Fool Me Once, Shame on You, Fool Me Twice, Shame on Me (Blade Runner and Mulholland Drive)

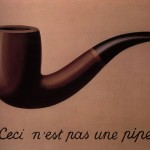

When Magritte painted a picture of a pipe with the words Ceci n’est pas une pipe (“This is not a pipe”) underneath it, he was trying to get the viewer to be clear, philosophically, about what a picture is. It is a picture, not a pipe. It’s not such a great painting, as paintings go, and the message isn’t that profound, you’d think. Which is why it’s sort of weird that Magritte’s painting has never stopped being popular. You see it, or some version of it, everywhere. And it always sort of tickles you, doesn’t it?

When Magritte painted a picture of a pipe with the words Ceci n’est pas une pipe (“This is not a pipe”) underneath it, he was trying to get the viewer to be clear, philosophically, about what a picture is. It is a picture, not a pipe. It’s not such a great painting, as paintings go, and the message isn’t that profound, you’d think. Which is why it’s sort of weird that Magritte’s painting has never stopped being popular. You see it, or some version of it, everywhere. And it always sort of tickles you, doesn’t it?

I suspect it’s because it is a lesson that has a hard time sticking. Sure, the cortex, our art history lobe, gets it, and yawns, “whatever.” But our limbic lizard brain, like some internal uneducated dumbass, cannot not see a goddamn pipe floating there and still keeps scratching his head over the contradiction. There’s a pipe. But he’s saying it’s not a pipe. Wha’?

Are we that stupid? Don’t we get it already?

Two of my favorite films remind me that no, we do not get it.

We’ve all played the Blade Runner drinking game, where one person drinks a shot every time they see evidence in the film that Deckard is really a replicant, and the other person drinks a shot whenever they find evidence he’s really a human. Well, maybe I’m the only person who plays that drinking game (playing both sides simultaneously). But few films inspire–or used to inspire–such avid debate by fans.

If you’re clever, there are lots of opportunities to drink a “he’s a replicant” shot: Rachel’s “have you ever taken that test yourself?,” Gaff’s origami unicorn and his “You’ve done a man’s job, sir,” at the end. Or, if you’re not so clever (as I wasn’t, the first ten or so times I saw the film), you can watch the movie and have it never occur to you that Deckard might be (gasp) one of the very androids he’s assigned to kill. But even if your cleverer friends laugh at you for being so naïve, you can counterargue that the film is much less poignant if it’s just about a robot who falls in love with a robot. Isn’t the whole moral of the story that maybe humans and robots aren’t so different, that we’re all in the same boat when it comes to love and death?

Making us question whether Deckard “really is” a replicant or “really is” a human is exactly what Ridley Scott wanted viewers to do. He has said as much. All the bits of evidence one way or the other are placed there deliberately, and he made some of his revisions in The Director’s Cut to actually bring the question of Deckard’s identity into clearer focus (the added unicorn sequence, for example—is it an implanted memory or just a metaphor??).

You could sort of compare Deckard to one of those visual illusions that can be seen two ways—one second it’s a duck, the next it’s a rabbit. E.H. Gombrich, writing about the psychology of such illusions, argued that humans can’t help but see them as either-or; you can’t see both a duck and a rabbit at the same time, you see them flop back and forth. But the philosopher Wittgenstein disagreed; he said it is possible, if you try real hard, to say “Well, actually, it’s a duck-rabbit.” Deckard is basically a duck-rabbit. If you try real hard, you can step back, stop drinking, and realize he’s neither human nor replicant. He is a fictional character. There’s no final truth of the matter, no more in the film than what we actually see. Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

Mulholland Drive is the other great solitary drinking game movie. But it’s also one of the most “sociable” films David Lynch has made. One of the best things about it is the conversations it gets one to have with friends who’ve either hated it or been moved by it or both. Like Blade Runner, Mulholland Drive lures us into having conversations about what’s “actually real” in the movie and what parts are “not real,” and to figure out how the not real stuff fits into the real stuff (or vice versa). Is the whole first part of the film a dream and the second part reality? Is the first part the wish-fulfilling rationalization of the murder in the second part? Is fantasy/dream interwoven with reality throughout the whole film? Is Rita “really” just a version of Betty/Diane? It’s impossible not to bite, to play these “which part’s real?” games. As with Blade Runner, figuring out the truth feels important, not just like an empty intellectual exercise, because, however you slice it, there’s a real emotional core to the story. Parts of the film are really moving and heartbreaking. Like witnessing a car wreck, it’s hard sitting back and not getting involved.

Ultimately, all such discussions of the “reality” of Mulholland Drive lead to the Club Silencio scene. A trumpet player comes out on stage playing his instrument, but then he stops playing and the music continues. “No hay banda,” the master of ceremonies explains, “There’s no orchestra. It’s all a recording.” Then, a singer (Rebekah del Rio) comes out on stage and gives a wrenchingly emotional rendition of Roy Orbison’s song “Crying,” and at last collapses – again, her voice continuing with the song. We feel suddenly like real idiots, because we are just as shocked this time as we were just minutes ago with the trumpet player. It’s like we’ve learned nothing. We feel chastised, like a bad student.

Lynch is beating us idiots over the head with the fact that nothing is real in this film. It’s not the depressed and brokenhearted Diane, alone and blowing her brains out in her apartment at the end, who is the “real” woman. She’s a lure for our belief, just like the mascara-dripping sad singer on the stage, before she collapses. Give up on either of them, on any of it, being real. Clearly, Lynch really really wants us to get this message. It’s important we get it, just like it’s important that Betty and Rita really get it, and from their tears watching the singer collapse in Club Silencio, you can tell that it hits them hard.

What is so important about this message though? Is Lynch just making some kind of clever philosophical statement about Art? I don’t think so—Lynch is more serious (and even down-to-earth) than that. So is Ridley Scott. And so was Magritte. Could it instead be that, by making us see our own complicity in being fooled by a movie or a painting, these guys were trying to show us something about life and our own complicity in being fooled there too?

Maybe we need to keep going back and repeating this lesson—go back to Club Silencio and re-learn the lesson of the collapsed singer on the stage. Oh right! It’s not real! And then keep re-learning it. Maybe eventually it will stick.

I love the BladeRunner drinking game !! But yeah I get the message but still looks like a pipe to me 😉