The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

Scarabs & the ‘Send’ Button: Synchronicity as Misrecognized Psi

During the weeks I was researching my previous post on 9/11 and premonitions of trauma, I had a very powerful, uncanny experience that contained, in miniature, all of that post’s themes. It began with an unusually bad day at work, where I’d felt extremely guilty over a group email I had sent to coworkers that, because of poor word choice, could have been construed as insulting to one of the people cc-ed on it. After I hit “Send,” I started to stew about it, feeling embarrassed and angry at myself for my lack of tact. This was near the end of the workday, and I felt bad about it all the way home on the metro.

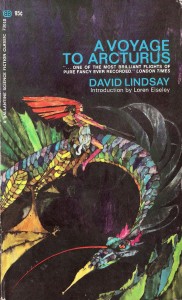

Awaiting me on the doorstep was a brown paper package containing a book I’d ordered more than a week earlier and forgotten about. I order lots of used and out-of-print books on Amazon and eBay, which often take weeks to arrive, so I’ve usually forgotten them by the time I get them. This one happened to be by a former professor of mine in graduate school, on the subject of paradoxes. What stunned me was the return address on the package was a woman with the same very unusual surname as my professor, who (I assumed) could only be his wife—her Amazon Seller name was different so I’d had no idea it was her. This was obviously a remaindered copy of her husband’s long-forgotten book.

The cosmos seemed to be serving up my guilt to me on a platter. But in fact, it was just serving me an emotional time loop I didn’t immediately fathom until I delved into the matter.

This by itself would not be so amazing, but what was stunning was that I had for 25 years harbored regret over a group bulletin-board message I had sent to fellow students and faculty in my graduate department, in which, through tactlessness and poor word choice, I feared I inadvertently hurt the feelings of this woman, my professor’s wife. In other words, my current emotional situation about a work email a couple of hours earlier that day was a precise mirror image of a situation two and a half decades ago involving precisely the person who had mailed me this book on paradox.

Tactlessly hurting people in emails or bulletin board messages is not the sort of thing I do commonly—in fact, I couldn’t think of another instance in those 25 years in which quite this same thing had occurred. This book of my old professor, arriving on my doorstep, was like a bizarre short circuit between two highly unusual events a quarter century removed in time.

… Or at least, that’s how it seemed, until I took a closer look.

Temporal Bias and Beetlemania

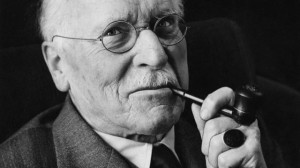

The book on my doorstep was very much like the most famous object in the annals of meaningful coincidence, the scarab beetle that tapped on the window of Carl Jung’s Zurich office, described in his book Synchronicity:

A young woman I was treating had, at a critical moment, a dream in which she was given a golden scarab. While she was telling me this dream, I sat with my back to the closed window. Suddenly I heard a noise behind me, like a gentle tapping. I turned round and saw a flying insect knocking against the window-pane from the outside. I opened the window and caught the creature in the air as it flew in. It was the nearest analogy to a golden scarab one finds in our latitudes, a scarabaeid beetle, the common rose-chafer (Cetonia aurata), which, contrary to its usual habits had evidently felt the urge to get into a dark room at this particular moment. I must admit that nothing like it ever happened to me before or since.

We tend to think, when these things happen, that some higher organizing principle or intelligence has prearranged these coincidences in our life to act as a kind of sign. That is precisely how I felt as I opened the package from my professor’s wife. I could imagine her putting the book in the brown envelope, penning my address on the side, and muttering “Here you go, asshole” … and that this was part of a larger cosmic design to serve my own tactless or thoughtless behavior up to me on a platter. Frequently of course, synchronicities have a positive feeling, like God winking or giving us the thumbs up—or in Jung’s case, providing confirming evidence of a deeper mystery about the mind and cosmos.

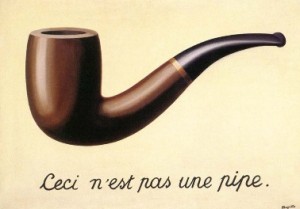

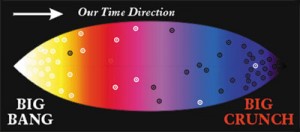

But as I argued in my last post, there’s a much simpler explanation for many (albeit not all) such occurrences, so long as we grant that some kinds of information—namely, our own complex emotional reactions to future traumatic situations—can travel backward in time and influence us in the present, if only on an unconscious level.

Our own complex emotional reactions to future traumatic situations can travel backward in time and influence us in the present, if only on an unconscious level.

Much laboratory evidence has been gathered, particularly by Daryl Bem and Dean Radin, for emotional responses to imminent events. This could well explain the most common type of “synchronicity”: thinking of a certain person and then receiving a call or email from them, or thinking of an unusual object and then seeing one. We naturally interpret the present as caused by the past, because the bulk of causality seems to flow in a forward direction, and this is also how we naturally interpret the flow of our own thoughts. Thus, a causal heuristic, or temporal bias, causes us to habitually overlook natural forms of precognition and presentiment and thus misconstrue their effects as uncanny coincidences: Having a thought about our old friend X, which we naturally assume arose from our ordinary, forward train of thought, may actually have been stimulated by a presentiment or premonition of their imminent call.

J.W. Dunne noted in An Experiment with Time that this bias to interpret the present in terms of the past causes us to miss the precognitive elements in our dreams as well. Even people who assiduously record and interpret their dreams (like me, for decades, until reading Dunne’s book) rarely go back to those records in the future, in any systematic fashion, to identify possible precognitive material. Yet when you do—specifically over the next 1-2 days—a certain amount of precognitive stuff becomes quite evident. (When you take the further step of free-associative interpretation on bizarre symbols, even more “future” material turns up.)

It turned out that this principle is actually the only possible explanation for my own ‘synchronistic’ experience … and I argue it even explains Jung’s scarab much better than Jung’s own theory.

An Ass Out of You and Me

Late on the evening I received the book in the mail, I rose from bed—I was unable to sleep in my weird excitement over the coincidence—and I used my most powerful Google-fu to verify that the woman who had sent my package was indeed my old professor’s wife. Lo and behold, I discovered she was not. She was, probably, an in-law, married to another man with the same last name—a man not too far in age from my old professor, and thus likely his brother or cousin (not a son). (They had to be related, as there is no conceivable other reason why they would have possessed an unread copy of this very specific academic text other than that they had been given a copy by the author—like I said, the author’s surname is very unusual and the topic is abstruse).

In other words, my recollection of my 25-year-old blunder was triggered by a false assumption that the person who packaged up this book was the person I’d slighted all those years ago—and we all know what happens when we assume. But here’s the clincher: At work the following day, I re-read the email I had sent to my coworker, the one I had stewed over. On rereading, I realized that my words were not actually as tactless as I’d thought, and that I’d really had little cause to get as worked up as I had. The person in question harbored no ill will toward me. Why then had I emotionally overreacted?

Indeed, my anguish over that email was one of the weirdest parts about the whole experience—I’m ordinarily a pretty calm, Zen guy, but I was in a very strange emotional state by the time I arrived home, and the name on the package made my hair stand on end from the seeming coincidence … yet there was, in fact, as my late-night googling later revealed, objectively no coincidence. I had jumped to a wrong conclusion, but it had triggered a very real emotional response.

Indeed, my anguish over that email was one of the weirdest parts about the whole experience—I’m ordinarily a pretty calm, Zen guy, but I was in a very strange emotional state by the time I arrived home, and the name on the package made my hair stand on end from the seeming coincidence … yet there was, in fact, as my late-night googling later revealed, objectively no coincidence. I had jumped to a wrong conclusion, but it had triggered a very real emotional response.

The simplest explanation for this apparent synchronicity is thus the “retrocausal” one I outlined in my last post as operating in the case of 9/11, the Titanic, Mark Twain’s dream, and the career of Elizabeth Fraser of Cocteau Twins. My awakened anguish over a reminder of my 25-year-old regret over a social blunder echoed backward a few hours to a structurally similar situation, the email at work, and caused an exaggerated emotional reaction that I naturally and logically misattributed to that email. When I got home and found the book and saw who (I mistakenly assumed) it was from, I was blown away by the coincidence: The cosmos seemed to be serving up my guilt to me on a platter. But in fact, it was just serving me an emotional time loop I didn’t immediately fathom until I delved into the matter.

In other words, there was no coincidence, no synchronicity. There was however an “acausal connecting principle” in the form of my powerful and conflicted emotional response: reawakened pain and regret coupled with a kind of excitement—a powerful emotional melange I have called, using Lacan’s term, jouissance.

Synchrosplaining and Psi-sploitation

The exact same process explains Jung’s scarab story. To see why, we need to return the scarab to its proper owner.

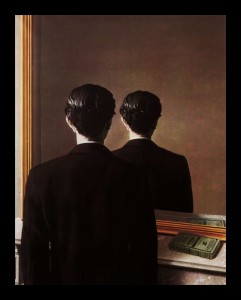

It is sort of natural to read the uncanny account as centering on Jung himself—it is implicitly “his” synchronicity because, well, he wrote about it, and it involves simultaneously hearing his patient’s dream story about a scarab and responding to the tapping of an actual scarab at his office window and catching it. Even though it is outside his direct control, Jung thus manages to claim and capitalize on the moment, offering the beetle to his patient (just as she had dreamed) at the precise moment she needs this gesture to break her from her rigid causal modes of thinking. Claiming this moment as a therapeutic intervention, Jung thereby presents himself as a kind of heroic modern shaman or psychomagician.

Looking at it this way, as centered on Jung, the event truly would have to be “acausal,” as there is no way to causally explain the coincidence of hearing someone else’s story about a scarab and a real scarab happening to appear at that precise moment. But the simplest explanation is really that it’s not about Jung or his experience at all: His female patient had precognitively dreamed about the scarab, associating it with her impending therapeutic epiphany. Instead of being “Jung’s synchronicity,” a far simpler explanation is that it was his patient’s precognitive dream, and he played merely a supporting, not starring, role in it.

Looking at it this way, as centered on Jung, the event truly would have to be “acausal,” as there is no way to causally explain the coincidence of hearing someone else’s story about a scarab and a real scarab happening to appear at that precise moment. But the simplest explanation is really that it’s not about Jung or his experience at all: His female patient had precognitively dreamed about the scarab, associating it with her impending therapeutic epiphany. Instead of being “Jung’s synchronicity,” a far simpler explanation is that it was his patient’s precognitive dream, and he played merely a supporting, not starring, role in it.

Jung’s spinning of this event, which is dare I say ‘archetypal’ in the lore of the paranormal, as “synchronicity” (as opposed to merely an interesting case of ESP) reflects typical male egotism on his part—appropriating his female patient’s remarkable psi experience and turning it into something much bigger and more profound, something flattering to his (male) genius, because only he is able to grasp and explain it. Jung exploited his patient’s psi, in other words, to support his own nascent theory about how the the inner and outer worlds are linked via his pet concept of archetypes.

Jung’s overreach here may reflect a larger blindness that we all share—not only a temporal bias but also an egotistic bias: our natural habit of interpreting coincidence as the big universe harmonizing with our own little life story. The cosmos winking at us, giving us the thumbs up (or thumbs down, in my case), or at least taking an active interest in us, is a much more ego-gratifying interpretation than the notion that psi is just a natural function that operates all the time in our lives and that produces weird effects because we don’t recognize it. It would be like not believing in farts and instead concocting an elaborate theory to explain those funny smells that every so often waft through the room.

Paradoxically, it is often our ego that prevents us from including the knower in the known … although in the case of the synchronistic scarab, the knower was Jung’s patient, not Jung.

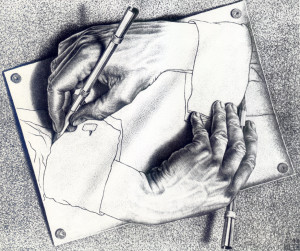

Prophetic Jouissance

There is a recursive, self-similar or self-referential quality about many meaningful coincidences and premonitory or precognitive dreams. In Jung’s case, the scarab happened to be a symbol of rebirth and awakening, so within his (or really, his patient’s) archetypal encounter was an archetype about awakening to archetypes. In my case, the book on my doorstep happened to be about insoluble paradox and contradiction as a creative force, and this fractally rhymed with the very idea that I had been writing about and that I am further developing here: the seemingly paradoxical or self-contradictory notion of time loops as an unconscious factor in thought, emotion, and dreams.

While I think Jung’s theory—that meaningful coincidences reflect an archetypal harmonization of objective events with our unconscious minds—could be an overreach, I do think perceived coincidence does play a crucial role. Because life is a “blooming buzzing confusion” of events and information, coincidences happen all the time and we only notice a fraction of them. Noticing coincidences is facilitated by believing they are significant. On an unconscious level, we probably all believe that; even Richard Dawkins must possess a superstitious unconscious. When we notice objective events that seem to reflect some inner thought, however trivial, this may amplify our reaction to whatever precipitated that thought, doubly so if we happen to derive intellectual or egotistical enjoyment from things paranormal and psychic and synchronistic. The ultimate effect of this enhanced enjoyment of coincidence may be a kind of feedback loop, in which the intensity of our emotional reaction quickly escalates, like a microphone placed too close to a speaker.

While I think Jung’s theory—that meaningful coincidences reflect an archetypal harmonization of objective events with our unconscious minds—could be an overreach, I do think perceived coincidence does play a crucial role. Because life is a “blooming buzzing confusion” of events and information, coincidences happen all the time and we only notice a fraction of them. Noticing coincidences is facilitated by believing they are significant. On an unconscious level, we probably all believe that; even Richard Dawkins must possess a superstitious unconscious. When we notice objective events that seem to reflect some inner thought, however trivial, this may amplify our reaction to whatever precipitated that thought, doubly so if we happen to derive intellectual or egotistical enjoyment from things paranormal and psychic and synchronistic. The ultimate effect of this enhanced enjoyment of coincidence may be a kind of feedback loop, in which the intensity of our emotional reaction quickly escalates, like a microphone placed too close to a speaker.

This is what I meant in my previous post when I suggested that not only was Elizabeth Fraser channeling a presentiment of Jeff Buckley’s drowning death, but that the eventual recognition of the coincidence between her “siren” personal myth and that tragic event actually amplified its traumatic signal into the past, increasing its ‘gain.’ Fraser’s unconscious mind would have enjoyed the (consciously unspeakable, not to mention unrealistic) idea that her siren powers had actually been potent enough to lure an ex-lover to a watery grave, and this amplified the trauma’s uncanny shock, creating a very loud signal that she channeled into exquisitely beautiful music for two decades … in turn boosting the volume of the coincidence on learning of Buckley’s death, in turn intensifying the whole siren thing, and so on… This amplification of jouissance through the paradoxical effect of the time loop is what Lacanians call a “symptom.”

The same thing would have happened with Jung’s patient. Her therapeutic epiphany was a powerful, dreamworthy moment, but its dreamworthiness was boosted by the appearance of the scarab, which became the nucleus of her dream, and thus created the uncanniness when she related the dream to her doctor. The moment in Jung’s office was overdetermined because its signal had been amplified into the past. (Indeed there is maybe no better example of a Lacanian ‘symptom caused by its cure’ than this Jungian incident.) This shows clearly that a time loop may not only be self-canceling, as in the famous grandfather paradox … it could also be self-amplifying.

A time loop may not only be self-canceling, as in the famous grandfather paradox … it could also be self-amplifying.

In my Psi of Regret post I touched on some of the existential and moral ambivalence that prophecy automatically awakens and that acts as a mitigating force on our psychic potential. I think the prophetic jouissance I am describing here is possibly the most powerful and decisive factor—one that paradoxically amplifies precognitive effects at the same time as it pushes them outside of our purview, into the ego-saving and ego-gratifying realm of the “synchronistic,” where they are simultaneously more sublime and less practically useful. Synchronicity may thus be a concept that actually neutralizes our psi by keeping us from too closely examining its disavowed libidinal logic. Jung may have broken from Freud too soon.

In his TED talk, Jacques Vallee invokes Philippe Guillemant’s theory of “double causality” to explain synchronicities: Our intentions cause effects in the future that become the future causes of present effects. I am suggesting the operative term may not be intentions but enjoyment. The time-loop character may be precisely an amplifier of the enjoyment component in trauma that echoes backward in time (or that is simply non-obedient to time), as in disasters and deaths. Some part of us derives a benefit, experiences bliss, at whatever happens—even awful things. A wicked, suppressed, repressed part of us likes to think of ourselves as witches and shamans controlling larger cosmic and magical forces; this disavowed magical-thinking inner savage might actually be a synchromystic trickster in our lives, but perhaps also (if properly propitiated) an ally.

The concept of synchronicity, in other words, may be precisely a conceptual box to defend ourselves from the truth of our precognitive functioning, and thus it may be time to replace it with a better theoretical framework. The concept of jouissance as an atemporal and nonlocal phenomenon could not only help us understand precognitive and other psi effects better, it could also reveal new ways of capitalizing on forces that, for now, for most of us, remain very much in the dark or (apparently) outside our control.

I’ll develop this idea further in future posts.

Trauma Displaced in Time: Premonition, Synchronicity, and Enjoyment

On the morning of September 11, 2001, my alarm awoke me around 6:30AM and I did what I always try to do before dragging myself from bed: I rolled over, grabbed my notebook and pen, and jotted notes on whatever dream images I could recall from the night before. That morning I noted dreaming about driving past a pair of identical “mosques”—distinctly low, 1-story buildings, perfectly square in plan, with drab corduroy-like facades—on a street near where I grew up in Lakewood, Colorado. They were in exactly the site of an office building where, in real life (and about 30 years earlier) my father had briefly had his psychology practice, before moving his office to a nearby bank building.

I had never dreamed of “mosques” before, nor anything with Islamic overtones that I could recall. Islam was not on my radar. The only detail whose meaning I grasped at the time was the one-story-ness of the buildings (i.e., the opposite of tall buildings); my dreams have periodically featured “low buildings” as well as ruined towers that, I had figured out from a decade or more of psychoanalytic dream interpretation, mainly had a standard “castration” symbolism—stereotypical Freudian stuff, and not very remarkable. It was only in hindsight that I realized how the corduroy appearance of my dream “mosques” matched the distinctive corrugated facade of the towers that came crashing down that day.

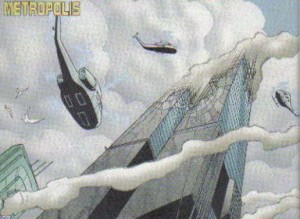

I’m hardly the only person to have dreamed of something plausibly connected to 9/11 in the days before the event. A quick internet search turns up numerous pages of more remarkable stories of vivid dreams and visions. Bonnie McEneaney, who lost her husband in the attack, recalls in her book Messages that her husband had been gripped for months by a certainty that an attack was imminent and that he was soon to die. And 9/11 ‘prophecies’ go well beyond such narratives that are necessarily biased by hindsight (and thus fail all scientific standards of reliability). The number of ominous-seeming prophetic artworks, images, etc. unmistakeably produced prior to the 9/11 attacks but seeming to depict them is rather staggering, as a quick Internet search also reveals.

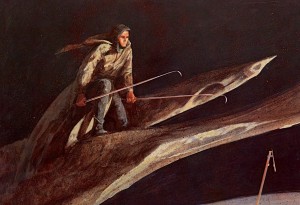

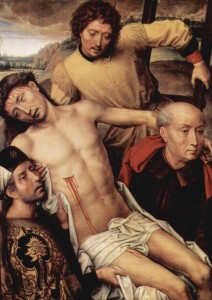

For example, issue #596 of The Adventures of Superman, released on September 12, 2001 (but obviously drawn and written sometime in the weeks immediately preceding the disaster), shows the towers smoldering after being attacked in a superhero conflict. The issue was promptly recalled by the publisher, DC Comics, making it now something of a collectors item. Even more uncanny is the bronze 1999 sculpture Tar Baby vs St. Sebastian by Michael Richards (below), in which the artist depicts himself as one of the Tuskegee Airmen, standing very erect (and building-like), being pierced by numerous planes. Could it have been inspired by a premonitory dream or vision of his own death in his studio on the 92nd floor of Tower One on 9/11?

For example, issue #596 of The Adventures of Superman, released on September 12, 2001 (but obviously drawn and written sometime in the weeks immediately preceding the disaster), shows the towers smoldering after being attacked in a superhero conflict. The issue was promptly recalled by the publisher, DC Comics, making it now something of a collectors item. Even more uncanny is the bronze 1999 sculpture Tar Baby vs St. Sebastian by Michael Richards (below), in which the artist depicts himself as one of the Tuskegee Airmen, standing very erect (and building-like), being pierced by numerous planes. Could it have been inspired by a premonitory dream or vision of his own death in his studio on the 92nd floor of Tower One on 9/11?

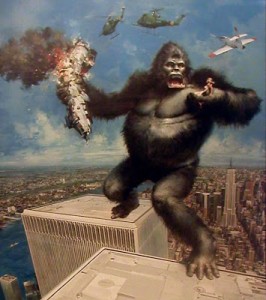

Any man who was a kid in the 1970s may also have been reminded, as the disaster unfolded that morning, of Dino DeLaurentis’s 1976 remake of King Kong, in which the giant ape scaled the then-new twin towers (instead of the Empire State Building) because they reminded him of a pair of rocks he had loved to climb back home on Skull Island. Sci-fi artist John Berkey’s publicity poster for that movie (bottom of this post), with its exploding planes, is eerie in hindsight—as are countless other images in ads, cartoons, or films showing the towers being attacked by or simply standing in ominous juxtaposition to aircraft, and these have of course fueled conspiracy theories about US government foreknowledge of (or involvement in) the attacks.

Any man who was a kid in the 1970s may also have been reminded, as the disaster unfolded that morning, of Dino DeLaurentis’s 1976 remake of King Kong, in which the giant ape scaled the then-new twin towers (instead of the Empire State Building) because they reminded him of a pair of rocks he had loved to climb back home on Skull Island. Sci-fi artist John Berkey’s publicity poster for that movie (bottom of this post), with its exploding planes, is eerie in hindsight—as are countless other images in ads, cartoons, or films showing the towers being attacked by or simply standing in ominous juxtaposition to aircraft, and these have of course fueled conspiracy theories about US government foreknowledge of (or involvement in) the attacks.

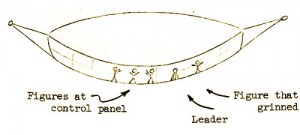

Perhaps the most amazing portent of the attacks, though—for me anyway—was Phillipe Petit’s tightrope walk between the still unfinished towers in 1974, as depicted in the documentary Man on Wire. As when the towers fell 27 years later, witnesses on the ground were shocked, awed, thrilled, and terrified, watching this French daredevil blithely balance on a cable 1,350 feet in the air that he had strung between the towers with the help of a bow-and-arrow and a couple accomplices. It is amazing to me, because it is as if the 27-year lifespan of the World Trade Center, that audacious symbol of American power and capitalism, was book-ended or framed by two highly symmetrical events: audacious aerial conquests, both pulled off with great stealth and ingenuity by foreigners who had trained extensively and in secret, for months, astonishing and frightening the crowds below who couldn’t believe their eyes.

A Night to Misremember

Skeptic Martin Gardner would probably have called any attempt to sift the “impossible” from the merely slightly improbable in the long list of “9/11 prophecies” misguided. In a book on the similarly uncanny predictions of the Titanic disaster, he writes that such problems are “not well formed”: “There is no way to estimate, even crudely, the relevant probabilities.” With the Titanic, as with 9/11, there were dreams and premonitions—or at least ones recollected after the fact. For example, in an excellent 1982 In Search Of episode, an elderly survivor, Eva Hart, who had been seven at the time, recalled that her mother had had a terrible premonition that their voyage would be fatal. Hart’s father indeed was lost with most of the other men aboard the ship, although she and her mother made it into to the lifeboats. Gardner lists other similar examples in his book.

But the most famous prophecy of the Titanic’s sinking—and Gardner’s main focus—is Morgan Robertson’s 1898 novel Futility, or The Wreck of the Titan, which appears to have foretold the disaster down to myriad “impossible” details, including not only the ship’s name (Titan), its tonnage and size, its passenger capacity, its insufficient lifeboats, the iceberg that hit it and where on the ship it struck, the exact location in the Atlantic where it sank, and even the month (April). These details seem amazing when presented in isolation, but Gardner shows that when you put them in context, some of the uncanniness dwindles. The Titanic’s name could have been pretty accurately predicted based on the names of the company’s other ships, for example. Fear of fatally hitting icebergs in the North Atlantic was a very real one at the time, and this would have been natural fodder for a writer of sea yarns. They typically occurred in spring, so April was a natural month to choose. And the idea of too-few lifeboats on a doomed ocean liner was also a pretty natural idea, and was widely used by other writers.

But the most famous prophecy of the Titanic’s sinking—and Gardner’s main focus—is Morgan Robertson’s 1898 novel Futility, or The Wreck of the Titan, which appears to have foretold the disaster down to myriad “impossible” details, including not only the ship’s name (Titan), its tonnage and size, its passenger capacity, its insufficient lifeboats, the iceberg that hit it and where on the ship it struck, the exact location in the Atlantic where it sank, and even the month (April). These details seem amazing when presented in isolation, but Gardner shows that when you put them in context, some of the uncanniness dwindles. The Titanic’s name could have been pretty accurately predicted based on the names of the company’s other ships, for example. Fear of fatally hitting icebergs in the North Atlantic was a very real one at the time, and this would have been natural fodder for a writer of sea yarns. They typically occurred in spring, so April was a natural month to choose. And the idea of too-few lifeboats on a doomed ocean liner was also a pretty natural idea, and was widely used by other writers.

In his book The Sublime Object of Ideology, Lacanian philosopher Slavoj Žižek takes this argument one step further. He notes that the disaster corresponded closely to the political-economic-cultural unconscious of the time, and for this reason took on an a weight of symbolic overdetermination that caused it to appear synchronistic in hindsight. Not only was the ship itself easy to predict in its dimensions and even its name, but some disaster or comeuppance befalling the blithe elite was also easy to anticipate. Žižek writes, “even before it actually happened, there was already a place opened, reserved for it in fantasy space. It had such a terrific impact on the ’social imaginary’ by virtue of the fact that it was expected.” In other words, if it hadn’t been the Titanic sinking, it could easily have been something else. And if Robertson’s novel hadn’t predicted it, it could have been some other novel.

Žižek is suggesting that we would not have been nearly as obsessed with “the Titanic” now or even, arguably, right afterward, had it not been for how uncomfortably closely it happened to match a zeitgeist, the mood of the ending of an era of peaceful progress and stable class distinctions that preceded it. Indeed it was this coincidence—not just with Robertson’s novel but with the whole mood of the times—that actually made it such a trauma, not the other way around, and this is why so much ink has been spilled to interpret and find meaning in it. People incessantly examined the disaster to explain how the “unthinkable” could have happened, and in the process, inevitably turned up a coincidence that looks truly uncanny in in hindsight. Žižek would say the “coincidence” is really a kind of perspective mistake: allowing the retroactive rearranging of symbolic meanings to influence how we perceive the ordinary march of causality.

When we place 9/11 in context, too, some of its coincidences seem less uncanny. The size, stature, and indeed audacity of the towers invited fantasies of audacious conquest, which could readily be expected to be expressed not only in actual real-life terror attacks but also in comic books, disaster movies, and acrobatic stunts. Indeed, terrorists had already attempted to destroy them, which surely planted the seeds of the idea in the collective unconscious as well as in the minds of those who worked in the towers.

But at a certain point—although admittedly that point is fuzzy—the parsimony of the skeptical explanations dwindles relative to the “paranormal” explanation. No amount of evidence for this will sway a hardened skeptic, but abundant evidence for precognition, premonition, and precognitive dreaming exists in parapsychology research. If we are willing to accept any of it as valid, then it means any explanation or account of 9/11 that fails to take into account how such a monumentally traumatic event may have been at least unconsciously foreseen—not by “the government” but by ordinary people, and expressed in their dreams and creative artworks—would actually be inadequate and distorted.

Synchronistic Bias?

The great dream interpreter of the 20th century was of course Freud. His legacy, psychoanalysis, is often thought of as the rule of the present by the past (or as director P.T. Anderson puts it in his Fortean film Magnolia: “We might be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us”). But that’s not completely true in Freud and even less true in some of his followers. The past is always given its meaning in the present, and so the influence of the past always changes. As events inscribe themselves in our ongoing refashioning of memory, we constantly rearrange the past and give it new symbolic shape. Memory readily selects from its infinite storehouse of associations those that match true events, and produce what can look in retrospect like “impossible” coincidences or the inexorable workings of fate. Since we tend to remember events that are significant to us, it produces what might be called a synchronistic bias to our perception.

If we are going to defend a truly synchronistic or paranormal argument for prophetic dreams, visions, and artworks, we need to confront this psychoanalytic argument: that the associative architecture of memory itself is an “acausal connecting principle,” and that what we live as open-ended in the present can in hindsight look deterministic—even uncannily so—when it is not.

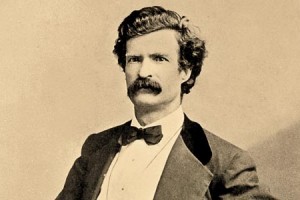

An example of this could be Mark Twain’s precognitive dream about his brother Henry’s death, which Jeffrey Kripal describes in his recent book Comparing Religions

An example of this could be Mark Twain’s precognitive dream about his brother Henry’s death, which Jeffrey Kripal describes in his recent book Comparing Religions. Twain reported that in 1858 he had a dream of his brother lying in a metal casket in a suit of his own clothes and with a bouquet on his chest; a few weeks after this dream, Twain wrote, he received news that Henry had been injured in a boiler explosion aboard the steamboat they were both working on; Henry later died of an overdose of morphine given to kill his pain. In the morgue, Twain beheld the exact scene from his dream, including the clothes and the exact bouquet. It sounds uncanny, but in a series of posts on his very interesting blog, Journal of a UFO Investigator, religion scholar David Halperin does some keen Freudian literary forensics to reexamine the story, putting it back in context and bringing in some very telling clues from Twain’s fictional works about the conflicted feelings the writer held for his more upstanding, “goody-goody” brother.

Halperin deduces from evidence of intense brotherly resentment in Twain’s fiction that he would have had a lifelong unconscious death wish for Henry, and thus would probably have had many dreams, over the years, about him dying. It thus (according to Halperin’s reasoning) might not actually be too strange a coincidence for Twain, upon seeing his brother in a coffin after an unfortunate boiler accident on a Mississippi River steamboat, to recall having dreamed approximately the same thing and formed the notion that he had had a premonitory dream about it. It is significant, Halperin suggests, that Twain never wrote his dream down until 1906, giving his memory ample time—almost half a century—to sort and rearrange events into a more seamless narrative of psychic connection … and brotherly love. Halperin might have added that Twain’s retrospective interpretation at that late date would have fit well with the then-recent theories of psychical research pioneer Frederic W.H. Myers, that trauma is the energy fueling psychic phenomena like telepathy and, perhaps, premonitory dreams.

Psychoanalysis has always provided a halfway house for people who on one hand share Hamlet’s humanistic sense that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in reductive materialistic philosophy but who are nevertheless a bit afraid of the truly supernatural—or what we would now call paranormal—alternative: a universe in which things like ESP and ghosts really exist, and in which the mind can know the future or interact with matter in some mysteriously occult fashion. It’s a halfway house I myself have lived in most of my adult life. Halperin himself admits to precisely this ambivalence in another blog post on Robertson’s novelistic ‘prediction’ of the Titanic disaster: “I don’t want to believe in precognition,” he writes; “The philosophical implications are too daunting.”

But being biased against belief makes us no more clear-headed about the issues involved than wanting to believe. At what point does resolute skepticism force us to accept explanations that are actually more convoluted than what really appears to be going on, however “impossible”—that information, or emotion, is just ‘simply’ traveling backward in time from a monumentally upsetting/traumatic event? Even Twain’s dream, which is easily given a more or less mundane psychoanalytic explanation when taken in isolation, appears far more plausibly premonitory when placed alongside the countless similar examples through the history of dream recording and psychical research—mountains and mountains of cases, all fitting a fairly specific pattern of traumatic events sending shock waves through space and time via some sort of psychic ether.

We Are All Murderers

In his Freudian flight from precognition, Halperin hits on something crucial, I think, about the case of Twain’s dream, which I think applies to the dreams and prophecies of the Titanic and 9/11 too, and which also points to an interesting new way of thinking about the intersection of psychoanalysis and parapsychology and the paranormal dimensions of trauma.

He points out that, far from welcoming the reality of Henry’s accidental death on the Mississippi, Twain would have reacted with guilt. That’s the normal reaction when a person finds that dark wishes they had casually or unconsciously harbored have (impossibly) come true. This is because in our irrational, superstitious unconscious minds, we feel responsible for actually causing the calamities we’ve dimly thought of or wished for.

Žižek could have keyed in on the role played by guilt in the Titanic story too: The trauma of the Titanic was not merely the fact that everyone had been expecting some spectacular disaster to befall the rich and then were shocked when it happened; the trauma was that they had actually been wishing for such a disaster—in exactly the same way Twain may have vaguely or unconsciously wished for his brother’s death. Indeed many who saw the front page of The New York Times on April 15, 1912 must have felt on some very dim unconscious nonrational level that their wishes/desires had actually somehow caused the iceberg to sink the ship—it’s just the way the unconscious mind (which is itself like the huge dangerous submerged portion of an iceberg) works.

Žižek could have keyed in on the role played by guilt in the Titanic story too: The trauma of the Titanic was not merely the fact that everyone had been expecting some spectacular disaster to befall the rich and then were shocked when it happened; the trauma was that they had actually been wishing for such a disaster—in exactly the same way Twain may have vaguely or unconsciously wished for his brother’s death. Indeed many who saw the front page of The New York Times on April 15, 1912 must have felt on some very dim unconscious nonrational level that their wishes/desires had actually somehow caused the iceberg to sink the ship—it’s just the way the unconscious mind (which is itself like the huge dangerous submerged portion of an iceberg) works.

It is a psychoanalytic commonplace that, in our unconscious, we are all murderers. When real events accidentally fulfill our unconscious wishes—serve them up to us on a platter—people react with weird conflicting emotions they can’t fully acknowledge or process. News of the Titanic’s sinking would have produced in people not directly touched by the tragedy an unbearable and even unspeakable mix of contradictory emotions that included shock, horror, and sympathy, but also fascination and excitement, as well as a vague guilt for (unconsciously at least) having harbored murderous class resentments focused on the cosmopolitan elite they read about in The New York Times’ society pages. They would have thus “enjoyed” the news—eagerly read the story and talked about it, feeling a complex mix of weird fascination and excitement and guilt as well as horror.

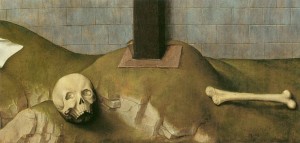

What we particularly fear to see is a “body” that reminds us of our guilty enjoyment. Thus when the Titanic’s remains were finally discovered by Robert Ballard’s undersea cameras in the early 1980s, National Geographic readers gazed on the shadowy photos with a spooked fascination or even a kind of vertigo. Žižek wrote that, “By looking at the [Titanic] wreck we gain an insight into the forbidden domain, into a space that should be left unseen: visible fragments are a kind of coagulated remnant of the liquid flux of jouissance, a kind of petrified forest of enjoyment.”

What we particularly fear to see is a “body” that reminds us of our guilty enjoyment. Thus when the Titanic’s remains were finally discovered by Robert Ballard’s undersea cameras in the early 1980s, National Geographic readers gazed on the shadowy photos with a spooked fascination or even a kind of vertigo. Žižek wrote that, “By looking at the [Titanic] wreck we gain an insight into the forbidden domain, into a space that should be left unseen: visible fragments are a kind of coagulated remnant of the liquid flux of jouissance, a kind of petrified forest of enjoyment.”

9/11 reflects this same phenomenon, of course. For Americans who did not live in Manhattan or work at the Pentagon and who didn’t actually lose loved ones or friends in the attacks, the objective horror of the deaths and destruction and the feeling of national vulnerability were not the sole source of the trauma; the trauma included an added, unspeakable dimension: the contradiction between these aversive facts and our own guilty enjoyment of the cinematic spectacle, our awe at its audacity, and the incredibly warm, positive collective emotions we all shared in days following. This unspeakable enjoyment, not “the thing itself,” explains our collective obsession, re-watching the planes crashing into the towers again and again and again, dwelling endlessly on images of the towers’ wreckage in the poisonous haze, re-living and commemorating that day in our imaginations and our words.

Just as the Titanic fell conveniently into a fantasy space that history had prepared for it, 9/11 fell into a fantasy space that had been prepared for it by decades of disaster cinema and growing social antagonisms. No matter what side of the political fence you were on, it gave everyone mission and meaning—either to go and teach the Muslim world a lesson or to stand up for human rights and intercultural tolerance in a time when our country’s core values seemed in danger of evaporating. 9/11 made us all feel important, and it temporarily gave us back our national pride and unity.

Frederic Myers thought trauma was the energy underlying psychic connections between people, an argument developed by Kripal: “strong emotion (pathos), particularly around trauma and death, is the most common catalyst of robust paranormal events. Trauma, it seems, is what ‘electrifies,’ ‘zaps,’ or ‘magnetizes,’ and hence empowers the imagination. Trauma is the technology of telepathy.” I want to suggest, though, that “trauma” doesn’t quite capture what it was that may have echoed back through time, feeding people’s dreams and premonitions and artworks in the days, months, and decades prior to 9/11/2001 (or prior to April 14, 1912); it was rather the unacceptable mix of horror, guilt, giddy excitement, and awe—the way we derive enjoyment from tragedy, which cannot be consciously acknowledged—that carried that psi signal. Lacanian psychoanalysis calls it jouissance.

No Known Outside the Known

There is no equivalent word in English that captures the pleasurable-painful horror-in-bliss (or blissful horror) of jouissance—it is usually translated simply as enjoyment—but it is one of the core concepts in Lacanian psychoanalysis. Symptoms had been understood by Freud to be a way of “working through” or exorcising the pain of traumatic events or thoughts via repetition, but Lacan reversed this conception: Symptoms are actually the way we reorganize our life in order to continue to derive a secret enjoyment from something that consciously causes us suffering, pain, or revulsion. Symptoms are repetitious, ritualistic acts that attempt to manage this contradiction. The warp of our imaginary-symbolic spacetime produced by this contradiction, and our inability to be rid of our jouissance, something that is always “glued to our heel” (as Lacan put it), is what causes the strange tail-chasing, repetitive “orbiting” behavior of all neurotic symptoms. Could it also account for the spacetime distortions seen in precognitive and premonitory phenomena?

Jouissance, the secret painful enjoyment at the dark heart of our symptoms, is the “only substance acknowledged by psychoanalysis,” according to Žižek. Because it exists beyond symbolism and imagination, this unspeakable enjoyment belongs to the domain that Lacan called the Real—basically, the unknown and unknowable. Its unknowability accounts for the way we have trouble localizing it, either in ourselves (where we don’t quite want it) or in others who are presumed to have stolen it from us (the basic fantasy at the root of racism and sexism). The farther away we imagine “our” lost enjoyment, the bigger it seems to be, almost like the “dolly zoom” special effect used in Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

Jouissance, the secret painful enjoyment at the dark heart of our symptoms, is the “only substance acknowledged by psychoanalysis,” according to Žižek. Because it exists beyond symbolism and imagination, this unspeakable enjoyment belongs to the domain that Lacan called the Real—basically, the unknown and unknowable. Its unknowability accounts for the way we have trouble localizing it, either in ourselves (where we don’t quite want it) or in others who are presumed to have stolen it from us (the basic fantasy at the root of racism and sexism). The farther away we imagine “our” lost enjoyment, the bigger it seems to be, almost like the “dolly zoom” special effect used in Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

The fact that enjoyment belongs to the radically unknown space of the Real contains potentially interesting implications for parapsychology. Because enjoyment exists suspended in a protected or bottled state of unknowability (the symptom that preserves our proximity and distance), it is like the wave function in Quantum physics: It cannot be subjected to measure and differentiation and localization. It is literally “nonlocal” in both time and space. The symptom is thus an atemporal, acausal construct that defies rational analysis because its meaning-cause—its reason for being, as explained in words—lies always somewhere off in the future.

Žižek has described at length in his books how jouissance plays a sort of acausal role in our symptoms; he has always invoked science fiction stories (and Wagner’s Parsifal—see my “Passion of Einstein” post) to illustrate how psychoanalytic symptoms are actually caused by a future event that also cures them, through a kind of “time-loop” logic. Careful to avoid any hint of paranormal thinking or the dreaded “New Age obscurantism,” he is cautious to specify that he is referring to the retroactive reordering of the symbolic universe discussed previously: the way meaning only exists in the present configuration of symbols and signifiers, which are constantly being reshuffled and transformed (in other words, the past that the present affects is simply the known past, the past as it appears in hindsight through the symbolically structured filters or overlay of our perception and memory).

But this strikes me as a defense mechanism of a briliiant materialist whose brilliance has led him—oops—to discover the insufficiency of material causation. Because consider: There is no known outside the known. Once you grant that enjoyment exists outside the known, in the domain of the Real, you cannot then specify that it has any knowable properties—such as only existing here and now and not anyplace else, or traveling in only one temporal direction. (You can’t even exactly say what emotion it corresponds to—it’s sort of all of them, and none.)

So, what if we take literally, rather than figuratively, the idea that enjoyment is radically outside of knowability and locality? Could enjoyment, particularly when it is bottled in a symptom, be a kind of nonlocal medium that not only connects people across space (telepathy) but also connects people to themselves through time?

Remember: As J.W. Dunne noted in his An Experiment With Time, precognitive or premonitory dreams aren’t about future events, they are about one’s own learning of those events. What I’m proposing builds on this assumption: It may not be traumatic events per se that reverberate through the psychic ether, but rather our own ‘jouissant’ reaction to learning of those events. It is this reaction, which we have no way of consciously understanding, that gets turned into premonitory dreams and art.

Eating From the Same Plate

Throughout his books, Žižek likens enjoyment (the one and only substance) to the identical green mush eaten by the separate diners at a chic restaurant in the movie Brazil, each of whom has their own unique picture of what their meal should be standing over identical formless lumps the plates. The idea is that enjoyment is all the same, there’s only one enjoyment, even though we all perceive it differently, within different symbolic and imaginary frames, and thus have a difficult or impossible time recognizing that our enjoyment is actually shared. The diners are all eating the same formless enjoyment … but to make the analogy fully correct, fully true to Žižek’s own argument, the diners should all actually be eating from the same plate—for if it is truly unknowable and unmeasurable, this substance of the Real cannot be divided or differentiated or portioned; their “separate plates” are really mirage reflection of a single plate of enjoyment, “one thing.”

More to the point, if the diners all eat from the same plate, that same plate could be eaten simultaneously by themselves in the past, and future. If we think of jouissance this way, like an ‘out of space and time’ singularity we are all in contact with, it could serve as precisely the “acausal connecting principle” that Jung was looking for in his somewhat muddled concept of synchronicity.

More to the point, if the diners all eat from the same plate, that same plate could be eaten simultaneously by themselves in the past, and future. If we think of jouissance this way, like an ‘out of space and time’ singularity we are all in contact with, it could serve as precisely the “acausal connecting principle” that Jung was looking for in his somewhat muddled concept of synchronicity.

A dream that amazingly comes true, or a premonitory obsession that is verified, or a creative artistic inspiration that is uncannily mirrored in a real future event are all examples of “symptoms” in miniature: Irrational behaviors or thoughts or feelings that find their meaning or “answer” only in some unsettling or traumatic future occurrence. Perhaps it is even precisely our effort to “repress” the unacceptable part of our traumas—that is, to split them and bury the half we don’t want to see (our enjoyment)—that results in acausal, atemporal phenomena like precognitive dreams and premonitions.

Freud wrote of “the return of the repressed,” although it is the concept of repression that has tarnished his reputation most among scientific psychologists: While the unconscious exists, no evidence has ever been found for repression. Supposedly ‘repressed’ memories that are ‘recovered’ in hypnosis or therapy, for instance, are often false or fabulated. Real, verifiable traumas are forgotten and remain inarticulable, hard to put into words because we lacked the necessary concepts at the time they happened, but they are not actively buried by any censoring force in the psyche. A trauma victim usually awakens to the trauma spontaneously at some point, not with the ‘aid’ of discredited methods like hypnosis. But what about the unbearable contradictory feelings that might accompany a trauma? What about the unbearable dimension of enjoyment?

Perhaps repression does exist in some sense, and we have been looking for it in the wrong place. What if our symptoms are able to sequester certain thoughts or feelings, for instance guilty feelings about enjoying something objectively horrible, in a place they really can’t be found—the past? Perhaps it is precisely our repressed jouissance that “returns” in our own past, where we can have no way of understanding its meaning. If something like that is the case, then our present symptoms may contain the “repressed” of our future.

Synchro-causality

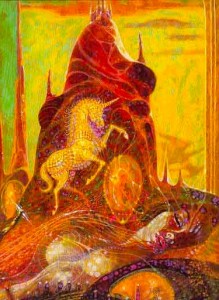

To illustrate on a small scale how temporally displaced repressed jouissance might exert a causal influence on the past via a symptom, let’s consider another uncanny case of “death on the Mississippi.” On his always interesting blog The Secret Sun, Christopher Knowles devoted a series of posts to the synchronistic perfect storm that surrounded the life, loves, and career of Scottish singer Elizabeth Fraser (right), the lead singer of Cocteau Twins (and also one of my favorite musical artists). In the mid-1990s, Fraser entered into an obsessive, intense romance with the singer Jeff Buckley (below), who had just published a wildly critically acclaimed debut album (Grace) revealing an astonishing talent that mirrored that of his father Tim Buckley. The elder Buckley had died young of a drug overdose in 1975 without really ever getting to know his son, and it was hearing Fraser’s haunting cover of his father’s 1970 “Song to the Siren” in 1994 that, according to Knowles, drove Buckley to seek out Fraser, at which point they became intensely involved for a couple of years.

To illustrate on a small scale how temporally displaced repressed jouissance might exert a causal influence on the past via a symptom, let’s consider another uncanny case of “death on the Mississippi.” On his always interesting blog The Secret Sun, Christopher Knowles devoted a series of posts to the synchronistic perfect storm that surrounded the life, loves, and career of Scottish singer Elizabeth Fraser (right), the lead singer of Cocteau Twins (and also one of my favorite musical artists). In the mid-1990s, Fraser entered into an obsessive, intense romance with the singer Jeff Buckley (below), who had just published a wildly critically acclaimed debut album (Grace) revealing an astonishing talent that mirrored that of his father Tim Buckley. The elder Buckley had died young of a drug overdose in 1975 without really ever getting to know his son, and it was hearing Fraser’s haunting cover of his father’s 1970 “Song to the Siren” in 1994 that, according to Knowles, drove Buckley to seek out Fraser, at which point they became intensely involved for a couple of years.

Their intense/obsessive relationship was on-again/off-again, and eventually Buckley left Fraser, becoming involved with another woman. It was around this time that he sequestered himself in a rented house in Memphis to write songs for his second album. Just as his musicians were on their way to Memphis to begin recording—literally, while they were in the air—Buckley took an impromptu swim in a tributary of the Mississippi and got caught in the undertow generated by a passing boat. His body was found a couple days later.

Their intense/obsessive relationship was on-again/off-again, and eventually Buckley left Fraser, becoming involved with another woman. It was around this time that he sequestered himself in a rented house in Memphis to write songs for his second album. Just as his musicians were on their way to Memphis to begin recording—literally, while they were in the air—Buckley took an impromptu swim in a tributary of the Mississippi and got caught in the undertow generated by a passing boat. His body was found a couple days later.

The coincidences and premonitions are too numerous to summarize (you should just read Knowles’ posts), but at their core are the fact that Fraser’s entire career seems in hindsight like a protracted achingly beautiful omen of Buckley’s death. She wrote and sang again and again about water, drowning, and sirens luring people to a watery grave (“Lorelei,” “Sea, Swallow Me,” etc.). Indeed her cover of Jeff’s father’s “Song to the Siren” (about being drawn to a siren who rejects her, and whom she then pleads to come be enfolded in her watery arms), for the supergroup This Mortal Coil’s album It’ll End in Tears, is one of her best-known performances. That was indeed a “siren song” in the sense that it summoned Jeff Buckley to her, and in hindsight was just one of many songs (you should also look at Cocteau Twins’ videos and album covers) whose imagery of water and loss seemed to foretell to the disaster to come. Fraser received news of Buckley’s death when in a studio in England recording the song “Teardrop” with the band Massive Attack for their album Mezzanine—another high point in her brilliant career, which largely faded after that point.

Again, there’s no way to measure coincidence. Is this all just a reshuffling and reordering of events in hindsight to construct a “destined” meaning to Jeff Buckley’s death? We can never disprove that, but Knowles does a good job of persuading that something more had to be going on. But if so, what? The standard archetypal, “synchromystic” explanation would be that somehow the “siren” archetype imprinted itself on history via these hapless individuals, who, as Knowles suggests, “were merely acting out roles written for them long before their grandparents were born.”

A skeptic willing to minimally accept that Buckley’s drowning was more than coincidence but that there was nothing paranormal occurring could go the halfway-house psychoanalytic route, offering that Fraser’s siren obsession infected Buckley’s unconscious mind and gave specific form (drowning) to an unconscious death wish, perhaps somehow to follow his father to an early grave. Less boldly, you could also suggest her obsession with water spilled over (so to speak) onto Buckley and simply increased his statistical likelihood (a) of taking spontaneous swims and (b) of perishing in the water. Žižek, for whom the past is constantly being reshuffled and given new meaning within the present Symbolic order, would probably say Buckley’s drowning was like a final psychoanalytic interpretation that “answered” Fraser’s symptom (i.e., her career) and effectively cured her of it. Indeed, as Knowles notes, Fraser has seemed to have lost her otherworldly muse and become, perhaps for better as well as worse, just a normal human being in its aftermath. In all these variants, the apparent synchronicity only appears as such in hindsight.

But if we grant that intense/traumatic enjoyment may operate nonlocally in a person’s life, I would propose that the most parsimonious and even realistic explanation of the coincidences surrounding Fraser and Buckley would be one that takes Žižek’s cautious symptom retrocausality and literalizes it: The death of Fraser’s eventual lover and muse, Jeff Buckley, was a trauma that reverberated backward in time along the resonating string of her creative enjoyment, becoming an inchoate idee fixe that appeared again and again and again in her music. Fraser channeled or drew from this trauma as the source and inspiration for most of her career, without having any way to recognize that it was a terrible future shock that she was feeling, seeing, or channeling.

Enjoyment as a Carrier

“Ready to sing, my sixth sense peacefully placed on my breath,

and listening, my ears know that my eyes are closed”

—Elizabeth Fraser/Massive Attack, “Group Four”

According to Knowles, Fraser claimed in the early 1990s that she had been the victim of sexual abuse as a child. This is possibly significant. Creative people are often “driven” (perhaps not the right word) by a trauma in their past, and I believe it is something of a commonplace in studies of paranormal phenomena that some early trauma (like abuse, or a death of a parent or sibling, or a difficult birth) is often found in people receptive to otherworldly or paranormal events. Also, given what we know about the psychotherapeutic zeitgeist of the 1990s and the tendency to overinterpret or embellish (and in many cases invent, though I’m not suggesting that here) abuse trauma memories, she may even have misrecognized or overemphasized the pain driving her as her past abuse trauma when the trauma was “really” something ahead in the future she had no way of knowing about or believing in. Could her outrageous creative talent have been like a short circuit between the twin traumas bookending her career?

In other words, I am not trying to explain Buckley’s death here: That was, I am proposing (for the sake of argument), “just” an accident. I am trying to explain the retroactive effect his death might have had on a woman’s creativity (and heck, maybe even his own father’s creativity all the way back in 1970 when he wrote “Song to the Siren”). Buckley’s death’s appearance of meaningfulness was the illusory result of his lover’s whole lifetime oeuvre leading up to it; but (and here’s where it becomes ‘paranormal’) that body of work was indeed motivated by, inspired by, that future death and the complex unbearable feelings it would provoke in her, which reverberated into the past, along the atemporal resonating string of her creative jouissance (her “sixth sense … placed on her breath,” as she describes it in the song “Group Four”). (On his blog, Bruce Duensing speculates that fear is a “carrier wave” for paranormal phenomena; I think carrier wave is a great metaphor, so long as we replace “fear” with jouissance.)

Here’s the thing, though: The shock of Buckley’s death would have been not only the trauma of his loss (she had already lost him effectively, as he had broken up with her), but the way his drowning revealed the “true meaning” of all her songs, the way it perfectly fit or matched the space her own art had repeatedly created for it, effectively confirming, at least on an unconscious level, that she was indeed the otherworldly powerful medium and “siren” that she had always allowed herself to be perceived as. How could her unconscious mind not have felt a terrible glee and awe (as well as guilt) for precisely what Knowles even intimates her siren powers actually might have done, which was channel or focus obscure dark magical forces that perhaps drew Buckley to his doom?

Here’s the thing, though: The shock of Buckley’s death would have been not only the trauma of his loss (she had already lost him effectively, as he had broken up with her), but the way his drowning revealed the “true meaning” of all her songs, the way it perfectly fit or matched the space her own art had repeatedly created for it, effectively confirming, at least on an unconscious level, that she was indeed the otherworldly powerful medium and “siren” that she had always allowed herself to be perceived as. How could her unconscious mind not have felt a terrible glee and awe (as well as guilt) for precisely what Knowles even intimates her siren powers actually might have done, which was channel or focus obscure dark magical forces that perhaps drew Buckley to his doom?

I’m doubtful Fraser’s witch powers actually reached out across the ocean and drew Buckley into the Mississippi, but Fraser’s unconscious mind might have believed precisely that possibility, and this would have added to the trauma, making his death “speak louder” into the past, back along that resonating string (or carrier wave) of her creativity. Her guilty enjoyment would have been her unconscious belief in the power of her own siren song. Her symptom—her music—through its repetition of themes of sirens and drowning, could have boosted the ‘gain’ of the painful guilty enjoyment-signal she was receiving from the future, amplifying the obviousness of the coincidence (and thus the traumatic shock) when she learned that Buckley died and the way he had died.

This is all (wild) speculation, obviously. But I do think the dark complexity of our reactions to traumas, ranging from minor emotional disturbances to personal tragedies to terrorist attacks, could be the key not only to premonitory dreams and like phenomena but also to understanding many apparent synchronicities. Some synchronicities could really be misrecognized precognition of our own guilty enjoyment.

The Solaris Mind: Hypnagogia, Meditation, and Insight

A classic motif in science fiction is that humanity ventures to the farthest reaches of space only to find, impossibly, something of our own that we had forgotten. Stanislaw Lem’s 1961 novel Solaris, about a planet covered by a viscous ocean that manufactures simulacra from its observers’ unconscious, is probably the purest expression of this idea.

The backstory of Lem’s novel is that the planet Solaris captured the interest of its discoverers because of its impossible stable orbit around its double star. Exploration revealed that its ocean somehow, perhaps sentiently, shifted the planet’s center of mass to steer it in its orbit. But even more mysteriously, it generated beautiful sculptural forms, rising high into the atmosphere and then dissolving back into it a few hours or days later. This ocean seemed dimly and inscrutably intelligent, so a station was placed in orbit to observe and study it. After several decades of study, spawning a whole library of inconclusive research and scientific controversy, some of the forms generated by the ocean started to resemble human tools and objects, as though pulled from the memories of the scientists observing it. One scientist reports seeing a giant baby rise above the waves out of the fog, but most of his colleagues think he is crazy.

When the protagonist Kris Kelvin arrives on the station to investigate a suspected breakdown among its small crew, he finds that synthetic people from the scientists’ pasts have started to appear on the station, confronting them with their own darkest desires and painful regrets, driving them to the brink of madness—and one even to suicide. Soon after his arrival, a perfect simulacrum of his ex-wife Rhea, who had committed suicide after he cruelly abandoned her years earlier, appears in his quarters, without any memory of how she got there.

Solaris has been adapted twice for the screen—by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1972 and by Steven Soderberg in 2002. Both adaptations concentrate on the ambivalent romance that develops between Kelvin and his resurrected ex, largely ignoring the planet itself and its mimetic ocean-forms. This is unfortunate (and it disappointed Lem too), because Solaris the planet is one of the most fascinating and awe-inspiring creations in science fiction.

Solaris has been adapted twice for the screen—by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1972 and by Steven Soderberg in 2002. Both adaptations concentrate on the ambivalent romance that develops between Kelvin and his resurrected ex, largely ignoring the planet itself and its mimetic ocean-forms. This is unfortunate (and it disappointed Lem too), because Solaris the planet is one of the most fascinating and awe-inspiring creations in science fiction.

Lem, who died in 2009, remains unsurpassed in his imagining of the possibilities of alien intelligence and human incapability to interpret or understand it. With Solaris, I have no doubt the Polish writer was inspired by the most alien form of our own human intelligence: hypnagogia, the baffling and surreal imagery generated by the unconscious that can be seen clearly on the edge of sleep and in meditative states.

Digesting the Now

Hypnagogic imagery have no doubt inspired art and religion since the dawn of humanity. It was an early scientific observer of hypnagogic phenomena, the psychoanalyst Herbert Silberer, who first noted that these images are often or perhaps always “autosymbolic”—they represent, usually in an astonishingly clever way, some immediate thought or some preoccupation right now, right at the instant they are created. Like dreams, this correspondence to real experience is not immediately obvious but reveals itself readily in free-associative interpretation. I’ve argued elsewhere that dreaming is the punny, playful-associative “art of memory” operative during sleep; hypnagogia is a waking window onto this same process.

Meditators and yogis have always compared the mind to an ocean, in which thoughts are like waves that trouble the surface. I think the playful, ingenious, autistically inscrutable Solaris ocean is an even better, more nuanced metaphor than any dumb old Earth ocean. The mind is a constant mimetic sea, perpetually generating imaginary representations of everything we encounter and think about and experience; it combines and shapes these ghosts effortlessly into brilliant symbolic tableaux and scenes that brilliantly distill the meaning of “gist” of our experience. Hypnagogia shows us this automatic process, the Solaris mind’s constant metabolism of experience.

Meditators and yogis have always compared the mind to an ocean, in which thoughts are like waves that trouble the surface. I think the playful, ingenious, autistically inscrutable Solaris ocean is an even better, more nuanced metaphor than any dumb old Earth ocean. The mind is a constant mimetic sea, perpetually generating imaginary representations of everything we encounter and think about and experience; it combines and shapes these ghosts effortlessly into brilliant symbolic tableaux and scenes that brilliantly distill the meaning of “gist” of our experience. Hypnagogia shows us this automatic process, the Solaris mind’s constant metabolism of experience.

We ordinarily don’t discern or detect this continual churning out of image-representations because it is so subtle, so in the background. It is only when the foreground stuff of conscious mental chatter and active thinking is quelled or silenced that it becomes apparent. Meditators interested in the phenomenon can learn to stabilize the edge state on the verge of sleep where these forms can be witnessed and recorded. Hypnagogia can be used to access lucid dreams (the “wake-induced lucid dream” or WILD method described by Stephen LaBerge); and many consider the hypnagogic mind to be uniquely receptive to psychic phenomena. (The most comprehensive book on the topic is the wonderful Hypnagogia, by Andreas Mavromatis—highly recommended.)

But the fact that we mainly detect our preconscious image-building on the edge of sleep should not lead us to believe that it only happens then. This function, an aspect of what Sartre and Lacan both called “the Imaginary,” is a constant process, one that is essential to thinking and the associative bundling of experience so that it can feed our memory mill.

Symbolically metabolizing experience by reducing it to cartoon-dioramas firstly creates mental objects that can be fastened with symbolic labels and manipulated in thought, like toys and action figures we move around in our mental sandbox. They are a basic requirement for thinking. And because they are minimally detailed, these cartoon replicas probably maximize the amount of experience that can be fit into the limited workspace of our working memory: We can only keep 4 or 5 discrete “items” in our heads at one time.

The dioramas of the Imaginary thus facilitate the present situation forming a “chord” with immediate past and future experiences, giving thickness and substantiality to the Now. And by reducing experience to something sketch-like, they likely enable more of that experience to get through the working-memory bottleneck to be stored and transferred to long-term memory later on. The reduced, cartoon-like symbolic representation that can be unpacked at the other end, so to speak, through webs of associative linkages, just like dreams (which, I argue, are long-term memories in the process of formation—see below).

“Every thing fits into its own shape”

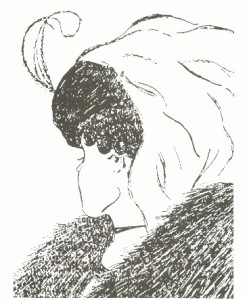

The Solaris mind’s incessant brilliant mimesis, as crucial as it is for functioning in the world and enabling us to remember our experiences later, is also to blame for the foremost obstructions of spiritual vision: the arising of the idea of self, and with it the constant fading of presence (that is, “being here now”) that has been the bane of meditators and mystics for millennia.

To free us from having to give all our attention to the present moment, the imagination constantly replaces our naked awareness of the world with sketch-like scenes of “I seeing.” You can experience this yourself: Just take a deep breath, exhale, and focus visually on an object in front of you. Initially there is a silent vivid sense of full presence with the object—the object richly and brightly fills your attention—but after just a few seconds the vividness of the object fades slightly as a faint, subtle mental diorama of “me seeing this” emerges in your awareness to compete with it; you might also notice further layers of imagination, like a background meta-awareness of “being seen seeing” (the constant inner haunting presence that Lacan called “the Gaze”). Naked awareness is thus perpetually obscured in consciousness with new virtual ghost-representations—literally, every few seconds, new puppet-subjects and new gazes form, in a slow but incessant pageant of simulacra that represent the self.

To free us from having to give all our attention to the present moment, the imagination constantly replaces our naked awareness of the world with sketch-like scenes of “I seeing.” You can experience this yourself: Just take a deep breath, exhale, and focus visually on an object in front of you. Initially there is a silent vivid sense of full presence with the object—the object richly and brightly fills your attention—but after just a few seconds the vividness of the object fades slightly as a faint, subtle mental diorama of “me seeing this” emerges in your awareness to compete with it; you might also notice further layers of imagination, like a background meta-awareness of “being seen seeing” (the constant inner haunting presence that Lacan called “the Gaze”). Naked awareness is thus perpetually obscured in consciousness with new virtual ghost-representations—literally, every few seconds, new puppet-subjects and new gazes form, in a slow but incessant pageant of simulacra that represent the self.

By “self” I don’t just mean the ego or “I” in the diorama. Every object of perception too, by being copied in the imagination, assumes a virtual ghost presence or double. Whenever our eyes fall on an object, this interplay of the ghost-making Solaris mind and the webs of linguistic symbols we map onto those image-representations produce the sense of recognition, a sense of “what it is,” enabling a labeled image-object to be manipulated in thought. This “what it is,” or itself-ness, the fiction of self-identity, is—when we become attached to it or believe in it—the ultimate stumbling block toward spiritual liberation. Belief in the self is the basic error and even absurdity that, for Buddhists, is the fundamental reason for human suffering.

The reason an object’s self-identity is absurd was explained best, I think, by Ludwig Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations:

“A thing is identical with itself.”—There is no finer example of a useless proposition, which yet is connected with a certain play of the imagination. It is as if in imagination we put a thing into its own shape and saw that it fitted. (We might also say: “Every thing fits into itself.” Or again: “Every thing fits into its own shape.” At the same time we look at a thing and imagine that there was a blank left for it, and that now it fits into it exactly.) Does this spot O “fit” into its white surrounding?—But that is just how it would look if there had been a hole in its place and it then fitted into the hole…

So, in short, the Solaris mind takes the alive Heraclitean flux of experience and constantly copies and fossilizes it in cold dead representational dioramas suitable to be thought about and metabolized in memory. The battle of meditative engagement is with this continuous force of autosymbolic imagining (not just the more obvious verbal chatter). The aim is not to obliterate our mental models of ego and self—we need these illusions to function in the world—but to shift the balance: from living completely in the empty, frustrating world of mental representations (images and words) toward abiding for greater stretches of time in the wordless, imageless, blissful Real that lies beyond and outside them.

The Solaris Mind Produces Teachers

During the day, because its imagery is so yoked to the senses, the Solaris mind generates innocuously realistic images that are hard to detect, because they so closely resemble the “shape” of our lived experience and then are immediately washed away by the thoughts that are seeded from them—like ocean waves erasing a picture drawn in the sand. When liberated from thought and sense, however, as on the edge of sleep or in meditation, these images assume their more wildly imaginative genius.

The paradoxical effect of withdrawing from the senses and temporarily quelling the flow of verbal and imaginal thought is that it enables daytime hypnagogic images to assume the vivid otherness of full-on waking dreams. These brief visions, flickering out as quickly as they appear, provide “object lessons” that can enlighten and inspire. Famously, artists like Dali have used them for inspiration. August Kekule’s famous “dream” of a snake biting its tail, which gave him the idea of the benzene ring, was actually a waking reverie, a hypnagogic image. When David Lynch