Destination Pong (Precognition and the Quantum Brain)

For decades, parapsychologists have been looking to quantum physics as the cavalry that might rescue them from their scientific exile by providing a theoretical justification for psi phenomena. Particles in quantum systems can teleport, become entangled so they behave in unison (no matter how far apart they are), and exist in multiple states simultaneously; also their interactions are identical going backward as going forward. Naturally, the fact that such interactions verifiably exist in nature has held out hope that quantum principles might one day explain stuff like telepathy, remote viewing, and precognition, as well as psychokinetic effects.

If the brain turns out to have quantum computing properties, this could even open the door to a realistic physical explanation for the most causally outrageous form of psi, precognition.

The problem, and the reason skeptical critics have been justified in dismissing any link between claimed psi phenomena and quantum physics, is that Alice-in-Wonderland quantum principles describe the very microscopic world of particles, not the world of people. They have mainly been known to “scale up” only in very special conditions, when very small groups of entangled particles can be strictly isolated from interaction with their environment and thus protected from what is known as “decoherence”: Entanglement washes out very quickly once particles interact with other particles—making it hard to see how it could really be used to explain things like telepathy or remote viewing. In a laboratory, sustaining quantum-coherent systems has proved difficult to achieve other than at very low temperatures (approaching absolute zero) and generally only for very small (still microscopic) objects, for very brief lengths of time.

Over the past two decades, however, a growing number of findings in biology are revising this picture: Quantum processes do occur at a macro scale, and even in warm, wet, and messy biological systems; they are even essential to life as we know it. Quantum tunneling—the ability of a particle to pass through a barrier by becoming a wave, taking multiple paths simultaneously—is essential to photosynthesis, for example, leading the discoverer of this phenomenon (Graham Fleming) to suggest that plants are, in some sense, quantum computers. Quantum tunneling is also essential to the catalytic action of enzymes, and quantum entanglement may be involved in magnetoreception (navigation by magnetic fields), for instance in birds.

The suspicion that the brain may also have quantum properties and that this may provide some kind of explanation for consciousness goes back three decades, to Roger Penrose’s idea that microtubules in neurons may be sites of quantum effects enabling entanglement both within and between brain cells. Penrose teamed with anesthesiologist Stuart Hameroff to formulate the controversial “orchestrated objective-reduction” (Orch-OR) theory, positing that neurons themselves act as quantum computers and are the real locus of computation in the brain. Other researchers have focused on narrow ion channels in neuronal walls, which control the movement of neurotransmitters into the cell and thus their voltage, as possible sites of quantum effects. In their recent book on the emerging field of quantum biology, Life on the Edge, Johnjoe McFadden and Jim Al-Khalili propose that the brain’s electromagnetic field may couple to quantum-coherent (entangled) ions moving through these channels and synchronize them, enabling the “binding” of multiple cortical processes, and that consciousness may be tantamount to this system-wide orchestration of neural activity.

There’s no proof for any of this as yet, but clearly the race is on to discover quantum processes in the brain, and thus we are at the dawn of a new era of quantum neuroscience to go along with quantum biology. It certainly makes sense that if any biological system capitalizes on quantum principles and scales them up—including their spookier and more baffling properties—it might be the brain, famously the most complex structure known to exist in the universe.

Like many people, I’m skeptical of the effort to explain consciousness per se as an effect of brain processes, even quantum brain processes. Invoking quantum physics doesn’t make the endeavor any less philosophically unsound (quantum or not, the brain will always be demonstrably “within consciousness” no matter how much we assert the reverse). Mainly, though, I think it is a bit of a red herring and represents a semantic confusion, since the real operative term that we mystics and mysterians ought to be interested in is something more like “enjoyment,” whose properties are very different from what we ordinarily think of when we hear the word “consciousness.” (Some of the functions associated with consciousness—including any sense of self and memory—I feel surely are mediated by the brain.) Nevertheless, I am cheered by the exercise of searching for consciousness (whatever it means) in the quantum-friendly microstructures of neurons because I think the unintended byproduct of this confused effort is likely to be precisely the physical explanation for psi that parapsychology has always dreamed of but could never specify.

Like many people, I’m skeptical of the effort to explain consciousness per se as an effect of brain processes, even quantum brain processes. Invoking quantum physics doesn’t make the endeavor any less philosophically unsound (quantum or not, the brain will always be demonstrably “within consciousness” no matter how much we assert the reverse). Mainly, though, I think it is a bit of a red herring and represents a semantic confusion, since the real operative term that we mystics and mysterians ought to be interested in is something more like “enjoyment,” whose properties are very different from what we ordinarily think of when we hear the word “consciousness.” (Some of the functions associated with consciousness—including any sense of self and memory—I feel surely are mediated by the brain.) Nevertheless, I am cheered by the exercise of searching for consciousness (whatever it means) in the quantum-friendly microstructures of neurons because I think the unintended byproduct of this confused effort is likely to be precisely the physical explanation for psi that parapsychology has always dreamed of but could never specify.

That is to say, even if consciousness is a basic mystery, I don’t think psi is, and I think we can do better than invoke vague ideas of “nonlocality” and the “holographic universe.” If the brain turns out either to be a quantum computer or, more realistically, to have quantum computing properties in tandem with its better-understood classical properties, this could even open the door eventually to a realistic—and most importantly, testable—physical explanation for the most causally outrageous form of psi, precognition.

Dropping the Bohm

In some recent articles, Jon Taylor has proposed a very interesting theory of precognition as memory of one’s future experiences, based on a “resonance” between similar brain states at different points in time. He bases this idea on David Bohm’s argument that similar spatial configurations are somehow naturally linked across space and time. The similarity of configurations of cortical firing at different time points could, Taylor proposes, enable such a resonance between different points in the brain’s timeline and thus produce precognitive effects. These would preferentially favor precognition of events closer rather than more distant in time, due to ongoing plasticity (creation of new synaptic connections) that gradually changes our neuronal connectivity. Limited telepathy is also potentially supported by Taylor’s model, although it would be less common given the relative dissimilarity of different people’s brains (the similarity of siblings and twins, between whom telepathic experiences are commonly reported, being the exception proving the rule). Taylor’s hypothesis resembles Rupert Sheldrake’s argument about “morphic resonance” as the basis of memory; precognition would be essentially a future-resonating mirror of memory’s resonance with past brain states.

Picture Jeff Bridges being digitized by the laser, as in Tron, but instead materializing ten years earlier inside an old Pong console.

I lean strongly to the view that psi is mostly, or possibly even only, precognition, given the difficulty of excluding this source of information even in studies of purported telepathy and remote viewing (and even spirit mediumship). Some form of feedback or confirmation has been present in most experimental and real-world demonstrations of these abilities, it seems, and ‘forensic’ examination of individual cases suggests that psychic subjects often are receiving information from “scenes of confirmation” in their own future even when they think they are getting it from other minds or distant points in space. It’s a suspicion that has hovered over ESP research from early on, and has led researcher Edwin May to argue that all psi is basically precognition. I also agree with Taylor that precognition is inextricably connected to associative memory processes (more on this in the next post).

But as a physical explanation for how this could work, I’m not very persuaded by the Bohmian resonance argument that similar spatial configurations somehow share a special affinity. This is what bugs me about Sheldrake’s arguments as well: The idea that forms “resonate” seems to require someone somewhere to decide what counts as a form in the first place, and how to measure a form’s similitude to another form. It’s a Platonic model, and as such I think it puts the cart of form before the horse of embodied human conscious or unconscious agency … for instance in the form of psi. (Jung’s theory of synchronicity suffers the same problem, as I argued in my anti-synchronicity diatribe this past spring.)

An interesting alternative avenue for thinking about how precognition of one’s own future experiences could occur comes from recent developments in quantum computing and research in the transmission of information via quantum teleportation. In 2010, Seth Lloyd and colleagues proposed that teleportation can be used to send information back in time, not just across space; they then tested this idea in 2011. Lloyd’s idea is monumental, because it has shown for the first time how a real kind of time travel can be achieved non-relativistically, without massively bending space as in a black hole or Kardashev III-style wormhole (for instance as depicted in the movie Interstellar). Lloyd’s method rests on parapsychologists’ favorite quantum concept, entanglement … but not in the usual way it is typically invoked to explain telepathy and remote viewing.

Entanglement of two particles causes one particle to affect the other instantaneously; they do not “communicate” in any way that must obey the speed of light. In 1993, Charles Bennett proposed that this could be used to teleport information across space. Say you have a pair of entangled particles A and B, separated by some distance; you can compare particle B to another, third particle C to determine their relative properties (destroying the properties of C in the process). Once this is done, you can relay the information about B and C’s relationship to someone at the distant location, who can measure A and, from the knowledge about how B and C related, infer or reconstruct information about C. It sounds like a convoluted Rube Goldberg contraption, but it is cool because it amounts to the destruction of information in one place and the replication or reconstitution of that information in another place—basically, a transporter beam.

If the vague transporter effects of Star Trek don’t help you visualize this, picture video-gamer “Flynn” (Jeff Bridges) accidentally digitizing himself with a laser and being beamed into the world of Tron—that’s exactly how it works. This principle has since been demonstrated experimentally many times, over distances of as much as 89 miles (I believe the current record), using lasers to send one of a pair of entangled photons through open air.

If the vague transporter effects of Star Trek don’t help you visualize this, picture video-gamer “Flynn” (Jeff Bridges) accidentally digitizing himself with a laser and being beamed into the world of Tron—that’s exactly how it works. This principle has since been demonstrated experimentally many times, over distances of as much as 89 miles (I believe the current record), using lasers to send one of a pair of entangled photons through open air.

What Lloyd showed was that this setup can be modified to send information back in time instead of (or as well as) through space, if one of the two entangled particles is allowed to become fully entangled with that third particle C, breaking its entanglement to the first. As before, as long as particle A and B are entangled, information associated with them is shared; if particle B then an hour later becomes entangled with particle C, the original entanglement between B and A is broken, and information originally associated with the new particle C becomes lost by C but associated with the other “divorced” particle A in the original pair, and in the past—effectively, that “associated” information travels back in time. If I understand this correctly (and I invite more quantum-savvy readers to correct me here), you’d find that that “lost” information from C already was associated with A—you just didn’t notice it or have any way of interpreting it until you performed the operation of entangling B with C, within a setup where the outcome was pre-determined through a process known as “post-selection”—more on that below. (A good, clear explanation of Lloyd’s idea can be found here.)

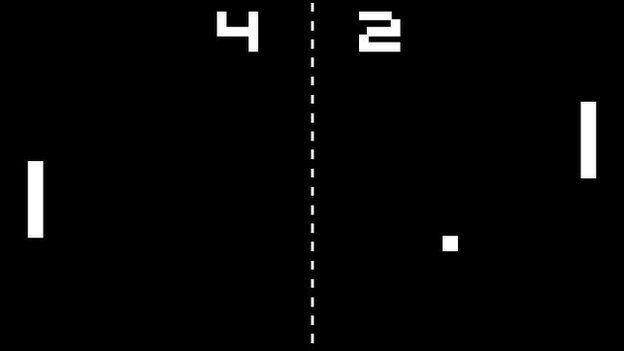

Lloyd considers this a way that information and potentially even matter could be teleported into the past. For this, you could perhaps picture Jeff Bridges being digitized by the laser, same as before, but this time materializing ten years earlier inside an old Pong console. (We’d later come to find he’d become ruler of a dull virtual table tennis scenario, and gone mad from the boredom.)

Lloyd considers this a way that information and potentially even matter could be teleported into the past. For this, you could perhaps picture Jeff Bridges being digitized by the laser, same as before, but this time materializing ten years earlier inside an old Pong console. (We’d later come to find he’d become ruler of a dull virtual table tennis scenario, and gone mad from the boredom.)

I think the informational possibilities of this teleportation method are even more exciting than the possibility of beaming physical objects or people into the past, given the concurrent effort to understand the quantum-computer-like properties of the brain. If the brain or its constituent cells can scale up quantum effects by creating systems of entangled particles that are kept coherent over spans of time (that is, protected from jostling with other particles and used to perform calculations, even just over milliseconds or seconds), then information could be sent into the past and extracted by observation/measurement. Precognition, in other words.

The Death of Randomness

Lloyd’s theory takes advantage of the principle that, at a quantum level, information is never lost, but only traded back and forth among particles as a result of their entanglements; future entanglements thus can influence the past.

This is where, to understand Lloyd’s breakthrough, you need to appreciate a possibly even bigger deal in quantum science, the slow death of the old doctrine that particles behave randomly—the “God playing dice” idea that so offended Einstein. Turns out, a lot of physicists think Einstein was probably right. According to the “two-state vector formalism,” the apparent random behavior of particles is only an effect of our inability to take into account the influences of their future measurements (i.e., interactions with other particles). In other words, particles’ future histories determine how they behave in the present as much as their past histories. “Randomness” is really “noise” from which no signal can be extracted, because we don’t know the properties of the particles that a given measured particle will be associated with in its future.

This is where, to understand Lloyd’s breakthrough, you need to appreciate a possibly even bigger deal in quantum science, the slow death of the old doctrine that particles behave randomly—the “God playing dice” idea that so offended Einstein. Turns out, a lot of physicists think Einstein was probably right. According to the “two-state vector formalism,” the apparent random behavior of particles is only an effect of our inability to take into account the influences of their future measurements (i.e., interactions with other particles). In other words, particles’ future histories determine how they behave in the present as much as their past histories. “Randomness” is really “noise” from which no signal can be extracted, because we don’t know the properties of the particles that a given measured particle will be associated with in its future.

The future is right here, right now, a whole backwards-facing tidal wave of causality that is just as important for dictating nature’s unfolding as its billiard-ball past is; it is just far more obscure.

The special conditions stipulated in Lloyd’s scenario—that is, a quantum computer in which sequestered entangled particles can be carefully re-entangled while subjected to the constraint of post-selection—is the exception to this rule. In such a circumstance, since the endpoint or output of the computation is restricted to a particular result, the meaning of particles’ prior behavior—that is, the information associated with them that was the “result” of a future entanglement—can be extracted in the past, and thus the “future cause” known in advance.

Post-selection means that outcomes must fall within the range of possibility to be allowed; this is what prevents Lloyd’s quantum computer/teleportation scenario from committing the paradoxes associated with time-travel, such as the “grandfather paradox.” The only states that can emerge as outcomes are ones that do not prevent that outcome from occurring, yet a range of paths are permitted to get to that outcome. (One “spooky” feature of particles is their ability to take multiple paths simultaneously to a destination in space, known as a quantum walk; post-selection seems to be sort of a temporal version of this idea, although I have not seen it explained that way.) Some accounts of Lloyd’s theory of time travel even suggest that outrageous twists of fate would arise in some cases to prevent future-cancelling outcomes.

Although post-selection is used in a quantum computing context as a kind of programming choice, Its implications for how we think about reality itself are profound. In a sense, post-selection is just a special application of the larger principle that we live in a possible universe. When applied to the problem of precognition, all post-selection means is that informational time travel must produce a possible outcome and not a contradiction. But we are looking at it wrong in thinking that outrageous measures would be taken by the universe as prophylaxis against paradox; the point is, the information would not have traveled in time in the first place if it caused a contradiction, not because some deus ex machina intervened, but because it wouldn’t be information, just noise whose origin couldn’t be pinpointed.

We are really forced to resort to circular reasoning to describe reality: Things that happened happened, things that didn’t didn’t. The only way to make this seem non-tautological is to parse it out and walk around the loop on foot, seeing only part of the whole at a time. Logic (and perhaps the limits of human understanding, or at least left-hemisphere understanding) requires we we play this game of pretend, which is essentially what mechanistic causality always was. But the basic structure of reality is a “cell” formed by backward-in-time data informing action that either leads to some event which generates the data or is noise, in which case the information we suspected came from a future event didn’t actually emanate from that event or was misinterpreted. It is only precognition if and to the extent that it comes true. This can give you a headache to think about, but it really points to the insufficiency of causality: It’s a social model used to assign responsibility and “blame” for events, but zoom out too far and its fictitiousness becomes apparent.

If all this sounds like an argument for total determinism (or at least, for precognition as precognition of what must occur), it is not. We are really no closer to settling the determinism vs. free will question, because “particle randomness” was never the savior of free will anyway, even when back when we thought God played dice. It seems to me that an essential characteristic of precognition is its non-total, imperfect nature: Psi information is only information to the extent that it can be matched against reality—that is, confirmed—and this probably falls in a gradation or range (or “smear”). There’s no absolutely correct or total psi information because then there wouldn’t be an “outside” to the information, and no way of knowing it even existed; on the other extreme, totally wrong information wouldn’t be information, only noise, and no one would have acted upon it.

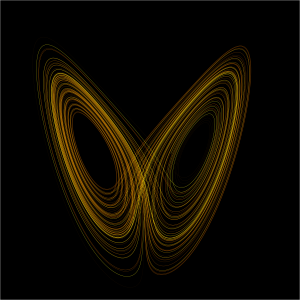

This is what I meant several months ago (in my attack on Jung) by the strange attractor; the strange attractor is between psi information and noise. It is noise to the extent that our knowledge (potential or suspected psi) does not match the future. Noise is one wing of the butterfly. The other wing is when our knowledge (potential psi) does match. In this case, we call it psi. But the point is, there is always a backflow or backwash of proto-information traveling into the past; only within a coherent structure like a quantum computer may it be usable and actionable as information per se, yet precisely the energy invested in heeding the information or using it to orient toward the right answer in the future deviates the right answer, altering the status of the information the psychic received. Frank Herbert keyed in on this when describing Paul Muad’Dib’s precognitive abilities in Dune:

This is what I meant several months ago (in my attack on Jung) by the strange attractor; the strange attractor is between psi information and noise. It is noise to the extent that our knowledge (potential or suspected psi) does not match the future. Noise is one wing of the butterfly. The other wing is when our knowledge (potential psi) does match. In this case, we call it psi. But the point is, there is always a backflow or backwash of proto-information traveling into the past; only within a coherent structure like a quantum computer may it be usable and actionable as information per se, yet precisely the energy invested in heeding the information or using it to orient toward the right answer in the future deviates the right answer, altering the status of the information the psychic received. Frank Herbert keyed in on this when describing Paul Muad’Dib’s precognitive abilities in Dune:

The prescience, he realized, was an illumination that incorporated the limits of what it revealed—at once a source of accuracy and meaningful error. A kind of Heisenberg indeterminacy intervened: the expenditure of energy that revealed what he saw, changed what he saw.

Libet’s Golem

Psi, as Rhine Center parapsychologist James Carpenter argues, is basic to our thinking and functioning, not some superficial add-on “ability” (or as some would have it, “superpower”). Precognition may be a basic function whereby the brain sends information into its own past—or more likely, billions of miniature quantum computers within the brain are sending information into their pasts. Hypothetically, a statistical perturbation in particle behavior (for instance, in those microtubules or the ion channels of synapses) would produce a perturbation in the system at a macro level that stimulates certain associations and not others, in a way that can be minimally trusted by the (classical) associative system as carrying usable information. That minimal trust in one’s future neural connectivity is a function of repetition and habit—we must establish habits or rituals of confirmation (these may be totally unconscious), which build up the psi-system’s trust in future information, which our psi guidance system can then home in on. In other words, habit and expectation create a kind of minimal “post-selection.” (On a conscious level, ritual can serve this purpose in any project of working with psi, such as in precognitive dreamwork.)

Our conscious intent could be unknowingly pulling our meat puppet’s strings from a position dislocated slightly into the future, where the results of the action are already more or less known.

If this is the case, it could be that infant cognitive development amounts to learning to sort out psi signal from noise, and that this involves building up the basic self-trust of “me in a half second,” “me in a few seconds,” and so on that enables precognitive information to be reliably used for basic motor tasks. During our development, we gradually home in on the minimally useful short-term psi signal that enables planning but doesn’t screw things up for us socially, again by building up that structure of self-knowledge and trust in our associative and cognitive habits. Meanwhile, social learning imposes strict limits on overt, conscious expression of precognition, for a wide range of cultural reasons.

Rubbing my temples, I foretell that a future neuroscience of psi will find that something like this interaction between quantum computation involving “closed timelike curves” within neurons and system- or circuit-level associative networks will turn out to be the basic function of the cortex, although it will also depend crucially on subcortical reward regions, as I suggested in a previous post, as these are crucial in reward and the development of habits.

I also wonder whether our behavior might turn out to have relatively little to do with using information from memory to fashion mental representations and action plans—that that whole story (i.e., cognition as occurring “in the past,” prior to action) may be an inadequate or incomplete picture that needs psi to supplement it. Effective (i.e., skilled, Zen-like) motor action might occur from a place after action, a place that already knows the outcome.

I also wonder whether our behavior might turn out to have relatively little to do with using information from memory to fashion mental representations and action plans—that that whole story (i.e., cognition as occurring “in the past,” prior to action) may be an inadequate or incomplete picture that needs psi to supplement it. Effective (i.e., skilled, Zen-like) motor action might occur from a place after action, a place that already knows the outcome.

I think of this possibility as “Libet’s golem,” because it would be like an ironic, science-fictional perversion of Benjamin Libet’s troubling/awesome discovery that conscious intent follows motor actions by a fifth of a second. It could be this is true because our conscious intent is unknowingly pulling our meat puppet’s strings from a position dislocated slightly (e.g., a fifth of a second) into the future, where the results of the action are already more or less known. This would be especially the case when engaged in a skilled activity, and would account for the slightly dissociated feeling that accompanies intuition and creative or athletic flow states. (Gives a whole new meaning to “be here now.”)

Quantum Promiscuity

This all remains highly speculative … obviously. But regardless of whether Lloyd’s setup or something like it characterizes computing operations in the brain, the significance of the new developments in quantum theory for understanding time and causality itself cannot be overstated, because they provide the necessary context within which precognition will eventually be rendered palatable to the scientific mainstream.

Particles behave like little rock stars or college students in a sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll haze, sleeping with a new partner or two each night, swapping clothes, prescriptions, playlists, and cold sores.

For at least a century, scientists have sought to understand the emergence of order within a universe governed by the entropy, our best proxy for time’s arrow, and it has never quite seemed to add up. Again and again, keen thinkers have resorted to invoking some sort of as-yet-unidentified form of retrocausality. In 1919, Paul Kammerer argued for “seriality” as a kind of determination from the future, a convergence on future order. His theory was highly influential on Carl Jung’s theory of synchronicity, which tried to replace causality with meaning as the glue connecting events. Then, within the field of general systems theory, some theorists proposed some sort of countervailing force to entropy that would make sense of the emergence of complex and intricate forms despite the supposedly inexorable tendency toward chaos. Various theories under the umbrella of what Luigi Fantappie called “syntropy,” have proposed that systems gravitate toward future attractors (I highly recommend DiCorpo and Vannini’s recent book Syntropy on this).

The reconsideration of randomness as the omnipresent but impossibly noisy effect of the future on the present comes alongside a major realization about what causes entropy in the first place. The second law of thermodynamics had always been understood and explained as a statistical product of randomness—almost as if math, the law of large numbers, could magically exert a causal effect on a system. Random behavior of particles leads any ordered system to move inexorably toward disorder, an averaging out of differences and thus a loss of information, but randomness does not by itself explain how heat dissipates through a medium and why order tends toward chaos. This is something that Arthur Koestler intuited in his excellent 1972 book on ESP, The Roots of Coincidence: The law of large numbers cannot explain anything—it is a statistical tendency, but math alone is not determinative; statistics don’t cause things to average out. Resorting to tricks of statistics has really been one of science’s fig leafs, when it comes to some of the most basic phenomena in nature at a macro scale.

The reason for entropy, it now turns out—once again, because of Seth Lloyd’s work—is our old friend entanglement: Particles, when they come into contact with each other, take on the properties of their new mates, and simultaneously lose their previous, more distinctive properties. I like to think of this as quantum promiscuity—particles behave like little rock stars or college students in a sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll haze, sleeping with a new partner or two each night, swapping clothes, prescriptions, playlists, and cold sores. These attributes diffuse through a community of interacting individuals, resulting in their becoming more and more similar. By the end of their freshman year, all college students are alike—the same clothes, diseases, musical tastes, etc. Same with particles, given enough time. Entropy is just the promiscuity of particles tending to share each others’ attributes.

Entropy, in other words, is not a loss of information but a sharing and homogenizing of information in the present, sending more distinct information into the past; it is the increasingly complicated nature of particles’ entanglements that produces the “averaging out” behavior seen in thermodynamic systems, making the information purely virtual (or noise). “The arrow of time is an arrow of increasing correlations,” Lloyd says.

Entropy, in other words, is not a loss of information but a sharing and homogenizing of information in the present, sending more distinct information into the past; it is the increasingly complicated nature of particles’ entanglements that produces the “averaging out” behavior seen in thermodynamic systems, making the information purely virtual (or noise). “The arrow of time is an arrow of increasing correlations,” Lloyd says.

So another way of looking at it is this: Lloyd’s model of time-traveling information is an idealized model of what all particles are doing all the time, but in such a haphazard, rapid, out-of-control way that no meaningful information can be extracted from the way they behave when measured, because those future entanglements are unknown to us and there is no known-in-advance endpoint to work back from. Randomness is an illusion caused by particles’ unrestrained future promiscuity and the open-endedness of future time.

The retrocausal effects of quantum entanglement provide an alternative, and most importantly empirically supported mechanism to theories like syntropy and seriality, as well as a more coherent and specific answer to vague “resonance” theories a la Sheldrake and Bohm. Astrobiologist Paul Davies has even argued that this influence of the future behavior of particles, and specifically the principle of post-selection, help explain the arising of life in the universe.

The take-home is this: The future is exerting an omnipresent influence on us, at the most intimate level of the matter and energy constituting us and our world. It is right here, right now, a whole backwards-facing tidal wave of causality that is just as important for dictating nature’s unfolding as its billiard-ball past is; it is just far more obscure. And nature does allow—and Seth Lloyd proved it—for special situations in which little pieces of that massive backwards wave of influence can be used to inform us of events still to come. Since Lloyd’s system requires “perfect” replication of information in the past, on the model of a transporter beam or an error-free computer circuit, the ability to fix the end parameters must be absolute. But human precognition need not be total and perfect, any more than any sensory information is total and perfect. It just needs to be “good enough for government work,” as they say.

In other words, it’s okay if any given Jeff Bridges isn’t replicated perfectly within his boring Pong game, but looks odd or has three arms or two heads. With billions of cells performing similar precognitive calculations, the brain could arrive at an adequate approximation, a “majority report” that is good enough to guide its behavior.

I especially like this new definition of entropy and its being the noisy background for the intuitive search-beams of skilled behavior. This is really the void that contains everything.

The point with information is that it is only information for an observer. To collapse information out of the void there have to be at least observational capacities. Or to put it another way, there has to be some kind of specific intent to frame the lens through which information from the void can be singled out. On the neural level this could temporarily be established by the neurobiological form of an emerging action.

I’m glad that you are doing the quantum-stuff. It’s really fascinating but totally not my cup of coffee.