The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

What’s Expected of Us in a Block Universe: Intuition, Habit, & ‘Free Will’

Ted Chiang is an SF writer after my own heart. At every stage in my own investigation of time loops, someone sends me yet another Chiang story that addresses exactly the issues I’ve been working on. What’s more, his stories seem to act as attractors for precognitive and time-looping experiences. I’m sure his new collection Exhalation, which compiles some time-related stories that have been floating around in various publications and on the Internet for several years, will have already precipitated countless precognitive dreams.

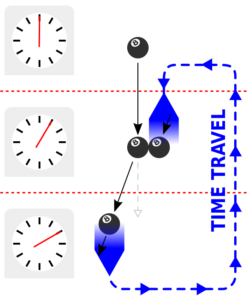

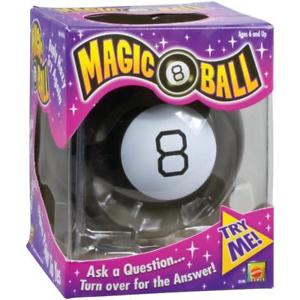

“What’s Expected of Us” is one of those stories. This story, originally published in Nature in 2005, is about a little device with a light, a button, and a precognitive circuit (or “negative time delay”) linking them. The light goes off one second before the button is pressed, and cannot be fooled no matter how hard the user tries. Users treat it like a game, trying to “beat” or outwit the light, but find they cannot. The device becomes super popular, people play with it addictively, but roughly a third of users succumb to a kind of hopelessness and immobility called “akinetic mutism,” because of what the device has taught them about the nonexistence of free will, the futility of trying to change their fate. “Like a legion of Bartleby the Scriveners, they no longer engage in spontaneous action.”

“What’s Expected of Us” is one of those stories. This story, originally published in Nature in 2005, is about a little device with a light, a button, and a precognitive circuit (or “negative time delay”) linking them. The light goes off one second before the button is pressed, and cannot be fooled no matter how hard the user tries. Users treat it like a game, trying to “beat” or outwit the light, but find they cannot. The device becomes super popular, people play with it addictively, but roughly a third of users succumb to a kind of hopelessness and immobility called “akinetic mutism,” because of what the device has taught them about the nonexistence of free will, the futility of trying to change their fate. “Like a legion of Bartleby the Scriveners, they no longer engage in spontaneous action.”

People used to speculate about a thought that destroys the thinker, some unspeakable Lovecraftian horror, or a Gödel sentence that crashes the human logical system. It turns out that the disabling thought is one that we’ve all encountered: the idea that free will doesn’t exist. It just wasn’t harmful until you believed it.

This wonderful little story cuts to the heart of the issues, as well as misconceptions, that surround the question of free will and the threats to it that we imagine are posed by precognition in a block universe, where the future in some sense already exists.

Americans have trouble with anything that appears to threaten the idea of free will. Ours is a highly freedom-loving and individualistic society, and we love the idea that we are free agents, willful determiners of our lives. We think of ourselves as cars who can go anywhere we please, even off-road, not trains fixed to a single track. If we think of the future as “already” holding something in store for us, we delimit that something to destiny, a kind of dotted line around the person we might become but aren’t obliged to. A destiny is a future that awaits our freely willed actions to fulfill or not fulfill, depending. This is in sharp contrast to the ancient notion of fate as a preordained future that will always outwit our best efforts at evasion. Classical tragedies like Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex were thought experiments about fate and how we fulfill it precisely by trying to escape it.

“What’s Expected of Us” is a mini Oedipus Rex for an age of fidget-spinners. But we don’t need to look as far back as fifth Century BC Athens for models for the Predictor. The first thing Chiang’s story reminds me of—and I’d bet the author had it in mind when he wrote the story—is an astonishing 1983 discovery by neuroscientist Benjamin Libet: The nerves in participants’ fingers readied to fire (“lit up” you might say) a fifth of a second before participants consciously decided to move their finger. Libet’s discoveries prompted other psychologists to prove that we are not really masters in our house. Experiments by Daniel Wegner and others seemed to show that we instead take credit for actions per our culturally ingrained ideas of agency. The ego sees something it likes—a successful motor action, say—and proudly goes “I did that.” It sees something it didn’t like, like tripping and falling, and chalks it up to accident or to some external force or influence impinging on it.

Conscious will as studied in psychology laboratories is not exactly the same thing as the philosophers’ free will and the question of physical determinism. But it offers an interesting entry point to the question of what we really lose by jettisoning that philosophical security blanket of imagining that the future remains open ended and under our control. If the conscious mind is a spectator, what is it we’re really talking about when we’re talking about free will? Is “akinetic mutism” really the result of giving up on our belief in it?

Seize the Fish!

In Chiang’s story, Predictor users slump into apathy and silence because they decide their actions (versus nonactions) don’t matter. And part of their problem is they can’t shake their feeling of free will even when they know it isn’t “real” in some larger sense. Lying in bed and not responding to one’s surroundings is just as much an action as getting up and seizing the day (“Carpe diem!“) in the belief that we are agents of our lives—because our thoughts and interpretations are just as much “enacted” as our physical movements.

But what the Zen masters of China and Japan discovered is that direct experience of the illusory nature of free will actually leads to liberation, not apathy. There is a training-wheels phase, though: Trying to escape the question of free will/no free will and directly experience pure spontaneity is a familiar experience for any beginner at Zen practice, in fact. What one discovers is the ridiculousness of the pose of “not acting.” You can’t escape your thoughts. Nor can you escape the will of your body. (Hunger alone will drive you to go to the kitchen and eat, ignoring your mental bafflement: “hey, is this freely willed, or not??”)

But what the Zen masters of China and Japan discovered is that direct experience of the illusory nature of free will actually leads to liberation, not apathy. There is a training-wheels phase, though: Trying to escape the question of free will/no free will and directly experience pure spontaneity is a familiar experience for any beginner at Zen practice, in fact. What one discovers is the ridiculousness of the pose of “not acting.” You can’t escape your thoughts. Nor can you escape the will of your body. (Hunger alone will drive you to go to the kitchen and eat, ignoring your mental bafflement: “hey, is this freely willed, or not??”)

Ultimately, passively observing the flow of stuff in our head, and detaching ourselves from our actions and their outcomes, is highly freeing, not to mention empowering. What serious meditators discover is that, unburdened from the baggage of thinking about their freedom or unfreedom, their thoughts become more rewarding and their actions and words more skillful. The less free we imagine we are, the more free we feel. It’s the same joy anyone feels whenever they practice any complex skill and become so good at it that the practice becomes effortless, performed in a state of flow. Shao-lin kung-fu masters are not worried about their free will. Neither are the wise heptapods in the movie Arrival, based on Chiang’s “Story of Your Life.”

The akinetic mutists of “What’s Expected of Us” are simply stuck in that awkward in-between period, on the way to becoming enlightened Zen masters or heptapods basking blissfully in the eternity of the block universe.

The question of human precognition and free will should not be divorced from the question of skill performance. Anyone who knows how to drive a car well, be super witty on a date, or swiftly change a baby’s diaper with one hand knows that we are most effective when we don’t think about what we are doing but just do it. Research on “psi” also shows that it is an unconscious, un-willed function or group of functions. Laboratory experiments strongly support something like presentiment (“feeling the future”), and there is reason to think it could be a pervasive feature or even a basic underlying principle of our psychology. I am not the first to suggest that Libet’s findings actually reflect the tip of the iceberg of presentimental functioning.

Indeed, people who express strong “intuitive” ability often seem to do so in the context of some automatized and highly enjoyable/thrilling motor skill—piloting a plane, martial arts, mountain climbing, but also things like musical performance, stage magic, and other arts (including hammering away at a typewriter for a penny or a dollar a word). I consider dowsing to be the model, the most basic form (or stem cell) of psi as presentiment/precognition: using motor reflexes to tap into a forthcoming reward via the ideomotor effect. And whether you are a race car driver, a remote viewer, or a dowser, self-consciousness that might include an awareness of “making choices” is the last thing you want.

The relation of our conscious will to our skilled actions may be something like a time loop, in other words. We go through life behaviorally divining successful or rewarding outcomes, which we then reflect on afterward, perhaps misinterpreting that retrospective reflection as agency. But another way of putting this is that we may be “pulling our meat puppet’s strings” from a point farther along our timeline. What we interpret in hindsight as our will or intention is really the reward of having had an accurate premonition of a future successful action.

Caudate-Putamen

Interestingly, there is now potentially some neurobiological support for the linkage of “psi” specifically with compulsive, habitual, or automatic—in other words, distinctly not “consciously willed”—behaviors.

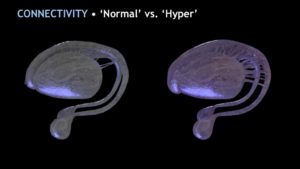

This past winter, a few blogs including Terra Obscura announced the highly intriguing findings of Garry Nolan (Rachford and Carlota Professor in the Dept. of Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford School of Medicine) and forensic neurologist Christopher “Kit” Green (Depts. of Diagnostic Radiology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences at Wayne State School of Medicine and Detroit Medical Center) on a brain area called the caudate-putamen. In the course of working with a population of 135 high-performing military and intelligence personnel who had suffered injuries from anomalous encounters in the line of duty, the researchers noted an additional feature in a few patients’ MRIs. Twenty of the most high-functioning and “intuitive” of this group, as determined from medical and psychological records, displayed significantly enhanced connectivity between their caudate and putamen, compared to the general population.

This past winter, a few blogs including Terra Obscura announced the highly intriguing findings of Garry Nolan (Rachford and Carlota Professor in the Dept. of Microbiology and Immunology at Stanford School of Medicine) and forensic neurologist Christopher “Kit” Green (Depts. of Diagnostic Radiology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences at Wayne State School of Medicine and Detroit Medical Center) on a brain area called the caudate-putamen. In the course of working with a population of 135 high-performing military and intelligence personnel who had suffered injuries from anomalous encounters in the line of duty, the researchers noted an additional feature in a few patients’ MRIs. Twenty of the most high-functioning and “intuitive” of this group, as determined from medical and psychological records, displayed significantly enhanced connectivity between their caudate and putamen, compared to the general population.

The work of this sample of persons is secret, as are the circumstances of the injuries that brought them to the attention of the researchers in the first place; but the implication is that those who showed the enhanced connectivity are the kinds of people who have “Spidey sense,” who could instinctively guide you down the right path in enemy territory because they sense danger down the left. A sample of remote viewers for whom MRI scans were available all showed the same caudate-putamen biomarker.

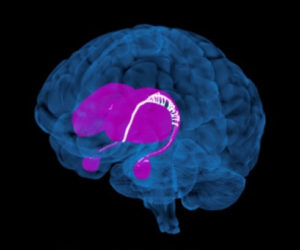

The caudate-putamen, also known as the dorsal striatum, is thought to be a kind of “hub” that integrates information from across the brain and translates that information into motor actions. Nolan and Green’s sample show exceptionally high parallel and rapid processing of what in very recent years has emerged as functions of the dorsal striatum’s receipt of incoming sensory information, and subsequent integration in the prefrontal cortex.

In presentations of their finding, the researchers have called the dense, spoke-like connectivity in these high-performing individuals an “antenna”—there is indeed something suggestive of an antenna in its visual appearance—but they have not tested the notion of any electromagnetic receiving or transmission capability, and they recognize that its precise functional role in intuitive skill performance is a matter of speculation at this point. But they did not find this feature at all in brain scans from a retrospective sample of over 300 “ordinary” people—that is, patients who had no medical histories of high executive functioning, and who served as single-blind controls.

And interestingly, it appears to run in families. The researchers fortuitously had access to siblings, parents, and children of some subjects—3 or 4 family members in a few cases—and the MRI finding was present in those individuals also. Consequently, Nolan established a genetic pilot study that is now underway, to learn more about this feature and its heritability. It is still unknown whether and to what extent life experience or training may also influence it (i.e. the brain’s plasticity). When helpfully answering my questions by email, they also stressed that their finding about the caudate-putamen in this sample has not been peer-reviewed, nor yet published, nor subjected to double-blind verification.

“Antenna” is a sexy term, and it got the attention of many people who are interested in intuitive and psychic functioning. But if further research supports this brain feature and its relation to high performance, I have a hunch “Predictor” might turn out to be an even better term for what Nolan and Green have found.

The Jouissance System

The study of psychic phenomena has always adopted some model of information-transfer, rooted in telecommunications technologies of the day. The telegraph dominated the thinking of Frederic Myers with his theory of “telepathy” in the last two decades of the 19th Century. In the Rhines’ day, radio was an obvious metaphor for ESP. And later remote-viewing researchers naturally likened the practice to tuning in on a TV signal. Today, the metaphors of nonlocality and entanglement between psychics’ minds and the wider universe are hot. But if “psi” is really precognition, then nothing necessarily needs to be sensed or detected from outside the body or even outside the nervous system. It would be the nervous system’s connection to itself across time that matters.

In that view, a soldier with Spidey sense might not actually be receiving some kind of waves coming from the IED down the left path and thus leading her squad down the right path. Her brain might instead be post-selecting on the ambivalent future reward of having taken the right path and then heard the explosion and screams of some other less-fortunate squad that took the left. Intuition would be a premonition of ambivalent future reward. If that’s the case, then the neurotransmitter dopamine and the reward circuits that use it might have a lot to do with this disturbing-yet-rewarding “signal” from the individual’s future.

This is why I was (selfishly) a bit excited to hear about Nolan’s and Green’s discovery. In interviews such as his recent appearance on Café Obscura, Nolan has highlighted the caudate and putamen’s role in intuition, but one way of looking at intuition is generating actions from available information quickly, bypassing conscious, deliberate decision-making. When we talk about bypassing those more deliberate processes, we’re essentially talking about making our responses automatic. In a lot of neuroscience literature, the dorsal striatum is not only associated with intuition but also with habits and compulsions—actions we don’t necessarily want to engage in but do so anyway, feeling we have no choice. In other words, in the brain, intuition is closely tied to habit and to the most un-“freely willed” of our behaviors, such as compulsions and addictions.

This is why I was (selfishly) a bit excited to hear about Nolan’s and Green’s discovery. In interviews such as his recent appearance on Café Obscura, Nolan has highlighted the caudate and putamen’s role in intuition, but one way of looking at intuition is generating actions from available information quickly, bypassing conscious, deliberate decision-making. When we talk about bypassing those more deliberate processes, we’re essentially talking about making our responses automatic. In a lot of neuroscience literature, the dorsal striatum is not only associated with intuition but also with habits and compulsions—actions we don’t necessarily want to engage in but do so anyway, feeling we have no choice. In other words, in the brain, intuition is closely tied to habit and to the most un-“freely willed” of our behaviors, such as compulsions and addictions.

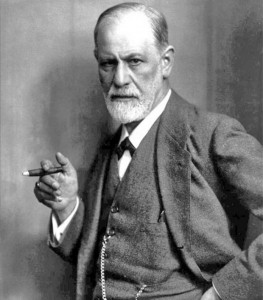

Like other parts of the reward circuit, the cells of the dorsal striatum, including those spoke- or antenna-like connections identified by Nolan and Green, predominantly use dopamine for signaling. It is part of what I think of as the brain’s “jouissance system.” Jouissance is just a fancy French word for the drive that takes over in a compulsive disorder like a neurosis or an addiction—a reorientation of the salience of incentives away from some euphoric payoff or reward into various cues associated with it, which perpetuate the drive. Freud called it the “compulsion to repeat,” and for him it was the basis of neurotic behavior.*

If anomalous cognition or psi is “really” (or mainly) precognition, it makes sense that brain areas governing habit and compulsivity might figure prominently in its neurobiology. The reason is that computation across the fourth dimension depends on repetition: The brain’s ability to make some sense of information coming down the pike requires self-consistency over time. Just as a New Yorker will have an easier time understanding a time traveler from a 25th Century where they still speak recognizable English in New York versus a future where everyone had switched to Russian, the more we expect our reactions to stimuli in ten minutes or a year will be the same as now, the more decontextualized information coming from our future can make sense and be useful in guiding behavior. Compulsions and habits, which in many ways are just overlearned skills, create the necessary self-expectations that might serve as the cipher-key of information back-flowing from an individual’s future.

A “Predictor” circuit could in a sense be likened to an antenna, but in the fourth dimension. Just like some antennae appear as grids, parallel lines, or “repetitions” in space, a fourth-dimensional biological antenna would likely involve repetition of behaviors over time.

iPredictor™

Here is where we come back to the theme of “free will” and Ted Chiang’s story. Not unlike people in the grip of an addiction or a compulsion, intuitive and highly skilled people are those who readily make decisions without thinking. Their high performance, as well as their “psi,” is an outside-of-conscious-will phenomenon. And it may be the best model for thinking about the unconscious in relation to consciousness: The unconscious leads the way, but it may be in a necessary partnership with the 20-20 hindsight of conscious awareness. The squad leader’s psi/jouissance needs that confirmation in the form of the screams coming from the other path. The time-looping relation to future confirmation is crucial.

There is a tendency to think of precognition as some kind of superpower enabling the individual to scan various options ahead and select the optimal one, like a kind of radar. But if in fact precognition is just what Freud called “the unconscious” in many or all its manifestations, then we need to rethink its role in our lives. it is not, in that case, some “super” faculty giving us the ability to spot dangers and avoid them—which could lead to the paradoxical situation of preventing a foreseen outcome. It is instead the faculty that prepares us, cushions us, for alarming news and close calls that do lie ahead in our un-freely-willed future.

There is a tendency to think of precognition as some kind of superpower enabling the individual to scan various options ahead and select the optimal one, like a kind of radar. But if in fact precognition is just what Freud called “the unconscious” in many or all its manifestations, then we need to rethink its role in our lives. it is not, in that case, some “super” faculty giving us the ability to spot dangers and avoid them—which could lead to the paradoxical situation of preventing a foreseen outcome. It is instead the faculty that prepares us, cushions us, for alarming news and close calls that do lie ahead in our un-freely-willed future.

If there is something like a radar, it would really (in this view) be our ordinary conscious thought processes that consider counterfactual situations and scenarios and make us take wise precautions and adjust our behavior based on past errors. The anxious brain lying awake at 3AM consciously worrying about disasters and dangers and agonizing over mistakes is the real radar that steers us clear from undesirable outcomes ahead. However, in a block universe, action verbs like “steer” need to be seen more statically, as parts of four-D time loop formations. “Steering toward success” needs to be rephrased as “discovering you are the person who was successful.” Overhauling our language to deal with a block universe is a massive subject, for another post (or book).

But the bottom line is: I will be the first in line at the Apple store when the Chiang-inspired iPredictor goes on sale in May, 2026. Far from creating a population of akinetic mutists, it will act as a material(ized) koan, fast-tracking users to Satori.

Postscript: Failure Is Not an Option

People who find the idea of precognition, retrocausation, and time loops interesting are often of an occultist bent, and I have been asked several times how the block universe that allows precognition can be reconciled with the active intention setting that a magician might utilize. And what about the idea that thoughts and intentions create our reality? I often think of my friend Mitch Horowitz’s brilliant writings on New Thought (such as his recent book The Miracle Club), and how determinism in a block universe seems on the surface so antithetical to the outlook he describes: that thoughts are causative.

Sometimes when two ideas seem diametrically opposed, zooming in reveals a closer kinship. For one thing, I agree with Mitch’s basic assertion that thoughts are causative. Where I may differ is in the direction of their causation. If our unconscious behaviors are premonitory of what we think of as our will, if what we “precognize” with our bodies and our automatic (unconscious) actions is our future conscious thoughts, realizations, and “intentions,” then those thoughts are by definition retro-causing the past. Our conscious realizations and intentions for the future are actually writing (or “having written”) our past life scripts. They do this not just by reordering our memories in the present (Slavoj Žižek’s cautious, not-quite-retrocausal, not-quite-Gnostic position), but by actually directing our actions from the future and influencing our younger selves.

Sometimes when two ideas seem diametrically opposed, zooming in reveals a closer kinship. For one thing, I agree with Mitch’s basic assertion that thoughts are causative. Where I may differ is in the direction of their causation. If our unconscious behaviors are premonitory of what we think of as our will, if what we “precognize” with our bodies and our automatic (unconscious) actions is our future conscious thoughts, realizations, and “intentions,” then those thoughts are by definition retro-causing the past. Our conscious realizations and intentions for the future are actually writing (or “having written”) our past life scripts. They do this not just by reordering our memories in the present (Slavoj Žižek’s cautious, not-quite-retrocausal, not-quite-Gnostic position), but by actually directing our actions from the future and influencing our younger selves.

So in other words, I think our thoughts are efficacious, and specifically in our past—that is to say, in the past (or prehistory) of the thought. This kind of retrocausation may be operative on millisecond or second scales, such as in the presentiment research of Dean Radin or the “feeling the future” studies of Daryl Bem, but also over days, years, and decades. A macro model for this is dreams, of the sort I’ve discussed frequently on this blog. If a person’s day is even slightly affected by a dream (even just in the mere act of writing it down) and the dream consists of or contains precognitive material—which it’s even conceivable all dreams do—then information from the future has exerted a shaping force on the past … even if we misinterpret the dream. If this time-looping logic goes all the way down, even to the cellular level of thoughts in the brain, as I strongly suspect it will turn out to, then our thoughts are causative of our histories. We ongoingly shape ourselves into the past. Our past is an effect of our future.

Note that this is not the same thing as “changing the past”—the idea that we could somehow meddle in and alter our timelines—the Mandela effect and whatnot. How would we ever know our timeline had changed? We can however produce improved outcomes in our near future when we realize how we have contributed to shaping our past. We can sow seeds in the past for a better tomorrow. This is exactly the payoff of the “dream paleontology” I described a few posts back, and it will turn out to be the motto or philosophy of our timefaring descendents.

We need to remember: What we think we “know” of the past (or present) is at best a tapestry of suppositions, assumptions, and interpretations. Most modern conceptual frameworks for understanding the past make no room for a teleological influence and thus we think of the past as fixed and untouchable by any later influence … but that’s just a modern, post-Enlightenment failure of imagination, not a real limitation on reality. Increasingly, evidence shows our commonsense view of causality only going in a forward direction is simply wrong—in Time Loops I call it “folk causality.” We simply need to update our imaginations.

We have no proof yet, but my hunch is that the underlying principle in precognition will probably turn out to be retrocausal processes in quantum biology—perhaps quantum computation in molecular structures controlling brain plasticity (microtubules). One way we already know quantum processes manifest in biology is the phenomenon called quantum tunneling: the apparent fast-forwarding of unmeasured particles toward their destinations. (We know photosynthesis and enzymatic actions depend on it, for instance.) The retrocausal interpretation of quantum mechanics reframes this: It is the “measurement” (or just, terminal interaction) that retro-determines the particle’s path.

This quantum fast-forwarding toward what to our eyes appear like “intended” outcomes could be the X factor separating life from lifeless matter in organic molecules, the missing “vital” principle underlying life. It would force us to reincorporate “purpose and desire” into our understanding of living systems. And it would scale up in nervous systems, which tend (to some greater-than-chance degree) to post-select on survival and rewards in the organism’s future.

This allows us to “flip” the New Thought idea that success is built on mind. Mind is really built on success. Mind IS success. And since on a basic level that “success” is post-selecting the actions leading to it, there is no “other” world of “failure” (or “missing”) out there as an option for where a particle could go or what an organism could do. That Spidey-sense squad leader automatically took the right path without the IED, and there was no alternative or counterfactual reality where she took the left path instead. Failure is literally not an option in a retrocausal universe, at least on the most basic level of particles. The Mind scales up this “tunneling toward the optimum” principle and utilizes it to create the splendiferous 4-D formations that are our biographies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Many thanks to Kit Green and Garry Nolan for sharing their research and slides with me, and for answering my many questions. My interpretations of their finding are entirely my own. Thanks also to Michael Garfield of the Future Fossils podcast for alerting me to Chiang’s “What’s Expected of Us.”

NOTES

** A similar shift of orientation toward cues rather than payoffs also reflects the intrinsic reward that takes over in practioners of highly trained skills. For a race car driver, the pleasure is in the driving, not just in crossing the finish line—in fact, the latter is a bit of a disappointment, because it means the race is over. Presumably some of the intuitive high-performers in Nolan’s and Green’s sample are fueled by the same dopamine drive, a kind of jouissance from always being on the edge of peril or risk.

Edges of Forever: Time Travel and the Stories That Might Have Been

“We can’t imagine our lives without the unlived lives they contain.”—Adam Phillips, Missing Out

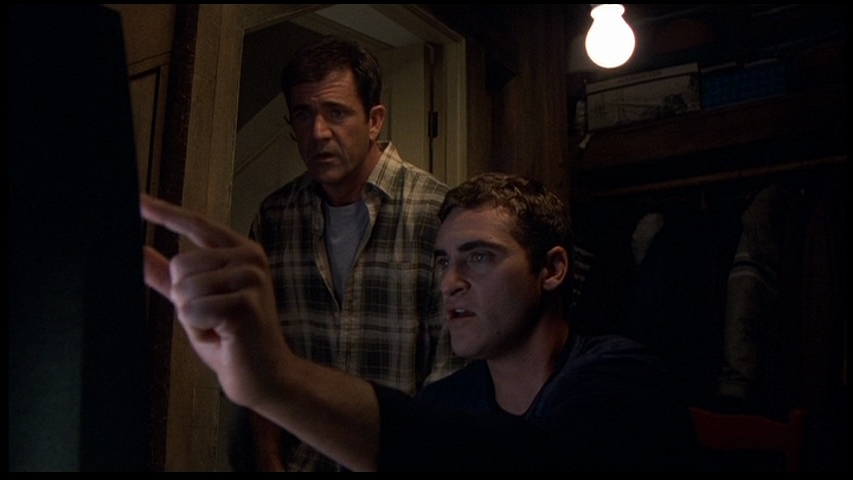

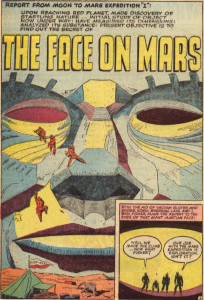

Ship’s Log: star-date 3139.0. Having tracked unusual spacetime ripples to their source, the Starship Enterprise now threatens to be ripped apart as it struggles to maintain its orbit over an uncharted, weirdly time-disturbing planet. There is chaos on the bridge. Mr. Sulu, injured by his exploding control panel, is brought back to life by an injection of an adrenaline-like wonder-drug called Cordrazine … but just then, another spacetime ripple causes Dr. McCoy to accidentally inject himself with a megadose of the stimulant. Raving mad, McCoy dashes from the bridge as the rest of the crew struggle to save the ship, and he beams himself down to the planet that is causing all the spacetime havoc.

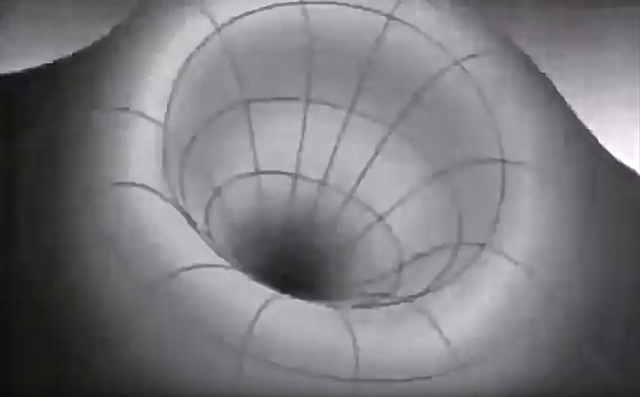

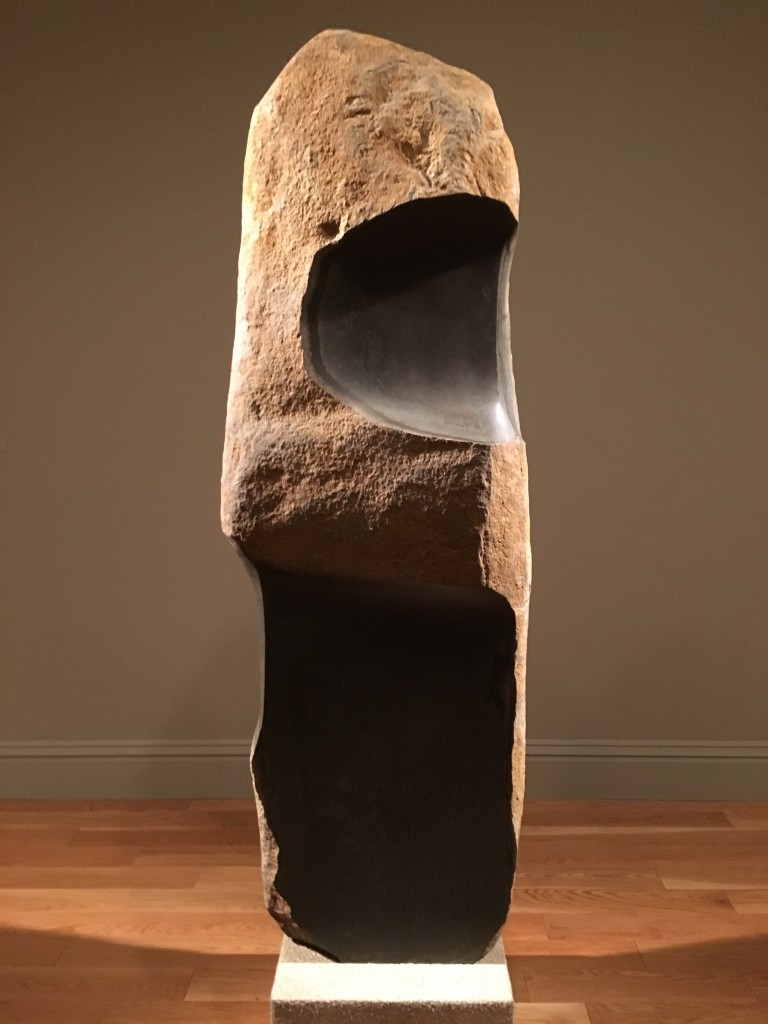

Pursuing the mad Doctor to the surface, Kirk, Spock and several crewmembers find they are in the ruins of an incredibly ancient and vast city; at its heart is an enormous loop pulsating with light. This object awakens to their presence and announces, in a deep echoing voice, that it is the Guardian of Forever, a sentient portal through time. It begins showing its visitors scenes from Earth’s history, and just as it displays a street scene from 1930s America, Dr. McCoy, who had been hiding behind a nearby rock, dashes through the portal.

Pursuing the mad Doctor to the surface, Kirk, Spock and several crewmembers find they are in the ruins of an incredibly ancient and vast city; at its heart is an enormous loop pulsating with light. This object awakens to their presence and announces, in a deep echoing voice, that it is the Guardian of Forever, a sentient portal through time. It begins showing its visitors scenes from Earth’s history, and just as it displays a street scene from 1930s America, Dr. McCoy, who had been hiding behind a nearby rock, dashes through the portal.

The landing party suddenly finds that the Enterprise has disappeared from orbit overhead. Somehow Dr. McCoy, centuries in the past, changed history, leading to a present with no Enterprise to return to, and perhaps no Star Fleet … maybe even no Earth. So Kirk and Spock have to go through the portal themselves to try and make things right.

Thus begins “The City on the Edge of Forever,” perhaps the most famous and best-loved original series Star Trek episode. Even now, over half a century since it first aired, it remains a great hour of television, with some of the most moving, funny, and (yes) campy moments in the whole series. It is also one of the few Trek episodes to attain a kind of tragic gravitas. Joan Collins delivers a memorable performance as Kirk’s love interest Edith Keeler, the Depression-era peace activist whose sacrifice to the wheels of history is required to return the river of time to its former course.

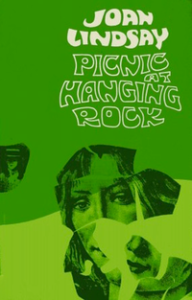

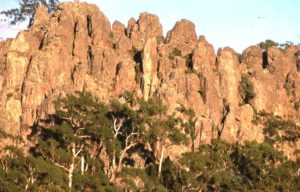

Even though it is just a piece of network TV from a much more innocent era, “City” is arguably one of the most influential time travel narratives of all time. I’ll wager that more people have seen (and remember) this one episode of Gene Roddenberry’s NBC series than have ever read H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine, for instance. It also came to define the life of its famously cantankerous scriptwriter Harlan Ellison in ways that weirdly—really weirdly—mimicked the original treatment and teleplay he penned for it. This is no accident, as I believe it is yet another case of the literary-creative precognition that is so prevalent among imaginative writers. As we saw with Joan Lindsay and her novel Picnic at Hanging Rock, these cases always fractally swirl around “time gimmicks” of one sort or another. Ellison’s time machine (which only became the sentient stone-loop Guardian in the filmed episode) made the perfect “strange attractor” for a precognitive writer’s soul. And as in Lindsay’s case, it was the alterations made to Ellison’s story by other people that created this defining time warp in his life.

Anger Issues

Trek nerds know what went down, at least in its rough outlines, and Marc Cushman gives all the sordid details in the first volume of his essential tome, These Are the Voyages. Ellison, already a respected writer of SF stories and screenplays for series like The Outer Limits, was commissioned by Roddenberry in 1966 to write an episode for the first season of his new space series. The treatment Ellison delivered contained the brilliant premise we all know and love—Kirk travels into the past and falls in love with an idealistic peace activist whom he must then allow to die … but it was also totally unfilmable as written, at least to fit within a single hour of network TV. Also, it contained dark elements that were way out of character with what Roddenberry envisioned for his still-unaired utopian show.

Ellison’s version opens with a drug deal. The ship’s navigator, hopelessly addicted to an alien narcotic called the Jewels of Sound, purchases some of the stuff from a shady officer named Beckwith. We fade to the bridge, where the navigator, now high as a kite, nearly destroys the ship and is relieved by an angry Mr. Spock. When the navigator, below decks, announces to Beckwith he’s going to go straight and turn the dealer in, Beckwith murders him. There follows a court martial that finds Beckwith guilty, and Kirk and Spock lead a landing party down to a desolate planet to execute Beckwith by firing squad. Their immediate punitive plans are interrupted when they spot an ancient city high in the distant mountains. Because Star Fleet protocols prohibit executing criminals on inhabited worlds, they need to investigate this city before executing Beckwith, a “creature not even worth calling a man.”

Ellison’s version opens with a drug deal. The ship’s navigator, hopelessly addicted to an alien narcotic called the Jewels of Sound, purchases some of the stuff from a shady officer named Beckwith. We fade to the bridge, where the navigator, now high as a kite, nearly destroys the ship and is relieved by an angry Mr. Spock. When the navigator, below decks, announces to Beckwith he’s going to go straight and turn the dealer in, Beckwith murders him. There follows a court martial that finds Beckwith guilty, and Kirk and Spock lead a landing party down to a desolate planet to execute Beckwith by firing squad. Their immediate punitive plans are interrupted when they spot an ancient city high in the distant mountains. Because Star Fleet protocols prohibit executing criminals on inhabited worlds, they need to investigate this city before executing Beckwith, a “creature not even worth calling a man.”

Once the landing party reaches the city, they find it long abandoned except for a group of tall, ancient, bearded immortals who protect a portal-like time machine. After Beckwith flees through the machine while it is showing scenes of the Depression, the landing party beams back up, only to find that the ship is no longer the Enterprise but a renegade pirate ship called the Condor. This is when Kirk and Spock decide to go back down and go through the portal to try and change history back, while the rest of the landing party fight off the pirates. Once in 1930s America (Chicago in Ellison’s version), Kirk and Spock are chased by a xenophobic mob, steal some clothes, and then get jobs while waiting for Beckwith to appear. All this happens before we ever meet Kirk’s love interest Edith Koestler (she was changed to Keeler in a later version) in Act Three.

It’s a two-hour movie, in other words, not a 50-minute Star Trek script. And did I mention it was dark? After Kirk and Spock repair history by preventing Beckwith from pushing Edith out of the way of a truck, they return to the future; there, the “wise” (in fact, sadistic) Guardians assure Spock and the grief-immobilized Kirk that history has been repaired, but as a favor they request that they leave Beckwith with them, so they can punish him appropriately. They beckon Beckwith toward a pillar of light, and he “finds himself materializing in the heart of a sun.”

An execution that goes on forever and ever, for the Guardians have altered their machines so that Beckwith is caught in a time-Mobius. An interlocked time-phase that puts him into the heart of a blazing inferno just long enough to die, then snaps him out to a moment before he died, then puts him back then takes him out, over and over and over and over…

Yeah. It’s a really angry story. Ellison was a famously angry man. (Writer Nat Segaloff titles his biography of Ellison A Lit Fuse.)

The script Ellison delivered after Roddenberry’s requested cuts and changes simplified things a little—for instance, the court martial and firing squad from the treatment were eliminated in favor of Beckwith just fleeing to the surface—but the changes were not sufficient. Thus, Roddenberry had his writing staff—Steven Carabatsos, Gene Coon, and Dorothy Fontana—perform a series of rewrites that greatly simplified Ellison’s story. Beckwith was eliminated and an accidentally drugged McCoy became our history-altering MacGuffin. The Guardians of the time portal were eliminated and the portal itself became sentient, saving further on cost. The scene where the landing party beams up to the Condor and Yeoman Rand fights to hold the pirates at bay, was cut. Scenes showing a fascist demagogue stirring up hate in the streets and an employer’s racist treatment of Spock (passing himself off as a “Chinee”) were also cut. They also eliminated other, moving but strictly extraneous scenes and characters, including one involving a legless veteran of the Battle of Verdun named Trooper—more on whom below.

Apart from just simplifying (and way lightening up) Ellison’s sprawling story, the rewrites clarified and strengthened the narrative in crucial ways. In Ellison’s original version, Spock merely convinces Kirk that Edith must die because of supposition on his part that her peace movement might alter history by delaying the U.S. entry into WWII. Fontana, the unsung script doctor and secret heart of much of Star Trek, added the contrivance of a radio tube mechanism whereby Spock is able to use his tricorder to actually view news headlines from the original and the altered timelines, thereby convincing Kirk (and the audience) that, as he repeatedly says, “Edith Keeler must die.” This simple, elegant plot device is crucial to understanding and being compelled by the story.

I’m hardly the first to say that, even though Ellison’s teleplay is beautifully written and also contains the most badass scene ever written for Yeoman Rand*, it’s not Star Trek. It is unnecessarily sprawling—way too sprawling for an hour-long show. Whatever we might think of moralistically bowdlerizing realities (even on future starships) like drug-dealing and addiction, or the dangers of fascism, it reads less like an installment of the essentially utopian future of Roddenberry’s series than like a stand-alone film script. The logical and compassionate Spock’s repeated epithets about Depression-era Earthers (“savages” and “barbarians”) do not compute. Nor does it seem realistic that Kirk would be willing to let his beloved Edith die simply because Spock persuades him she might change history a certain way, based on cryptic hints provided by the ancient Guardians of the portal. There needs to be something concrete, and the viewer needs to see on Spock’s amped-up tricorder those conflicting headlines (“SOCIAL WORKER KILLED” and “F.D.R. CONFERS WITH SLUM AREA ‘ANGEL’”) as well as scenes of Hitler’s rallies, to be really sold on the necessity of letting history resume its former shape through the sacrifice of Edith. The mad-scientist contrivance of radio tubes—made as Spock memorably says, from “stone knives and bearskins”—is just the ticket.

I’m hardly the first to say that, even though Ellison’s teleplay is beautifully written and also contains the most badass scene ever written for Yeoman Rand*, it’s not Star Trek. It is unnecessarily sprawling—way too sprawling for an hour-long show. Whatever we might think of moralistically bowdlerizing realities (even on future starships) like drug-dealing and addiction, or the dangers of fascism, it reads less like an installment of the essentially utopian future of Roddenberry’s series than like a stand-alone film script. The logical and compassionate Spock’s repeated epithets about Depression-era Earthers (“savages” and “barbarians”) do not compute. Nor does it seem realistic that Kirk would be willing to let his beloved Edith die simply because Spock persuades him she might change history a certain way, based on cryptic hints provided by the ancient Guardians of the portal. There needs to be something concrete, and the viewer needs to see on Spock’s amped-up tricorder those conflicting headlines (“SOCIAL WORKER KILLED” and “F.D.R. CONFERS WITH SLUM AREA ‘ANGEL’”) as well as scenes of Hitler’s rallies, to be really sold on the necessity of letting history resume its former shape through the sacrifice of Edith. The mad-scientist contrivance of radio tubes—made as Spock memorably says, from “stone knives and bearskins”—is just the ticket.

As Fontana later revealed, one transformation in the story was not due to rewriting but to a comical misreading. Ellison’s ancient city was, like its Guardians, like something out of Tolkien—an ethereal vision of spires in the high mountains. Ellison had even described it as full of “rune stones.” The director of the art department, however, who admitted reading it after a couple drinks, did not know what “runes” were and, when he consulted a dictionary, happened on the word “ruins” and decided that that must be what Ellison intended. So the city in the filmed episode became an ancient, ruined city—an anachronistic (but now iconic) mix of broken Doric columns and the distended bagel-shaped Guardian of Forever.

Ellison hated it.

Success Has Many Parents

It is always easy to laud the solitary genius writer and fault the producers when things go wrong in Hollywood, but it is harder to acknowledge that Hollywood’s successes often arise from the same process. As Leonard Nimoy diplomatically puts it in a statement about Ellison’s script, “Success has many fathers. Failure is an orphan.” Fathers and mothers. The rewrites by Carabatsos, Coon, Fontana, and ultimately Roddenberry himself took Ellison’s great core premise and made it even better by stripping it of what was inessential and amplifying the love story at its heart. They also, it must be said, made it affordable—they made it possible to make the episode. Besides being too long, Ellison’s script had called for large crowds, glimpses of a mastodon rampaging through the Pleistocene, a pirate ship in orbit, and many more locations and characters. The success of the episode, and indeed its very existence, really was the product of a collaborative effort … and even happy accidents like the drunk art director thinking “rune” meant “ruin.”

Ellison was never able to see it that way … at least not consciously. He was already used to producers changing his scripts, and on other shows had opted to use the name “Cordwainer Bird” to disown the ones he felt were butchered. That name honored Paul Linebarger’s nom de plume Cordwainer Smith, while giving the “bird” to the producers who ruined his work. Fontana’s naming of the super-stimulant that drives McCoy mad, “Cordrazine,” was clearly a preemptive acknowledgment that Ellison would probably react badly to how she was changing his work. (Viewers should thus understand McCoy’s Cordrazine-crazed “Murderers! Assassins!” as Fontana’s affectionate parody of Ellison’s imagined reaction to her script-doctoring.)

Ellison was never able to see it that way … at least not consciously. He was already used to producers changing his scripts, and on other shows had opted to use the name “Cordwainer Bird” to disown the ones he felt were butchered. That name honored Paul Linebarger’s nom de plume Cordwainer Smith, while giving the “bird” to the producers who ruined his work. Fontana’s naming of the super-stimulant that drives McCoy mad, “Cordrazine,” was clearly a preemptive acknowledgment that Ellison would probably react badly to how she was changing his work. (Viewers should thus understand McCoy’s Cordrazine-crazed “Murderers! Assassins!” as Fontana’s affectionate parody of Ellison’s imagined reaction to her script-doctoring.)

Despite the extensive rewrites, Roddenberry begged Ellison not to use his nom de plume on this episode. The success—indeed, survival—of his bold new series depended on the high-caliber names he was bringing to the project. In fact, the producer had already elicited Ellison’s aid in a letter-writing campaign to “save Star Trek.” It has been argued that it was the success of “City” specifically that led to the renewal of the show for a second season. Thus, Ellison’s script, and his name, became inextricably entangled with Star Trek and its success.

While his initial experience was certainly frustrating, Ellison’s ire mainly grew over the subsequent decades when, at Star Trek conventions and in interviews, Roddenberry persisted in saying that the rewrites of “City” were necessary because Ellison’s original script was poor and that “he had Scotty dealing drugs”—both of which were demonstrably false, as anyone reading the draft can attest. Roddenberry’s lies over the years helped turn Ellison’s entanglement with Star Trek and with everyone’s favorite episode into a kind of festering wound: It became a dark sun, one that he couldn’t walk away from.

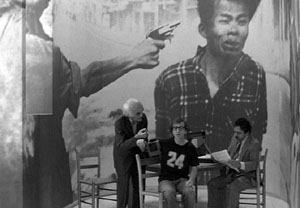

A fixture at Trek conventions and friend of many of its cast, Ellison’s grievance over Roddenberry’s unprofessional behavior and the original script of “City” that might have been—which he never stopped asserting was far superior to what was filmed—became part of the Trek myth. It was eventually published, along with Ellison’s incendiary rant and supporting essays by Nimoy, Fontana, and other Trek staff and cast, in 1995. Then in 2014 a comic series was made based on it, with gorgeous art by J. K. Woodward and covers by Juan Ortiz and Paul Shipper.

Thus, Ellison’s name came to be indelibly associated with the show. And arguably, at least for the wider public, it may be “City on the Edge of Forever” that Ellison is best known for. It is certainly what I knew him best for, even before I was aware of any of this saga, and I had even read a lot of his other fiction as a teen. All his fiction is outstanding, but “City” is fairly or unfairly regarded as one of his masterpieces.

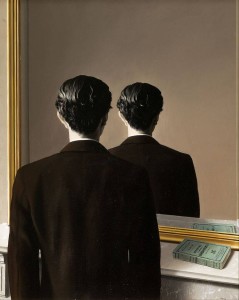

Here’s the thing: I think this big existential/creative clusterfuck, this big unfolding train wreck having to do with authorship and counterfactuals—what-ifs having to do with what he perceived as the ruination of his script, the “show that might have been,” and his good name appearing on what was really a collective creative effort—are precisely what his original script of “City” is about. In that story, he was vividly precognizing the “counterfactual neurosis” he suffered after it was rewritten and aired on April 6, 1967.

Mattering in the Time Flow

James Gleick argues in his book Time Travel that the SF premise of traveling back in time and undoing past mistakes is a way of dealing with trauma and regret. (“Regret,” he writes, “is the time traveler’s energy bar.”) The psychoanalytic term for regret and the counterfactual fantasies that repair our regrets is “castration.” That term is not just (or mainly) about lost genitalia. It is about being and nonbeing, having and losing, and fundamentally indeterminate there/not-there impossibility around which our desires and wishes revolve. The inner life of the neurotic is, one way or another, a confusing landscape of superimposed counterfactuals, “what ifs” and “what if nots” hovering over everything.

As I argue in Time Loops, life’s castrations—episodes in which we gain something despite a loss, or lose something despite a gain—are precisely what the precognitive (i.e., time traveling) unconscious focuses on.

As I argue in Time Loops, life’s castrations—episodes in which we gain something despite a loss, or lose something despite a gain—are precisely what the precognitive (i.e., time traveling) unconscious focuses on.

Ellison’s script centers on a counterfactual situation involving the destruction (vs. rescue) of something pure and beautiful and innocent. Kirk, who has fallen in love with the do-gooder activist Edith, must override his urge to stop Beckwith from pushing her out of the way of an oncoming truck … thus restoring history and returning the Enterprise to that future sky, so our heroes can go home. In other words, the life of this innocent beautiful pure thing must be taken or mangled so that others may live and that history must resume the shape that it already has.

It is interesting, first of all, that key characters cut from Ellison’s story have a curious there/not there quality even in his script. First, it seems significant how much deal—bizarrely too much—Ellison’s story makes of the erasure/obliteration of the “evil” character Beckwith, who was replaced by the temporarily Cordrazine-addled McCoy in the filmed version. It’s like the script’s MacGuffin was written to disappear, first to be executed on the most desolate planet imaginable—it is described as being so lonely and hopeless in the dead of intergalactic space that the ship’s blinds are drawn to keep the crew from having to view it (seriously!)—and then at the end to be condemned to infinite deaths in the heart of a sun by the “wise” Guardians. They keep bringing him back only to destroy him again, and again, and again.

Careful readers of the original script will note an uncomfortable paradox about Beckwith and his punishment: Despite his depravity, it is Beckwith whose human impulse is to rescue Edith at the climactic moment of the story as Ellison told it: Impulsively, he rushes to save her as a truck barrels down on her. It’s not Kirk’s love for Edith that changes the past, in other words—an obvious premise for a lesser writer—but the angry, drug-dealing murderer. But with Kirk and Spock now on the scene to make things right, Beckwith is thwarted from redeeming himself.** His flickering there/not there quality is like the larger counterfactual premise in which he is embedded, as well as the counterfactual history of Ellison’s script itself.

Something similar is true of Trooper, the legless survivor of the battle of Verdun, who appears at the beginning of the final act of Ellison’s script. “He is a man destroyed,” Ellison writes. “The light has gone out in the eyes, the mouth speaks a silent sadness. Disillusioned. He was the drummer boy who went to war, and came back to find no one needed him.” A sympathetic Kirk offers a couple dollars to Trooper, who is selling apples on the street from his wheeled cart, to let him know if he sees an armed, unusually-dressed man—Beckwith—appear in the neighborhood. Later, when Kirk and Spock are out walking at night, the veteran lets them know that a man fitting that description is nearby. Beckwith ambushes them and fires his phaser, vaporizing Trooper, and then gets away. Spock is concerned about Trooper’s death, noting: “Any death in this era that alters the sum of intelligence … alters time permanently.” Saddened, Kirk adds, “If he mattered in the time-flow.”

Later, after the accident that kills Edith and Kirk and Spock bring Beckwith back to the future, the time guardians announce, “Time has resumed its shape.” The first thing Spock asks is “What of the death of the cripple?” “He was negligible,” the wise Guardians reassure Spock.

So here again: The veteran’s mutilated condition, then his literal phaser-vaporization within the story and the assurance that history remains unchanged despite his death, both prefigure his “castration” from the story itself as it was eventually filmed.*** He is created to be unnecessary, disposable. Interestingly, the creators of the five-part comic version of Harlan Ellison’s The City on the Edge of Forever depicted Trooper as Ellison—honoring the writer by depicting him as its most poignant character.

Did Ellison’s precognitive brain grasp his own “castration” already as he was writing the character of Trooper? It is almost as if, in writing this character, Ellison was channeling his future regret at capitulating to his nemesis Roddenberry over the issue of his real name appearing on the title card—not standing up to him, in other words. For the famously feisty Ellison, this uncharacteristic capitulation to a producer may have been the crux of his counterfactual neurosis, the regret that drove him repeatedly into the past to make things right.

“Let Me Help”

Another interesting “counterfactual” difference between “City” as it might have been in Ellison’s version and as it “really was” in the televised version happens to center on my favorite bit of dialogue in all Star Trek. As Edith and Kirk are out walking in the evening, on a date, she notes how otherworldly he seems and his difficulty talking about his past. First, here’s how it appears in Ellison’s script:

EDITH: Sometimes you seem, well, disoriented, Jim, like a man fresh from the country.

KIRK: Iowa?

EDITH: Further away than that.

KIRK: “When night proceeds to fall, all men become strangers…”

EDITH: It’s true. Who said it, I don’t recognize it.

KIRK: Wellman 9. An obscure poet. Someday people will call his work the most beautiful ever known in the galaxy.

EDITH: That’s a lot of territory.

It’s poetic and beautiful—indeed, like much of Ellison’s script. But now read the scene as it appeared in the filmed version:

EDITH: Whatever it is, let me help.

KIRK: Let me help. A hundred years or so from now, I believe, a famous novelist will write a classic using that theme. He’ll recommend those three words even over I love you.

EDITH: Centuries from now? Who is he? Where does he come? Where will he come from?

KIRK: Silly question. Want to hear a silly answer?

EDITH: Yes.

KIRK: A planet circling that far left star in Orion’s belt…

I don’t know whether it was Coon or Fontana (or Roddenberry) who wrote this beautiful scene. But note how the final version not only manages to substantiate Kirk’s enigmatical nature in poetic terms (as Ellison did), but also makes the scene romantic (it slips “I love you” in there) as well as expressing what Spock will later say in starker terms: “She was right, but at the wrong time.” Kirk so much as tells Edith here that her own ethic of helping really is the way of the future—beyond mere love between two people. Kirk’s soliloquy becomes about Edith, in other words, instead of about himself: She is ahead of her time, just as much as he is out of his.

I don’t know whether it was Coon or Fontana (or Roddenberry) who wrote this beautiful scene. But note how the final version not only manages to substantiate Kirk’s enigmatical nature in poetic terms (as Ellison did), but also makes the scene romantic (it slips “I love you” in there) as well as expressing what Spock will later say in starker terms: “She was right, but at the wrong time.” Kirk so much as tells Edith here that her own ethic of helping really is the way of the future—beyond mere love between two people. Kirk’s soliloquy becomes about Edith, in other words, instead of about himself: She is ahead of her time, just as much as he is out of his.

My point is by no means that Ellison is a lesser writer than Coon or Fontana; he came up with the story, and he came up with the scene. It is simply that, like all good script revisions, a good idea is often refined further to become great. Behind many great writers there is also a great editor.

One has to wonder how much of the darkness and conflict in Ellison’s story, such as the dripping-with-cruelty punishment of Beckwith, or even the line about all men becoming strangers, reflected his own future conflicted feelings the “impossible” situation his script for “City” had put him in as an artist, because of the way his original creation differed from what audiences saw. Although the core premise and situation of “City” is every bit Ellison’s genius, much of what was shown in the episode was someone else’s. Besides the scene about “Let me help,” those “not Ellison” parts include also its most famous and memorable lines like “stone knives and bearskins” and “Edith Keeler must die.” Yet there’s Ellison’s name, in bold yellow letters right in the title credits. Taking (or being given) credit for other people’s good work is just as uncomfortable for a serious artist as having one’s words mangled or changed for the worse.

Having Our Cake…

The psychoanalytic essayist Adam Phillips almost sounds as if he has Ellison specifically in mind when he writes in his book Missing Out that “what was not possible all too easily becomes the story of our lives. Indeed, our lived lives might become a protracted mourning for, or an endless tantrum about, the lives we were unable to live.”

Again, Ellison maintained to the bitter end that his script was far superior to what Star Trek audiences saw that April night in 1967 (and endlessly on reruns in the 1970s), and he always promoted his script as the “City on the Edge of Forever” that should have been. But the thing about counterfactuals, about worlds and lives that might or should have been, is their disingenuousness. They are predicated on changing some nagging detail that bugs us, but without facing all the many consequences that would inevitably arise from making such a change in the real world. They are about having our cake and eating it too.

When you read Ellison’s bilious rants about Roddenberry and his Star Trek experience, his tirades against the talentless hacks who make life a living hell for writers, his scorn for idiot actors and the “bimbo queen” Joan Collins who tarnished his pure character Edith with her steamy reputation, the phrase “protests too much, methinks” comes to mind. Indeed, protests too much against a reality that really favored him in many ways.

There is no doubt Roddenberry lied and behaved unprofessionally, and for that, Ellison was right to feel aggrieved. But where is the acknowledgment that Star Trek and “City” were important and even central features in his life? Where is the acknowledgment that sometimes producers make the right decisions with scripts and that simplifying his sprawling story made it filmable? A reality of writing for the TV and film industry is that scripts are rewritten—and yes, sometimes badly. But the success of “City” as it was filmed—it won a Hugo award and was listed by many fans, cast, and crew as their favorite Trek episode—attest that the rewrites and other creative decisions made by Roddenberry’s team did not hurt this particular episode one bit. Quite the opposite.

The situation here is very similar to that of Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock: Had changes not been made to the original story, it either would not have been published or filmed, or it would have failed to gain a huge following. An unfilmed or poorly produced “City” would have failed to win the hearts and minds of audiences and thus would have failed to help sustain the ship of Star Trek into a second season … and then sustain ongoing interest of the fans. The same may be true had Ellison’s name not been attached to it. In either case, he would not have been associated—angrily or pleasantly—with the show and its enormous fan base and success over the next decades and for the rest of his life. (He was a regular feature at those Trek conventions.)

The disingenuous of Ellison’s later-life reflections on “City”—and I think, his deep-down awareness of their disingenuousness—are encoded, precognitively, right in the script’s basic “grandfather paradox” premise: that one person could change the past and that his shipmates could pursue him and undo or nullify his action. I mean, any ten-year-old can see, and does see on some level, that if the past has been altered to the extent that there’s no more Enterprise in orbit, there can’t be a Kirk and Spock and landing party standing there in front of the Guardian of Forever either. (This glaring problem was even more obvious in Ellison’s script, where the landing party beams back up to a different ship, now a pirate vessel manned by criminals; what are the odds that in the altered timeline an evil counterpart to the Enterprise just happened to be overhead?) Moreover, it is precisely while on a date with Kirk that the truck runs Edith over and that Beckwith (in Ellison’s version) or McCoy (in the final version) can be thwarted by our heroes from saving her.

The counter-history, in other words, depends on the “real” (or corrective/corrected) history at every turn. These problems stood out like sore thumbs in Ellison’s original script and would have made it that much harder to suspend disbelief. The rewrites hid them more effectively, but they are still there in the basic premise.

Our thoughts about how reality might be different unfold within this reality as it is. It is this easily forgotten fact that can serve as the “cipher key” of precognitive art, symptoms, and dreams.

Soldier

It is often time gimmicks of one sort or another that are the dead tip-off that some sort of real time loop by way of precognition may be occurring in an artwork as much as in a dream. It is interesting that while Ellison wrote a wide range of stories, and not only science fiction, he may be best known for three TV scripts about time travel: one that became an ongoing source of frustration into his future (“City”), another that resulted in a plagiarism suit, and a third that got associated with another filmmaker’s later work by association. All three involve future conflicts displaced or transposed into the past.

In 1964, Ellison adapted one of his short stories (“Soldier from Tomorrow”) for the series The Outer Limits. This episode, “Soldier,” starred Michael Ansara (whom Trek fans will recognized as the Klingon Commander Kang from “Day of the Dove”) as a future warrior named Qarlo Clobrigny who accidentally slips back through time to 20th Century LA, followed by an unnamed enemy soldier intent on finding and killing him. The opening scene of this episode (a post-apocalyptic battlefield with rayguns cutting through the night sky), and its basic premise (future warriors pursuing each other into the past), are virtually identical to James Cameron’s Terminator two decades later. When someone alerted Ellison to this similarity even before the film was released, he managed to get a look at the film in an early screening and sued the production company and distributor. Part of the evidence supporting Ellison’s claim of plagiarism was that Cameron had admitted in an interview with Starlog magazine that his story was inspired by some old Outer Limits episodes. A settlement was reached that included a credit to “the works of Harlan Ellison” in the home video version.

In 1964, Ellison adapted one of his short stories (“Soldier from Tomorrow”) for the series The Outer Limits. This episode, “Soldier,” starred Michael Ansara (whom Trek fans will recognized as the Klingon Commander Kang from “Day of the Dove”) as a future warrior named Qarlo Clobrigny who accidentally slips back through time to 20th Century LA, followed by an unnamed enemy soldier intent on finding and killing him. The opening scene of this episode (a post-apocalyptic battlefield with rayguns cutting through the night sky), and its basic premise (future warriors pursuing each other into the past), are virtually identical to James Cameron’s Terminator two decades later. When someone alerted Ellison to this similarity even before the film was released, he managed to get a look at the film in an early screening and sued the production company and distributor. Part of the evidence supporting Ellison’s claim of plagiarism was that Cameron had admitted in an interview with Starlog magazine that his story was inspired by some old Outer Limits episodes. A settlement was reached that included a credit to “the works of Harlan Ellison” in the home video version.

Cameron didn’t agree with the settlement, but it is obvious, watching “Soldier,” that his film did borrow from it (perhaps unconsciously). Could it also be the case that “Soldier” was precognitively inspired by Terminator—or rather, by Ellison’s uncomfortable encounter with that film—two decades hence? I find it odd that, here again, a story involving time travel, centering on a clash between two mighty foes chasing each other into the past, also resulted later in hard feelings between Ellison and a bigshot director that pertained directly to questions of originality and authorship.

Time travel stories are stories about origins. The linguist who studies Qarlo and takes him into his home determines that he has no family—no parents (he was, he reveals, raised in a “creche hatchery”). The unparented, the unborn, the truly original, with which we are led to sympathize, is pursued into the past by an enemy. Is this not a little like how Ellison might have seen Cameron’s apparent plundering of his 20-year-old “Soldier”?****

Even more uncannily, just as Trooper is depicted as legless in Ellison’s original “City” script, the pursuing unnamed future warrior in “Soldier” is trapped for most of the episode between times, struggling with his legs still in the future while his upper body is in the past. He literally struggles, legless, to free himself from his limbo throughout the episode.

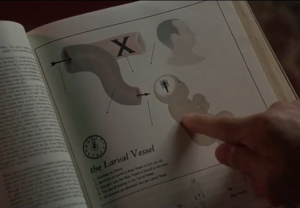

People who are vaguely aware of Ellison’s legal wrangling around Terminator sometimes confuse or conflate “Soldier” with another, even better (and stranger) Outer Limits episode Ellison also penned in 1964, called “Demon with a Glass Hand.” This episode is about a mystery man named Trent, played memorably by Robert Culp, who is pursued to 20th Century Los Angeles from the far future by alien Kaibans, bent on exterminating the last survivor of the human race. Trent is fitted with a glass hand, a computer whose memory is contained in missing fingers that he must obtain from the Kaibans who are pursuing him. In the end, having finally recovered all his fingers, the computer reveals that he himself is an android whose torso contains the memory of the entire human race on a copper wire—he must wait 2000 years for their memory to be reconstituted.

The possible confusion with the Terminator story here is the role of the hand—recall that Terminator 2 is premised upon the attempt to back-engineer technology recovered from the arm of the original robot assassin left behind in the past. But what a viewer of “Demon” today will be stunned by is the familiarity of the setting: The action takes place in the Bradbury Building in Los Angeles, which is where the climax of Blade Runner also takes place. Watching “Demon” now is like a weird B&W déjà vu, “revisiting” this gorgeous Victorian building with its wrought iron railings and its elevators. Like in Blade Runner, some of the action takes place in its attic and on its roof. And like Blade Runner’s climactic scenes with a fixation on hands that are mangled or maimed (Deckard’s broken fingers, Roy Batty’s self-impalement), “Demon” also centers on images of Trent’s glass hand that is disturbingly incomplete, missing some of its digits.

The possible confusion with the Terminator story here is the role of the hand—recall that Terminator 2 is premised upon the attempt to back-engineer technology recovered from the arm of the original robot assassin left behind in the past. But what a viewer of “Demon” today will be stunned by is the familiarity of the setting: The action takes place in the Bradbury Building in Los Angeles, which is where the climax of Blade Runner also takes place. Watching “Demon” now is like a weird B&W déjà vu, “revisiting” this gorgeous Victorian building with its wrought iron railings and its elevators. Like in Blade Runner, some of the action takes place in its attic and on its roof. And like Blade Runner’s climactic scenes with a fixation on hands that are mangled or maimed (Deckard’s broken fingers, Roy Batty’s self-impalement), “Demon” also centers on images of Trent’s glass hand that is disturbingly incomplete, missing some of its digits.

Here again, is sci-fi causality simply proceeding in the usual, billiard-ball direction, with a more modern filmmaker (Ridley Scott in this case) paying homage to a brilliant predecessor? Or is there a degree of bidirectional causality going on too? Did Ellison’s time travel scripts fractally reflect his later mixed feelings over the role of those scripts in his life, which by then appeared as forgotten ghosts haunting big science fiction blockbusters?

There is no way to answer these kinds of questions definitively, and we cannot ask Ellison about it because he passed away in June of last year. But in my experience with dreams and writing, time travel is a conveniently gimmicky way for the precognitive unconscious to package an idea or a feeling that comes from one’s future. I suspect Ellison, at least in these famous time-travel stories, was drawing on his future conflicts with other artists as well as with his future self, as the source and wellspring of his creativity.

2+2=4

A psychoanalyst professor of mine used to relate a piece of professional lore that applies to a conflicted person like Ellison, or to anyone insofar as we are conflicted: A normal person says “two plus two equals four.” A psychotic person says “two plus two equals five.” But a neurotic person says “two plus two equals four … and I hate it.” The moment of cure in psychoanalysis is equivalent to becoming able to say that two plus two equals four without screwing one’s face into a grimace—an acceptance of reality as it is, without nursing the kinds of counterfactual fantasies that consume so much of our inner energy.

The Zen experience of “suchness” or tathata, is identical to this almost euphoric satisfaction of things being just as they are. In other words, nothing is different, but suddenly I don’t need to worry so much about it. I don’t need to mentally rummage in the past to correct things that can’t be fixed anyway. And I don’t need to stress out that my actions now might lead to a future that will compare unfavorably to one in my imagination.

The Zen experience of “suchness” or tathata, is identical to this almost euphoric satisfaction of things being just as they are. In other words, nothing is different, but suddenly I don’t need to worry so much about it. I don’t need to mentally rummage in the past to correct things that can’t be fixed anyway. And I don’t need to stress out that my actions now might lead to a future that will compare unfavorably to one in my imagination.

The Guardian of Forever in the famous, filmed version of “The City on the Edge of Forever” has its own way of pronouncing the psychoanalytic cure, or tathata, and one that is even more poetic: Upon Kirk, Spock, and McCoy’s return to the future, it announces: “All is as it was before.”

All is as it was before. It is a deeply reassuring statement to the rest of the landing party, who barely noticed Kirk and Spock were gone (from their vantage point, they had only been away a minute or two) and now find the Enterprise hailing them from orbit. It is not totally reassuring to Kirk, smarting (to put it mildly) from the pain of losing Edith Keeler. But restoring time to its normal shape is often painful, even while it is freeing—regaining one’s “legs,” so to speak, or one’s ship. You are free to move on.

It enables you to say, as Kirk does at the end of “City”: “Let’s get the hell out of here.”

Personal Postscript

I’ve been putting off writing about “City” for a long time. It is such a powerful myth in my own life that I am almost superstitious about it. It initially aired exactly one month after my birth, and it is indelibly etched in my brain from a childhood steeped in Star Trek reruns. Over the years I have had significant, powerful dreams that centered on motifs and objects from this episode. These dreams were not about that episode—why would evolution equip us with a brain that obsessed over old television shows?—rather, like all dreams, they were using its elements and themes as symbols to represent concerns in my life then and even, I think, thoughts from my future. Those thoughts including some of the ideas about time, time loops, and counterfactuals that have been obsessing me in the past year or so.

Another, equivalent way of looking at it is that these present thoughts—even this blog post—shaped me in my past, even decades ago, via those dreams.

Another, equivalent way of looking at it is that these present thoughts—even this blog post—shaped me in my past, even decades ago, via those dreams.

For example, Spock’s radio-tube contraption as a kind of “counterfactual detector” has been a recurring theme in my dreams over the years. It is often conflated or mashed up with an old tube amp I purchased at a music store on Pearl Street in Boulder, Colorado, in my freshman year of college and very regretfully swapped for a less cumbersome solid-state one a couple years later. (Both amps are now long gone from my life.) This “amp that might have been” (always threatening to overheat, as Spock’s does) has reappeared in dreams over the years in connection with counterfactual situations, sometimes with a “time gimmick” involved. In one dream, for example, I used the device to play a heavily distorted version of the Doctor Who theme song. That too was years before I knew I’d be devoting a significant chunk of my life to the study of time and our mental travel through it.

In another powerful dream from 1995, I made an initiatory journey through a stone loop in a wild landscape toward a plaster mastodon (ancient bones in a cast), prefiguring by more than two decades my parapsychological interest in time loops and the autobiographical project of dream paleontology … and possibly even prefiguring my recent reading of Ellison’s teleplay, which includes a mastodon appearing in his time portal.

The lesson of time travel is that the past cannot be changed from what already is, but that it can be (and always was) created by us in the present. As we move through life, especially as we become increasingly conscious of our four-dimensional nature (our “long body”), we can ongoingly unearth evidence of how our experiences and thoughts now contributed to who we were and what we did then. This mindblowing perspective on our biographies will increase as we become more culturally comfortable with retrocausation. With that comfort will come the setting aside of security blankets like “many worlds” and multiverses that let us have the cake of our exquisite regrets (like foolishly getting rid of that totally sweet tube amp) and eat them too.

NOTES

* I’m obviously somewhat biased in favor of “City” as it was filmed, but one regret about the version that might have been is that Ellison had written such a good scene for Yeoman Rand, fighting to keep the pirates at bay aboard the renegade ship Condor. Grace Lee Whitney, who played Rand, had already been let go from the series by the time this episode shot, however. In a counterfactual history where Whitney was still with the series, her role would probably have been reduced to the one Nichelle Nichols’ Uhura had to play in the filmed version, delivering it’s most cringeworthy line: “Captain, I’m frightened.” The gender backwardness of the series must be acknowledged.

Also, the circumstances around Whitney’s dismissal cast even poorer light on Roddenberry, and may even have added an unspoken dimension to Ellison’s anger at Roddenberry over the ensuing decades. What really happened has been the subject of much controversy, but the general picture that emerges was the kind of thing that has become all too familiar in our Me Too era: Whitney claims she was raped by one of the producers—some figure, from hints in her memoir, that it was Roddenberry himself. Almost immediately after this happened, Roddenberry allegedly capitulated to pressure from the studio to cut her character due to the perception that she made Kirk seem less available. Whitney was devastated, but claimed that she ultimately forgave Roddenberry. Whitney returned to the franchise for roles in several of the films.

According to his biographer Nat Segaloff, Ellison and Whitney had been dating in the years before he wrote his episode for Star Trek. Ellison later contended that the “studio pressure” to dispense with the character of Yeoman Rand was really pressure from Majel Barrett (Nurse Chapel), who was at that point having an affair with Roddenberry and was jealous of Whitney.