The Rashomon Brain: Hunting Duck/Rabbits, Seeing Multiple Realities

“A man walks along the beach and unfortunately gets hit in the head by a coconut. His head unfortunately cracks open in two halves. Then his wife comes along the beach singing a song and sees the 2 halves and recognizes them and picks them up. She gets very sad of course and cries heart breakingly. That is exactly where I am tired of poetry. Supposing the lady just picks up the 2 halves and shouts into them very angrily ‘Stop that!’” — J.D. Salinger, “Teddy”

The latest thing in Quantum physics, it seems, is the “Rashomon Effect”: Observers create reality, so there may be as many realities as there are observers. This relates to what I was getting at in previous posts, riffing on themes in Philip K Dick’s Exegesis: Reality is multiple and shifting. There’s no single “glass football” cosmic history but infinite variations on the theme.

Beyond the reality of multiple observers, the more troubling state of affairs is that even individual observers are “multiple” in several fundamental ways. There is firstly the notion that even on a subatomic level the particles in our bodies are in disgreement as to what is real, because of light’s (and thus causality’s) finite speed limit.

But there is also the simple fact that our information about the world comes via multiple sensory channels and is processed in multiple ways in our brains. The basic fact that we see with two eyes, which gives us our 3-D picture of the world, means that even the two brain hemispheres must be regarded as separate observers of reality, having distinct interpretations and (one might suppose) “collapsing different wave functions.” The plurality of the psyche and the fact that the brain produces multiple separate representations, most notably within separate hemispheres that only imperfectly communicate with each other, produces something like a personal Rashomon Effect.

But there is also the simple fact that our information about the world comes via multiple sensory channels and is processed in multiple ways in our brains. The basic fact that we see with two eyes, which gives us our 3-D picture of the world, means that even the two brain hemispheres must be regarded as separate observers of reality, having distinct interpretations and (one might suppose) “collapsing different wave functions.” The plurality of the psyche and the fact that the brain produces multiple separate representations, most notably within separate hemispheres that only imperfectly communicate with each other, produces something like a personal Rashomon Effect.

Our brains juggle multiple realities, quite literally.

Fun With Dick and Jaynes

Dick wrote in his Exegesis that in the months prior to February 1974, when his mystical experience began, he had been taking megadoses of B and C vitamins according to a regimen he had read about in Psychology Today, an experimental treatment for schizophrenics designed to increase communication between the brain hemispheres. There is no way of knowing if this had anything to do with his altered perceptions, hypnagogic voices and imagery, and amazing synchronicities over the ensuing months, but among the sources that eventually gave him insight on his experience were books on the emerging science of brain hemisphericity, including Julian Jaynes’ pathbreaking 1976 work The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. When Dick read a Time magazine article about Jaynes’ work in 1977, it seemed almost a perfectly timed answer to some of his most pressing questions, and indeed he felt that the theory confirmed conclusions he had arrived at based on his own experience.

Jaynes’ book merged the then-new understanding of the separate functioning of the two brain hemispheres with the study of ancient cultures. Specifically, Jaynes argued that ancient humans always heard divine voices in their heads because their hemispheres did not intercommunicate to the degree that moderns’ brains do; thus voices from one hemisphere would be heard by the other as coming from outside—interpreted as spirits or gods. In the works of Homer, for instance, there is no evidence of characters possessing what we would call an inner life—they obey the dictates of divine commands.

Jaynes’ book merged the then-new understanding of the separate functioning of the two brain hemispheres with the study of ancient cultures. Specifically, Jaynes argued that ancient humans always heard divine voices in their heads because their hemispheres did not intercommunicate to the degree that moderns’ brains do; thus voices from one hemisphere would be heard by the other as coming from outside—interpreted as spirits or gods. In the works of Homer, for instance, there is no evidence of characters possessing what we would call an inner life—they obey the dictates of divine commands.

According to Jaynes’ interpretation, a major shift in consciousness occurred around 1250 BC, enabling the hemispheres to act with greater unity, and since then humans have no longer heard the voice of the divine Other and have felt spiritually alienated and forsaken as a result; but with this alienation, this Fall and expulsion from the Garden, we have earned our autonomy. The sense of loss Dick experienced when the internal presence of the divine faded drove him to attempt suicide in 1976. Thus he had particularly compelling reason to see himself reflected in those ancients who likewise suffered grief at the loss of the divine voice.

The Right Car Door

It might seem like a risky gambit for a Gnostic Christian like Dick to seek insights into transcendent experience in neurobiology, because it readily plays into the hand of the opposition: Granting wholism, meaning, the spirit world, cosmic consciousness, and gnosis to the “equally important” right hemisphere readily reinforces the bigger materialist picture that the divine or the spiritual are a product of brain processes and nothing more.

Jaynes himself was a committed materialist. In his Introduction to his book, he describes that while working on it he himself experienced a hypnagogic voice telling him to “include the knower in the known,” which he took merely as an interesting example of the kinds of voices heard routinely by the ancients; however (as Gary Lachman points out in his excellent book, A Secret History of Consciousness

Jaynes himself was a committed materialist. In his Introduction to his book, he describes that while working on it he himself experienced a hypnagogic voice telling him to “include the knower in the known,” which he took merely as an interesting example of the kinds of voices heard routinely by the ancients; however (as Gary Lachman points out in his excellent book, A Secret History of Consciousness), it never occurred to Jaynes to actually listen to that voice or follow its recommendation.

Dick, however, very creatively found ways of integrating materialist scientific theories with his spiritual intuitions and beliefs, and he converged on his own view of the brain that harmonized the materialist views of Jaynes and other split-brain thinkers with an emerging neo-Platonic Gnostic theology and his five-dimensional view of spacetime.

Critically, our conscious self is alienated from its banished half existing in orthogonal (fifth dimensional) time, roughly equivalent to the Platonic world of forms. To realize our forgotten larger self, an anamnesis (unforgetting) is required, facilitated by the “luminous redeemer”; crucially it is aspects of our neurobiology and neurochemistry that keep us alienated from this perpendicular stream of time and form—among other things, the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. But, Dick felt, humanity is on the verge of the next phase in its evolution, when this brain barrier will give way to a restored bicameral consciousness, called the “Ditheon,” able to perceive the two worlds we live in—the private world and shared world (idios kosmos and koinos kosmos)—simultaneously, or “parallactically.” He felt his own experience anticipated this coming human shift.

Left Brain vs. No Head

Dick would have found a firmer scientific and theoretical basis for his concept of the Ditheon mind in Iain McGilchrist’s monumental 2009 reconsideration of the problem of brain hemisphericity and its relation to culture, The Master and His Emissary.

A mountain of evidence summarized by McGilchrist suggests that the left hemisphere, somewhat true to its stereotyped image, likes to nail down details, in sequential fashion, in an effort to control the world and avoid ambiguity at all costs. It likes to see things as definitive, static, and linear, and will jump to conclusions with unwarranted confidence. Language’s love of pinning labels on things goes along with this, although language is not solely rooted in the left hemisphere, as was once believed. The right hemisphere, in contrast to the left, sees the big picture and focuses more on caring for the world, finding meaning in it, and participating in it. This hemisphere is comfortable with indefiniteness, circularity (including circular notions of time), and inclusivity.

A mountain of evidence summarized by McGilchrist suggests that the left hemisphere, somewhat true to its stereotyped image, likes to nail down details, in sequential fashion, in an effort to control the world and avoid ambiguity at all costs. It likes to see things as definitive, static, and linear, and will jump to conclusions with unwarranted confidence. Language’s love of pinning labels on things goes along with this, although language is not solely rooted in the left hemisphere, as was once believed. The right hemisphere, in contrast to the left, sees the big picture and focuses more on caring for the world, finding meaning in it, and participating in it. This hemisphere is comfortable with indefiniteness, circularity (including circular notions of time), and inclusivity.

The interesting thing is that although the “wholist” right hemisphere is actually dominant in many respects, it can be lulled into a state of passivity by the frenetic instrumental behavior and extreme confidence of the left. In an argument that echoes but greatly nuances that of Jaynes, McGilchrist shows that the hemispheres’ opposed cognitive styles have tended to shift their balance because of cultural forces and fashions. We are currently, McGilchrist argues, in an extreme leftward swing: Under the parsing, instrumental left hemisphere’s direction, we have created a world of ecological and human exploitation and we have modeled our own society and even our own minds on the machine. Humanity’s present alienation comes from a kind of abdication of the throne, he says, letting the left-brain “emissary” take over while the right-brained “master” sleeps. If we persist on this cultural course, he suggests, we may end up creating a totally despirited social and technological environment that reproduces the kind of definitive mechanistic world the left hemisphere prefers to deal with, as a kind of materialistic self-fulfilling prophecy.

Unlike other neuroscientists interested in these problems, McGilchrist explicitly brackets the controversial question of the brain’s role in consciousness, concentrating instead on the inarguable role of the brain in giving structure to our experience. We live in two worlds, as philosophers have always pointed out, and any attempt to collapse them or subordinate one to the other is doomed to fail. Out of respect and deference for the non-definitive, McGilchrist even refrains from asserting (with a scientist’s usual left-brained force) that the divided nature of our mind is more than metaphorical. It is merely one way of looking at things.

Saying for instance that consciousness is a product of brain processes and nothing more would be a confident, left-hemisphere conclusion, but the left hemisphere isn’t always right and it cannot see the bigger picture. Yet instead subordinating matter to an all-encompassing notion of consciousness or some similar construct, as a host of recent anti-materialist thinkers like Deepak Chopra are doing (often invoking Quantum physics in their defense) may be similarly facile. We have to hold both perspectives—the materialist and the idealist—independently, simultaneously, even though they don’t add up.

McGilchrist goes so far as to concede that whether our two thought styles are really caused by the different functioning of two physical brain hemispheres (i.e., the whole neurophysiological basis for his argument) is ultimately less important than the fact that these cognitive styles exist as distinct, and the fact that they are fundamentally nonsymmetric and noncomplementary. This is what is so crucial and distinctive about his argument: These two worlds, these two alternative ways of perceiving, cannot be reconciled or collapsed into a synthesis; they don’t fit together or harmonize in any way.

In other words, it is not that the left hemisphere of the brain is in opposition to the right hemisphere. It is that the left hemisphere is in opposition to a standpoint that does not reduce things to material causes (such as brains or their hemispheres) at all. The left hemisphere is in opposition to no head.

Zooming in to the Void

The idea that at the core of our apprehension of the world is a nonsymmetrical opposition between two points of view that are utterly irreconcilable is also basic to Slavoj Žižek’s philosophy as the core idea of “parallax.” Various irreconcilable dualities in human knowledge (such as the wave/particle duality in physics or the reductive neuroscientific stance that consciousness is an illusion versus the meaningful world as humans really experience it) and even basic aspects of human experience like the irreconcilable rift between the sexes are reflections/effects of various fundamental divisions or antagonisms in our apprehension of the world, including things’ basic non-identity with themselves.

The latter division arises from the arbitrary and shifting relationship between the phenomenal world as it is digested in the imagination (the Imaginary) and the overlay of words and concepts that gives our mental images meaning (the Symbolic). In our daily consciousness we must pretend these match up harmoniously, that things have selves, but this is really a delusion. (This effect of the linguists’ “arbitrariness of the linguistic sign” is named in Buddhist philosophy as the doctrine of “no-self.”)

The latter division arises from the arbitrary and shifting relationship between the phenomenal world as it is digested in the imagination (the Imaginary) and the overlay of words and concepts that gives our mental images meaning (the Symbolic). In our daily consciousness we must pretend these match up harmoniously, that things have selves, but this is really a delusion. (This effect of the linguists’ “arbitrariness of the linguistic sign” is named in Buddhist philosophy as the doctrine of “no-self.”)

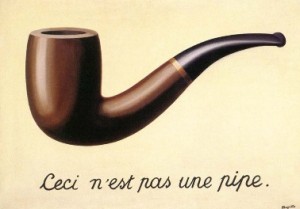

The impossibility of merger between the Symbolic and Imaginary becomes clear if you imagine a landscape and, over it, a projected contour or highway map. The belief in self-identity is the belief that the map can be inscribed in the landscape and merged with it. But even if you slapped a label or sign on every object in that landscape, saying “what it is,” would it really affect the is-ness of anything? If you painted the name of a road on the road, or even worked the name into the asphalt using differently colored tar, there would be vast parts of the pavement with no name, and you could crouch or zoom down in to any point in the landscape to a scale smaller than the label and arrive at the same unlabeled nothing.

The fact that a name cannot be merged with a thing is merely amusing when presented in the form of an object lesson like Magritte’s famous “This is not a pipe” painting. But there’s a real trauma in it. This subtle trauma can be experienced on any modern smartphone navigation app such as Google Maps. When you zoom in to a view a neighborhood more closely, the scale of the city blocks themselves enlarge, but the size of icons for landmarks and streets do not, nor do the map’s verbal labels. Zooming in further, you may disconcertingly zoom in so much that you lose all references: The name of a city or neighborhood hovers in a blank blue or gray emptiness, unattached to any image. This unsettling vacuousness, which seems like a glitch or imperfection in the software, is an experience of the Real.

We may attempt to flee or escape the Real through various “unitary” cheats—coming down firmly on either side of the materialism/idealism divide, for example: Being resolutely left-brained is one way to evade existential terror, just as being resolutely right brained is. But precisely according to the truism that a genius is the ability to hold two contradictory ideas simultaneously, advanced (and actually, ultimately blissful) thinking demands living in the excluded middle rejected by Aristotelian logic.

Theater of the Surd

Žižek emphasizes the parallactic nature of the Real as a counter to what he sees as facile New Age yin/yang images of harmony and complementarity, which strike him nothing better than a version of the naive literalism that conflates words and things. Lacan’s own adoption of the dollar sign, $, as his symbol for the “split subject,” the person decentered and alienated by language, could almost be seen as expressing precisely the same critique: It is as if either yin or yang (it doesn’t matter which one) is being jammed together with something that has been cut along a straight edge rather than an S-shaped curve. There is no complementarity to these halves, and instead there is a zone of inconsistency, illogic, doubling and gaps, and paradox.

This liminal zone where the consistency of the world breaks down, the Real, is exactly the realm of what Dick (borrowing a term from mathematics for irrational numbers) called the “surd” in the most breathtaking late entries in his Exegesis:

This liminal zone where the consistency of the world breaks down, the Real, is exactly the realm of what Dick (borrowing a term from mathematics for irrational numbers) called the “surd” in the most breathtaking late entries in his Exegesis:

When all the metaphysical and theological systems have come and gone there remains this inexplicable surd: a flurry of breath in the weeds in the back alley—a hint of motion and color. Nameless, defying analysis or systematizing: it is here and now, lowly, at the rim of perception and being. Who is it? What is it? I don’t know.

But even though this “place” of breakdown may appear to be part of the world’s landscape, it is really hovering between us and the landscape, as well as behind and within the landscape, like a weird optical illusion or hologram whose distance is impossible to fix.

Writers have generally described the Lacanian Real as whatever lies beyond the scope of human symbolism and imagination—the unnameable and the unrepresentable—but Žižek asks us to think of it as a mirage created by the constant oscillation among irreconcilable perspectives. It doesn’t exist, yet just as Dick says of the surd, it exerts a tug, an influence, on the world, the way the moon tugs at the Earth’s oceans. For Žižek, too, the Real is a pure semblance, a nothing, yet one that pulls on us, like a gravitational field bending our perceptions and our desires. Instead of being beguiled by the mirage, he says, we must penetrate it and attempt to grasp the multiple separate points of view that give rise to it, somehow apprehending them simultaneously.

Between Two Worlds

The mystical is the realm of the Real because it resists the dual pull of names and imagination. The place of mystical apprehension has always been described as precarious and difficult to enter and abide in deliberately—like a razor’s edge—precisely because the mind dislikes instability and uncertainty; it needs images and concepts to pin things down. Nevertheless, building the mental muscle of accepting inconsistency, cognitive dissonance, and even “impossibility” produces the ability to abide in the Real, balance on that razor’s edge, for longer and longer periods of time.

Indeed, although Žižek might be horrified to have his concept linked to Buddhism (which to him is basically ‘New Age obscurantism’), his description of parallax and void in The Parallax View

Indeed, although Žižek might be horrified to have his concept linked to Buddhism (which to him is basically ‘New Age obscurantism’), his description of parallax and void in The Parallax View comes close to capturing the actual felt experience of Zen meditation: an uncomfortable-at-first nowhere in which you cannot find your place or rest in secure signification or imagination. It is important to be clear: This discomfort has nothing to do with the physical discomfort of the seated postures emphasized by many contemporary Zen teachers in America—ritualistic painful sitting is not essential for Zen meditation. I’m referring to a mental/emotional discomfort, felt in the torso and whole body, as vague unease or physical dislocation. But this weird sense of placelessness becomes, over time, increasingly pleasurable and enriching, increasingly a home to return to and a source of strength and insight.

I’ve described elsewhere that David Lynch’s world of Twin Peaks, with its curtained spirit world shimmering in and out of view and its ominous sentient breeze rustling the pines, perfectly captures the transfigured sense of the world in the aftermath of meditation. Lynch, through his own daily mantra meditation practice, has been honing and deepening his access to the Real for over four decades, and Žižek (who lacks experience with the wordless) is quite mistaken when he dismisses this side Lynch as soft-headed. Lynch is a rigorous explorer of the Real, apprehending and expressing this zone and its effects in the only way possible. Žižek, for all his brilliance, can only talk around the Real, in endless symptomatic loops of wordy repetition that never get at the thing itself.

I’ve described elsewhere that David Lynch’s world of Twin Peaks, with its curtained spirit world shimmering in and out of view and its ominous sentient breeze rustling the pines, perfectly captures the transfigured sense of the world in the aftermath of meditation. Lynch, through his own daily mantra meditation practice, has been honing and deepening his access to the Real for over four decades, and Žižek (who lacks experience with the wordless) is quite mistaken when he dismisses this side Lynch as soft-headed. Lynch is a rigorous explorer of the Real, apprehending and expressing this zone and its effects in the only way possible. Žižek, for all his brilliance, can only talk around the Real, in endless symptomatic loops of wordy repetition that never get at the thing itself.

Another comparison would be Salvador Dali with his “paranoic-critical” images: landscapes and objects that are haunted by a latent image, an alternative way of perceiving the same landmarks. It is sort of in these terms that I imagine Dick’s experience seeing ancient Rome mapped onto modern Orange County: a kind of flickering imaginal overlay. In being able to see this, as well as detecting the ‘surdity’ (or Real) in the “trash stratum” of mundane existence, Dick felt that he was accessing a new Ditheon consciousness that, by integrating the brain hemispheres, was able to see two realities at once. Dick felt this capacity, which the Native American shamans described as being a “walker between two worlds,” was possibly the next phase in our cognitive evolution.

Making Flippy-Floppy

Possibly we would see Valis as a flicker of on-off, on-off, on-off, a flip-flop back and forth in its ceaseless dialectic that is in it but beneath it … All this is very much like what Heraclitus taught and he would probably have called Valis Logos. [Dick, Exegesis]

Ditheon perception could represent an evolutionary leap forward or a lapse into paranoia and madness—there’s probably a fine line (or heck, an overlap). I do think Dick is describing a capacity that mainstream, left-brained, materialist psychology has been far too hasty to deny the possibility of.

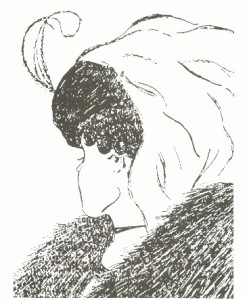

It is almost axiomatic in psychology that our perceptual-cognitive apparatus cannot tolerate contradictions or multiple meanings, and thus when faced with ambiguity, we are compelled to adopt some single stable interpretation, one that is consistent with the rest of our world, rejecting all contradictory data. Consider the classic multistable images we’ve all seen in Psychology 101 textbooks: Perceptual psychologists like to claim we can’t avoid falling into the trap of seeing either a young beautiful wife or a hideous mother-in-law (left), or either a duck or a rabbit (below). Our perception may flip-flop, but it is always stated as fact that we can’t see a duck and a rabbit (or a wife and a mother in law) simultaneously.

It is almost axiomatic in psychology that our perceptual-cognitive apparatus cannot tolerate contradictions or multiple meanings, and thus when faced with ambiguity, we are compelled to adopt some single stable interpretation, one that is consistent with the rest of our world, rejecting all contradictory data. Consider the classic multistable images we’ve all seen in Psychology 101 textbooks: Perceptual psychologists like to claim we can’t avoid falling into the trap of seeing either a young beautiful wife or a hideous mother-in-law (left), or either a duck or a rabbit (below). Our perception may flip-flop, but it is always stated as fact that we can’t see a duck and a rabbit (or a wife and a mother in law) simultaneously.

The philosopher Wittgenstein noted, however, that it is at least possible to say “It’s a duck-rabbit” and to recognize the image as such; I believe it may also be possible, with difficulty, to see its dual reality. If you hang a duck-rabbit on your wall and stare at it in idle moments for a few weeks, it starts to change. The two aspects themselves morph and distort, and eventually, I find, the flip-flop actually accelerates, becoming more of an anxious flicker; if you try, you can almost, for the briefest instant, see just an ambiguous shape or an unrelated object (for instance, some kind of sinister mutant squid or vegetable). This breakdown of the sense of the image reminds me of what occurs when you repeat a familiar word over and over 50 or 100 times: It temporarily loses its meaning and seems strange.

The philosopher Wittgenstein noted, however, that it is at least possible to say “It’s a duck-rabbit” and to recognize the image as such; I believe it may also be possible, with difficulty, to see its dual reality. If you hang a duck-rabbit on your wall and stare at it in idle moments for a few weeks, it starts to change. The two aspects themselves morph and distort, and eventually, I find, the flip-flop actually accelerates, becoming more of an anxious flicker; if you try, you can almost, for the briefest instant, see just an ambiguous shape or an unrelated object (for instance, some kind of sinister mutant squid or vegetable). This breakdown of the sense of the image reminds me of what occurs when you repeat a familiar word over and over 50 or 100 times: It temporarily loses its meaning and seems strange.

This “meaningless” apprehension, which would be a kind of peace-making with cognitive dissonance, is exactly the aim of contemplative techniques like Zen: Once you somewhat build the muscle of non-attachment and can resist cognitively rushing in to an involvement (or interpretation) with the seen, things begin to manifest in their “suchness”—that is, just as they are—initially for brief flickering instants or a few seconds; eventually you can abide in this precarious in-between place for longer durations.

Because they pose such a challenge and invitation, I suspect that multistable images like duck-rabbits would be ideal visual koans for intensive meditation. (Some of Magritte’s similarly ambiguous images can also function this way.)

The Real and the Paranormal

Paranormal phenomena belong to this indeterminate, hard-to-see landscape where duck-rabbits frolic and play, because they evade nearly all attempts to pin them with concepts and labels. This quality has been described by some researchers as “tricksterish,” but a future theory of paranormal phenomena could profitably adopt Lacanian language instead. The paranormal is about as “Real” as it gets.

UFOs and related phenomena, because of their maddening ambiguity, make great tools for meditation. I am also beginning to think that the reverse may also be the case: Developing ones parallactic or ‘Ditheon’ mental capacity through engaged meditation and staring at duck-rabbits is possibly the necessary prerequisite for experiencing, and probably making progress understanding, paranormal phenomena.

For example there are scattered, tantalizing hints throughout the UFO literature that they or their associated intelligences might be somehow drawn to persons in meditative states. Examples include Whitley Strieber’s habit of Zen meditation with his visiting grays; the observation by Skinwalker Ranch researchers that meditation might act as bait for the bizarre phenomena they observed; or even the reputed tendency of UFOs to appear near Nikolai Kozyrev’s lab in Siberia when his mirrors were being used to focus mental energy. But it could simply be that UFOs are all around and it is just our ordinary left-brained definitive minds that keep us from seeing them.

It is also no accident that a mystical practice (or “yoga” in the ancient Patanjali sense—which just meant meditation) is widely regarded as a necessary prerequisite to build psi ability. Even outside of an Eastern religious or yogic framework, many writers on ESP have described meditative states as essential, both for getting outside our categorical/definitive/conceptual left brains (what Ingo Swann called “analytical overlay”) and for temporarily setting aside or at least minimizing our petty egos and biases and distort our interpretations of what we see.

Lynch thinks we could create a better, more humane world if everybody meditated. I would add that getting everyone to meditate might create a more paranormal world, too.

“McGilchrist goes so far as to concede that whether our two thought styles are really caused by the different functioning of two physical brain hemispheres (i.e., the whole neurophysiological basis for his argument) is ultimately less important than the fact that these cognitive styles exist as distinct, and the fact that they are fundamentally nonsymmetric and noncomplementary. This is what is so crucial and distinctive about his argument: These two worlds, these two alternative ways of perceiving, cannot be reconciled or collapsed into a synthesis; they don’t fit together or harmonize in any way.”

Hi Eric, I think I disagree with your interpretation of McGilchrist’s theory. The two brains serve different but complimentary functions, are dependent on each other for feedback, and are necessary for human survival as they assist us in navigating through an unknown terrain (any creative process). I’d imagine them as Escher’s drawing hands. Or an alchemist’s mercury and sulphur.

Gary Lachman, whom you quoted, had written an illuminating review of the book in the Los Angeles Review of Books: http://www.dailygrail.com/blogs/Gary-Lachman/2012/2/The-Master-and-His-Emissary-Are-Two-Brains-Better-One

Quoting some of his review:

—

“It’s like looking through a microscope and at a panorama simultaneously. The right needs the left because its picture, while of the whole, is fuzzy and lacks precision. So it’s the job of the left brain, as “the Emissary,” to unpack the gestalt the right presents and then return it, increasing the quality and depth of that whole picture. The left needs the right because while it can focus on minute particulars, in doing so it loses touch with everything else and can easily find itself adrift. One gives context, the other details. One sees the forest, the other the trees.”

“McGilchrist argues that the hemispheres are actually in a kind of struggle or rivalry, a dynamic tension that, in its best moments (sadly rare), produces works of genius and a matchless zest for life, but in its worst (more common) leads to a dead, denatured, mechanistic world of bits and pieces, a collection of unconnected fragments with no hope of forming a whole. (The right, he tells us, is geared toward living things, while the left prefers the mechanical.) This rivalry is an expression of the fundamental asymmetry between the hemispheres.”

—