally, running around the burning house like an ecstatic (and silent) madman, is taken off by an ambulance.

Through his sacrificial act, we are led to believe, Alex has not “ended the war” but rather prevented it from ever happening. If only he remembers it, we can ask if he really is a madman, or if he really changed the future through a strange ritual recommended by his Fortean friend. There is no way to know what is “really real,” whether any of it was a dream, and whether his sacrifice (giving up speech and his house and family) is actually a significant history-altering pact with the silent universe … or whether it is just a psychotic break.

Lacan noted that neurotic rituals are often undertaken to cover over an emptiness, the lack in (or nonexistence of) the Big Other. But if time is multidimensional and looping, and if synchronicities emerge from misrecognized precognition or from double causation (Vallee’s phrase), it raises the possibility of encapsulated bubble histories, like growths or polyps sprouted by the stream of time and severed through some “mad” (or merely neurotic) act—some sacrifice—which may even save the world.

Lacan noted that neurotic rituals are often undertaken to cover over an emptiness, the lack in (or nonexistence of) the Big Other. But if time is multidimensional and looping, and if synchronicities emerge from misrecognized precognition or from double causation (Vallee’s phrase), it raises the possibility of encapsulated bubble histories, like growths or polyps sprouted by the stream of time and severed through some “mad” (or merely neurotic) act—some sacrifice—which may even save the world.

So The Sacrifice raises a disturbing question not only about the shape of time but also about mental illness: How could we ever know whether a person’s psychotic or obsessive behavior is not, really, a sacrifice being made to forestall some personal or cosmic tragedy by isolating it, encapsulating it, in a kind of self-cancelling bubble universe where it can no longer harm anyone? Are some madmen really martyrs who have sacrificed their sanity to save the world?

Eric,

Your recent posts act in a catalytic manner on many internal thoughts and ideas.

I feel glad that I discovered your site, via the valuable comments of my friend and remarkable explorer of the Unknown, Thanassis Vembos.

Greetings from Greece