Synchronicity Machines and Psychotropies of Spacetime

It is because we are lost, decentered by the ego and conceptual symbolic thought, that many mystical or religious experiences involve a sudden amazement of what Ram Dass famously called “being here now,” or simply presence. What is really the most obvious fact, our simple existence somewhere, our conscious awareness, suddenly comes alive as something new and fascinating: “I am here.” Every term in that sentence takes on a numinous quality or becomes a sublime mystery: I, me, what is that? What is it to be? What is here? Where is here? Where was I before and why didn’t I feel so strongly like I was anywhere? How did my being-here-now suddenly feel so amazing?

Space itself contains psychotropic properties that can be extracted, distilled, and delivered to users.

And then, just as quickly as we became aware of it, clear presence fades, and we are clouded again in muddy thoughts of small-s self (the imaginal-symbolic murk I have called the “Solaris mind”).

Mystics and meditators get addicted to these transient clear moments of presence outside and beyond imagination and language, trying to reclaim, prolong, and intensify them. It can become an active daily project. Besides meditation and yoga, peak or flow experiences in sport may strip away mental and behavioral barriers to being in the present moment, temporarily dissolving the obstructing ego. Sex and war can do it, or, I imagine, a life-or-death duel where “it was either him or me.” And of course, some use drugs to strip away the ego and attempt to be in the Now.

In his excellent book On Deep History and the Brain, historian Daniel Lord Smail recommends viewing all of human history through the lens of psychotropy. He doesn’t mean literally that drug-taking made us what we are—the argument sometimes made by entheogen enthusiasts—but rather that nearly everything we do alters our brain chemistry, either restoring balance to, or deliberately un-balancing, the inner neuroendocrine ensemble.

Being efficient on the job, listening to music, watching an event unfold on the news, getting in an argument or a fight, or gossiping with neighbors (not to mention the basics like sex and eating and sleeping) are all “psychotropic” in the sense that they modulate our internal mixing-board console with its dopamine and serotonin and norepinephrine and endorphin and endocannabinoid (and many, many other) sliders, like a sound technician in a recording studio. And most of the things we say or do to other people are similarly meant to operate on their internal mixing boards. Among a handful of random examples, Smail mentions the rise of the novel in the 18th century, which introduced a new and troubling “solitary pleasure” that worried cultural authorities in ways not too different from the “reefer madness” fears around marijuana in the 1930s.

Being efficient on the job, listening to music, watching an event unfold on the news, getting in an argument or a fight, or gossiping with neighbors (not to mention the basics like sex and eating and sleeping) are all “psychotropic” in the sense that they modulate our internal mixing-board console with its dopamine and serotonin and norepinephrine and endorphin and endocannabinoid (and many, many other) sliders, like a sound technician in a recording studio. And most of the things we say or do to other people are similarly meant to operate on their internal mixing boards. Among a handful of random examples, Smail mentions the rise of the novel in the 18th century, which introduced a new and troubling “solitary pleasure” that worried cultural authorities in ways not too different from the “reefer madness” fears around marijuana in the 1930s.

Although Smail doesn’t mention this, people throughout history and even prehistory have devised countless innovations in art and architecture and even landscaping to recruit and deploy the Kantian frameworks of Space and Time in ways that can induce the profound or even numinous feeling of “being here now.” These innovations were full-on psychotropic, and they were decisive turnings in our cultural and spiritual evolution.

The Timothy Leary of Perspective

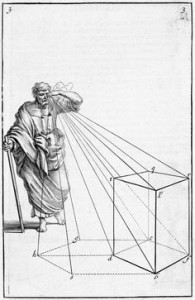

I can’t forget the day in art class in fourth grade, when Mrs. Este taught us how to draw a building in perspective. She had each of us place a dot in the center of the paper and then use a ruler to draw a vertical rectangle to the right of the dot, which would become the front of the building. For the oblique side wall of the building, she had us extend the ruler from the top and bottom corners of the building toward the vanishing point, drawing short lines “receding” in space toward it. We then finished our building with another shorter vertical line connecting these two lines at the back. We then drew a horizontal line through that vanishing point and “behind” the building, representing the distant horizon, and finished the building off with rows of windows—the oblique ones likewise receding toward the vanishing point using a ruler.

Perspective turned seeing into an intensely individualistic and solitary form of enjoyment. What viewers were enjoying was not “the view” that paintings gave them, but a new kind of awareness of themselves as individuals.

That day in art class was unforgettable because it was an astonishing revelation, a paradigm shift in my understanding of myself in relation to the world, not to mention my self-confidence as a creator of culture. Just by making parallel lines converge on a central vanishing point, even I, a mere fourth-grader, could make a pretty decently “realistic” drawing of a building. Little did I know that this lesson, and the profound “aha” feeling that came with it, was reliving one of the most storied discoveries-slash-inventions in the history of art.

The first full-on perspectival illusion was created by Filippo Brunelleschi, a brilliant young sculptor, and later architect, who sometime around 1413 painted two pictures of buildings in his town, Florence, that were in perfect, mathematically precise perspective. These panels, which unfortunately no longer exist, are reported to have had a mind-blowing effect on his contemporaries. Other than Louis Lumiere’s 1895 Arrival of the Train—which is rumored, possibly inaccurately, to have caused audiences to panic in fright—I am not aware of any other unveiling in the history of art that so resembles the delivery of a hallucinogen.

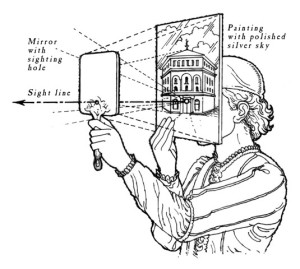

The first of Brunelleschi’s panels was a piece of wood about the size of a record album, depicting the octagonal Baptistery of Florence Cathedral. It was more a contraption than a mere painting: It had a tiny hole drilled through the exact center of the panel (corresponding to the vanishing point). The viewer was made to hold the panel up to his face, almost like a mask, and look through the peephole from the back, at a mirror held out in front of the panel at arm’s length. Instead of painting the sky above the baptistery, Brunelleschi applied a reflective silver foil to reflect the real sky.

The first of Brunelleschi’s panels was a piece of wood about the size of a record album, depicting the octagonal Baptistery of Florence Cathedral. It was more a contraption than a mere painting: It had a tiny hole drilled through the exact center of the panel (corresponding to the vanishing point). The viewer was made to hold the panel up to his face, almost like a mask, and look through the peephole from the back, at a mirror held out in front of the panel at arm’s length. Instead of painting the sky above the baptistery, Brunelleschi applied a reflective silver foil to reflect the real sky.

The panel no longer exists, and we have only various written recollections by Brunelleschi’s contemporaries, attesting to its awe-inspiring, even life-altering impact on them. The most detailed account is that of his biographer, Antonio Manetti, who wrote that seeing the Baptistery this way was something truly special, an experience to be repeated: “To look at it, under the various specified circumstances … it seemed that one was seeing truth itself; and I held it in my hands and saw it several times in my own day, and so can testify to it.”

Brunelleschi was thus like the Timothy Leary of perspective—getting friends and fellow intellectuals and artists in Florence to try it, savoring their amazement, and acting as kind of a prophet of this new technique that, when done right, could move viewers’ minds toward introspection in not only a delightful but also a spiritual way.

One at a Time

Brunelleschi wasn’t simply showing his friends a new scientific principle of art; he was actually connecting them to their presence. And since the intensely private experience he gave them was witnessed by eager, amused onlookers, there was an important confusion about which aspects of this psychotropic experience were more important, the public or the private.

Perspective, with its power to make one end up solitary, eccentric, melancholy, and poor, was the intellectual opiate of its day.

Early work in perceptual psychology showed that seeing things through peepholes does something special to the viewing experience, tricking the mental and visual system into believing in the “truth” of the viewed scene in a much more powerful way than if we saw it in more typical, unrestrained conditions. Simultaneously, a peephole enforces a sense of privacy or solitude—only one person can look through a peephole at a given time, giving you the feeling that the view you are seeing is intended only for you—kind of like the “door in the law” in Kafka’s famous Gnostic parable.

During the first decades of perspective’s existence, people believed that to see the 3-D illusion accurately it wasn’t enough to just stand in front of it; your eye had to occupy a very precise point in space directly opposite the picture’s vanishing point—called the “station point”—and if you didn’t, all you would see, as Leonardo da Vinci put it, was “confusion.” This notion is probably why Brunelleschi designed his demonstration to be viewed the way he did. It took a while for artists to figure out that the imagination can compensate for being off-center with respect to a perspectival rendering, as we now intuitively know from our experience not having the exact center seats in a movie theater; even if we have to sit all the way on the aisle, the movie’s still “in perspective.”

In fact, what Brunelleschi’s contraption really did was enforce and reinforce the idea that perspective demands being right in one exact spot, and thus (by extension) that the viewer is alone in his experience of the world—a singular, solitary experiencer. It’s kind of the implicit corollary of “being here now”: Only a single person, you, can be right here, right now, in this exact spot, seeing what you’re seeing. By awakening the viewer to that amazing fact, perspective turned seeing into an intensely individualistic and solitary form of enjoyment. What viewers were enjoying was not “the view” that paintings gave them, but a new kind of awareness of themselves as individuals.

In fact, what Brunelleschi’s contraption really did was enforce and reinforce the idea that perspective demands being right in one exact spot, and thus (by extension) that the viewer is alone in his experience of the world—a singular, solitary experiencer. It’s kind of the implicit corollary of “being here now”: Only a single person, you, can be right here, right now, in this exact spot, seeing what you’re seeing. By awakening the viewer to that amazing fact, perspective turned seeing into an intensely individualistic and solitary form of enjoyment. What viewers were enjoying was not “the view” that paintings gave them, but a new kind of awareness of themselves as individuals.

The invention-slash-discovery of perspective in the 1400s was the biggest-ever paradigm shift in visual representation, defining the way we see the world, and ourselves, ever since. It turned what used to be a taken-for-granted public experience (seeing) into an intensified solitary pleasure, as well as creating a whole new visual code or language where oppositions like near/far or flat/deep space carried specific meanings. The perspective code actually required the implicit “unitary seeing subject” (in the words of philosopher Brian Rotman) the same way a spoken utterance always carries an implied “you” as its addressee.

The Capitalist Subject

It is no coincidence that perspective and the individual and individualistic culture-consumer it helped create was born right when capitalism was emerging in Europe. Perspective’s implicit conceptual model—light rays entering a private brain-space via the eyes—informed modern European ego-bound psychology and philosophy and the “centering of the subject.” Paintings at the time displayed valuable commodities, and the virtual 3-D space in those paintings was described by John Berger as like a safe set into a wall.

It is no coincidence that perspective and the individual and individualistic culture-consumer it helped create was born right when capitalism was emerging in Europe. Perspective’s implicit conceptual model—light rays entering a private brain-space via the eyes—informed modern European ego-bound psychology and philosophy and the “centering of the subject.” Paintings at the time displayed valuable commodities, and the virtual 3-D space in those paintings was described by John Berger as like a safe set into a wall.

It is surely also no coincidence that the most popular subject matter for paintings at the time was the Annunciation to Mary, because this is a scene in which an individual is singled out and addressed by something not of this world—in other words, exactly what a perspective picture is. Whenever you see a Renaissance painting of that scene from the Gospel of Luke, you’ll see a powerfully receding space, a pyramid of parallel lines receding to an actual or implied vanishing point in the center, with the angel Gabriel on the left addressing Mary on the right, forming a kind of implicit cross structure.

Mary herself is always shown in one of a few subtly distinct postures reflecting her unfolding reaction to what the angel is telling her—surprise, bewilderment, inquiry, finally humble acceptance of her mandate to bear God’s son. With perspective, a picture had to implicitly show a single “now,” a single instant in time, even if the moments of the story were implicitly just a few brief seconds apart (as in the Gospel narrative). No longer did paintings depict cartoon-like series of moments or a vague spread-out timespan, as Medieval paintings had done.

Mary herself is always shown in one of a few subtly distinct postures reflecting her unfolding reaction to what the angel is telling her—surprise, bewilderment, inquiry, finally humble acceptance of her mandate to bear God’s son. With perspective, a picture had to implicitly show a single “now,” a single instant in time, even if the moments of the story were implicitly just a few brief seconds apart (as in the Gospel narrative). No longer did paintings depict cartoon-like series of moments or a vague spread-out timespan, as Medieval paintings had done.

The intensified feeling of presence that perspective awakened to viewers is equivalent to awakening to what we would now call “consciousness,” as consciousness is tantamount to being aware that you exist in a particular place and have a (unique) point of view. The Renaissance viewer may have unconsciously identified with Mary during the Annunciation, feeling uniquely “addressed” and, in some peculiar way, divinely favored, by this perspectival awakening.

Space-Abuse

In other words, space itself contains psychotropic properties that can be extracted, distilled, and delivered to users through procedures like perspective paintings. This raises the question: Can space be abused? The answer is, unfortunately, yes. The 16th-century art historian Georgio Vasari records the case of at least one “addict” who was destroyed by the perspective fad that had swept through the artistic community of the 15th century.

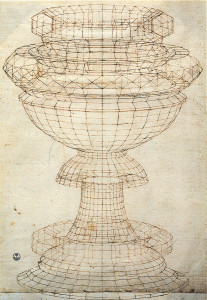

“The most captivating and imaginative painter to have lived since Giotto,” Vasari wrote, “would certainly have been Paolo Uccello, if only he had spent as much time on human figures and animals as he spent, and wasted, on the finer points of perspective.” Among Uccello’s sketches and notebooks are astonishing studies of circular and polygonal objects, many of which look exactly like nothing else but solids that have been wire-modeled on modern animation or design software. He liked to focus on solid objects such as hats much more than on the people wearing them, and it is a woodenness in some of his paintings that prompted Vasari to criticize the painter for his overriding interest in this special effect.

“The most captivating and imaginative painter to have lived since Giotto,” Vasari wrote, “would certainly have been Paolo Uccello, if only he had spent as much time on human figures and animals as he spent, and wasted, on the finer points of perspective.” Among Uccello’s sketches and notebooks are astonishing studies of circular and polygonal objects, many of which look exactly like nothing else but solids that have been wire-modeled on modern animation or design software. He liked to focus on solid objects such as hats much more than on the people wearing them, and it is a woodenness in some of his paintings that prompted Vasari to criticize the painter for his overriding interest in this special effect.

Vasari actually blamed Uccello’s excessive interest in perspective for his failure in life and for various unhappy tendencies in his disposition. He writes: “Artists who devote more attention to perspective than to figures develop a dry and angular style because of their anxiety to examine things too minutely; and, moreover, they usually end up solitary, eccentric, melancholy, and poor, as indeed did Paolo Uccello himself.” If Brunelleschi was perspective’s inventor, then without a doubt Uccello would have to be considered its first casualty. When he died, Vasari writes, he left behind “a wife who told people that Paolo used to stay up all night in his study, trying to work out the vanishing points of his perspective, and that when she called him to come to bed he would [ignore her, saying]: ‘Oh, what a lovely thing this perspective is!’”

So perspective, with its power to make one end up solitary, eccentric, melancholy, and poor, was the intellectual opiate of its day. To suggest that the condition of melancholia was brought on by the loss of sleep and conjugal pleasures that befell the artist or theoretician in their excitement over perspective would not actually be so far from the truth—the inherent paradoxes of perspective (being-there yet not being there, seeing alone yet among others, etc.), and the inability of the mind to get around them, became something of a metaphor for insoluble paradox in general, the sort of thing that plagued students, scholars, and monks who spent too much time alone with their books.

So perspective, with its power to make one end up solitary, eccentric, melancholy, and poor, was the intellectual opiate of its day. To suggest that the condition of melancholia was brought on by the loss of sleep and conjugal pleasures that befell the artist or theoretician in their excitement over perspective would not actually be so far from the truth—the inherent paradoxes of perspective (being-there yet not being there, seeing alone yet among others, etc.), and the inability of the mind to get around them, became something of a metaphor for insoluble paradox in general, the sort of thing that plagued students, scholars, and monks who spent too much time alone with their books.

To this day, in photography and film, extreme or forced perspective using a fisheye (extreme wide-angle) lens is part of our standard visual symbolism for isolation, depression, anxiety, and even madness. Stanley Kubrick’s films, for example, provide endless good examples of this.

To the Oculus Rift

Every revolution in visual experience has repeated the pattern of perspective: initially providing a new and amazing or inspiring experience (of “truth itself,” as Manetti put it), opening us to a new way of seeing the world, before gradually becoming taken for granted. We develop tolerance to special effects when we see them every day.

Any two things can be joined by a line; when three things are all joined by that same line, there is a coincidence; when that coincidence seems to address you individually, it is, effectively, a “synchronicity.”

The natural outgrowth of perspective, for example, was the refinement of optical theories that led quickly to the development of lenses for microscopes and astronomy and, ultimately, the camera. Viewers of the first daguerrotypes had similar mind-expanded reactions to those that accompanied the first perspective paintings, and anthropologists have reported interesting responses among indigenous peoples unfamiliar to photographs when first shown them: They may not know what they are looking at, but if and when it suddenly clicks for them that “this is how it would appear if I were standing in a specific spot looking at X,” it does so with a kind of euphoria—the psychological effect of a conceptual paradigm shift.

Subsequently, movies and television combined the psychotropy of photographic reproduction with the ancient powerful psychotropies of story and music to produce a highly compelling and addictive drug cocktail. The next phase in the historical unfoldment of presence and the technologies for producing it is virtual reality, of course. Although immersive VR goggles have been around for over two decades in rudimentary form, there has been an “uncanny valley” quality to them that has tended to make the VR experience somewhat aversive, even nauseating. But according to all the advance hype, the next generation is poised to surpass these difficulties and represents a milestone in eliciting a truly euphoric feeling of presence. This is surely going to be the next techno-drug … at least, before we become tolerant to it.

Countless culture critics have pointed out the drug-like nature of electronic and visual media, and that’s not solely a function of the constant dopamine stimulation caused by motion and fast-cutting. Even acting is a kind of ancient shamanic “special effect”: A living, known person assuming a persona of someone else, such as a hero or a spirit or a god (even just dad in a Santa Claus suit), is a transformation that to a child is still amazing; it is even a bit amazing to adults when we see a movie or TV personality in real life—a mildly pleasurable cognitive dissonance that surely accounts partly for our fascination with celebrities (i.e., mentally juxtaposing the fake and real, savoring the “aura” that Walter Benjamin famously observed surrounds an “original” that has been widely reproduced).

Countless culture critics have pointed out the drug-like nature of electronic and visual media, and that’s not solely a function of the constant dopamine stimulation caused by motion and fast-cutting. Even acting is a kind of ancient shamanic “special effect”: A living, known person assuming a persona of someone else, such as a hero or a spirit or a god (even just dad in a Santa Claus suit), is a transformation that to a child is still amazing; it is even a bit amazing to adults when we see a movie or TV personality in real life—a mildly pleasurable cognitive dissonance that surely accounts partly for our fascination with celebrities (i.e., mentally juxtaposing the fake and real, savoring the “aura” that Walter Benjamin famously observed surrounds an “original” that has been widely reproduced).

And harvesting spacetime to induce a drug-like sense of presence probably goes back to the very origins of religion.

The Druid Inside

Consider the range of druidic psychotropies afforded by megalithic observatories. Although the individual standing stones that dot the British and Continental European landscape were probably wayfinding tools for neolithic travelers and traders, the large stone complexes like Stonehenge or Callanish on the Scottish Isle of Lewis certainly had an astronomical function: Depending on the particular observatory, on significant days like solstices and equinoxes, the sun might be seen, to the observer standing at the exact center of the circle, to rise or set directly past a specific feature on the horizon beyond a specific stone or through a specific gap. An imaginary line was thus created that connected the viewer to the heavenly body, via a significant landmark, right at a particular significant moment in time.

Synchronicity, in a sense, is the ultimate solitary pleasure

In the modern world, we have become mostly tolerant of holiday sunrises and sunsets, so it is natural for today’s ethnoastronomers to focus on the mundane practical uses of reckoning solar and lunar events for timekeeping—that is, maintaining the ritual calendar and knowing when to plant crops—or else they chalk ancient astronomy up to beliefs about the spirit world. Timekeeping and astrological or shamanic practices were no doubt real payoffs of attention to the night sky and to the rising and setting of heavenly bodies, but those explanations pass over the crucial viewing experience of the ancient astronomer, the “awakening to presence” aroused by experiencing significant spacetime alignments, not to mention the rewards of delivering such experiences to a mystified laity.

Any two things can be joined by a line; when three things are all joined by that same line, there is a coincidence; when that coincidence seems to address you individually (like Gabriel addressing Mary), it is, effectively, a “synchronicity.” You might even call a stone circle a synchronicity machine: a material apparatus for creating a significant coincidence between an observer and a geo-cosmic conjunction. We must not forget its contrivance, however—the “coincidence” wouldn’t exist but for that apparatus. This is exactly like Brunelleschi’s demonstration, with its imaginary connection between the eye and the vanishing point (symbolically associated with God), via the peephole. Coincidences and synchronicities feel both uncanny and reassuring to us, and that must have been true for ancients observing the solstices in their temple complexes—observing, both in the sense of watching and in the sense of celebrating or commemorating.

At the center of observatories were living people—perhaps just the druidic elite and nobility, or perhaps everyone, one at a time—viewing and experiencing those alignments at precise moments on specific days of the year, and thus feeling their consciousness acutely and sublimely. Prehistoric astronomy would have generated a personal experience in living human beings that translated directly into perennial philosophical and spiritual terms of cosmic communion and simple presence.

At the center of observatories were living people—perhaps just the druidic elite and nobility, or perhaps everyone, one at a time—viewing and experiencing those alignments at precise moments on specific days of the year, and thus feeling their consciousness acutely and sublimely. Prehistoric astronomy would have generated a personal experience in living human beings that translated directly into perennial philosophical and spiritual terms of cosmic communion and simple presence.

These ancient synchronicity machines were every bit as ideological as Renaissance paintings or photography or cinema: They were material (and materialistic) contrivances that capitalized on the brain’s susceptibility to illusion, especially the illusion of having or being a “self,” to mystify and amaze. There were always men behind the curtain who had created this expensive experience as an instrument of material, social, and religious power as well as an expression of scientific and technical mastery.

Humbler everyday experiences of meaningful coincidence also draw power from the way they single us out as individuals. As I’ve been arguing in this blog, in such experiences, the man behind the curtain is simply ourselves, displaced in time. The meaning-making, precognitive brain is the ultimate synchronicity machine, the real “acausal connecting principle.” We mystify ourselves by playing hide and seek with our presence, facilitated by our culturally-imposed non-belief in precognition. And there is always lone experiencer at the center, enjoying its perplexity at being addressed by the cosmos or fate. Synchronicity, in some sense, is the ultimate solitary pleasure.

Another good one.

In response to your writing (and also to some extent to Chris Knowles’), I’ve been thinking for quite some time that Jung’s definition of synchronicity, “An a-causal connecting principle,” could be read as a placeholder for “the self that perceives the connection.” I’m not sure that it necessarily requires the precognizing brain to “see it that way,” but that certainly is the major contribution you’ve been working on.

My experience with structures that are constructed, intentionally, to be round — the Newark Circle in Ohio, a Boy Scout Order of the Arrow outdoor enclosure where I attended a camping festival in western Missouri or eastern Kansas, and a small urban park in the city where I live — has been that they offer a consistent and unique consciousness-altering property that clearly feels energetic, and in some cases (the Order of the Arrow enclosure, the city park, and a couple of capitol domes I’ve stood under) acoustic. A friend of mine reports that “Woodhenge,” a part of the Cahokia complex in western Illinois just across the Mississippi from St. Louis has a similar effect.

A friend of mine lives on about 80 rural acres in a nearby county, on top of a bluff on the Missouri river. He recently put up a standing stone he had retrieved from a roadside ditch with his backhoe. He talks about his interactions with the environment in fairly animistic terms, and his story about retrieving and setting the stone goes something like this: this big piece of limestone (about 5 feet tall and roughly 1 ft in diameter) “jumped into” the front-end loader on his backhoe, and then “jumped out” at a particular point up his long, hilly driveway. That wasn’t the spot my friend had chosen, but when he tried to move the stone again, he had no luck getting it back into the hoe. So, he decided he would stand it, right there, the logic being that that’s where the stone *wanted* to be.

I saw the stone a couple of times in it’s laying-on-the-ground state and the hole he dug to stand it in. My impression was, “That’s going to be a challenge to get up.” He even asked me to come help stand it, but it turns out he didn’t need any help; when it got dry enough to stand the stone, it easily stood, like it wanted to be there.

All anthropomorphisation, of course. However, when I finally got out to see it, I was struck by the subtle and palpable way the addition of this ‘unnatural’ standing stone altered my perception of an already very beautiful landscape. Its addition changed the way *everything* looked.

Thinking of stuff I’d read about Stonehenge and Gobekli Tepe, I picked up a wooden-handled hoe lying on the ground, and gently struck one side of the (now) plinth. My friend told me he thought to himself, “What’s Akh doing?” What I was doing was finding out that, yep, this tall rock “rang” when struck. I want to take a couple of rubber drum-mallets with me next time I go out.

All this is by way of replying to your observation that most solitary standing megalithic stones were probably “way-marks:” “Yes, *but* even standing just one rock in a landscape can alter an individual human’s experience of the ‘presence’ *of* and one’s own ‘presence’ *in* a landscape.” This making sense?

I very much enjoyed listening to your discussion with Alex Tsakiris on *Skeptiko,* and I couldn’t help be a little amused by how he tried to get you to “bite” on NDE because, in his perspective, NDE experiences clearly demonstrate that consciousness doesn’t need a living brain to be produced from, while your message on the Phil Dick circuit is that “we are probably going to find specific neural circuitry involved with precognition.”

This brought to mind something that has stuck with me since I really began to “get” in inadequacy of a strictly materialist ontology: We’re never going to get rid of the extent that materialism seems to have worked (viz: brain scans, thermonuclear reactions, space travel). That is to say, even in the face of the evidence provided by the existence of high functioning, above-average hydrocephalics, the mountains of evidence that for average folks, there are very consistent, useable, precise correlations between neural states, mental/emotional states, and behaviors. Even if we can’t complete the picture of how nervous system and consciousness are related, those correlations are not going away. Observing that there appears to be a correlation between a material event and an experience doesn’t make one necessarily a materialist.

Tsakaris has done a great job of collecting good work on NDEs and putting it out for all to see. After listening to your conversation with him, something like this occurred to me: We have experience reports from people who are officially brain dead, but whose brains “came back to life.” They give veridical reports of stuff that was going on while they were officially brain dead. What we don’t have (well, not in the same way, anyway) is the experiential reports from people who become brain dead, and don’t come back to life.

One of Tsakiris’ concerns involved the possibilities of/existence of non-corporeal conscious entitities, something a purely materialist ontology can’t deal with. I have been in different spots that helped me “get” the idea of “genius loci,” and part of what I’m saying in response this particular essay by you, including the digression about the standing stone, is, “Very interesting that you point out the relationship between our experience of the environment and our sense of ‘presence.’ My feeling at the moment is, it’s pretty interesting that something as “simple” as a standing stone – never mind a stone circle – can alter the sense of presence of a ‘genius loci.’