Altered States of Reading (Part 3): A Private Part of Time’s Anatomy

A couple weeks ago, Twitter etc. went wild when a new book revealed allegations that UK Prime Minister David Cameron had, during an initiation ritual while at Oxford, inserted “a private part of his anatomy” in the mouth of a dead pig. To an entire nation, it was a hilariously obvious permutation of Charlie Brooker’s disturbing debut episode of his Black Mirror series four years earlier, which centered on a British Prime Minister being blackmailed to have sex with a pig on live television, focusing specifically on the role of social media in compelling the leader to carry out the deed.

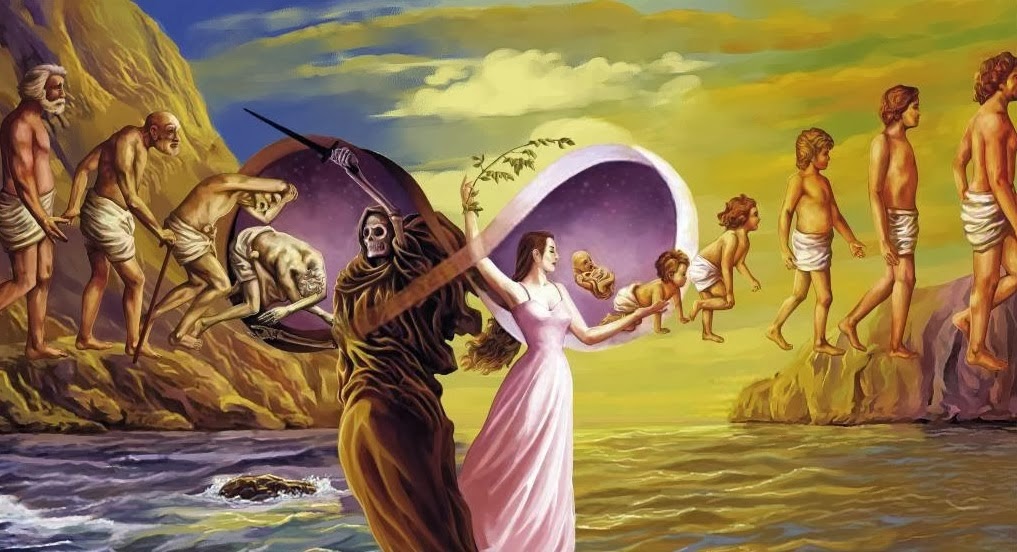

Fear of foresight causes all but the boldest writers to misinterpret their own visionary creative states as pointing to the past (i.e., channeling a muse or spirit, or maybe a past life) instead of what they really are: actually pulling information from their own future timelines.

This kind of thing—not the pig part, but “low culture” (e.g., TV, pulp) writers predicting the future, including future revelations of events that occurred in the past but of which the writer could have had no knowledge—happens all the time. Yet our collective disbelief in anything like precognition causes us to simply have a curious chuckle at these coincidences … maybe be a little “weirded out” (as Brooker said he was) … and then forget them soon afterward. It doesn’t occur to anyone to actually keep a tally. Nevertheless, I feel confident that enterprising grad students in some future department of Precognitive Media Studies will one day go back and scrutinize the whole archive of network TV from its inception, comparing dates teleplays were written with subsequent news headlines, and will turn up some pretty mind-blowing correlations.

In part one of this series, I described such a possibly prescient relationship between the planetary computer Vaal in a 1967 Star Trek episode called “The Apple,” written by science fiction writer Max Ehrlich, and Philip K Dick’s VALIS over a decade later. For various reasons, I suggested this may have been an inadvertent precognitive “plagiarism from the future” on Ehrlich’s part instead of, or in addition to, the usual forward-in-time influence of Ehrlich’s Star Trek episode on Dick’s novel.

Delving into the matter, I found that Ehrlich had not only seemingly anticipated other of Dick’s themes (and book covers), but also seems to have shared Dick’s interest in the paranormal sources of people’s dreams and obsessions. I don’t know much about Ehrlich’s life, but when writers take an interest in such things, it often arises from personal experience or at least some hunch that they themselves are in contact with sources of information that go against the prevailing mechanistic, materialistic worldview (i.e., the creative pattern Jeffrey Kripal described at length in Mutants and Mystics).

Boring Old Reincarnation

“I’ve always wondered why people have always reincarnated from the past. Those few times when I’ve had feelings of remembering another life, it was from the future.” Jacques Vallee

Ehrlich was specifically interested in reincarnation. He is most famous for his 1973 novel (turned into a 1975 movie) The Reincarnation of Peter Proud, about a young professor inexplicably obsessed with Indians and increasingly troubled by recurring dreams of living another life and being murdered by his wife while taking a swim in a lake. Proud accidentally discovers the real setting of his dreams in a TV broadcast (a motif Ehrlich no doubt precognitively borrowed from Spielberg’s Close Encounters a couple years later); urged by a parapsychologist interested in reincarnation, he travels to the New England town in the TV program to investigate his nightmares and confirm his growing belief that they are indeed memories of a past life in which he was murdered.

Ehrlich was specifically interested in reincarnation. He is most famous for his 1973 novel (turned into a 1975 movie) The Reincarnation of Peter Proud, about a young professor inexplicably obsessed with Indians and increasingly troubled by recurring dreams of living another life and being murdered by his wife while taking a swim in a lake. Proud accidentally discovers the real setting of his dreams in a TV broadcast (a motif Ehrlich no doubt precognitively borrowed from Spielberg’s Close Encounters a couple years later); urged by a parapsychologist interested in reincarnation, he travels to the New England town in the TV program to investigate his nightmares and confirm his growing belief that they are indeed memories of a past life in which he was murdered.

Proud meets and befriends a girl named Ann, the daughter of a man of Indian heritage named Jeff Chapin, who had drowned “accidentally” two weeks before he was born (and when Ann was three months old), and he clandestinely interviews Ann’s mother (and Jeff’s presumptive killer) Marcia. Marcia becomes suspicious of her daughter’s boyfriend’s uncanny similarity to her late husband, which reawakens her own guilty but also hate-filled memories of him; Jeff had drunkenly raped her on their final night together. When Peter then goes for a swim in the same lake … rather stupidly … Marcia takes a boat out and kills him—in other words, duplicating the murder of him when he was her husband, two and a half decades earlier.

It’s a very unsubtle novel, and totally predictable, but its obviousness is kind of what makes it interesting: If you squint, you can almost see it as a PhilDickian story but without Dick’s level of intellectual nuance. Dick grasped that anomalous cognition, what we assume are memories from the past, could just as easily be memories from the future. This inversion of common sense is precisely what made Dick Dick, and in fact we know from his Exegesis that he had read or seen Peter Proud and had exactly that impulse to revise its core idea: “Idea for To Scare the Dead. Dreams, but not about the past as are the dreams in Peter Proud; rather, they are like the dreams about the approaching Spaniards by the Aztecs—visions of the future.”

In other words, here, as in my suggested relationship of Vaal and VALIS, Ehrlich is clearly a lesser writer grappling with the same phenomena as Dick was (in this case, intimations of his own self haunting him from another time) but interpreting them in a less original, more culturally safe manner. Had Dick or someone with more of his sensibility rewritten Peter Proud, it would be far more interesting as well as parsimonious: We might notice how Proud’s nightmares were precognitive of a TV program, first of all, and perhaps how by automatically (mis)interpreting his visions of drowning as related to the past, Proud’s actions inadvertently elicit or fulfill precisely the tragedy he was actually foreseeing in the future; he’d be killed in order to cover up an old crime that his search had stumbled on.

In other words, here, as in my suggested relationship of Vaal and VALIS, Ehrlich is clearly a lesser writer grappling with the same phenomena as Dick was (in this case, intimations of his own self haunting him from another time) but interpreting them in a less original, more culturally safe manner. Had Dick or someone with more of his sensibility rewritten Peter Proud, it would be far more interesting as well as parsimonious: We might notice how Proud’s nightmares were precognitive of a TV program, first of all, and perhaps how by automatically (mis)interpreting his visions of drowning as related to the past, Proud’s actions inadvertently elicit or fulfill precisely the tragedy he was actually foreseeing in the future; he’d be killed in order to cover up an old crime that his search had stumbled on.

It would be, in other words, exactly like a cross between any number of Dick’s stories (like Minority Report) and Nicolas Roeg’s exquisite 1973 film Don’t Look Now—a tragedy unfolding directly from a skeptic misinterpreting a precognitive vision of his own funeral as a percept in the present.* Interestingly, Ehrlich later continued his reincarnation obsession with a 1979 novel, Reincarnation in Venice, which begins just like Roeg’s movie ends: with a murder on one of Venice’s canals.

Such a revision presents us, really, with the “unconscious” of Ehrlich’s novel. I’m not saying there was a psi connection in this case, but there is a curious coincidence of names again. What is a “Peter Proud,” after all, but an erection, a filled dick?** Even though his imagination was not up to Dick’s level and thus he wrote about boring old reincarnation instead of actually seeing the future, is it too much a stretch to suppose Ehrlich may have resonated with the time-looping themes Dick was exploring and perhaps with his name as well?

Such a revision presents us, really, with the “unconscious” of Ehrlich’s novel. I’m not saying there was a psi connection in this case, but there is a curious coincidence of names again. What is a “Peter Proud,” after all, but an erection, a filled dick?** Even though his imagination was not up to Dick’s level and thus he wrote about boring old reincarnation instead of actually seeing the future, is it too much a stretch to suppose Ehrlich may have resonated with the time-looping themes Dick was exploring and perhaps with his name as well?

Fear of Foresight

Like many (or all?) time travel narratives, Peter Proud is fundamentally an Oedipal story: The murder that ends the novel comes on the night Peter is expecting to sleep with, essentially, his own daughter Ann; the incestuous tension is not lost on Peter himself, although it doesn’t seem to give him too much pause. In psychoanalysis, the crime for the Oedipal transgression is castration … and what is killing a “Peter” but that?

It often serves our interests to think our fate is out of our hands, and thus any uncertainty about time and what it would mean to have authentic foresight confuses us and scares us.

As I suggested in my “Time’s Taboos” post, it is precisely Oedipus’s confused enjoyment, which “impossibly” connects his future and past, that turns psi into a psychoanalytic problem. The point of the tragedy is not merely that Oedipus committed an ancient version of the “grandfather paradox,” killing his father and marrying his mother; it is that he committed this crime and enjoyed it, and only belatedly discovered what it was that he had been enjoying. Oedipus is thus really a tragedy about disbelieved (and consequently misinterpreted) psi.

I am wondering whether we shouldn’t think of the idea of reincarnation as a kind of defense or denial of the Oedipal situation, a way for people to safely express their baffling precognitive or otherwise paranormal experiences without feeling like they’ve committing the ultimate taboo of ‘traveling’ mentally into the future. Such an idea would raise very interesting possibilities about much “survival” literature that go well beyond a single early 70s paranormal page-turner: What if people’s “past-life memories” are really precognitions of scenes of confirmation that elicit a reward—the reward of a parent, the reward of a researcher, their own reward in being something special? Is reincarnation just an Eastern way of pretending that the thin, gauzy veil of the future is actually a mirror?

Both Oedipus and the idea of haunting discarnate spirits were important themes in the life of probably the most famously prescient of writers, Morgan Robertson, the guy who prophesied the sinking of the Titanic 14 years before it occurred, as well as other events. True to the pattern, Robertson was not only a poor writer (unfortunately, in both senses), but he was also deeply interested in the psychic possibilities of the subconscious mind; he believed when he was writing that he was channeling “some discarnate soul, some spirit entity with literary ability, denied physical expression…” Intrigued by his prophetic gift and by the unfortunate circumstances of his sad life and career, the parapsychologist and psychiatrist Jule Eisenbud delved into Robertson’s stories and novels in search of clues to his character. His essay “Chance and Necessity: Is There a Merciful God in the House?” in his 1982 book Paranormal Foreknowledge is an utterly fascinating exercise in psi-criticism.

According to Eisenbud, who took the time to read an impressive chunk of Robertson’s pretty unreadable-sounding body of work, his hyper-masculine protagonists on the high seas invariably pine for mother figures they are fated never to possess, while they rail against the inscrutability of fate. The iceberg that sinks the “Titan” in Robertson’s most famous work Futility is just one example of cruel destiny that Robertson’s protagonists are unable to avoid, except occasionally in the depths of drink or, in a few very interesting cases, through an uncanny sixth sense. The protagonists are pretty clearly self-portraits.

According to Eisenbud, who took the time to read an impressive chunk of Robertson’s pretty unreadable-sounding body of work, his hyper-masculine protagonists on the high seas invariably pine for mother figures they are fated never to possess, while they rail against the inscrutability of fate. The iceberg that sinks the “Titan” in Robertson’s most famous work Futility is just one example of cruel destiny that Robertson’s protagonists are unable to avoid, except occasionally in the depths of drink or, in a few very interesting cases, through an uncanny sixth sense. The protagonists are pretty clearly self-portraits.

Several friends (writing in a 1915 volume called Morgan Robertson, The Man) confirmed the writer’s psychic gifts, although oddly enough, none of them ever mentioned his most uncanny prophecy about the Titanic, nowadays his only claim to fame. (Eisenbud assumes this lacuna is probably because such mention would have seemed in bad taste, just three years following the disaster.) Eisenbud links Robertson’s prophetic habit directly to his tortured obsession with destiny and the question of man’s ability to change it—a question seemingly tied to his drinking problem, the “iceberg” in his life that he couldn’t escape no matter how hard he tried. Very sadly, drink left him, in his early fifties, a destitute and forgotten failure in his own eyes. He died at age 54; he was found, oddly enough, standing up, leaning against a bureau in a hotel room.

Having observed precognitive and other psi phenomena throughout his clinical work, Eisenbud identified a specific pattern of individuals expressing precognitive ability as part of a gambit either to subvert apparent destiny or to camouflage themselves within it to allay their guilt. Eisenbud specifically compares Robertson to a married clergyman patient of his who produced uncanny precognitive dreams as part of a defense against his homosexuality. There are hints in Robertson’s stories too of an (at the time) unspeakable sexual orientation that may have driven him unconsciously to choose a life of the sea for several years but write of it as though it were a kind of grim fate he could not avoid: The world of his fiction is a sweaty fantasy of manly seamen pressed into service, constantly bloodying each other in brutal fistfights, etc. Robertson seemed to want fate to absolve him of something that he feared was a choice … and vice versa. His precognition, Eisenbud argues, answered this need.

Eisenbud makes a very key observation that goes well beyond Robertson in its implications: “With such an ambivalent attitude toward fate, all one would need, it might seem, would be heads and tails on the same throw. But any good precognitive event provides just this, since … the metaphysical significance of such an occurrence is sufficiently in question to satisfy both schools.” Had Robertson been born a few decades later, he might have fastened on Jung and the similarly ambivalent concept of synchronicity, to satisfy the same need. I’ve argued elsewhere that synchronicity is ultimately an empty concept, a kind of security blanket that absolves us of the responsibility to actually engage with our foresight and confront its implications. But some kind of security blanket about fate may be something we all need, in one way or another, because we are all at least a bit ambivalent about the whole question of fate.

While we might think we want to know the future, so we can change it, for example, most of the time we really do not want that responsibility. It often serves our interests to think our fate is out of our hands, and thus any uncertainty about time and what it would mean to have authentic foresight confuses us and scares us. Does seeing the future doom us or “lock it in” in some way? … Or does a vision of the future make it radically open to alteration and force us to take responsibility? Precognition is the ultimate can of worms that is best left unopened, which is why it is almost always only expressed unconsciously and inadvertently, either in the course of skilled activities where we are blind to it, or occasionally as parapraxes or creative inspirations whose source we misidentify and whose true prescience largely eludes us.

Fear of foresight thus causes all but the boldest writers to misinterpret their own visionary creative states as pointing to the past (i.e., channeling a muse or spirit, or maybe a past life) instead of what they really are: actually pulling information from their own future timelines. Dick, almost alone among genre writers, was not afraid of the latter possibility.

Is a Cigar Ever Just a Cigar?

Despite the various cultural and psychological forces acting to divert our attention from psi, I anticipate that in our lifetimes, we will see it acknowledged, specifically as precognition, facilitated by the discovery that the brain is a quantum computer continually accessing information in its own future as well “repressing” unwanted data into its own past. The physics of information that Jacques Vallee called for, governing our weird relation to time, will turn out to be none other than the hyper-associative logic of the personal unconscious and memory, just as it is formed and revealed in dreaming, the nightly updating of the search system we use to find and index this atemporal data. Dreams are not “wish fulfillments” as Freud thought, but Freud was exactly right in identifying their utterly associative, illogical character; although I don’t think he saw the link with Freud, Vallee called it a “metalogic,” which is a good term.

In the future, Christ on the Cross may be replaced by the 53-year-old Dick sprawled unconscious on the floor next to his coffee table, a martyr to the new religion of psi.

In the metalogic of our brain’s mostly unconscious search system, puns (both verbal and visual) are probably the most characteristic form of coincidence, forming the nuclei of attractor phenomena in the symptom space of psi. This is not the Jungian world of noble and poetic archetypes, but a cringingly personal world of low humor and wordplay. In such a world, there’s a lot in a name … particularly one as suggestive as Phil Dick’s.

I don’t know if I’m the first to suggest this, but I think Dick occupies a unique, special place at the juncture between the linear-causal classical worldview and the psi-dominated landscape of the future in part because of the accident of his name. The associative networks in the brains of readers (and in his own brain) unconsciously will have made a special place for him because his name happens to be that of the Phallus. In Lacanian theory, the Phallus is the virtual/absent emblem of the Real, the black hole around which the whole symbolic order revolves, producing in its vicinity all the apparent and actual time distortions that black holes in space can generate. The Phallus is the empty signifier that radically warps the spacetime of jouissance.

In other words, Dick was a living pun, and he acted and increasingly acts in our culture as a symbolic-associative attractor: His influence continues to grow posthumously, and it may even be that history converges more and more on his writings, increasing their prophecy quotient, precisely because of this associative attracting power. It is Dick’s prophetic-ness that made him famous, and it is his fame that made him prophetic, in a feedback-loop. Genius, I am convinced, is nothing other than prophecy, the ability to strongly channel one’s own future.

In other words, Dick was a living pun, and he acted and increasingly acts in our culture as a symbolic-associative attractor: His influence continues to grow posthumously, and it may even be that history converges more and more on his writings, increasing their prophecy quotient, precisely because of this associative attracting power. It is Dick’s prophetic-ness that made him famous, and it is his fame that made him prophetic, in a feedback-loop. Genius, I am convinced, is nothing other than prophecy, the ability to strongly channel one’s own future.

This kind of Bohmian resonance is responsible for the very shape of culture, I think: a kind of “cellular” relationship between precognition and confirmation (or the Not Yet and the Actual). This cellular structure happens to be most visibly apparent when psi leaves a rich paper trail, as it does with frenetic, amphetamine-fueled (or alcohol-fueled, in Robertson’s case) genre writers. Occasionally their more respected “literary” cousins also tap into it, as Thomas Pynchon did when he made a “precognitive dick” the MacGuffin in his highly prescient (prescient about prescience) Gravity’s Rainbow. Because most of us mortals cannot accept or even imagine that we are ever seeing the future, however, we contort all our anomalous experiences to conform to commonsense linear causality, and our confusion results in various anomalous events that we generally manage to forget as soon as they happen.

Dick saw through culture’s psi-distorting linear-causal mystification; and it is significant that, not unlike “Peter Proud” in the above retelling, Dick’s untimely demise was a punishment for his offense, which (not unlike Oedipus) was a kind of self-enjoyment, prophetic jouissance.*** In the future, Christ on the Cross may be replaced by the 53-year-old Dick sprawled unconscious on the floor next to his coffee table—an image Dick himself foresaw. His untimely, confusedly foreseen death was a kind of martyrdom, fulfilling his destiny to be the absent signifier, the ultimate “vanishing mediator” preparing the way for a new religion of psi.

NOTES

* Nic Roeg is another rare artist of the period, besides Dick, who really confronted the issue of misrecognized precognition and overlapping time. It is present also in The Man Who Fell to Earth, a film that strongly influenced Dick’s VALIS but may have been influenced by VALIS in turn, precognitively: How else to explain the “alien” Thomas Jerome Newton’s brief vision of the pioneer family and their simultaneous, UFO-like vision of him—which is exactly like Dick’s/Horselover Fat’s superimposed ancient Rome, not to mention Dick’s own experiences of remembering seeing his future self visit himself in dreams. Roeg is subtly suggesting here that Newton is not actually a space traveler from another planet (the mundane, “nuts and bolts” assumption of the Walter Tevis novel the movie is based on) but is actually a time traveler from Earth’s thirsty, desiccated future. The story thus becomes one of Oedipal nostalgia—retreating into the past and staying there, descending into alcoholism, instead of going back to the future, where he came from. Alcohol (a stand-in for the breast) and Oedipus are a common convergence. It is also notable that Newton has no genitalia.

** Whether influenced in any way by Dick, Ehrlich was clearly highly conscious of his naming of his protagonist Peter Proud: The obscenely engorged member of Jeff Chapin before the rape is a vision that his widow cannot clear from her mind. The young Peter is like her own guilt as well as her own enjoyment come back to haunt her, the return of her repressed; Ehrlich makes it clear that Marcia’s guilt is as much over having enjoyed the rape as over the murder itself. Basically, Ehrlich whacks you over the head with the fact that Peter is a phallic symbol.

*** We usually say the punishment fits the crime, but in a Dickian universe the crime also fits the punishment: Dick died from multiple strokes; in other words, castration as punishment for masturbation. Don’t laugh—it could happen to you.

The relationship between past and future in precognitive events is a curious one. The most clearly precognitive dream I ever had seemed at the time to be an expansion on sometime that had happened a few years earlier, when my husband and I went to a concert with a couple we were friendly with at the time. The actual event five years later involved going to the zoo with a different couple we hadn’t yet met at the time of the dream but who were similar in a number of ways to the people in the dream.

I suspect that the dreaming mind tends to fill in the blanks with familiar figures and past events. And the one episode in the dream that was fuzziest and least visual — I noted down in the dream diary I was keeping at the time that we “seemed to be” in a van with five or six other people — was also the most unlike anything the the past and the closest to the actual later event.

Two other points. One is that even though the trip to the zoo was fairly trivial in itself, we were accompanied by our friend’s cousin, who had recently hurt her back and was in a good deal of pain (and possibly also on painkillers), and that cast a strange and tightly-wound mood over the day. The other is that in the dream it was colder out than we’d expected and I felt chilly. But in the real event, for no particular reason, I decided to bring along both a jacket and a sweater, telling myself that would give me a choice of which to wear — and when the promised sunshine never materialized, I wore them both and was glad to have them.

So perhaps precognition does allow us to change the future — only not consciously and not in any way we might expect.