What’s Expected of Us in a Block Universe: Intuition, Habit, & ‘Free Will’

Ted Chiang is an SF writer after my own heart. At every stage in my own investigation of time loops, someone sends me yet another Chiang story that addresses exactly the issues I’ve been working on. What’s more, his stories seem to act as attractors for precognitive and time-looping experiences. I’m sure his new collection Exhalation, which compiles some time-related stories that have been floating around in various publications and on the Internet for several years, will have already precipitated countless precognitive dreams.

“What’s Expected of Us” is one of those stories. This story, originally published in Nature in 2005, is about a little device with a light, a button, and a precognitive circuit (or “negative time delay”) linking them. The light goes off one second before the button is pressed, and cannot be fooled no matter how hard the user tries. Users treat it like a game, trying to “beat” or outwit the light, but find they cannot. The device becomes super popular, people play with it addictively, but roughly a third of users succumb to a kind of hopelessness and immobility called “akinetic mutism,” because of what the device has taught them about the nonexistence of free will, the futility of trying to change their fate. “Like a legion of Bartleby the Scriveners, they no longer engage in spontaneous action.”

“What’s Expected of Us” is one of those stories. This story, originally published in Nature in 2005, is about a little device with a light, a button, and a precognitive circuit (or “negative time delay”) linking them. The light goes off one second before the button is pressed, and cannot be fooled no matter how hard the user tries. Users treat it like a game, trying to “beat” or outwit the light, but find they cannot. The device becomes super popular, people play with it addictively, but roughly a third of users succumb to a kind of hopelessness and immobility called “akinetic mutism,” because of what the device has taught them about the nonexistence of free will, the futility of trying to change their fate. “Like a legion of Bartleby the Scriveners, they no longer engage in spontaneous action.”

People used to speculate about a thought that destroys the thinker, some unspeakable Lovecraftian horror, or a Gödel sentence that crashes the human logical system. It turns out that the disabling thought is one that we’ve all encountered: the idea that free will doesn’t exist. It just wasn’t harmful until you believed it.

This wonderful little story cuts to the heart of the issues, as well as misconceptions, that surround the question of free will and the threats to it that we imagine are posed by precognition in a block universe, where the future in some sense already exists.

Americans have trouble with anything that appears to threaten the idea of free will. Ours is a highly freedom-loving and individualistic society, and we love the idea that we are free agents, willful determiners of our lives. We think of ourselves as cars who can go anywhere we please, even off-road, not trains fixed to a single track. If we think of the future as “already” holding something in store for us, we delimit that something to destiny, a kind of dotted line around the person we might become but aren’t obliged to. A destiny is a future that awaits our freely willed actions to fulfill or not fulfill, depending. This is in sharp contrast to the ancient notion of fate as a preordained future that will always outwit our best efforts at evasion. Classical tragedies like Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex were thought experiments about fate and how we fulfill it precisely by trying to escape it.

“What’s Expected of Us” is a mini Oedipus Rex for an age of fidget-spinners. But we don’t need to look as far back as fifth Century BC Athens for models for the Predictor. The first thing Chiang’s story reminds me of—and I’d bet the author had it in mind when he wrote the story—is an astonishing 1983 discovery by neuroscientist Benjamin Libet: The nerves in participants’ fingers readied to fire (“lit up” you might say) a fifth of a second before participants consciously decided to move their finger. Libet’s discoveries prompted other psychologists to prove that we are not really masters in our house. Experiments by Daniel Wegner and others seemed to show that we instead take credit for actions per our culturally ingrained ideas of agency. The ego sees something it likes—a successful motor action, say—and proudly goes “I did that.” It sees something it didn’t like, like tripping and falling, and chalks it up to accident or to some external force or influence impinging on it.

Conscious will as studied in psychology laboratories is not exactly the same thing as the philosophers’ free will and the question of physical determinism. But it offers an interesting entry point to the question of what we really lose by jettisoning that philosophical security blanket of imagining that the future remains open ended and under our control. If the conscious mind is a spectator, what is it we’re really talking about when we’re talking about free will? Is “akinetic mutism” really the result of giving up on our belief in it?

Seize the Fish!

In Chiang’s story, Predictor users slump into apathy and silence because they decide their actions (versus nonactions) don’t matter. And part of their problem is they can’t shake their feeling of free will even when they know it isn’t “real” in some larger sense. Lying in bed and not responding to one’s surroundings is just as much an action as getting up and seizing the day (“Carpe diem!“) in the belief that we are agents of our lives—because our thoughts and interpretations are just as much “enacted” as our physical movements.

But what the Zen masters of China and Japan discovered is that direct experience of the illusory nature of free will actually leads to liberation, not apathy. There is a training-wheels phase, though: Trying to escape the question of free will/no free will and directly experience pure spontaneity is a familiar experience for any beginner at Zen practice, in fact. What one discovers is the ridiculousness of the pose of “not acting.” You can’t escape your thoughts. Nor can you escape the will of your body. (Hunger alone will drive you to go to the kitchen and eat, ignoring your mental bafflement: “hey, is this freely willed, or not??”)

But what the Zen masters of China and Japan discovered is that direct experience of the illusory nature of free will actually leads to liberation, not apathy. There is a training-wheels phase, though: Trying to escape the question of free will/no free will and directly experience pure spontaneity is a familiar experience for any beginner at Zen practice, in fact. What one discovers is the ridiculousness of the pose of “not acting.” You can’t escape your thoughts. Nor can you escape the will of your body. (Hunger alone will drive you to go to the kitchen and eat, ignoring your mental bafflement: “hey, is this freely willed, or not??”)

Ultimately, passively observing the flow of stuff in our head, and detaching ourselves from our actions and their outcomes, is highly freeing, not to mention empowering. What serious meditators discover is that, unburdened from the baggage of thinking about their freedom or unfreedom, their thoughts become more rewarding and their actions and words more skillful. The less free we imagine we are, the more free we feel. It’s the same joy anyone feels whenever they practice any complex skill and become so good at it that the practice becomes effortless, performed in a state of flow. Shao-lin kung-fu masters are not worried about their free will. Neither are the wise heptapods in the movie Arrival, based on Chiang’s “Story of Your Life.”

The akinetic mutists of “What’s Expected of Us” are simply stuck in that awkward in-between period, on the way to becoming enlightened Zen masters or heptapods basking blissfully in the eternity of the block universe.

The question of human precognition and free will should not be divorced from the question of skill performance. Anyone who knows how to drive a car well, be super witty on a date, or swiftly change a baby’s diaper with one hand knows that we are most effective when we don’t think about what we are doing but just do it. Research on “psi” also shows that it is an unconscious, un-willed function or group of functions. Laboratory experiments strongly support something like presentiment (“feeling the future”), and there is reason to think it could be a pervasive feature or even a basic underlying principle of our psychology. I am not the first to suggest that Libet’s findings actually reflect the tip of the iceberg of presentimental functioning.

Indeed, people who express strong “intuitive” ability often seem to do so in the context of some automatized and highly enjoyable/thrilling motor skill—piloting a plane, martial arts, mountain climbing, but also things like musical performance, stage magic, and other arts (including hammering away at a typewriter for a penny or a dollar a word). I consider dowsing to be the model, the most basic form (or stem cell) of psi as presentiment/precognition: using motor reflexes to tap into a forthcoming reward via the ideomotor effect. And whether you are a race car driver, a remote viewer, or a dowser, self-consciousness that might include an awareness of “making choices” is the last thing you want.

The relation of our conscious will to our skilled actions may be something like a time loop, in other words. We go through life behaviorally divining successful or rewarding outcomes, which we then reflect on afterward, perhaps misinterpreting that retrospective reflection as agency. But another way of putting this is that we may be “pulling our meat puppet’s strings” from a point farther along our timeline. What we interpret in hindsight as our will or intention is really the reward of having had an accurate premonition of a future successful action.

Caudate-Putamen

Interestingly, there is now potentially some neurobiological support for the linkage of “psi” specifically with compulsive, habitual, or automatic—in other words, distinctly not “consciously willed”—behaviors.

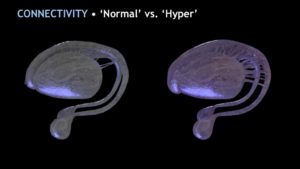

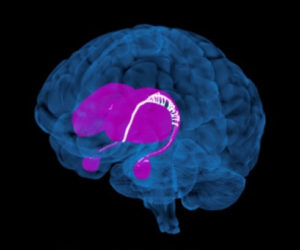

This past winter, a few blogs including Terra Obscura announced the highly intriguing findings of Garry Nolan (Rachford and Carlota Professor in the Dept. of Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford School of Medicine) and forensic neurologist Christopher “Kit” Green (Depts. of Diagnostic Radiology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences at Wayne State School of Medicine and Detroit Medical Center) on a brain area called the caudate-putamen. In the course of working with a population of 135 high-performing military and intelligence personnel who had suffered injuries from anomalous encounters in the line of duty, the researchers noted an additional feature in a few patients’ MRIs. Twenty of the most high-functioning and “intuitive” of this group, as determined from medical and psychological records, displayed significantly enhanced connectivity between their caudate and putamen, compared to the general population.

This past winter, a few blogs including Terra Obscura announced the highly intriguing findings of Garry Nolan (Rachford and Carlota Professor in the Dept. of Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford School of Medicine) and forensic neurologist Christopher “Kit” Green (Depts. of Diagnostic Radiology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences at Wayne State School of Medicine and Detroit Medical Center) on a brain area called the caudate-putamen. In the course of working with a population of 135 high-performing military and intelligence personnel who had suffered injuries from anomalous encounters in the line of duty, the researchers noted an additional feature in a few patients’ MRIs. Twenty of the most high-functioning and “intuitive” of this group, as determined from medical and psychological records, displayed significantly enhanced connectivity between their caudate and putamen, compared to the general population.

The work of this sample of persons is secret, as are the circumstances of the injuries that brought them to the attention of the researchers in the first place; but the implication is that those who showed the enhanced connectivity are the kinds of people who have “Spidey sense,” who could instinctively guide you down the right path in enemy territory because they sense danger down the left. A sample of remote viewers for whom MRI scans were available all showed the same caudate-putamen biomarker.

The caudate-putamen, also known as the dorsal striatum, is thought to be a kind of “hub” that integrates information from across the brain and translates that information into motor actions. Nolan and Green’s sample show exceptionally high parallel and rapid processing of what in very recent years has emerged as functions of the dorsal striatum’s receipt of incoming sensory information, and subsequent integration in the prefrontal cortex.

In presentations of their finding, the researchers have called the dense, spoke-like connectivity in these high-performing individuals an “antenna”—there is indeed something suggestive of an antenna in its visual appearance—but they have not tested the notion of any electromagnetic receiving or transmission capability, and they recognize that its precise functional role in intuitive skill performance is a matter of speculation at this point. But they did not find this feature at all in brain scans from a retrospective sample of over 300 “ordinary” people—that is, patients who had no medical histories of high executive functioning, and who served as single-blind controls.

And interestingly, it appears to run in families. The researchers fortuitously had access to siblings, parents, and children of some subjects—3 or 4 family members in a few cases—and the MRI finding was present in those individuals also. Consequently, Nolan established a genetic pilot study that is now underway, to learn more about this feature and its heritability. It is still unknown whether and to what extent life experience or training may also influence it (i.e. the brain’s plasticity). When helpfully answering my questions by email, they also stressed that their finding about the caudate-putamen in this sample has not been peer-reviewed, nor yet published, nor subjected to double-blind verification.

“Antenna” is a sexy term, and it got the attention of many people who are interested in intuitive and psychic functioning. But if further research supports this brain feature and its relation to high performance, I have a hunch “Predictor” might turn out to be an even better term for what Nolan and Green have found.

The Jouissance System

The study of psychic phenomena has always adopted some model of information-transfer, rooted in telecommunications technologies of the day. The telegraph dominated the thinking of Frederic Myers with his theory of “telepathy” in the last two decades of the 19th Century. In the Rhines’ day, radio was an obvious metaphor for ESP. And later remote-viewing researchers naturally likened the practice to tuning in on a TV signal. Today, the metaphors of nonlocality and entanglement between psychics’ minds and the wider universe are hot. But if “psi” is really precognition, then nothing necessarily needs to be sensed or detected from outside the body or even outside the nervous system. It would be the nervous system’s connection to itself across time that matters.

In that view, a soldier with Spidey sense might not actually be receiving some kind of waves coming from the IED down the left path and thus leading her squad down the right path. Her brain might instead be post-selecting on the ambivalent future reward of having taken the right path and then heard the explosion and screams of some other less-fortunate squad that took the left. Intuition would be a premonition of ambivalent future reward. If that’s the case, then the neurotransmitter dopamine and the reward circuits that use it might have a lot to do with this disturbing-yet-rewarding “signal” from the individual’s future.

This is why I was (selfishly) a bit excited to hear about Nolan’s and Green’s discovery. In interviews such as his recent appearance on Café Obscura, Nolan has highlighted the caudate and putamen’s role in intuition, but one way of looking at intuition is generating actions from available information quickly, bypassing conscious, deliberate decision-making. When we talk about bypassing those more deliberate processes, we’re essentially talking about making our responses automatic. In a lot of neuroscience literature, the dorsal striatum is not only associated with intuition but also with habits and compulsions—actions we don’t necessarily want to engage in but do so anyway, feeling we have no choice. In other words, in the brain, intuition is closely tied to habit and to the most un-“freely willed” of our behaviors, such as compulsions and addictions.

This is why I was (selfishly) a bit excited to hear about Nolan’s and Green’s discovery. In interviews such as his recent appearance on Café Obscura, Nolan has highlighted the caudate and putamen’s role in intuition, but one way of looking at intuition is generating actions from available information quickly, bypassing conscious, deliberate decision-making. When we talk about bypassing those more deliberate processes, we’re essentially talking about making our responses automatic. In a lot of neuroscience literature, the dorsal striatum is not only associated with intuition but also with habits and compulsions—actions we don’t necessarily want to engage in but do so anyway, feeling we have no choice. In other words, in the brain, intuition is closely tied to habit and to the most un-“freely willed” of our behaviors, such as compulsions and addictions.

Like other parts of the reward circuit, the cells of the dorsal striatum, including those spoke- or antenna-like connections identified by Nolan and Green, predominantly use dopamine for signaling. It is part of what I think of as the brain’s “jouissance system.” Jouissance is just a fancy French word for the drive that takes over in a compulsive disorder like a neurosis or an addiction—a reorientation of the salience of incentives away from some euphoric payoff or reward into various cues associated with it, which perpetuate the drive. Freud called it the “compulsion to repeat,” and for him it was the basis of neurotic behavior.*

If anomalous cognition or psi is “really” (or mainly) precognition, it makes sense that brain areas governing habit and compulsivity might figure prominently in its neurobiology. The reason is that computation across the fourth dimension depends on repetition: The brain’s ability to make some sense of information coming down the pike requires self-consistency over time. Just as a New Yorker will have an easier time understanding a time traveler from a 25th Century where they still speak recognizable English in New York versus a future where everyone had switched to Russian, the more we expect our reactions to stimuli in ten minutes or a year will be the same as now, the more decontextualized information coming from our future can make sense and be useful in guiding behavior. Compulsions and habits, which in many ways are just overlearned skills, create the necessary self-expectations that might serve as the cipher-key of information back-flowing from an individual’s future.

A “Predictor” circuit could in a sense be likened to an antenna, but in the fourth dimension. Just like some antennae appear as grids, parallel lines, or “repetitions” in space, a fourth-dimensional biological antenna would likely involve repetition of behaviors over time.

iPredictor™

Here is where we come back to the theme of “free will” and Ted Chiang’s story. Not unlike people in the grip of an addiction or a compulsion, intuitive and highly skilled people are those who readily make decisions without thinking. Their high performance, as well as their “psi,” is an outside-of-conscious-will phenomenon. And it may be the best model for thinking about the unconscious in relation to consciousness: The unconscious leads the way, but it may be in a necessary partnership with the 20-20 hindsight of conscious awareness. The squad leader’s psi/jouissance needs that confirmation in the form of the screams coming from the other path. The time-looping relation to future confirmation is crucial.

There is a tendency to think of precognition as some kind of superpower enabling the individual to scan various options ahead and select the optimal one, like a kind of radar. But if in fact precognition is just what Freud called “the unconscious” in many or all its manifestations, then we need to rethink its role in our lives. it is not, in that case, some “super” faculty giving us the ability to spot dangers and avoid them—which could lead to the paradoxical situation of preventing a foreseen outcome. It is instead the faculty that prepares us, cushions us, for alarming news and close calls that do lie ahead in our un-freely-willed future.

There is a tendency to think of precognition as some kind of superpower enabling the individual to scan various options ahead and select the optimal one, like a kind of radar. But if in fact precognition is just what Freud called “the unconscious” in many or all its manifestations, then we need to rethink its role in our lives. it is not, in that case, some “super” faculty giving us the ability to spot dangers and avoid them—which could lead to the paradoxical situation of preventing a foreseen outcome. It is instead the faculty that prepares us, cushions us, for alarming news and close calls that do lie ahead in our un-freely-willed future.

If there is something like a radar, it would really (in this view) be our ordinary conscious thought processes that consider counterfactual situations and scenarios and make us take wise precautions and adjust our behavior based on past errors. The anxious brain lying awake at 3AM consciously worrying about disasters and dangers and agonizing over mistakes is the real radar that steers us clear from undesirable outcomes ahead. However, in a block universe, action verbs like “steer” need to be seen more statically, as parts of four-D time loop formations. “Steering toward success” needs to be rephrased as “discovering you are the person who was successful.” Overhauling our language to deal with a block universe is a massive subject, for another post (or book).

But the bottom line is: I will be the first in line at the Apple store when the Chiang-inspired iPredictor goes on sale in May, 2026. Far from creating a population of akinetic mutists, it will act as a material(ized) koan, fast-tracking users to Satori.

Postscript: Failure Is Not an Option

People who find the idea of precognition, retrocausation, and time loops interesting are often of an occultist bent, and I have been asked several times how the block universe that allows precognition can be reconciled with the active intention setting that a magician might utilize. And what about the idea that thoughts and intentions create our reality? I often think of my friend Mitch Horowitz’s brilliant writings on New Thought (such as his recent book The Miracle Club), and how determinism in a block universe seems on the surface so antithetical to the outlook he describes: that thoughts are causative.

Sometimes when two ideas seem diametrically opposed, zooming in reveals a closer kinship. For one thing, I agree with Mitch’s basic assertion that thoughts are causative. Where I may differ is in the direction of their causation. If our unconscious behaviors are premonitory of what we think of as our will, if what we “precognize” with our bodies and our automatic (unconscious) actions is our future conscious thoughts, realizations, and “intentions,” then those thoughts are by definition retro-causing the past. Our conscious realizations and intentions for the future are actually writing (or “having written”) our past life scripts. They do this not just by reordering our memories in the present (Slavoj Žižek’s cautious, not-quite-retrocausal, not-quite-Gnostic position), but by actually directing our actions from the future and influencing our younger selves.

Sometimes when two ideas seem diametrically opposed, zooming in reveals a closer kinship. For one thing, I agree with Mitch’s basic assertion that thoughts are causative. Where I may differ is in the direction of their causation. If our unconscious behaviors are premonitory of what we think of as our will, if what we “precognize” with our bodies and our automatic (unconscious) actions is our future conscious thoughts, realizations, and “intentions,” then those thoughts are by definition retro-causing the past. Our conscious realizations and intentions for the future are actually writing (or “having written”) our past life scripts. They do this not just by reordering our memories in the present (Slavoj Žižek’s cautious, not-quite-retrocausal, not-quite-Gnostic position), but by actually directing our actions from the future and influencing our younger selves.

So in other words, I think our thoughts are efficacious, and specifically in our past—that is to say, in the past (or prehistory) of the thought. This kind of retrocausation may be operative on millisecond or second scales, such as in the presentiment research of Dean Radin or the “feeling the future” studies of Daryl Bem, but also over days, years, and decades. A macro model for this is dreams, of the sort I’ve discussed frequently on this blog. If a person’s day is even slightly affected by a dream (even just in the mere act of writing it down) and the dream consists of or contains precognitive material—which it’s even conceivable all dreams do—then information from the future has exerted a shaping force on the past … even if we misinterpret the dream. If this time-looping logic goes all the way down, even to the cellular level of thoughts in the brain, as I strongly suspect it will turn out to, then our thoughts are causative of our histories. We ongoingly shape ourselves into the past. Our past is an effect of our future.

Note that this is not the same thing as “changing the past”—the idea that we could somehow meddle in and alter our timelines—the Mandela effect and whatnot. How would we ever know our timeline had changed? We can however produce improved outcomes in our near future when we realize how we have contributed to shaping our past. We can sow seeds in the past for a better tomorrow. This is exactly the payoff of the “dream paleontology” I described a few posts back, and it will turn out to be the motto or philosophy of our timefaring descendents.

We need to remember: What we think we “know” of the past (or present) is at best a tapestry of suppositions, assumptions, and interpretations. Most modern conceptual frameworks for understanding the past make no room for a teleological influence and thus we think of the past as fixed and untouchable by any later influence … but that’s just a modern, post-Enlightenment failure of imagination, not a real limitation on reality. Increasingly, evidence shows our commonsense view of causality only going in a forward direction is simply wrong—in Time Loops I call it “folk causality.” We simply need to update our imaginations.

We have no proof yet, but my hunch is that the underlying principle in precognition will probably turn out to be retrocausal processes in quantum biology—perhaps quantum computation in molecular structures controlling brain plasticity (microtubules). One way we already know quantum processes manifest in biology is the phenomenon called quantum tunneling: the apparent fast-forwarding of unmeasured particles toward their destinations. (We know photosynthesis and enzymatic actions depend on it, for instance.) The retrocausal interpretation of quantum mechanics reframes this: It is the “measurement” (or just, terminal interaction) that retro-determines the particle’s path.

This quantum fast-forwarding toward what to our eyes appear like “intended” outcomes could be the X factor separating life from lifeless matter in organic molecules, the missing “vital” principle underlying life. It would force us to reincorporate “purpose and desire” into our understanding of living systems. And it would scale up in nervous systems, which tend (to some greater-than-chance degree) to post-select on survival and rewards in the organism’s future.

This allows us to “flip” the New Thought idea that success is built on mind. Mind is really built on success. Mind IS success. And since on a basic level that “success” is post-selecting the actions leading to it, there is no “other” world of “failure” (or “missing”) out there as an option for where a particle could go or what an organism could do. That Spidey-sense squad leader automatically took the right path without the IED, and there was no alternative or counterfactual reality where she took the left path instead. Failure is literally not an option in a retrocausal universe, at least on the most basic level of particles. The Mind scales up this “tunneling toward the optimum” principle and utilizes it to create the splendiferous 4-D formations that are our biographies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Many thanks to Kit Green and Garry Nolan for sharing their research and slides with me, and for answering my many questions. My interpretations of their finding are entirely my own. Thanks also to Michael Garfield of the Future Fossils podcast for alerting me to Chiang’s “What’s Expected of Us.”

NOTES

** A similar shift of orientation toward cues rather than payoffs also reflects the intrinsic reward that takes over in practioners of highly trained skills. For a race car driver, the pleasure is in the driving, not just in crossing the finish line—in fact, the latter is a bit of a disappointment, because it means the race is over. Presumably some of the intuitive high-performers in Nolan’s and Green’s sample are fueled by the same dopamine drive, a kind of jouissance from always being on the edge of peril or risk.

Eric, are you aware of a critique of your “Time Loops” book published on a “Psi Theory” blog?

https://psitheory.com/2019/01/06/time-loops-the-critical-notes/

Well, were you aware of it or before or not, now you certainly are… so maybe you can go there and write a reply? Would be intersting to see a debate.