The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

WWKD?

All this talk of nonhumans, transhumans, post-humans. The coming Disclosure. The Singularity. We’re all focused beyond humanity to something else, some future state of being, some other species, something that transforms us and raises us to some new quantum state.

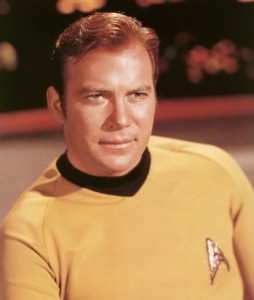

The more I think about this stuff, the more I think about Star Trek. The constant theme in that show was: What is it to be human? And the constant message was that it is our flaws, our emotions, our vulnerabilities that not only set us apart from machines and aliens, but also redeem us, that make us better than our foes.

The more I think about this stuff, the more I think about Star Trek. The constant theme in that show was: What is it to be human? And the constant message was that it is our flaws, our emotions, our vulnerabilities that not only set us apart from machines and aliens, but also redeem us, that make us better than our foes.

Captain Kirk always defeated the Others, and won in his arguments with Spock, through his humanity. He was an argument for humanity, warts and all.

I don’t think any Singularity or Disclosure or any other horizon will change our fundamental humanity. We’ll continue being the flawed and emotional beings we have always been. And crossing such a threshold that teaches us our insignificance will ultimately drive us to learn more about ourselves and love ourselves more, including all our failings and flaws and fuckups. At least I hope that’s the case.

This will be the theme of any future philosophy, any future religion: What would Kirk do?

NASA’s Low-Hanging Fruit

Bryce Zabel, coauthor of A.D.: After Disclosure, has a great reaction to today’s much-hyped NASA nerd-fest about hardy terrestrial microbes:

Today we heard about some microbes that can exist in the extremely salty, alkaline, arsenic-rich body of water in eastern California that’s known as Mono Lake. … Because Mono Lake is such an inhospitable environment for life, the scientists say, this means that maybe we can find life “in some places we might never have thought to look before.”

That’s low-hanging fruit. They could start by craning their necks up and opening their eyes. …

It isn’t just that NASA should be scolded for looking down when they should have been looking up, it’s the sense of importance they bring to their bacteria while ignoring so many other solid facts, witnesses and reports and that, by doing so, they allow the sense of derision the media heaps on anyone who dares believe that UFOs are sometimes physical craft from someplace that isn’t here.

Read Zabel’s post, Dear NASA… We like the Super-Tough Microbes, Yes, But….

NASA UFO footage

If you’re on the fence about UFOs, take a look at these collections of NASA photos and footage compiled by LunaCognita and see what you think. Most of the still photos aren’t particularly compelling, and the perfectly straight-moving objects in Earth orbit clearly appear to be satellites, space junk, or dust. But the footage of objects making turns is pretty astonishing (our objects in space can’t rapidly change direction). And some of the footage from the Apollo missions is very weird. Like the object in the first video casting a shadow as it zig-zags over the moon (at 4:13)–WTF is that?

Ignore the cheesy music, but don’t turn off your sound, as some footage contains interesting astronaut dialogue. In the second compilation, note the exchange between Dr. Edgar Mitchell and Alan Shepherd on the lunar surface (at 5:13 in): “We’ve had visitors again…”

What I’d like to know is where and how LunaCognita obtained this footage.

This Is Your Brain on UFOs

The very sound science on memory and its fallibility I discussed in the previous post is, as I argued, particularly relevant to the question of close encounters … and not, as most psychologists would hold, simply to cast doubt on their objective reality. I think that it is precisely the kind of memory research that thus far has mainly been used to discredit abductions that might also lead to some fascinating new hypotheses actually consistent with the reality of such experiences.

I suggested a while back that the range of bewildering experiences reported by contactees is surprisingly, even uncannily, consistent with the range of experiences that can be produced by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Pairs of rapidly alternating electromagnets applied to the scalp can generate weak electrical impulses in the brain that, depending on where they are applied, may produce not only sleep paralysis-type effects (paralysis and intense fear) but also distorted time, hallucinated voices that would be experienced as telepathy, light effects, a sense of religious communion, enhanced cognition or creativity, and physical sensations such as levitation.

We can’t say with any certainty what UFOs are, but there is now no doubt that some are real, that they are technological, and that they interact with humans. There is no doubt that “contact” (in some sense) occurs. As long as we accept this, we need only invoke Occam’s Razor. The most parsimonious general explanation for bewildering contact or abduction experiences is neither “they are real” nor “they are confabulated” (as Susan Clancy for example argues) but a fascinating combination of the two: They represent an interaction between a real physical encounter and some form of electromagnetic cortical stimulation that radically distorts’ contactees’ perceptions. The stimulation could be deliberately applied or it could be incidental, or both.

Were the typical abduction experience limited to bedroom visitation, then Clancy’s argument that abduction memories are just elaborated constructions based on an episode of sleep paralysis—spontaneous hiccups in sleeping/waking—would hold more weight (and I’m willing to accept that that this explanation does apply in some or even many cases—perhaps all the ones she examines in her book). By extension, if abduction experiences consisted solely of hearing voices and commands, then it would be easier to simply attribute them to paranoid schizophrenia. If they consisted solely of religious raptures and communion type experiences, we could explain them readily as temporal lobe epilepsy. Yet such experiences typically seem to involve a combination of these things, and I am not aware of any common type of disordered thinking/perception that involves all of these experiences and occurs in otherwise healthy individuals in the context of seeing or being approached by a strange aerial vehicle (sometimes verified by other witnesses).

This high overlap strongly suggests to me that many abduction cases do represent a close or intimate encounter with someone or something real, but that the experienced “reality” consists of perceptions and thoughts and images recruited from within the abductee’s brain, not what objectively occurred. TMS seems like the best explanation—and one that would hold whether UFOs were extraterrestrial or terrestrial in origin.

TMS effects could first of all (sometimes, at least) be incidental to a close encounter. All evidence points to UFOs using some sort of electrogravitic propulsion; they appear to generate powerful magnetic fields in their vicinity. Simple proximity to UFOs commonly causes electrical systems in automobiles, planes, and radios to go haywire or simply fail. The same thing might happen to the electrical systems in contactees’ brains through simple proximity to such an object. For an analogy, think of Roy Neary’s crazily haywire truck dashboard when he has his first run-in with a UFO in Close Encounters—all the spinning dials, radio turning on, etc. This is like what happens with TMS. This is your brain on UFOs.

Or TMS effects could be deliberately applied. Use of paralyzing and mind-altering technology is a common theme in close-encounter reports. As certain military encounters suggest, UFOs themselves can deliberately disable airplane or missile-launch systems, so some sort of remote targeted electromagnetic scrambling of witnesses’ brains is certainly plausible. UFO-nauts themselves are frequently described to use hand-held devices (such as the often-reported “flashlights”) to paralyze people. It certainly would make sense that something like TMS would be an effective tool to control and confuse a person without causing bodily harm or leaving a physical trace (as a drug would).

TMS technology is already widely used in psychology laboratories and is even being developed for use in by the military, so it is also certainly within the capability of secret groups in the military or intelligence utilizing the UFO mystery for its own purposes (such as those explored by Mark Pilkington in his recent book Mirage Men).

Memory is unreliable and subject to distortion even under the best of circumstances. Often two witnesses will report different colors or models of car in a hit and run, or give completely different descriptions of an assailant, and it is easy to generate false memories even without the help of magnetic fields or drugs. If something like TMS is involved, there may be little or no “there there” to contactees’ memories, and certainly nothing recoverable through hypnosis or any sort of therapeutic “regression.” It would be as unlikely as describing objectively what happened during an LSD trip or drunken bar crawl—there’s no objective sober perceiver in the brain alongside the impaired one, nothing to record the experience as it ‘really’ happened. This black-box nature of the phenomenon would open a big door to the kinds of cultural construction and post-facto sense-making using cultural archetypes that abduction’s critics like Clancy quite reasonably point to. Not to mention the forms of deception and social control Vallee warns of.

Whatever the case, the term “contactees” seems to represent a misplaced optimism on the part of those studying the phenomenon. Contact implies communication or sharing. But that hardly seems the character of most accounts. Misdirection, confusion, and exploitation seem to be the main themes. Whether achieved through TMS or something else, the remembered experiences of contactees are more likely compelling images and sensations and archetypes recruited from within their own brain, with the contactee as thus an unwitting participant in the deception. It is the opposite of communication. As long as we take the contact “image” literally and don’t do our best to peer behind the curtain (or break into the projection room, in Vallee’s metaphor), we are falling victim to that deception.

Breaking Astrobiology News…

Interesting news from NASA:

WASHINGTON — NASA will hold a news conference at 2 p.m. EST on Thursday, Dec. 2, to discuss an astrobiology finding that will impact the search for evidence of extraterrestrial life. Astrobiology is the study of the origin, evolution, distribution and future of life in the universe.

(from their press release)

AOL News has some speculation about what the finding might be.

Cool Old Documentary

A classic, cool UFO documentary from the 1970s, UFOs Are Here!, has just been made available online. It features Jacques Vallee, Kenneth Arnold, J. Allen Hynek, and others–even Steven Spielberg. Skip past the sorta cheesy new tacked-on preamble by Stan Deyo (first 10 minutes).

Un phenomenon psychologique

Late this past May I attended a symposium called “Alien Abduction Experiences: Normal Science or Revolutionary Science?” at a conference of scientific psychologists in Boston. The speakers included eminent abduction researcher Budd Hopkins and abduction ‘debunker’ Susan Clancy—two polar opposites in the whole abduction question.

As both a member of the psychology organization hosting the symposium and a believer (probably rare in that room) in UFOs—and one also open-minded to the particularly controversial question of abduction—I was excited to see what would transpire, but I also had a lot of trepidation. I knew that Hopkins would be walking into a lion’s den, as the audience consisted of the most “hard-science” side of psychology: those who do laboratory research that quite often discredits the less rigorous practices of therapists and those (like Hopkins) who use methods like hypnosis to supposedly recover memories of strange or traumatic experiences.

For an observer straddling both worlds, the scientific and the Fortean, the event indeed proved to be an enlightening and troubling experience. It crystallized for me exactly why ufology is so marginal to mainstream inquiry. It also reinforced my feeling that this marginalization is “our” fault (speaking now as a Fortean) as much as “theirs.” The non-openness to (and simple nonawareness of) new thinking goes both ways, to mutual detriment.

The first speaker, SUNY psychologist Stuart Appelle, sagely urged scientists to keep an open mind, citing Thomas Kuhn’s thoughts on normal versus revolutionary science and admonishing against a priori dismissal (not to mention ridicule) of ideas that don’t fit existing paradigms. Then Clancy took the floor and, after an assent to Appelle’s recommendation, passionately reiterated the argument in her book Abducted: How People Come to Think They Were Kidnapped by Aliens. Such experiences are, in her view, explainable as sleep paralysis episodes retroactively given a culture-specific construction (i.e., alien visitation) through therapeutic or hypnotic “reconstruction,” which produces elaborate memories that are actually false. She also presented data showing that those who report abduction experiences show more false recall in memory experiments and may be more susceptible to create false memories in real life than most people.

Clancy’s argument is essentially what I too had long believed, having been aware of the questionableness of hypnotic regression, having studied how strange experiences like sleep paralysis are interpreted in very culture-specific ways, and having suffered sleep paralysis myself. Only more recently had I become aware of the greater richness of data not accountable in Clancy’s terms and come to think that her argument could be overly reductive (I’ll argue why in a subsequent post).

Sadly, Hopkins, author of Missing Time and the pioneer in the study of abductions and abductees, had no idea what kind of audience he was addressing. After Clancy, he stood up and blithely rehearsed stories recovered from abductees in hypnosis, clearly unaware (or willfully ignoring?) that hypnotic memory recovery had been soundly discredited by precisely this audience. He supported these stories with faded slides of UFO landing sites and marks on the bodies of abduction victims. (Unfortunately, in an age of PowerPoint, his use of slide projector—which had to be procured specially for him—only added to his appearance of anachronism in this room of cutting-edge researchers.) I expected vocal argument from the audience, but instead the lions sat politely silent—and that polite silence spoke volumes. I don’t think anyone in the audience, except an exasperated Clancy herself, even bothered to seriously challenge him.

The accusation is always that scientists are blind to the evidence that doesn’t fall within their narrow paradigms. But the fact is—and this episode displayed it painfully—the opposite is just as often true. Mainstream ufology is well behind the times in its awareness and understanding of scientific research, especially research in the social and behavioral sciences. In this case, whether or not the psychological scientists in attendance had already made up their minds about abductions didn’t matter. Hopkins presented the kind of data—accounts from hypnosis—whose validity has long been discredited by very sound research. His was the paradigm that had been superseded, and the burden of proof in that context was to defend the validity of his methods. He didn’t, and he didn’t even seem aware of the need to.

In other words, Hopkins had been invited to make a case that the study of abductions is revolutionary science, but he completely failed to rise to this challenge, and thus only reinforced the stereotypes of how retrograde and unrigorous ufology is.

I hate to have to side with debunkers on this isssue, but ufologists should get with the times on the hypnosis question. Although her tone was dismissive, Clancy’s argument is grounded in a very compelling and fascinating body of research, one that ufologists should familiarize themselves with. I’m thinking particularly of the pioneering false memory research of University of California-Irvine psychologist Elizabeth Loftus. Loftus, who was seated right across the aisle from me in this symposium, is actually something of a hero of mine. She had been instrumental in discrediting the tragic 1990s therapeutic fad of “recovering” memories of childhood sexual abuse—memories that generally prove to be false. That fad still is a blot on the reputation of clinical psychology, and it highlights some persistent popular misconceptions about how memory operates.

Memory is now known to be a malleable and pliant thing. The brain doesn’t record experiences like a camcorder. It is constantly reshuffling images and impressions, distilling our experiences to the gist and discarding insignificant details. When we do “remember” an event, the memory is actually a reconstruction using a few salient details but mostly a lot of schematic filler. Memory is also very susceptible to manipulation. In the laboratory, Loftus and her students have shown how easy it is to generate false memories in subjects—from pseudomemories of trivial childhood experiences like getting lost in a mall on up to traumatic pseudomemories of abuse. Such distortions readily occur in human interactions such as therapy and hypnosis as well as in larger group contexts like cults.

Despite persisting popular belief to contrary, abundant research has shown that traumatic experiences do not lead to memories being “repressed.” People avoid thinking about experiences that are painful, but they do not have ‘amnesia’ for them that requires extraordinary tactics like a hypnotic trance (or intense therapy sessions) to uncover. It is common that an individual will lack a context for making sense of a traumatic experience when it occurs, and this lack of context may contribute to it essentially getting avoided and “forgotten”—not lost, but just not revisited until later experiences may shed some new light and lead to a spontaneous recall. This is quite often how real sexual abuse victims remember their experiences after a long duration.

Children may be upset by abuse experiences, but they likely don’t really understand what is happening to them or necessarily grasp that it is wrong at the time. It may only be decades later that, say, reading a magazine article about the subject or talking about their childhood with a sibling might remind them of a long-forgotten episode that then suddenly “makes sense” in terms of new, adult knowledge—leading them at that point to report the experience or seek therapy to deal with it. Abuse episodes that are spontaneously remembered in this way are much more likely to also be corroborated by other evidence or the testimony of other individuals, and thus be genuine. Sexual abuse memories “recovered” in therapy or hypnosis seldom are. Child sexual abuse probably ought to be taken as a model for how to evaluate memories of abduction experiences too.

Abduction researchers would counterargue my child abuse analogy by saying that the memory suppression could be a product of technology or drugs administered by the abductors and not simply the trauma of the experience. But consider: By the same logic, it would be just as likely that such deliberate technology would scramble and distort their perceptions, not only their memory, and thus render any subsequent recollection unreliable. That such perceptual (rather than memory) intervention is occurring in authentic close encounters actually seems to me a highly plausible hypothesis, one that could make the most parsimonious sense of all the data. (I’ll develop this argument also in a subsequent post.)

As Lacombe puts it in Close Encounters (and as the real-life Lacombe, Jacques Vallee, would agree), UFO encounters are “un phenomenon sociologique.” They are also un phenomenon psychologique. And ufologists have a responsibility to know the science in both cases; they need to be able to critically evaluate their own evidence. Unfortunately, the key abduction cases that ufologists continue to cite—the Betty and Barney Hill case, for example, and many others—are tainted by the hypnosis factor. That data simply can’t be accepted anymore, and for the sake of making their case to the scientific community as well as advancing the rigorous study of UFOs and abductions, ufologists need to bring their own methods and standards up to date. It shouldn’t be hard: There is plenty of data that is not tainted by the hypnosis factor: experiences not recovered in therapy or through any kind of “regression” but that are remembered spontaneously—just as in authentic child abuse cases—or experiences for which no forgetting has occurred.

It doesn’t help anyone to cling to outworn theories or bad science. We should be secure enough to trust that good science will only help the ufological case—it just needs to be brought to bear on the subject more fully, and in a more informed manner, than it has been.

The Singularity (Thoughts on Bifurcation, pt. 1)

“Who wants to live forever?” – Queen

Transhumanists plan for the coming Singularity, the threshold of transcendence of biological mortality and of flesh-enslaved consciousness—i.e., posthumanity. Ray Kurzweil for example clasps his hands together and squeals that the first person to be immortal is already alive, and that we can right now (through diet and exercise) try to “live long enough to live forever.”

To be sure, defeating death, escaping the infirmities of the flesh, sounds wonderful. Who doesn’t want to live forever? The trouble is, the advantages conferred by technology are never available to everyone, or even most people, and certainly not everyone all at once. Kurzweil et al.’s death-free posthuman future will not touch all of us at the same speed, although the vague hope is that somehow it will arrive to everyone eventually—trickle-down immortality.

Is there a realistic business model for delivering immortality to the masses?

Somehow space tourism symbolizes, to me, what the post-Singularity world will be like, and why I’m not as excited by it. I’m able to overlook the terrestrial ease and pleasures of the super-rich and not spend every waking moment dwelling on the fact that I’ll never remotely be able to afford a yacht or a castle, but somehow space tourism is in another category. It is a visible symbol of, not merely a luxury, but an actual transcendence that it is simply beyond the reach of all but a very privileged few. And somehow it galls me to my core. I have a hard time accepting that the hyper-privileged can travel into space if they want, and I’ll (probably) never be able to.

What, then, about immortality? That’s way beyond even a trip to the International Space Station.

Since the beginnings of civilization some 10,000 years ago, the rift between the haves and the have-nots has widened and widened. Is there any reason to think the Singularity or any social/technological horizon like that would reverse the trend? Somehow I don’t expect that the first cohort of the Uploaded Super Rich will be eager to share their privilege or even let us know of it. How will the rest of us react to news that Bill Gates uploaded his consciousness to a computer housed in an expensive artificial body? Will we be celebrating with him? Probably not. He’ll have to do it in secret … or retreat to his lunar estate.

The classic sci-fi dystopia is humanity enslaved by our machines. I imagine a slightly different future, in which humanity is enslaved—or not enslaved, just kept perpetually in the workaday status quo—by the Uploaded Super Rich, jealously protecting their immortality. The USRs will retreat to their space stations, finally to the asteroid belt or farther, each one a demigod, each one a Howard Hughes, each one descending into paranoia and finally a lonely machine madness, while the rest of us keep going to work and now and then upgrading to the latest iPhone.

Childhood’s End … and the End of Camping, Too

To me, the most haunting image in Richard Dolan and Bryce Zabel’s new book A.D. After Disclosure is this paragraph (p. 86):

There is … a story offered by a high-level intelligence official about a UFO briefing President Carter received in June 1977. It was unknown to the source what specifics were discussed, only that when the President was seen in his office, he was sobbing, with his head in his hands, nearly on his desk. It was clear that the President was deeply upset.

The authors of A.D. offer a very persuasive prediction for how humans will react to the knowledge of “Others” visiting or living on our planet. But while they comprehensively summarize the various other possibilities, they appear, along with almost everyone who has ever given an interpretation of the data, to basically favor the extraterrestrial hypothesis — that those Others come from space (or if not space, then somewhere else similarly exotic — other dimensions, the future, etc.). But my question in this post is this: Would revelation of extraterrestrials on earth be enough to bring a president to tears?

I think the reaction to a disclosure that, instead, the Others were actually from right here on earth — that is, that they were cryptoterrestrial (to use Mac Tonnies’ term) rather than extraterrestrial — would be far, far more unsettling to us individually and as a society than the authors consider. It would make sense of Carter’s reaction. It would also put the decades of government secrecy and disinformation in a whole new light. To my mind, it could almost justify it. (And bear with me.)

Our natural anxiety at the prospect of visitation by extraterrestrials (anxiety over their advanced technology, their uncertain motives, our newfound insignificance in the cosmos, etc.) would in an A.D. situation be tempered, as Dolan and Zabel note, by a great deal of awe. There would be so much to learn, so many ways in which our minds and our lives would be forced to grow and change, so much redefinition of our place in the universe. Awe may even ultimately triumph over anxiety. This would certainly be the case if, as many predict, Disclosure came with a reassurance that such beings are here to observe us, perhaps even help us, and basically mean no harm. For this reason, whatever the conflicted feelings they’d arouse in us, beings from other planets would probably not seem like monsters. Who wouldn’t want to meet one, touch one, talk to one? I know that it would be the greatest moment in my life to stand in front of an extraterrestrial being face to face.

Even if they turned out to be hostile, requiring a mobilization of our defenses, martial law, etc., we would react to them like foes — opponents — not as horrors. We describe Nazis as “monsters,” but they were fathomable, we met them on safely remote battlefields, they were technological and malevolent mainly in a political and human rights sense. Americans at home or in other places than Europe didn’t fear encountering them on lonely roads or when out camping; we didn’t have nightmares about them coming into our homes and kidnapping us. They were not horrifying archetypes of the collective unconscious.

But think how it would be different if it were to be revealed that the “aliens” had always been here, were from right here on earth, and shared a common ancestor with us. The reaction would be totally different, I think. Would there be any awe to counterbalance our anxieties?

As intellectually fascinating as the prospect of cryptoterrestrials is, I think standing face to face with a coldly emotionless, pale, and highly intelligent secretive dweller of our planet would scare me shitless and not make me feel anything in the way of awe. To the contrary: Every primal human terror, every nightmare, every notion of the monsters under our beds or visiting our homes at night, would be confirmed as real, not just as figments of our imaginations. (In a previous post I discuss how intrinsically repulsive or frightening cryptohominids would be, simply on the basis of their close-but-not-quite-human physical form.)

Think about it for a second. If there is a race of stealthy “people” who for millennia have visited and even abducted people — who are perhaps responsible not only for animal mutilations but for disturbingly similar human mutilation cases and even the 30,000 unexplained disappearances of humans every year, it would give new reality to the most horrifying of archetypes. How similar is the Nosferatu archetype for instance — pale, gaunt, bald, long fingers, as he appears in the window gazing in on us with animal desire — to a stereotypical “gray”? And what is the animal mutilation typically associated with UFOs but seemingly vampiric behavior? No one would ever go camping again.

Compounding the horror, revelation that the Others were cryptoterrestrial would make the world bleaker — depressingly so. For one thing, it would destroy the ET myth, which probably hovers in the back of our minds as a reassuring possibility more than most people would care to admit. What are extraterrestrials, at least in our pre-Contact archetypal pantheon, but a kind of hope for a world and a life that’s bigger? Some even see them as angels. Revelation of a cryptoterrestrial origin for UFOs would rob us of that Great Hope and make us feel very, very alone indeed — alone as Ripley at the end of the movie Alien. Alone in the sea of space, sharing our cramped planet with a smarter, colder distant relative that is not only mildly, thus more disturbingly, other, but also historically somewhat malevolent. In space, no one can hear you scream.

So I can’t help but feel that the cryptoterrestrial possibility would result in a very different post-disclosure world than the socially and intellectually engaged, technologically and maybe militarily mobilized world Dolan and Zabel envision. There would be zero desire for “contact,” except perhaps by a narrow subsection of scientists. Many or most global villagers would take to the streets and to the air and to the caves and to the water and to the Internet, pitchforks raised. There would be not only “social unrest” but probably an ultimately uncontainable worldwide frenzy to “destroy all monsters.” (Moreover, any slighter physical resemblance to particular human races — e.g., Asians? — would perhaps rekindle the kinds of racism it has taken a century, and the global village, to begin to erode. Humans would turn against humans, not just against the real Others.) If you think the “war on terror” is distressingly open-ended, imagine a “war on horror.”

Just in this century we possess weapons that could really pose a threat to a hidden species. Underground bases may seem safe, but we now have bunker-busting missiles — even nuclear tunneling machines. Some angry country — even ours, if compelled to by a terrified voting public — could certainly do a lot of harm to a secretive subterranean or underwater civilization with just a few well-placed nukes or deadly biological agents. So what we say of bears would probably be just as true of cryptoterrestrials: They are as scared of us as we are of them. Shitless, would be my guess.

Tonnies made a good case that this possibility — that the Others are a vulnerable, scared, earthbound species — makes the best, indeed most parsimonious (albeit counterintuitive) sense of the theatricality of UFOs and their pilots. All the bright lights — what is that but an attention-getter? They want us to see them but also be awed by their technology, so they dazzle us, orchestrate displays of their apparent military superiority. By their unpredictable, bizarre behavior they reinforce the idea of their literal otherworldiness. In abductions, as in the famous Betty and Barney hill case, they unveil almost comical star maps and point to them. The alien seductress who essentially “raped” Antonio Villas Boas afterwards pointed to her belly and then to the sky.

The entire UFO phenomenon could really be a big PR disinformation effort to preserve their safety. As much as we hate and fight the monumental disinformation about UFOs our government has engaged in for the last 60 years, the prospect of the genocide of a vulnerable terrestrial race would make that policy seem, in hindsight, not only sensible but necessary. I wouldn’t blame the secret-keepers so much if it were the case. And as Disclosure comes to seem more and more inevitable, such a reality would sort of justify the imperative to foster the extraterrestrial hypothesis at all costs — to the extent of not allowing any scientific investigation of the beings that could reveal a common genetic code. Such a policy of deception will have been, in this scenario, as much for the Others’ protection as for ours.

There are lots of stories about underground alien bases — in the Pacific Northwest, in the American Southwest, and in Asia — where superpowers’ militaries cooperate with an alien presence. Were it somehow indeed the case that such bases are more than bases but actually access points to deeply hidden enclaves of native beings, there would be no way for world powers to ever divulge that. They simply couldn’t. They would, like the cryptoterrestrials themselves, have to keep pointing to the skies in the desperate hope that it would never occur to us that their home was right here, perhaps right under our feet (and by extension, right under our beds).

Fortunately or unfortunately, it has occurred to more and more of us. Hopefully it’s just not the case.

Dolan and Zabel write that Disclosure is both impossible and inevitable. If the Others turn out to have lived here all along, I believe that Disclosure will never, ever be truthful. Otherwise there really could be a war, of the intraplanetary variety. Given their technological ability (if not strength in numbers), they would surely retaliate against any human threat in a huge way. They would be fighting for their lives, because they’d have no other home to flee to.