The Biggest Bullshit: David Lynch and the Cowboy

Well, there are many kinds of films. Most of them, nowadays, don’t demand much thinking. That makes me very, very upset. It makes me upset that they think the audiences have grown unused to thinking and that they only want things spelled out for them, in a platter. That’s bullshit, and a big one. People love to think. We are all detectives. We love to observe, we love to deduce. It is great to pay attention. We have a lot of fun this way. — David Lynch, on Mulholland Drive

You’re not thinking. You’re too busy being a smart-aleck to be thinking.—The Cowboy, Mulholland Drive

Suffering comes from the energy we perpetually expend in keeping up appearances of knowing, the constant knowing attitude we take toward life. Been there, done that, same old same old. It becomes the armor we clothe ourselves with—projecting this image that I know who I am, and why I’m here, and what I’m doing. In the postmodern world, this attitude has become institutionalized in sarcasm, ironic detachment, snarky jadedness, and (to use the Cowboy’s anachronistic expression) being a smart-aleck.

How true, the words of the Cowboy: We go through our lives taking a too-cool-for-school, smart-alecky attitude toward the givens of our lives, and as a result, fail to think and pay attention.

The Zen masters tried to get their pupils to stop knowing, to un-know, and they had different ways of doing it. The Soto school made the monks just sit, stop imagining they had anything more important to do or anyplace better to be. It’s much tougher than it sounds. It appealed (and still appeals) to students who naturally have calm, relaxed, patient minds. The Rinzai school, on the other hand, used story-puzzles, or koans, and appealed (and still appeals) to active intellects who naturally can’t resist interpreting and solving puzzles. Koans invite intellectual analysis, but at a certain point—weeks or months later—the intellect runs aground, and suddenly the monk finds himself or herself in a transfigured place.

“Rinzai” is how the Japanese pronounce the name of the 9th-Century Chinese master Lin-Chi. David Lynch says of his film Mulholland Drive that “We are all detectives. We love to observe, we love to deduce.” He understands people’s love of interpretation, of playing detective, and I would bet money he created Mulholland Drive as a deliberate koan. If meditated upon at sufficient length, it can take you to a place beyond interpretation. But we have to go through that effort of intellectual interpretation in order to awaken, to transcend. When we do that, we find ourselves not in a meaningless depressing world but in an enlarged, more immense, more spacious place that is full of possibility and importance and power.

I wrote in another post that Mulholland Drive specifically lures you to distinguish the “dream part” from the “real part” of the main character Diane’s (Naomi Watts’) story. Innumerable clues are there to indicate that the first two-thirds of the film, right up until the Cowboy’s “Hey pretty girl, time to wake up,” are meant to be seen as a textbook wish-fulfillment dream sequence that scrambles, rearranges, and transforms all the elements of Diane’s depressing “real-life” predicament—that she has hired a hit-man to kill her glamorous actress lover Camilla (the amnesic dark-haired “Rita” in the dream) after the humiliation and heartbreak of the latter’s rejection of her and announced engagement with a famous film director, Adam Kesher.

After a couple viewings of Mulholland Drive, this interpretation emerges pretty clearly and naturally. The film has thus been compared to The Wizard of Oz: The long dream core of the film consists of elements from the main character’s real life but jumbled and transformed according to dream logic, to create a fantasy that removes all the pains of the dreamer’s existence, erasing all of her guilt, and giving her all the things she wishes for. Textbook Freud.

Almost.

Once you’ve performed this “natural” interpretive procedure that the film invites, and followed it to its conclusion, you discover that you’ve been led into a trap: When you put the final piece in place, the film shows a message that was not visible before. This is the real genius of a film that is already genius on every more superficial level.

The key to the hidden message is the Cowboy.

The first time we (the audience) see the Cowboy is when he berates Adam Kesher for being a smart-aleck and for thinking he can have any woman he wants as the lead in the film he is making. He also says “You’ll see me once more if you do good, twice if you do bad.” Although it is addressed to the buffoonish Kesher, we likely take this promise as meant for “Betty,” the “real world” Diane, whose story this all really seems to be.

But … if we follow Diane’s “real” chronology as reconstructed in the aforementioned Wizard of Oz interpretation, this dream appearance is actually the second time Diane sees him—the first having been when he briefly walks through the room at the party where Adam and Camilla (dream Rita) announce their engagement. Diane’s dream has transformed this single fleeting “day residue” into one of two central psychopomps in the film (the other being the Club Silencio emcee), and her unconscious creates the dream of the Cowboy chastising and threatening Kesher that he’ll appear twice more if he does bad. This means Diane, the “real” subject of the movie, encounters the Cowboy only once more after this warning before she dies: When he appears at the end of her dream, in her doorway, and tells her it’s time to wake up.

We could interpret this as indicating that Diane has done well … done well, perhaps, by killing herself—after all, her life has become untenable, as she has had her former lover killed and the detectives know, and are knocking on her door. There is no other way out for her but to blow her brains out.

But let’s face it: If it isn’t Diane who’s being bad, then it is us, the viewers, who are being bad, since we do see the Cowboy two more times after his first appearance at the Corral.

Gulp. What did we do wrong? How are we being bad?

The Cowboy has already told us plainly: By being smart-alecks. Smart alecks don’t think they need to pay attention and think about what’s being said to them, because they think they already know, already have things figured out. But of all films, Mulholland Drive is designed as a big demonstration that no, we (we audience members, we human beings) do not have it figured out, and we are in fact very poor learners.

Lynch has said that one of his earliest films, a short called Alphabet, was about the “anxiety of learning.” This theme is clearly alive and well in Lynch’s late works too: Like the characters in his films, we are made to feel dumb by what he shows us. The Club Silencio emcee assures us that there’s no band, that it’s all a recording, and yet we are surprised when a trumpet player stops fingering his instrument and the music continues. And just minutes later, as Rebekah Del Rio sings “Crying,” we are just as amazed when she collapses on stage and her recorded voice continues to sing as we were when the trumpet player stopped playing.

So the Cowboy and the emcee at Club Silencio are both stand-ins for Lynch the Master, Lynch the teacher, who like his close namesake Lin-Chi famously just barked at or struck his pupils get them to see the light.

In Mulholland Drive, we are being shouted at by a teacher whose impatience is, despite his ferocity, infinitely compassionate. This is because his works have a real-world purpose. They are initiations: He is trying to transmit a bit of learning that has been important to him and that he really wants to share with us. We won’t get it as long as we are being smart-alecks, so he is in effect slapping us in the face to get us to stop that behavior long enough to see what he is talking about.

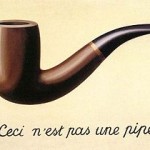

I explained in my earlier post that what he’s trying to get us to see is that there’s no “real” and no “not real” in the film—they are fundamentally the same, just following different narrative rules, just shot in different styles, to lead us into the trap of picking them apart and distinguishing them. It’s like Lynch has taken us on this long, very enjoyable journey, getting us to play detectives (who are, as we speak, knocking loudly on the door), only to lead us to a back alley where we are shown Rene Magritte’s painting The Treason of Images—with a picture of a pipe on a school blackboard and the caption “This is not a pipe”: There’s no “dream” and no “reality” in Mulholland Drive—it’s a movie, stupid. All parts are equally fictional; nothing is more real than anything else. It’s all equally unreal. It’s all a recording.

I explained in my earlier post that what he’s trying to get us to see is that there’s no “real” and no “not real” in the film—they are fundamentally the same, just following different narrative rules, just shot in different styles, to lead us into the trap of picking them apart and distinguishing them. It’s like Lynch has taken us on this long, very enjoyable journey, getting us to play detectives (who are, as we speak, knocking loudly on the door), only to lead us to a back alley where we are shown Rene Magritte’s painting The Treason of Images—with a picture of a pipe on a school blackboard and the caption “This is not a pipe”: There’s no “dream” and no “reality” in Mulholland Drive—it’s a movie, stupid. All parts are equally fictional; nothing is more real than anything else. It’s all equally unreal. It’s all a recording.

If we need confirmation, only note the absence of a “real world” counterpart of the mysterious blue box. It is opened in the “dream” by the strange blue key. A mundane version of the blue key is conspicuous in depressed Diane’s apartment at the end, and in a flashback, it is shown to her by the hit man in Winky’s diner, who says she’ll find it “at the place I said” when he has finished his job of offing her lover Camilla (dream Rita). Diane asks, naively, “What does it open?” The hit man gets a quizzical look and just laughs and shrugs at her dumb literal-mindedness: The point is, the key is a message, not actually a functional key that opens anything. There’s no “real” box … just like there’s no band.

A teacher of Tibetan dream yoga, Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche, writes that “ultimately the meaning in the dream is not important. It is best not to regard the dream as correspondence from another entity to you, not even from another part of you that you do not know. … It may sound strange, but this idea of meaning must be abandoned before the mind can find complete liberation. … Instead penetrate to what is below meaning, the pure base of experience.”

I don’t know if Lynch has ever said it explicitly, but I suspect he would say it, so I’ll venture: Movies, like dreams, can seduce and delight us with their obvious and hidden meanings, but ultimately they should take us to a place beyond meaning. Have fun decoding them, but don’t think that’s enough, that it is just about proving your cleverness; learn to see through the movie to the Real. Lynch’s later movies invite us to interpret and find meaning, but they are koans—traps meant to take us to a higher place. Mulholland Drive is his most exquisitely designed trap.

***

wonderful! is “the place beyond the meaning”, re interpetations of our synchronicities, the epistemic structure of synchronicity, i.e. the precognitive feedback loop? i.e. we properly or deeply interpret our synchronicity by coming to something like your theory of them?

on the other hand, i wonder if the Cowboy’s warning to Smart Alecks applies most to reductive interpretations of mysteries. . . which i myself am prone to btw. i’ve come to your blog via Erik Davis, and am challenged by your theory. am half-convinced already, in my half-comprehension. i resist because there many synchs in my personal xp that collate so many elements into a super-Shakespearian wit, and by co-opting my environment into graphemes or phonemes so that the most parismonious explanation of those experiences, for me, seems to be a Turing-Test-passing Intelligence communicating with me. and the “synch” initiates a Dialogue. and the Dialogue establishes an ethical pressure on my interpretation: don’t be rude to my Interlocutor by reducing him to e.g. feedback loops of my own precognition of mundanities.

yet when i think of the array of synch xps, my sense is that many of them can be explained by your feedback theory. your theory, then, becomes an important sorting tool, along with knowledge of Selection biases, Innumeracy, et cet – it helps me filter the noise from the Signal.