To the Unified Field (via Twin Peaks): David Lynch’s Paintings

“We live in a world of opposites, of extreme evil and violence opposed to goodness and peace. It’s that way here for a reason but we have a hard time grasping what the reason is. In struggling to understand the reason, we learn about balance and there’s a mysterious door right at that balance point. We can go through that door anytime we get it together.” —David Lynch

Many fans of David Lynch’s films are probably aware that he started as a painter and has continued to work in that medium all his life. (For example, they may have glimpsed him at work in his atelier in the documentary that accompanies the Inland Empire DVD.) But it has been frustrating trying to find examples of his paintings and drawings because there has been no single book comprehensively showcasing them. Finally, David Lynch: The Unified Field, the catalogue of an exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he studied as a young man, beautifully displays this “other” side of Lynch’s creativity.

It’s a gorgeous book, with an excellent long essay by Robert Cozzolino. It will do much to help Lynch claim the recognition he deserves as a very serious and original artist in a completely different medium from his film and TV work. I’ve spent days thumbing through it already and it is still full of delights and surprises.

It’s a gorgeous book, with an excellent long essay by Robert Cozzolino. It will do much to help Lynch claim the recognition he deserves as a very serious and original artist in a completely different medium from his film and TV work. I’ve spent days thumbing through it already and it is still full of delights and surprises.

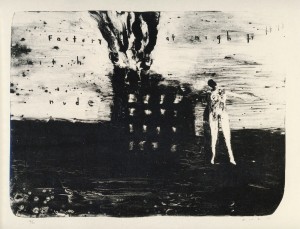

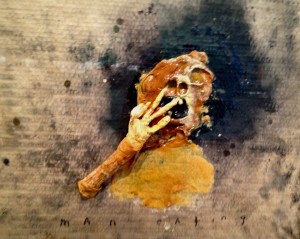

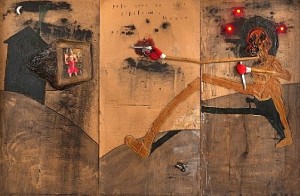

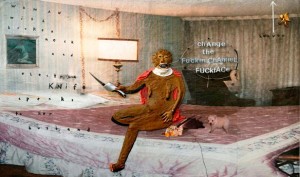

Lynch’s paintings, which are bold, childlike and threatening, remind me of Francis Bacon crossed with a dark Cy Twombly, often integrating thickly spackled paint (he mentions feeling the urge to chew on his paintings) with text that is either ultra-banal or psychotic. They reflect many of the same themes that recur in his movies, such as the violence, madness, perverse sexuality, and even paranormal phenomena that can be found when you peel back the surface of outwardly bland American life—or, that become visible at a smaller scale, when you zoom in. But—and this is crucial—they are also often funny; there is typically a sly poke in the ribs underneath the overt threat. (This is what sets him far apart from Bacon, say.)

Lynch’s early “moving picture” installation, “Six Men Getting Sick” (which has been recreated for the PAFA exhibition), is like a prototype for many of his later works both in film and on canvas. Six faces imprisoned in a gray-white wall vomit repeatedly; they cannot leave the wall, cannot get up and go to the doctor or even to the toilet, but are trapped in a perpetual materialist hell, purging throughout eternity. It somewhat reminds me of HR Giger’s transhumanist visions of immobilized sentiences trapped and suffering in and from brute matter, although Lynch’s outwardly “ugly” spectacle is far more ambiguous and strange than Giger’s sleek, seductive machine-erotic futurescapes.

Lynch’s early “moving picture” installation, “Six Men Getting Sick” (which has been recreated for the PAFA exhibition), is like a prototype for many of his later works both in film and on canvas. Six faces imprisoned in a gray-white wall vomit repeatedly; they cannot leave the wall, cannot get up and go to the doctor or even to the toilet, but are trapped in a perpetual materialist hell, purging throughout eternity. It somewhat reminds me of HR Giger’s transhumanist visions of immobilized sentiences trapped and suffering in and from brute matter, although Lynch’s outwardly “ugly” spectacle is far more ambiguous and strange than Giger’s sleek, seductive machine-erotic futurescapes.

On one level, Lynch could be called a painter of matter—of vomit, dirt, muck, rust, and biological decay that step in to co-create the world after humans have contributed their part. He is quoted in the opening essay about being allowed to spend time with corpses in the Philadelphia morgue when he was in art school, and the beauty he finds in “organic processes” that he got from his time spent with his father, who was a specialist in tree diseases working for the Forest Service when he was a child in Montana. Throughout his works, abandoned factories, mud and sores, or the brown stains on the made world, all become sublime.

But the matter, even when or especially when it is decaying and messy, is only barely covering over something deeper (or higher). In interviews (and in his brief 2007 book Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity

But the matter, even when or especially when it is decaying and messy, is only barely covering over something deeper (or higher). In interviews (and in his brief 2007 book Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity), Lynch always takes the opportunity to tell people how his own youthful anger and neurosis were cured through Transcendental Meditation and that his creativity is fueled by his twice-daily practice of dipping into the fundamental wellspring he calls the “unified field.” He would thus surely not mind us using his paintings for meditation or as advertisements for the rewards of meditation. Specific altered states of perception I have experienced as a byproduct of my own Zen-influence practice help me pin down exactly what the mysterious X quality in his paintings is—the precise tension they invoke (at least in me).

Buddhist writers don’t like to dwell on the mild altered states produced by meditation, preferring that we not get attached to them, but when you detach from your environment even for very brief periods, the world can afterwards take on a funny, mysterious, alive-yet-dead quality that is full of exciting unseen potential. I have noticed for years that after meditating, the world has an altered character that feels distinctly “Lynchian”: Specifically, it feels like the world has suddenly become the world of Twin Peaks—the ordinary, mundane world, but with something added that is a mix of mysterious, humorous, ominous, and subtly exciting. This is why I was so excited to finally get a book of Lynch’s paintings—to see if they had this same quality. I was not disappointed.

One way to think of the subtly altered state of perception I’m referring to is in terms of the “imaginal” that was described by Sufi scholar Henri Corbin: a kind of transfigured surreality overlaid on or coexisting with the everyday world, shimmering in and out of existence. Objects shine funny, oddly, significantly. They wink, ever so slightly. The importance of everything, even just this ashtray or coffee table or lamp, is ever so slightly elevated because through some subtle alteration of frequency, some slight turn of the dial, the shitty bathroom or grocery store or parking lot you happen to be standing in has suddenly become the VIP section of an international spirit-world airport, where one just might encounter other enlightened beings passing through. Even pieces of garbage or dead leaves are “slightly enlightened” celebrities, and you belong in their exciting world.

I think of this imaginal as a dangerous-feeling and uncomfortable perimeter or no-man’s land that surrounds the blissful Void or Absolute (or “unified field”) that all forms of meditation and mysticism aim for. The ultimate aim is not to linger in this perimeter zone, but you do need to pass through it—and the passage can be really enjoyable and interesting in its own right. This book of paintings confirms for me that Lynch, through his meditation practice, knows about this imaginal no-man’s land and that this is specifically what he is trying to show to us (because the unified field itself can’t be shown). Anything can happen, is about to happen, in this zone, and it pays to be fully awake and alert to the enhanced potential even in the most inanimate of objects and phenomena in it.

I think of this imaginal as a dangerous-feeling and uncomfortable perimeter or no-man’s land that surrounds the blissful Void or Absolute (or “unified field”) that all forms of meditation and mysticism aim for. The ultimate aim is not to linger in this perimeter zone, but you do need to pass through it—and the passage can be really enjoyable and interesting in its own right. This book of paintings confirms for me that Lynch, through his meditation practice, knows about this imaginal no-man’s land and that this is specifically what he is trying to show to us (because the unified field itself can’t be shown). Anything can happen, is about to happen, in this zone, and it pays to be fully awake and alert to the enhanced potential even in the most inanimate of objects and phenomena in it.

This imaginal is also a feeling of the world being like a veil. I don’t think it is accidental that Lynch’s film and TV work often includes drapery, most famously the “Black Lodge” of Twin Peaks, where strange shapes float behind red velvet curtains. However, what I actually think of more than drapes per se is the billowing dirty plastic covering the bare two-by-fours in the unfinished home where Shelly Johnson spoons baby food into the dribbling mouth of her ominously comatose husband Leo. If there’s any image from Lynch’s “moving picture” world that gives you a sense of what you’re in for with his paintings (such as the ominous triptych “Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House,” above), that would have to be it.

This imaginal is also a feeling of the world being like a veil. I don’t think it is accidental that Lynch’s film and TV work often includes drapery, most famously the “Black Lodge” of Twin Peaks, where strange shapes float behind red velvet curtains. However, what I actually think of more than drapes per se is the billowing dirty plastic covering the bare two-by-fours in the unfinished home where Shelly Johnson spoons baby food into the dribbling mouth of her ominously comatose husband Leo. If there’s any image from Lynch’s “moving picture” world that gives you a sense of what you’re in for with his paintings (such as the ominous triptych “Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House,” above), that would have to be it.

The apparent danger and craziness is not as real as it first appears; it has more to do with our own attitude. Even or especially in his most violent, threatening images, such as “Change the Fuckin Channel Fuckface” (below), or “I Burn Pinecone and Throw in Your House,” you can see Lynch standing back, with a slight mischievous twinkle in his eye, smiling, and you can see that he is actually smiling with you. He wants you to be pulled in, tripped up, as well as held at a slight distance, because this tension has something to teach us, and he wants to help us see it. He is inviting us to ride along with him in his buggy, on an interior journey that he sincerely believes can help everybody.

Getting past this imaginal, to the unified field, is not an intellectual exercise of decoding or interpreting hidden meanings: “It’s better not to know so much about what things mean or how they might be interpreted,” Lynch says. “Psychology destroys the mystery, this kind of magic quality. It can be reduced to certain neuroses or certain things, and since it is now named and defined, it’s lost its potential for a vast, infinite experience.” (Half a century ago, Rene Magritte said almost exactly the same thing, reacting against Freudians finding phallic symbols and such in his paintings: “Art, as I conceive it, is resistant to psychoanalysis. It evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist. … Nobody in his right mind believes that psychoanalysis could elucidate the mystery of the universe.”) Yet Lynch’s works bait such interpretation. This baiting and snatching away is part of the point, part of their “M.O.”—which is actually a very Rinzai Zen approach to enlightenment. As I’ve written previously about Mulholland Drive, you must go through the natural impulse to interpret Lynch’s work in order to finally break through the other side, into the irrational and transcendent.

Getting past this imaginal, to the unified field, is not an intellectual exercise of decoding or interpreting hidden meanings: “It’s better not to know so much about what things mean or how they might be interpreted,” Lynch says. “Psychology destroys the mystery, this kind of magic quality. It can be reduced to certain neuroses or certain things, and since it is now named and defined, it’s lost its potential for a vast, infinite experience.” (Half a century ago, Rene Magritte said almost exactly the same thing, reacting against Freudians finding phallic symbols and such in his paintings: “Art, as I conceive it, is resistant to psychoanalysis. It evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist. … Nobody in his right mind believes that psychoanalysis could elucidate the mystery of the universe.”) Yet Lynch’s works bait such interpretation. This baiting and snatching away is part of the point, part of their “M.O.”—which is actually a very Rinzai Zen approach to enlightenment. As I’ve written previously about Mulholland Drive, you must go through the natural impulse to interpret Lynch’s work in order to finally break through the other side, into the irrational and transcendent.

There’s nothing “preachy” about Lynch’s paintings, any more than there is in his movies, but the spiritual message is definitely there if you look for it. One of my favorite pieces in the book is “Holding onto the Relative (with One Eye on Heaven)” (at the top of this post) showing one of his typical disturbing/monstrous brown figures with elongated arms clinging desperately to the pulsating red heart of matter while looking toward the sun and screaming. Lynch’s philosophy I think is made pretty plain here: The frightening dimension is not simply the way things are, but the way we make them because we are afraid of letting go, or are holding on too tightly. Stretched-out arms and “reaching” (as well as arms/hands that are diseased) recur again and again in Lynch’s images, and I think it relates to this idea, and to the opposing forces that we cling to and that threaten to pull us apart.

Hi Eric,

Just found your work via The Anomalist, and it resonates with my last 5 years of investigating and experiencing this trickster stuff. So much more fun than being the progressive liberal agnostic I was before. Science has it’s limits as a tool for truth seekers, and so much of it is really just propaganda from the hidden ruling class. IMHO.

The David Lynch quote is my new favorite for the moment. Says it all, so well.

After casting a wide net into this new area of research for me, I have pulled up a few keepers. An example is the work of John Lamb Lash, particularly his book Not In HIs Image. Have you checked him out?

Happy truth seeking,