The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

To the Unified Field (via Twin Peaks): David Lynch’s Paintings

“We live in a world of opposites, of extreme evil and violence opposed to goodness and peace. It’s that way here for a reason but we have a hard time grasping what the reason is. In struggling to understand the reason, we learn about balance and there’s a mysterious door right at that balance point. We can go through that door anytime we get it together.” —David Lynch

Many fans of David Lynch’s films are probably aware that he started as a painter and has continued to work in that medium all his life. (For example, they may have glimpsed him at work in his atelier in the documentary that accompanies the Inland Empire DVD.) But it has been frustrating trying to find examples of his paintings and drawings because there has been no single book comprehensively showcasing them. Finally, David Lynch: The Unified Field, the catalogue of an exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he studied as a young man, beautifully displays this “other” side of Lynch’s creativity.

It’s a gorgeous book, with an excellent long essay by Robert Cozzolino. It will do much to help Lynch claim the recognition he deserves as a very serious and original artist in a completely different medium from his film and TV work. I’ve spent days thumbing through it already and it is still full of delights and surprises.

It’s a gorgeous book, with an excellent long essay by Robert Cozzolino. It will do much to help Lynch claim the recognition he deserves as a very serious and original artist in a completely different medium from his film and TV work. I’ve spent days thumbing through it already and it is still full of delights and surprises.

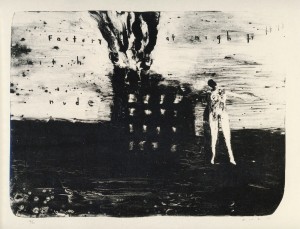

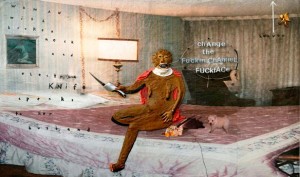

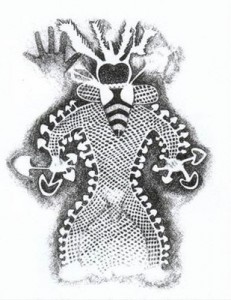

Lynch’s paintings, which are bold, childlike and threatening, remind me of Francis Bacon crossed with a dark Cy Twombly, often integrating thickly spackled paint (he mentions feeling the urge to chew on his paintings) with text that is either ultra-banal or psychotic. They reflect many of the same themes that recur in his movies, such as the violence, madness, perverse sexuality, and even paranormal phenomena that can be found when you peel back the surface of outwardly bland American life—or, that become visible at a smaller scale, when you zoom in. But—and this is crucial—they are also often funny; there is typically a sly poke in the ribs underneath the overt threat. (This is what sets him far apart from Bacon, say.)

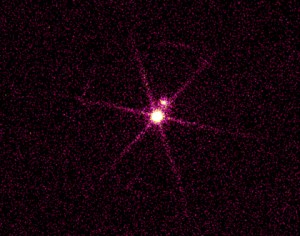

Lynch’s early “moving picture” installation, “Six Men Getting Sick” (which has been recreated for the PAFA exhibition), is like a prototype for many of his later works both in film and on canvas. Six faces imprisoned in a gray-white wall vomit repeatedly; they cannot leave the wall, cannot get up and go to the doctor or even to the toilet, but are trapped in a perpetual materialist hell, purging throughout eternity. It somewhat reminds me of HR Giger’s transhumanist visions of immobilized sentiences trapped and suffering in and from brute matter, although Lynch’s outwardly “ugly” spectacle is far more ambiguous and strange than Giger’s sleek, seductive machine-erotic futurescapes.

Lynch’s early “moving picture” installation, “Six Men Getting Sick” (which has been recreated for the PAFA exhibition), is like a prototype for many of his later works both in film and on canvas. Six faces imprisoned in a gray-white wall vomit repeatedly; they cannot leave the wall, cannot get up and go to the doctor or even to the toilet, but are trapped in a perpetual materialist hell, purging throughout eternity. It somewhat reminds me of HR Giger’s transhumanist visions of immobilized sentiences trapped and suffering in and from brute matter, although Lynch’s outwardly “ugly” spectacle is far more ambiguous and strange than Giger’s sleek, seductive machine-erotic futurescapes.

On one level, Lynch could be called a painter of matter—of vomit, dirt, muck, rust, and biological decay that step in to co-create the world after humans have contributed their part. He is quoted in the opening essay about being allowed to spend time with corpses in the Philadelphia morgue when he was in art school, and the beauty he finds in “organic processes” that he got from his time spent with his father, who was a specialist in tree diseases working for the Forest Service when he was a child in Montana. Throughout his works, abandoned factories, mud and sores, or the brown stains on the made world, all become sublime.

But the matter, even when or especially when it is decaying and messy, is only barely covering over something deeper (or higher). In interviews (and in his brief 2007 book Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity

But the matter, even when or especially when it is decaying and messy, is only barely covering over something deeper (or higher). In interviews (and in his brief 2007 book Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity), Lynch always takes the opportunity to tell people how his own youthful anger and neurosis were cured through Transcendental Meditation and that his creativity is fueled by his twice-daily practice of dipping into the fundamental wellspring he calls the “unified field.” He would thus surely not mind us using his paintings for meditation or as advertisements for the rewards of meditation. Specific altered states of perception I have experienced as a byproduct of my own Zen-influence practice help me pin down exactly what the mysterious X quality in his paintings is—the precise tension they invoke (at least in me).

Buddhist writers don’t like to dwell on the mild altered states produced by meditation, preferring that we not get attached to them, but when you detach from your environment even for very brief periods, the world can afterwards take on a funny, mysterious, alive-yet-dead quality that is full of exciting unseen potential. I have noticed for years that after meditating, the world has an altered character that feels distinctly “Lynchian”: Specifically, it feels like the world has suddenly become the world of Twin Peaks—the ordinary, mundane world, but with something added that is a mix of mysterious, humorous, ominous, and subtly exciting. This is why I was so excited to finally get a book of Lynch’s paintings—to see if they had this same quality. I was not disappointed.

One way to think of the subtly altered state of perception I’m referring to is in terms of the “imaginal” that was described by Sufi scholar Henri Corbin: a kind of transfigured surreality overlaid on or coexisting with the everyday world, shimmering in and out of existence. Objects shine funny, oddly, significantly. They wink, ever so slightly. The importance of everything, even just this ashtray or coffee table or lamp, is ever so slightly elevated because through some subtle alteration of frequency, some slight turn of the dial, the shitty bathroom or grocery store or parking lot you happen to be standing in has suddenly become the VIP section of an international spirit-world airport, where one just might encounter other enlightened beings passing through. Even pieces of garbage or dead leaves are “slightly enlightened” celebrities, and you belong in their exciting world.

I think of this imaginal as a dangerous-feeling and uncomfortable perimeter or no-man’s land that surrounds the blissful Void or Absolute (or “unified field”) that all forms of meditation and mysticism aim for. The ultimate aim is not to linger in this perimeter zone, but you do need to pass through it—and the passage can be really enjoyable and interesting in its own right. This book of paintings confirms for me that Lynch, through his meditation practice, knows about this imaginal no-man’s land and that this is specifically what he is trying to show to us (because the unified field itself can’t be shown). Anything can happen, is about to happen, in this zone, and it pays to be fully awake and alert to the enhanced potential even in the most inanimate of objects and phenomena in it.

I think of this imaginal as a dangerous-feeling and uncomfortable perimeter or no-man’s land that surrounds the blissful Void or Absolute (or “unified field”) that all forms of meditation and mysticism aim for. The ultimate aim is not to linger in this perimeter zone, but you do need to pass through it—and the passage can be really enjoyable and interesting in its own right. This book of paintings confirms for me that Lynch, through his meditation practice, knows about this imaginal no-man’s land and that this is specifically what he is trying to show to us (because the unified field itself can’t be shown). Anything can happen, is about to happen, in this zone, and it pays to be fully awake and alert to the enhanced potential even in the most inanimate of objects and phenomena in it.

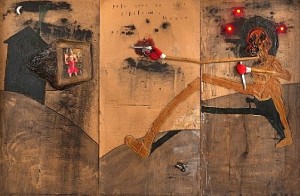

This imaginal is also a feeling of the world being like a veil. I don’t think it is accidental that Lynch’s film and TV work often includes drapery, most famously the “Black Lodge” of Twin Peaks, where strange shapes float behind red velvet curtains. However, what I actually think of more than drapes per se is the billowing dirty plastic covering the bare two-by-fours in the unfinished home where Shelly Johnson spoons baby food into the dribbling mouth of her ominously comatose husband Leo. If there’s any image from Lynch’s “moving picture” world that gives you a sense of what you’re in for with his paintings (such as the ominous triptych “Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House,” above), that would have to be it.

This imaginal is also a feeling of the world being like a veil. I don’t think it is accidental that Lynch’s film and TV work often includes drapery, most famously the “Black Lodge” of Twin Peaks, where strange shapes float behind red velvet curtains. However, what I actually think of more than drapes per se is the billowing dirty plastic covering the bare two-by-fours in the unfinished home where Shelly Johnson spoons baby food into the dribbling mouth of her ominously comatose husband Leo. If there’s any image from Lynch’s “moving picture” world that gives you a sense of what you’re in for with his paintings (such as the ominous triptych “Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House,” above), that would have to be it.

The apparent danger and craziness is not as real as it first appears; it has more to do with our own attitude. Even or especially in his most violent, threatening images, such as “Change the Fuckin Channel Fuckface” (below), or “I Burn Pinecone and Throw in Your House,” you can see Lynch standing back, with a slight mischievous twinkle in his eye, smiling, and you can see that he is actually smiling with you. He wants you to be pulled in, tripped up, as well as held at a slight distance, because this tension has something to teach us, and he wants to help us see it. He is inviting us to ride along with him in his buggy, on an interior journey that he sincerely believes can help everybody.

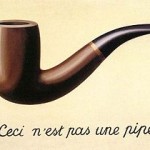

Getting past this imaginal, to the unified field, is not an intellectual exercise of decoding or interpreting hidden meanings: “It’s better not to know so much about what things mean or how they might be interpreted,” Lynch says. “Psychology destroys the mystery, this kind of magic quality. It can be reduced to certain neuroses or certain things, and since it is now named and defined, it’s lost its potential for a vast, infinite experience.” (Half a century ago, Rene Magritte said almost exactly the same thing, reacting against Freudians finding phallic symbols and such in his paintings: “Art, as I conceive it, is resistant to psychoanalysis. It evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist. … Nobody in his right mind believes that psychoanalysis could elucidate the mystery of the universe.”) Yet Lynch’s works bait such interpretation. This baiting and snatching away is part of the point, part of their “M.O.”—which is actually a very Rinzai Zen approach to enlightenment. As I’ve written previously about Mulholland Drive, you must go through the natural impulse to interpret Lynch’s work in order to finally break through the other side, into the irrational and transcendent.

Getting past this imaginal, to the unified field, is not an intellectual exercise of decoding or interpreting hidden meanings: “It’s better not to know so much about what things mean or how they might be interpreted,” Lynch says. “Psychology destroys the mystery, this kind of magic quality. It can be reduced to certain neuroses or certain things, and since it is now named and defined, it’s lost its potential for a vast, infinite experience.” (Half a century ago, Rene Magritte said almost exactly the same thing, reacting against Freudians finding phallic symbols and such in his paintings: “Art, as I conceive it, is resistant to psychoanalysis. It evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist. … Nobody in his right mind believes that psychoanalysis could elucidate the mystery of the universe.”) Yet Lynch’s works bait such interpretation. This baiting and snatching away is part of the point, part of their “M.O.”—which is actually a very Rinzai Zen approach to enlightenment. As I’ve written previously about Mulholland Drive, you must go through the natural impulse to interpret Lynch’s work in order to finally break through the other side, into the irrational and transcendent.

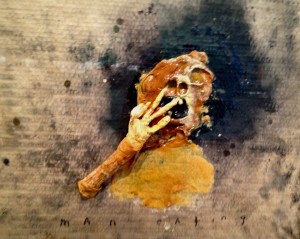

There’s nothing “preachy” about Lynch’s paintings, any more than there is in his movies, but the spiritual message is definitely there if you look for it. One of my favorite pieces in the book is “Holding onto the Relative (with One Eye on Heaven)” (at the top of this post) showing one of his typical disturbing/monstrous brown figures with elongated arms clinging desperately to the pulsating red heart of matter while looking toward the sun and screaming. Lynch’s philosophy I think is made pretty plain here: The frightening dimension is not simply the way things are, but the way we make them because we are afraid of letting go, or are holding on too tightly. Stretched-out arms and “reaching” (as well as arms/hands that are diseased) recur again and again in Lynch’s images, and I think it relates to this idea, and to the opposing forces that we cling to and that threaten to pull us apart.

Ambassadors from Flatland: UFOs and Anamorphosis

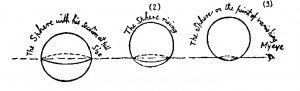

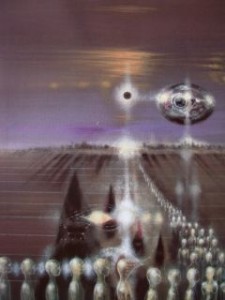

It is frequently suggested that UFOs originate in or at least travel through other, higher dimensions. The examples of interdimensional interaction in E.A. Abbott’s classic fable Flatland are often cited to illustrate how such an intrusion into lower dimensions from higher ones might appear. A sphere passing through Flatland (a world with two spatial dimensions and one of time) would appear to the locals as a point that expanded into a widening circle and then dwindled to a point again and vanished (below). Flatlanders (who are all simple shapes like polygons) would be rather astonished at this violation of their common-sense laws: Things don’t just expand from nothing and then dwindle and disappear again.

Extrapolating to our 4-D reality (3 spatial dimension and 1 time dimension), this does seem like what many UFOs do: They appear out of nowhere, sometimes expanding and changing shape before disappearing again, as though some higher-dimensional object were transiting our dimensionally challenged world. In this view, the UFO we see at any given moment is just the “section” of a 4- or more dimensional spatial object (e.g., a hypersaucer).

Extrapolating to our 4-D reality (3 spatial dimension and 1 time dimension), this does seem like what many UFOs do: They appear out of nowhere, sometimes expanding and changing shape before disappearing again, as though some higher-dimensional object were transiting our dimensionally challenged world. In this view, the UFO we see at any given moment is just the “section” of a 4- or more dimensional spatial object (e.g., a hypersaucer).

But there is another possibility.

The number of dimensions possible in the universe is hotly debated in physics. I’ve seen the number 11 thrown around a lot, for example, although as I understand it most of these dimensions are thought to be somehow “folded into” the four we directly experience. I honestly don’t know what that means, let alone how to envision it. But another even more interesting theory holds that our purely common sense perception of space and time actually overestimates the spatial dimensionality of our world—that there are actually just two dimensions of space, and that the third dimension (volume) is an illusion.

The number of dimensions possible in the universe is hotly debated in physics. I’ve seen the number 11 thrown around a lot, for example, although as I understand it most of these dimensions are thought to be somehow “folded into” the four we directly experience. I honestly don’t know what that means, let alone how to envision it. But another even more interesting theory holds that our purely common sense perception of space and time actually overestimates the spatial dimensionality of our world—that there are actually just two dimensions of space, and that the third dimension (volume) is an illusion.

This is the holographic theory proposed by Dutch physicist Gerard ’t Hooft as an outgrowth of string theory, to explain quantum gravity. Wikipedia describes it this way: “the theory suggests that the entire universe can be seen as a two-dimensional information structure ‘painted’ on the cosmological horizon, such that the three dimensions we observe are an effective description only at macroscopic scales and at low energies.”

Quantum physics is mostly beyond me, I admit, but I do understand general relativity, and doesn’t Einstein’s work already suggests this possibility? As an object approaches the speed of light (gaining mass and energy), it is flattened in the direction of travel, becoming two dimensional; it thus makes some sense that in the “light world” of high-energy particles, two-dimensional space would have to be the norm.

And thus, instead of some kind of enhanced depth, as movie special effects like to portray it, hyperspace would actually be a flat, picture-like place.

From Flatland to Fatland and Back Again

I realize that “painted” is being used somewhat metaphorically in Wiki’s summary, but artistic illusions of spatial depth on flat surfaces (which was partly the subject of my PhD dissertation several years ago) suggest other possible interpretations for how UFOs may actually be interacting with our world—not from higher dimensions but from lower ones.

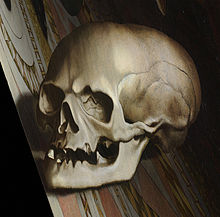

Hans Holbein’s 1533 painting The Ambassadors (at the top of this post) shows a typical Renaissance scene of two important men surrounded by sumptuous worldly goods, but jutting across the bottom of the painting is a strange elongated object (left). From straight on, it doesn’t really look like anything—it has been compared to a baguette—and a viewer might even overlook or ignore the anomaly, regarding it as a mistake or a stain of some kind. It is actually an example of anamorphosis—an image only visible from a very oblique angle.

Hans Holbein’s 1533 painting The Ambassadors (at the top of this post) shows a typical Renaissance scene of two important men surrounded by sumptuous worldly goods, but jutting across the bottom of the painting is a strange elongated object (left). From straight on, it doesn’t really look like anything—it has been compared to a baguette—and a viewer might even overlook or ignore the anomaly, regarding it as a mistake or a stain of some kind. It is actually an example of anamorphosis—an image only visible from a very oblique angle.

Anamorphosis is widely used nowadays to make lettering and icons on roadway surfaces visible from the steep angle of a driver moving toward them (e.g., the bicycle at right), but it is also a clever way to put hidden images in pictures. When you stand off to the right side of The Ambassadors, up near the canvas, the “baguette” becomes visible as a skull (below). Skulls were commonly included in paintings of the period—especially paintings showing displays of wealth—as symbols of vanitas, or the transitoriness of life, reminding the viewer not to get too attached. We don’t know if Holbein was being deliberately mischievous with his anamorphic skull, but he was certainly showing off his skills with perspective (then a relatively recent invention), since anamorphosis requires considerable advance planning and mathematical precision.

Anamorphosis is widely used nowadays to make lettering and icons on roadway surfaces visible from the steep angle of a driver moving toward them (e.g., the bicycle at right), but it is also a clever way to put hidden images in pictures. When you stand off to the right side of The Ambassadors, up near the canvas, the “baguette” becomes visible as a skull (below). Skulls were commonly included in paintings of the period—especially paintings showing displays of wealth—as symbols of vanitas, or the transitoriness of life, reminding the viewer not to get too attached. We don’t know if Holbein was being deliberately mischievous with his anamorphic skull, but he was certainly showing off his skills with perspective (then a relatively recent invention), since anamorphosis requires considerable advance planning and mathematical precision.

Could anamorphosis help explain the elusive behavior of UFOs?

Could anamorphosis help explain the elusive behavior of UFOs?

The notion of portals or wormholes is popular nowadays in ufology, but the holographic hypothesis raises the possibility that UFOs could be sliding into and out of our (apparently) 3-D world from some high-energy Flatland—like a note slid under a door rather than a person opening it up and stepping through.

High-energy Flatlanders (or perhaps more likely, high-energy exotic technology capable of carrying ordinary 3-D beings from place to place via flat hyperspace) could be nearly invisible or completely non-understandable except when seen from a specific vantage point. This by itself is suggestive, given the fleeting, elusive, hard-to-verify nature of so many UFOs. Who knows?—Our eyes may pass over high-energy beings or technology all the time, but our visual system may generally ignore such anomalies because they make no sense or just blend into their surroundings.

I have long been troubled by the “higher dimensions” hypothesis, partly because it seems so unfair: If higher spacial dimensions reality exist, why would our cognitive faculties be so blind to them? What point is there for us to be only conscious of some of the dimensions available, in contrast to supposed higher dimensional beings who can dip into our impoverished reality occasionally and pity us? I am inclined to think that, with dimensions as with so many other things, less is more, and already our four dimensions are an embarrassment of riches. It may be our visitors (or their technology) that are “dimensionally challenged,” not us.

Somebody could write a sequel to Flatland, called Fatland, about spheres trying to come to grips with the appearance of a circle among them. Inevitably the Flatlander (circle) would appear merely as a line at first, and only widen out into a visible narrow oval and then finally a circle as it drew very close to an observer, but quickly it would dwindle to a mere line again as it receded. From most vantage points it would blend in or at least not be very distinct or salient, and there would be very little agreement among the spheres as to whether there was even anything there at all, let alone what its shape really was.

The Anamorphic Wedge

I want to briefly consider one further aspect of painterly anamorphosis that is suggestive for UFOs—this time in terms of the “control system” hypothesis advocated by Jacques Vallee.

As I said, anamorphic images can only be seen from a very restricted point of view—while one person sees the image, other people standing straight in front of the painting will see nothing, or will not know what they are looking at. Such images thus serve as kind of a wedge between consensus reality and the solitary, privileged viewpoint of the (intended) witness.

There are more aspects to this social-psychological effect of anamorphosis than first meets the eye.

Besides revealing itself to the selected witness, an anamorphic image also, in some sense, “frames” the rest of those viewers in his/her field of vision. Other people are suddenly seen standing there in front of the painting but blindly missing its point or its “true meaning.” In other words, anamorphosis not only displays itself as a hidden secret (thereby making the intended viewer feel special and chosen), it also highlights the ignorance and limited perspective of others in one’s social imaginary. Whether “the ignorance of the masses” is an accurate portrayal or not, it could be part of the intended take-away from a UFO encounter.

What’s more, social separation or isolation or even ostracism of the witness could be the intended effect, not just an unfortunate byproduct, of such an encounter. It’s at least a possibility to keep in mind, that UFOs, whatever they are, could be anamorphic phenomena aiming not only to manipulate or deceive witnesses but also to socially and psychologically isolate them, or separate them from the herd.

Anti-Anti-Tricksters

Over on UFO Conjecture(s), Rich Reynolds takes issue with the notion of “The Trickster” that is being increasingly invoked in ufology:

“Just as Christians and other religious aficionados think Satan or angels are real beings, ufologists like to use The Trickster as a real being, causing some UFO sightings or events. It’s an ignorant stance. Even as God is an iffy reality, The Trickster is so much more so. I would hope that readers here would refrain from stretching credulity to a breaking point by using The Trickster metaphor as an explanation for some UFO events.”

Reynolds is right that the Trickster concept can’t serve as an explanation. But at least in my reading of the topic, including George Hansen’s massive study The Trickster and the Paranormal or books tangentially invoking the concept, like Colm Kelleher and George Knapp’s Hunt for the Skinwalker, the term isn’t being used in a literalistic way to denote a “real being.” Rather it is being used, quite appropriately I think, as a shorthand term for a type of sentience or intention that seems to underlie a wide range of paranormal phenomena (ranging from UFOs to psychic experiences to hauntings) and that has a distinctly ironic, thwarting character. There’s no other term that quite fits the bill as well as “Trickster.”

I don’t see people using the term to mean a literal god or godlike being (a la Coyote or Hermes … or Satan, for that matter) whose purpose and mission is to screw with human affairs. The whole point of using the term is to avoid pinning UFOs’ origins down in all the ways they have been too narrowly pinned down throughout the history of ufology. It is far, far preferable to the term “extraterrestrials,” for instance—which truly is a completely distorting, biasing, pigeonholing rubric that has done untold damage to the field of ufology. (If I could beg ufologists to stop using any term, it would be that one, as there is no actual evidence, in all the millions of UFO encounters since the dawn of recorded history—and how could there be?—that the intelligences responsible, wherever they may occasionally say or imply they originate, are actually from other planets.)

Trickster is a useful term because it leaves the door wide open as to causation and origin while being descriptive of a very particular and peculiar phenomenology of many UFO experiences: the distinct and uncanny sense that there is not only a sentience underlying it but that this sentience can anticipate our actions in order to thwart our efforts at studying it. As an alternative, John Alexander offers the term “precognitive sentient phenomena”:

“The precognitive sentient phenomena concept suggests that there is some external controlling agent that initiates these events that are observed and reported. It appears as though that agent not only determines all factors of the event, but is already (i.e. precognitively) aware of how the observers or researchers will respond to any given stimuli. The agent can be considered like the Trickster that is always in control of the observations. Every time researchers get close to an understanding of the situation, the parameters are altered or new variables are entered into the equation.”

Precognitive sentient phenomena is a good term, but it is a mouthful. Trickster is a handy placeholder and shorthand … that is, pending some kind of a real explanation.

The Trickster does not refer simply to life’s tendency to have ups and downs, as Reynolds suggests in his post, but to something much more specific. Signaling as it does a nod to archetypal psychology, the term registers the possibility (at least) that these phenomena may be linked to our own consciousness or unconscious in ways we don’t yet fathom. Plus, the fact that world mythologies and folklore have always included beings who personify precisely these “precognitive sentient” qualities that are seen again and again not only in ufology but also in parapsychology is itself highly suggestive of something … and I don’t think anyone who uses the term precisely knows what, but it’s a useful fact to keep in the back of our minds.

That said, however, it is good to be wary of such placeholder terms, because they do sometimes end up sticking around long past their due date—and this is especially true of other terms associated with Jungian psychology. “Synchronicity” is such a term, which did not actually denote an original concept (Paul Kammerer had already described essentially the same thing with his notion of “seriality”) and has never been useful in helping us theorize ESP. In a future post I will argue that parapsychologists and “synchromystics” should avoid using Jungian vocabulary, because many of his once-novel terms and metaphors have now become conceptual straightjackets limiting our thinking.

I’m not worried about The Trickster, however, because its application to ufology and other unexplained phenomena is relatively new and harmless, and it’s much better than constantly talking about “ET.” But if he’s still hanging around in 10 or 20 years, that may indeed start to get awkward.

The Biggest Bullshit: David Lynch and the Cowboy

Well, there are many kinds of films. Most of them, nowadays, don’t demand much thinking. That makes me very, very upset. It makes me upset that they think the audiences have grown unused to thinking and that they only want things spelled out for them, in a platter. That’s bullshit, and a big one. People love to think. We are all detectives. We love to observe, we love to deduce. It is great to pay attention. We have a lot of fun this way. — David Lynch, on Mulholland Drive

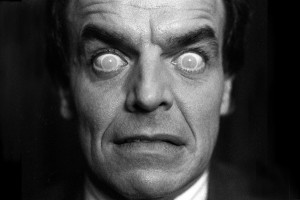

You’re not thinking. You’re too busy being a smart-aleck to be thinking.—The Cowboy, Mulholland Drive

Suffering comes from the energy we perpetually expend in keeping up appearances of knowing, the constant knowing attitude we take toward life. Been there, done that, same old same old. It becomes the armor we clothe ourselves with—projecting this image that I know who I am, and why I’m here, and what I’m doing. In the postmodern world, this attitude has become institutionalized in sarcasm, ironic detachment, snarky jadedness, and (to use the Cowboy’s anachronistic expression) being a smart-aleck.

How true, the words of the Cowboy: We go through our lives taking a too-cool-for-school, smart-alecky attitude toward the givens of our lives, and as a result, fail to think and pay attention.

The Zen masters tried to get their pupils to stop knowing, to un-know, and they had different ways of doing it. The Soto school made the monks just sit, stop imagining they had anything more important to do or anyplace better to be. It’s much tougher than it sounds. It appealed (and still appeals) to students who naturally have calm, relaxed, patient minds. The Rinzai school, on the other hand, used story-puzzles, or koans, and appealed (and still appeals) to active intellects who naturally can’t resist interpreting and solving puzzles. Koans invite intellectual analysis, but at a certain point—weeks or months later—the intellect runs aground, and suddenly the monk finds himself or herself in a transfigured place.

“Rinzai” is how the Japanese pronounce the name of the 9th-Century Chinese master Lin-Chi. David Lynch says of his film Mulholland Drive that “We are all detectives. We love to observe, we love to deduce.” He understands people’s love of interpretation, of playing detective, and I would bet money he created Mulholland Drive as a deliberate koan. If meditated upon at sufficient length, it can take you to a place beyond interpretation. But we have to go through that effort of intellectual interpretation in order to awaken, to transcend. When we do that, we find ourselves not in a meaningless depressing world but in an enlarged, more immense, more spacious place that is full of possibility and importance and power.

I wrote in another post that Mulholland Drive specifically lures you to distinguish the “dream part” from the “real part” of the main character Diane’s (Naomi Watts’) story. Innumerable clues are there to indicate that the first two-thirds of the film, right up until the Cowboy’s “Hey pretty girl, time to wake up,” are meant to be seen as a textbook wish-fulfillment dream sequence that scrambles, rearranges, and transforms all the elements of Diane’s depressing “real-life” predicament—that she has hired a hit-man to kill her glamorous actress lover Camilla (the amnesic dark-haired “Rita” in the dream) after the humiliation and heartbreak of the latter’s rejection of her and announced engagement with a famous film director, Adam Kesher.

After a couple viewings of Mulholland Drive, this interpretation emerges pretty clearly and naturally. The film has thus been compared to The Wizard of Oz: The long dream core of the film consists of elements from the main character’s real life but jumbled and transformed according to dream logic, to create a fantasy that removes all the pains of the dreamer’s existence, erasing all of her guilt, and giving her all the things she wishes for. Textbook Freud.

Almost.

Once you’ve performed this “natural” interpretive procedure that the film invites, and followed it to its conclusion, you discover that you’ve been led into a trap: When you put the final piece in place, the film shows a message that was not visible before. This is the real genius of a film that is already genius on every more superficial level.

The key to the hidden message is the Cowboy.

The first time we (the audience) see the Cowboy is when he berates Adam Kesher for being a smart-aleck and for thinking he can have any woman he wants as the lead in the film he is making. He also says “You’ll see me once more if you do good, twice if you do bad.” Although it is addressed to the buffoonish Kesher, we likely take this promise as meant for “Betty,” the “real world” Diane, whose story this all really seems to be.

But … if we follow Diane’s “real” chronology as reconstructed in the aforementioned Wizard of Oz interpretation, this dream appearance is actually the second time Diane sees him—the first having been when he briefly walks through the room at the party where Adam and Camilla (dream Rita) announce their engagement. Diane’s dream has transformed this single fleeting “day residue” into one of two central psychopomps in the film (the other being the Club Silencio emcee), and her unconscious creates the dream of the Cowboy chastising and threatening Kesher that he’ll appear twice more if he does bad. This means Diane, the “real” subject of the movie, encounters the Cowboy only once more after this warning before she dies: When he appears at the end of her dream, in her doorway, and tells her it’s time to wake up.

We could interpret this as indicating that Diane has done well … done well, perhaps, by killing herself—after all, her life has become untenable, as she has had her former lover killed and the detectives know, and are knocking on her door. There is no other way out for her but to blow her brains out.

But let’s face it: If it isn’t Diane who’s being bad, then it is us, the viewers, who are being bad, since we do see the Cowboy two more times after his first appearance at the Corral.

Gulp. What did we do wrong? How are we being bad?

The Cowboy has already told us plainly: By being smart-alecks. Smart alecks don’t think they need to pay attention and think about what’s being said to them, because they think they already know, already have things figured out. But of all films, Mulholland Drive is designed as a big demonstration that no, we (we audience members, we human beings) do not have it figured out, and we are in fact very poor learners.

Lynch has said that one of his earliest films, a short called Alphabet, was about the “anxiety of learning.” This theme is clearly alive and well in Lynch’s late works too: Like the characters in his films, we are made to feel dumb by what he shows us. The Club Silencio emcee assures us that there’s no band, that it’s all a recording, and yet we are surprised when a trumpet player stops fingering his instrument and the music continues. And just minutes later, as Rebekah Del Rio sings “Crying,” we are just as amazed when she collapses on stage and her recorded voice continues to sing as we were when the trumpet player stopped playing.

So the Cowboy and the emcee at Club Silencio are both stand-ins for Lynch the Master, Lynch the teacher, who like his close namesake Lin-Chi famously just barked at or struck his pupils get them to see the light.

In Mulholland Drive, we are being shouted at by a teacher whose impatience is, despite his ferocity, infinitely compassionate. This is because his works have a real-world purpose. They are initiations: He is trying to transmit a bit of learning that has been important to him and that he really wants to share with us. We won’t get it as long as we are being smart-alecks, so he is in effect slapping us in the face to get us to stop that behavior long enough to see what he is talking about.

I explained in my earlier post that what he’s trying to get us to see is that there’s no “real” and no “not real” in the film—they are fundamentally the same, just following different narrative rules, just shot in different styles, to lead us into the trap of picking them apart and distinguishing them. It’s like Lynch has taken us on this long, very enjoyable journey, getting us to play detectives (who are, as we speak, knocking loudly on the door), only to lead us to a back alley where we are shown Rene Magritte’s painting The Treason of Images—with a picture of a pipe on a school blackboard and the caption “This is not a pipe”: There’s no “dream” and no “reality” in Mulholland Drive—it’s a movie, stupid. All parts are equally fictional; nothing is more real than anything else. It’s all equally unreal. It’s all a recording.

I explained in my earlier post that what he’s trying to get us to see is that there’s no “real” and no “not real” in the film—they are fundamentally the same, just following different narrative rules, just shot in different styles, to lead us into the trap of picking them apart and distinguishing them. It’s like Lynch has taken us on this long, very enjoyable journey, getting us to play detectives (who are, as we speak, knocking loudly on the door), only to lead us to a back alley where we are shown Rene Magritte’s painting The Treason of Images—with a picture of a pipe on a school blackboard and the caption “This is not a pipe”: There’s no “dream” and no “reality” in Mulholland Drive—it’s a movie, stupid. All parts are equally fictional; nothing is more real than anything else. It’s all equally unreal. It’s all a recording.

If we need confirmation, only note the absence of a “real world” counterpart of the mysterious blue box. It is opened in the “dream” by the strange blue key. A mundane version of the blue key is conspicuous in depressed Diane’s apartment at the end, and in a flashback, it is shown to her by the hit man in Winky’s diner, who says she’ll find it “at the place I said” when he has finished his job of offing her lover Camilla (dream Rita). Diane asks, naively, “What does it open?” The hit man gets a quizzical look and just laughs and shrugs at her dumb literal-mindedness: The point is, the key is a message, not actually a functional key that opens anything. There’s no “real” box … just like there’s no band.

A teacher of Tibetan dream yoga, Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche, writes that “ultimately the meaning in the dream is not important. It is best not to regard the dream as correspondence from another entity to you, not even from another part of you that you do not know. … It may sound strange, but this idea of meaning must be abandoned before the mind can find complete liberation. … Instead penetrate to what is below meaning, the pure base of experience.”

I don’t know if Lynch has ever said it explicitly, but I suspect he would say it, so I’ll venture: Movies, like dreams, can seduce and delight us with their obvious and hidden meanings, but ultimately they should take us to a place beyond meaning. Have fun decoding them, but don’t think that’s enough, that it is just about proving your cleverness; learn to see through the movie to the Real. Lynch’s later movies invite us to interpret and find meaning, but they are koans—traps meant to take us to a higher place. Mulholland Drive is his most exquisitely designed trap.

***

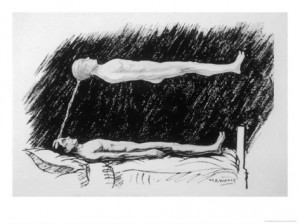

Menopausal Mystics in Space

In my “Psychic Astronauts” post several months ago I thought I was being somewhat original by imagining a hypothetical cost-efficient scenario for our future exploration and colonization of space—one that made use of the interesting (at-this-point-unproven, admittedly highly controversial) notion of nonlocal mind. Specifically, I suggested that highly trained psychic explorers could remote view distant planets, visit them astrally (or, to be pedantically precise, etherically), telepathically manipulate organisms there across vast epochs of their evolutionary history (remembering that nonlocality applies to time as well as space), and then psychically inhabit or “possess” specially bred remote host vessels.

Faxing ourselves across space and time in this fashion sounds convoluted and crazy … but basically, if there is any truth to the claims of psychic researchers, remote viewers, and mystics since time immemorial, then there’s really nothing (other than our own present lack of development of those capacities) that would inherently prevent such a possibility. A project to train hundreds or thousands of psychic astronauts would be far less costly (and time consuming) than even a mere manned Mars mission, let alone a Star Trek-style space program.

Faxing ourselves across space and time in this fashion sounds convoluted and crazy … but basically, if there is any truth to the claims of psychic researchers, remote viewers, and mystics since time immemorial, then there’s really nothing (other than our own present lack of development of those capacities) that would inherently prevent such a possibility. A project to train hundreds or thousands of psychic astronauts would be far less costly (and time consuming) than even a mere manned Mars mission, let alone a Star Trek-style space program.

I was certainly aware that this plan mashes together various ideas that have all appeared in science fiction—especially from the more open-minded, less slavishly scientistic era of pulp. H.P. Lovecraft, with his telepathic slumbering Old Ones, springs immediately to mind. (More recent scenarios of prehistoric alien visitation/intervention—such as those of Erich von Daniken, Zechariah Sitchin, and lately Ridley Scott—are more mundanely nuts-and-bolts, using actual spaceships, etc., in keeping with the dogmatic materialism of our day.) Until today, though, I had no idea of the true pedigree of the concept of psychic astronautics.

In a landmark archaeology of what could be called ‘ancient psychic astronaut theory’ on his blog The Secret Sun, Christopher Loring Knowles reveals that the Theosophical writings of Alice Bailey, especially her 1922 book Initiation: Human and Solar—supposedly channeling a Tibetan Ascended Master named “Djwal Khul”—describe precisely the scenario I sketched, albeit in reverse: the psychic colonization of Earth (via astral travel) by beings from the Sirius star system, who shaped ape-men into human beings to serve as receptacles for their consciousness.

Knowles is less interested in the crazy scenario than in its literary borrowing (too weak a word) by Lovecraft himself. In a point-by-point comparison, he shows that the parallels between Lovecraft’s “Call of Cthulhu” and Bailey’s channeled revelations about Earth’s distant past are so close as to be essentially plagiarism. Knowles suggests that the Darwinian Lovecraft originally wrote his dark novella in 1926 as a parody of the Theosophist’s occult ideas, but that he then carefully omitted all mention of Bailey’s book to his friends, not wanting to betray the unoriginality of his basic (and, in his hands, pretty damn cool) cosmic premise.

Though it doesn’t really dim my appreciation for Lovecraft, I love Knowles’ discovery. He notes that Theosophy, with its violet-hued astral planes and Ascended Masters in flowing gowns, was written mainly for an older, female audience. Terence McKenna (for whom the real ancient astronauts were the Stropharia cubensis mushroom) derisively referred to this demographic as “menopausal mystics.” Although there is a lot that is unoriginal, deeply questionable, and by modern standards rather un-awe-inspiring in the Theosophists’ cosmological visions, there is also much of value in their writings—particularly if you are open minded to the idea of siddhis, psychic abilities, and human potential in general. And they certainly supplied plenty of cool and original ideas to a generation of sci-fi writers who were less fetishizing of technology and more open-minded about the future (and past) of consciousness than many present-day writers.

Wouldn’t it be strange, and sort of wonderful, if mankind’s real future in space turned out to more closely resemble the channeled revelations of an early 20th Century menopausal mystic than the promethean hi-tech visions of Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick, or Ridley Scott?

Lost and Found in Psychic Space: Airplanes, Aviators, and ESP

I’m fascinated by how aviation and missing planes are so often linked, in one way or another, to ESP phenomena. The ongoing, frustrating search for Malaysian Flight 370 seems like the perfect opportunity to write down some thoughts about this strange nexus.

There’s a long history of psychics being enlisted (or volunteering) to search for lost planes, for one thing. One of the best-known successes of the early operational remote viewing work at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) was the successful location of a lost Soviet spy plane in the African jungle using the talents of viewers Gary Langford and Rosemary Smith. The annals of remote viewing (as described in Jim Schnabel’s excellent history of the subject) include other successful searches for missing aircraft. At Fort Meade for example, Ken Bell accurately pinpointed the site of a military crash in Virginia (even getting the name of the mountain, “Bald Knob”). On another occasion, he successfully remote-viewed the burned wreckage of an American helicopter that had crashed high in the Andes in Peru, killing the crew.

So it is to be expected that today’s most accomplished remote viewers and other psychics are being recruited to search for the missing Malaysian jet. Uri Geller, quite naturally, says he has been asked by a “substantial figure” for help in the search. Geller is more famous for telekinetic and telepathic feats than for clairvoyance, but he made his fortune map-dowsing for mineral and oil deposits—a skill one would think is not too different from viewing lost objects at a distance. He has not pointed to an actual location for the presumably downed plane, that we know of. But according to The Anomalist, remote viewer extraordinaire Joe McMoneagle, one of the original Fort Meade team, has also been tasked in the search; he says he has “duly reported” his findings.

When scientific or military professionalism and rigor are not involved, psychic attempts to locate missing aircraft are, as one can imagine, often not only unsuccessful but even tragically misleading. In his thorough and riveting account

When scientific or military professionalism and rigor are not involved, psychic attempts to locate missing aircraft are, as one can imagine, often not only unsuccessful but even tragically misleading. In his thorough and riveting account of the Uruguayan rugby team lost in the Andes in 1972, Piers Paul Read documents the desperate families’ use of psychics to help in the search. A Belgian clairvoyant, Gerard Croiset Jr., was recruited, and although he described several specific details that ultimately proved accurate (such as a nearby sign reading “Danger” and the physical appearance of wreckage itself), he insisted the plane went down near a lake over 80 miles south of the crash site—resulting in much money, time, and effort being wasted searching in the wrong place.

The sad irony is that the first psychic consulted by parents of two of the lost boys, a dowser in a poor Montevideo neighborhood, turned out to have precisely pinpointed the location of the downed plane. Unfortunately the area he picked had already been overflown on early search flights and was, in any event, deemed too dangerous and remote for further searching. (Read’s book Alive contains more tantalizing ESP-related tidbits, including accurate premonitions of imminent rescue by some of the survivors; the more recent documentary Stranded includes survivors’ fascinating accounts of their near-death experiences during an avalanche that struck 16 days into their ordeal and killed 8 of their companions.)

Then of course there’s Amelia Earhart.

When Earhart went missing in her Lockheed Electra in 1937, her husband George Palmer Putnam was inundated with mail from psychics and others who insisted they knew where Earhart’s plane had gone down, had had dreams of her, or had actually communicated with her psychically in the days and weeks following the disappearance. A 1940 article in Popular Aviation, which has been made available as a pdf on the Earhart Project website, is a great read and another fascinating account of the paranormal giving hope to those desperate to find their loved ones but also hopelessly muddying the waters of an investigation of a lost flight.

The Popular Aviation article only details a few of the examples of the messages Putnam received, unfortunately, but the ones described are particularly interesting in light of the unfolding (but lately stalled due to legal problems) efforts of the The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) to piece together Earhart’s last days and recover remains of the Electra. From what one can glean from the 1940 article, psychic consensus seemed to be that she and her navigator Fred Noonan went down somewhere north of Howland Island—not south, in the direction of Nikumaroro atoll, where TIGHAR has found tantalizing evidence that the flyers actually ended up. However, people who corresponded with Putnam said that they knew she had survived the crash and was on an island or atoll, and provided scenes that correspond to the picture being assembled by TIGHAR—that the famed aviatrix and her companion survived, possibly for a few weeks, before perishing (probably from dehydration).

The Popular Aviation article only details a few of the examples of the messages Putnam received, unfortunately, but the ones described are particularly interesting in light of the unfolding (but lately stalled due to legal problems) efforts of the The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) to piece together Earhart’s last days and recover remains of the Electra. From what one can glean from the 1940 article, psychic consensus seemed to be that she and her navigator Fred Noonan went down somewhere north of Howland Island—not south, in the direction of Nikumaroro atoll, where TIGHAR has found tantalizing evidence that the flyers actually ended up. However, people who corresponded with Putnam said that they knew she had survived the crash and was on an island or atoll, and provided scenes that correspond to the picture being assembled by TIGHAR—that the famed aviatrix and her companion survived, possibly for a few weeks, before perishing (probably from dehydration).

An interesting angle in this case is that Earhart herself was an accomplished psychic—although she publicly downplayed her talents in an era that was just as rationalistic and skeptical as ours. She had a particular knack for finding missing aircraft. As described by two newspaper columnists quoted by David K Bowman:

“Officials at first were inclined to laugh at Miss Earhart’s psychic messages. But her accuracy now has them mystified. When a United Airlines plane was lost just outside of Burbank, Calif. Dec. 27, Miss Earhart called the United Airlines office and told them to look on a hill near Saugus, a little town north of Burbank.

“There the wreckage was found.

“Again when the Western Air Express plane carrying Mr. and Mrs. Martin Johnson crashed Jan. 12, Miss Earhart reported the plane to be near Newhall, 15 miles north of Burbank, where it was found.

“In the earlier crash of the Western Air Express in Utah, Miss Earhart had a vision to the effect that the bodies of the dead had been robbed by a trapper. Two days later, a trapper near Salt Lake City reported finding the wreckage, but then suddenly disappeared without giving the location of the plane.”

There seems to be a link between a penchant for real-world flying and psychic aviation. For example, decades after his historic trans-Atlantic solo flight, Charles Lindbergh admitted in a memoir that during the 33-hour journey, during which he did not dare actually fall asleep, he experienced a hypnagogic, dissociative state in which he felt his body, soul, and spirit separate—what we might now call an out-of-body experience. During this experience, the flyer perceived and communicated with angelic beings accompanying him in his plane. The encounter left him with a lasting interest in the afterlife and immortality.

A more recent example is the popular author and aviator Richard Bach. After the CIA withdrew funding from the SRI project in the late 1970s (wanting to distance itself from questionable research in the aftermath of revelations about MK-ULTRA and other projects), Hal Puthoff and Russell Targ became increasingly creative in seeking support for their research at SRI. One person they sought out for possible help was Bach, whose bestseller Jonathan Livingston Seagull seemed (to Targ at least) like an account of an out-of-body experience—a phenomenon with strong continuity with remote viewing. On the hunch that Bach might be interested to participate in some psychic research himself and perhaps give some money to SRI, Targ and Puthoff invited Bach to California to take part in some experiments.

The writer proved quite talented. For example, in one out-bounder experiment described in Targ and Puthoff’s book Mind-Reach, he gave a very accurate physical description of the interior of a modern A-frame Methodist church and its altar—although in a case of “analytical overlay” biasing his interpretation, Bach thought the altar with the cross behind it looked like (appropriately enough) an airport ticket counter with a fleur-de-lis airline logo. Jacques Vallee, SRI Arpanet pioneer and friend to the remote viewing program, describes in his journals that he arranged to have a computer terminal installed in Bach’s Florida home, where Bach participated in a networked, cross-country remote viewing experiment in which he was remarkably accurate in describing an assortment of minerals chosen by a geologist.

The longest-distance psychic experiment ever conducted by an aviator, or anybody, is no-doubt that conducted by astronaut Dr. Edgar Mitchell aboard Apollo 14 in 1971. Like previous aviation pioneers, Mitchell had a profound mystical experience during his journey; but quite apart from this, he had a longstanding interest in ESP and, at four predetermined times during the mission, telepathically transmitted randomly selected Zener symbols (the type used in the classic Rhine experiments) to a small group of psychics back on Earth. He reported that there were 51 correct responses out of 200 total—slightly better than chance (there are 5 symbols in a Zener deck, so 40 correct responses would be predicted by chance). It is typical of the interesting but rather uninspiring positive results produced by classical psi research before the SRI era.

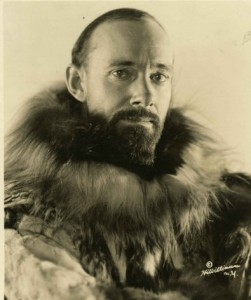

The great precedent for Mitchell’s long-distance telepathy experiment, however, is far more inspiring. In 1938, a dashing, larger-than-life aviator and all-around hero explorer, Sir George Hubert Wilkins (left), volunteered on a dangerous mission to the arctic to search for a lost Russian plane and hopefully rescue the crew. Before he departed, he arranged to mentally send updates of his adventure at regular times each week to a New York writer with an interest in ESP named Harold M. Sherman. Sherman, for his part, recorded his impressions and had them notarized to prove that no cheating had transpired. Wilkins and Sherman documented the results in their classic book Thoughts Through Space

The great precedent for Mitchell’s long-distance telepathy experiment, however, is far more inspiring. In 1938, a dashing, larger-than-life aviator and all-around hero explorer, Sir George Hubert Wilkins (left), volunteered on a dangerous mission to the arctic to search for a lost Russian plane and hopefully rescue the crew. Before he departed, he arranged to mentally send updates of his adventure at regular times each week to a New York writer with an interest in ESP named Harold M. Sherman. Sherman, for his part, recorded his impressions and had them notarized to prove that no cheating had transpired. Wilkins and Sherman documented the results in their classic book Thoughts Through Space.

The records of Sherman’s and Wilkin’s experiment are remarkable, and resemble the sometimes astonishing accuracy of later CIA and military clairvoyants when real-world events and locales, rather than boring randomly generated cards, are involved. Reading the book through the lens of hindsight, it becomes clear—as it even became clear to the participants themselves when Sherman’s impressions were checked against Wilkins’ periodic bulletins—that “thoughts through space” did not accurately characterize the signal line through which Sherman received his information. Wilkins admitted he was often too busy, or simply forgot, to send his mental messages at the appointed times, but this did not prevent Sherman from obtaining detailed, usually accurate impressions of Wilkins’ activities and whereabouts.

In other words, Sherman was engaged precisely in remote viewing, not telepathy or (to use Upton Sinclair’s term) “mental radio.” Had it occurred to either of the experimenters to have Sherman psychically search for the missing Russian plane himself and thus serve as Wilkins’ guide rather than just his remote “receiver,” Wilkins’ mission may have been more successful than it was—but that would have required a paradigm shift in parapsychological thinking that was still over three decades off.

The experiment with Sherman is, to my knowledge, the first and last time Wilkins participated in an ESP experiment. Sherman, however, went on to write several interesting popular guides to developing ESP powers, not to mention numerous pulp sci-fi novels. In fact, he is a strangely absent figure in the nexus of psychic abilities, human potential, and sci-fi so densely chronicled by Jeffrey Kripal in his great book Mutants and Mystics.

In any case, there seems to be something fascinatingly archetypal about this nexus of aviation and ESP. Flying through air and space—and the extreme lengths to which one can get lost doing so—seem almost like a hieroglyph, in mundane 4-D reality, of how far one can travel and also get lost in the dimensionless space of consciousness and psychic abilities (or dis-abilities). Time will tell if and how this archetype plays out in the story of Flight 370. As The Anomalist notes, there may be little hope of anyone’s (even Geller’s or McMoneagle’s) ESP-derived insights having an impact on that search, given that there are bound to be hundreds or more intuitives, psychics, remote viewers, etc. giving their own conflicting reports. If I were one of the “authorities” involved, this is one reason I would be cautious following leads obtained from the paranormal information superhighway, however tantalizing they may be.

Postscript: Wilkins, The Nautilus, and SRI

Oddly enough, it is through an interesting mix of coincidence and distorted memory that Wilkins’ and Sherman’s Thoughts Through Space experiment may have had a decisive influence on the later research at SRI and the whole history of remote viewing.

According to Jim Schnabel, a 1960 report in the French magazine Science et Vie claimed that the nuclear submarine USS Nautilus had conducted a telepathy experiment on its historic voyage under the North Pole in 1958. Upon closer scrutiny, the claim proved to have been either fraudulent or based on fabricated information, but nevertheless it spurred anxiety on the part of the Soviets that the United States was developing psychic abilities for military application, and they began pouring money into paranormal research. It was this development, reported in Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain in 1970, that in turn triggered anxiety in US intelligence and military circles that we may lose the psychic arms race if we didn’t fund such research ourselves. Hence SRI, and the subsequent developments at Ft Meade and elsewhere.

According to Schnabel, the source of the Science et Vie story that started the false rumor of US psychic research in the 1950s is unknown—it was either a hoax or may have been a deliberate disinformation ploy to get the Soviets to waste their money on paranormal woo. But I suspect the story could actually have arisen from a more innocent case of distorted recollection by someone involved in the magazine article or their sources, because it involves a fascinating, tangled knot of coincidences.

Several years before his 1938 arctic aviation expedition with its telepathy component, Wilkins had himself attempted to reach the North Pole underwater, in a decommissioned American submarine O-12 that he had leased from the Navy and rechristened, wait for it, The Nautilus. I think it would have been all too easy for someone to later conflate the various adventures of this dashing polar explorer (who sometimes engaged in telepathy experiments) with the news of the first actual polar crossing by a (this time nuclear) submarine, also named Nautilus, in 1958.

To make things more confusing, the nuclear Nautilus‘s first commander was named … Wilkinson.

Kafka and the UFO Gnosis

Rich Reynolds has a nice piece over on UFO Iconoclast comparing ufology to Samuel Beckett’s existentialist play Waiting for Godot. It’s a really apt comparison: The two main characters wait around for a person who is never going to come, and this waiting keeps them from becoming fully conscious and responsible for their lives.

A similar comparison I would make is to practically everything by Kafka. Ufology is murky, increasingly maddening, and you are perpetually unclear where you stand; you seem to be on the brink of figuring out some piece of the puzzle, and then you realize you are at the back of a line of aging people who have been standing in that same line their whole life, clutching essentially the same speculations in their dusty binders and briefcases, still awaiting confirmation from some authority that they have made progress though they have essentially gotten nowhere.

The whole idea of “disclosure,” particularly, reminds me of the central parable of The Trial. A man from the country comes before the Door of the Law, wanting access, but he is stopped by a doorkeeper who makes him wait, although not without accepting bribes “just so you don’t feel you’ve left anything untried.” The man waits his whole life, and finally, as he’s about to die, he finally asks the doorkeeper, “Why, if this is the Door of the Law, has no one else come seeking entry all this time?” To which the doorkeeper says, “Because this door was meant for you alone. I’m now going to shut it.” A brilliant light shines from deep within the edifice as the door is shut.

I see it as a sort of Gnostic lesson having to do with experience versus faith. The only important knowledge is experiential self-knowledge, and it can’t be thought of as coming from outside oneself, in the form of a religious or secular authority (such as the government, the UFOs themselves, or any other “subject presumed to know”—to borrow a term from psychoanalysis). You’ll get nowhere until you include the knower (you, the man from the country) in the known; the door, the light shining through it, and even the doorkeeper and especially the man himself are all part of the same picture.

I suspect that, when it comes to UFOs, what we need to know is already right in front of us, and the whole scene of “authorities keeping knowledge from us” is a bit of self-parody within a larger riddle (or koan) addressed to us, not the thing keeping us from cracking it.

We need to recognize ourselves as knowers. Dwelling on the idea that truth is “out there” is a way we overlook that explosive gnosis until it is too late.

____

Psychic Astronauts: Remote Viewing, Space Exploration, and UFOs

The emptiness of Fermi’s Paradox as an argument against ETs rests, I think, on the unlikelihood that advanced technological civilizations would ever explore or colonize their universe in the flesh. I’ve suggested here that the “reach” of ETs through space, and that of our own human or machine descendents, will be via Von Neumann probes gathering and collecting potentially infinite amounts of information for use and enjoyment back home. But there are other, not incompatible possibilities that, if we are to be suitably broad minded, we should also consider. These possibilities rest on a series of very big “ifs,” admittedly, but they are worthwhile (and way fun) to think about.

One of these ifs—which actually seems to be becoming less controversial in our day—is ESP. As outrageous as it remains to committed materialists—and I’ll admit it didn’t settle well with me either until I started paying serious attention to the literature—there is ample experimental evidence (quite apart from ample testimony of psychonauts and mystics since time immemorial) that knowledge may indeed transcend apparent limitations of matter, space, and time. According to a few serious scientific thinkers on this topic like Russell Targ and Dean Radin, consciousness is nonlocal. The CIA-funded remote viewing research of the 1970s and 80s at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), for instance, shows that distance is no obstacle for talented clairvoyants; the experiments conducted at SRI by Targ and Hal Puthoff clearly indicate that Psi effects don’t obey an inverse square law like electromagnetic radiation or any other known physical force. Skilled remote viewers seem to be able to accurately view targets on the other side of the planet or within an electromagnetically sealed chamber as readily as they can view something in a sealed envelope in the same room.

One of these ifs—which actually seems to be becoming less controversial in our day—is ESP. As outrageous as it remains to committed materialists—and I’ll admit it didn’t settle well with me either until I started paying serious attention to the literature—there is ample experimental evidence (quite apart from ample testimony of psychonauts and mystics since time immemorial) that knowledge may indeed transcend apparent limitations of matter, space, and time. According to a few serious scientific thinkers on this topic like Russell Targ and Dean Radin, consciousness is nonlocal. The CIA-funded remote viewing research of the 1970s and 80s at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI), for instance, shows that distance is no obstacle for talented clairvoyants; the experiments conducted at SRI by Targ and Hal Puthoff clearly indicate that Psi effects don’t obey an inverse square law like electromagnetic radiation or any other known physical force. Skilled remote viewers seem to be able to accurately view targets on the other side of the planet or within an electromagnetically sealed chamber as readily as they can view something in a sealed envelope in the same room.

According to a former Congressional Aide interviewed by filmmaker Vikram Jayanti for a new, fascinating BBC documentary on Uri Geller’s spy work for the CIA and other intelligence agencies, the research made famous by Targ and Puthoff and project Star Gate continues now, but in the “deep, deep black”—interestingly enough, having been driven into the underground not because it was scandalous to mainstream science but because it conflicted with the Fundamentalist Christian theology of certain defense higherups in the 1980s and 90s. One wonders whether, decades later, this “deep black” research is still confined to remote viewing terrestrial targets?

Pat Price, the star remote viewer in Targ and Puthoff’s research at SRI, commented that he was “potentially omniscient in space and time” (see Targ and Puthoff’s Mind-Reach). And famously in the annals of remote viewing, psychic Ingo Swann, while at SRI, viewed the rings of Jupiter before they were discovered by the Pioneer 10 probe; and according to his bizarre memoir Penetration, he psychically saw structures on the moon similar to those allegedly photographed by the Apollo missions and that serve as fodder for various space anomaly websites. Whether or not Swann was accurate in the latter moon observations, Swann seems to have been the first to seriously attempt psychic astronautics in modern times—although mystics in the past such as Emanuel Swedenborg have also claimed to visit other worlds and communicate with their inhabitants.

Picture a room full of highly trained Ingo Swanns, given coordinates for one of the habitable-zone super-earths around Gliese 667c to image; each one receives the same coordinates, and from their collective viewings a rough consensus is reached about that sector’s topographic features or interesting biology (if any); then they move onto the next coordinates, ultimately creating a rough map of the whole planet; then they move on to the next planet … and so on. Is this the future of space exploration? Are such projects already being conducted in secret by government contractors or by NASA itself?

Picture a room full of highly trained Ingo Swanns, given coordinates for one of the habitable-zone super-earths around Gliese 667c to image; each one receives the same coordinates, and from their collective viewings a rough consensus is reached about that sector’s topographic features or interesting biology (if any); then they move onto the next coordinates, ultimately creating a rough map of the whole planet; then they move on to the next planet … and so on. Is this the future of space exploration? Are such projects already being conducted in secret by government contractors or by NASA itself?

And by extension, could an ET psychic space program be behind many close encounters?

Psychic Aliens

Encounters with “aliens” (or whatever they are) frequently have a psychic component, as Jacques Vallee has always stressed. That alien intelligences interact with humans psychically is a common theme also in the sci-fi and comic book collective unconscious, as Jeffrey Kripal has shown in his book Mutants and Mystics and as Christopher Loring Knowles has described on his phenomenally interesting blog The Secret Sun.

There is also the vast, weirdly consistent literature on experiences with Ayahuasca, Psilocybin, and other DMT-based entheogens: Users of these drugs consistently encounter alien beings that resemble those familiar from the UFO literature and/or enter a realm seething with alien intelligence. DMT researcher Rick Strassman has argued that the resemblance of DMT experiences to UFO abductions may not be a coincidence. The easy, respectably materialist position here is that of course it’s not a coincidence: It’s all in the drug-user’s (or contactee’s) head. But Strassman himself remains open-minded that the reality could be something more interesting and complex—that the intelligences might be authentic and that DMT may be facilitating access with the noetic realm or wavelength where they reside or through which they attempt to interact with us.

There is also the vast, weirdly consistent literature on experiences with Ayahuasca, Psilocybin, and other DMT-based entheogens: Users of these drugs consistently encounter alien beings that resemble those familiar from the UFO literature and/or enter a realm seething with alien intelligence. DMT researcher Rick Strassman has argued that the resemblance of DMT experiences to UFO abductions may not be a coincidence. The easy, respectably materialist position here is that of course it’s not a coincidence: It’s all in the drug-user’s (or contactee’s) head. But Strassman himself remains open-minded that the reality could be something more interesting and complex—that the intelligences might be authentic and that DMT may be facilitating access with the noetic realm or wavelength where they reside or through which they attempt to interact with us.

Abduction experiences with and without the use of drugs point to at least the possibility of alien psychic astronauts visiting us in the comfort of our living rooms, from the comfort of their living rooms, via a sort of cosmic noetic superhighway—which may be the same thing as the Nous of Gnostic and Hermetic mysticism or the Akasha of the Theosophical writings. Psilocybin prophet Terence McKenna, who routinely encountered alien-like “machine elves” (and whose Amazonia experience in 1971 vividly foreshadowed many of the extraterrestrial Gnostic themes and insights of Phillip K. Dick’s “2-3-74” experience a couple years later) would certainly agree with this idea; he suggested that Stropharia cubensis mushrooms may themselves be a plant-based ET colonization project, spores traveling through space and creating nodes in what we might now call an Astral Internet.

Think Nonlocally, Act Remotely

The notion of a nonlocal universe has also been called the “holographic universe” because any small fragment of a holograph contains the whole within it. Psi experiences are a scientific (though committed skeptics will always call them pseudoscientific) idiom for describing experiences of a realm that elsewhere and in other times have been called sacred or mystical, and there seems to be considerable overlap between these sorts of telepathic or clairvoyant capacities and other seemingly more farfetched experiences like astral projection or out-of-body (OOB) travel.

The latter phenomena are to my knowledge less well documented scientifically (except in the controversial near-death-experience literature), but they are equally well-assented by thousands of years of anecdotal accounts by yogis, shamans, and ordinary “gifted” individuals. The Theosophic tradition refers to travel in the Astral Plane, although it is quite possible that such experiences are really the same thing as lucid dreams and that the dreamer is misinterpreting the experience in “real space” terms; yet in a nonlocal universe that distinction shouldn’t affect whether such altered states (and others like hypnagogia) give access to real information about distant places or events yet to come. Probably a future theory of nonlocal noetic physics would need to abandon spacial metaphors like “plane” altogether, because space and time have no meaning in such a realm or dimension. (Even “dimension” is problematic because it implies extension and measure, like the other dimensions we are familiar with.)

The latter phenomena are to my knowledge less well documented scientifically (except in the controversial near-death-experience literature), but they are equally well-assented by thousands of years of anecdotal accounts by yogis, shamans, and ordinary “gifted” individuals. The Theosophic tradition refers to travel in the Astral Plane, although it is quite possible that such experiences are really the same thing as lucid dreams and that the dreamer is misinterpreting the experience in “real space” terms; yet in a nonlocal universe that distinction shouldn’t affect whether such altered states (and others like hypnagogia) give access to real information about distant places or events yet to come. Probably a future theory of nonlocal noetic physics would need to abandon spacial metaphors like “plane” altogether, because space and time have no meaning in such a realm or dimension. (Even “dimension” is problematic because it implies extension and measure, like the other dimensions we are familiar with.)

Nonlocal consciousness is often explained by quantum entanglement—the “spooky action at a distance” that enables bound particles to somehow share information over great distances instantaneously (much faster than light speed). It has been suggested that the brain is itself a quantum computer, and that the real action is happening at the sub-neuronal level, in microtubules within neurons that are narrow enough for quantum effects to come into play. Another (maybe compatible) explanation that I favor would be the Buddhist one: that awareness is the fundamental field or ground of being, and that physical laws rest on it, not the other way around; thus our material brains and sense organs are a kind of filter (or as philosopher Henri Bergson put it, a “reducing valve”) of consciousness, not its generator.