The Nightshirt Sightings, Portents, Forebodings, Suspicions

Hirshhorn floor

So E and I went to the Hirshhorn this weekend. It’s my favorite DC gallery, but I hadn’t been in a few years. For some reason, I totally fell in love with the way the pinkish green floor looked in my iPhone camera. Then I got mesmerized by the marble floor on the upper level.

I think the other museum visitors thought I was autistic, or retarded, taking pictures of the floor.

Secrecy and Truth

Call me crazy, but I think that the age of open, free publication has done something to debase or weaken the domain of thought in the West. Where are the really powerful and amazing ideas?

I want to Prague in 1990 because I was in love with the idea of samizdat, of an underground culture where ideas had power and to share them was risky. Until just a few months before I arrived, there had been something really at stake in typing out a copy of a play by Havel on your manual typewriter, sharing a mimeographed essay by Heidegger with a few friends, or translating The Lord of the Rings into Czech. That world disappeared, of course, and no one I suppose thinks that’s too much of a bad thing. But where did the world of the spirit go?

The Internet has amplified a global tendency, created a world where ideas are everywhere, free for the taking. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not an enemy of this. I’m suspicious of claims to “intellectual property” and despise the ridiculous controls that corporations would put on digital writing, music, and art simply in the interest of profit. And obviously I don’t think states should censor their citizens or invade their privacy. But the price of the freedom we now “enjoy” has been a kind of homogenization of thought, a loss of the feeling that there is much at stake in any idea. Everyone blogs or twitters their every thought and feeling, but does anyone worry that fewer and fewer of these thoughts and feelings have the power to actually shock or amaze?

In the free capitalist countries there is the loss of the vital underground streams that nourished thoughtful persons living in Totalitarianism. The bookstores are full of books on any conceivable minute topic, yet do we really learn anything? We eat mental oatmeal, because there’s no meat anymore. I don’t think people remember what it is like to be shocked and amazed by ideas.

Am I wrong? Is this a childish proposition?

When I write for an audience, it always seems cheap, stupid. My best writing was ever done “for the drawer.” Secrets, I am starting to think, are worth keeping. Or at least, silence.

Here’s a proposal: That there is some intrinsic connection between secrecy and truth. If something is really true, at least philosophically, it has to be difficult or hazardous to divulge. Its audience should be limited, tightly controlled, or it should be made so obscure that only a select few will pierce its veil.

This was understood perfectly by writers of Alchemy’s golden age—the hermeticists in Prague during the reign of Rudolf II, for example: Devastating ideas are kept secret, shared with a very few.

In Denmark, No One Can Hear You Scream (or, Is Beowulf a Forgery?)

M.J. Harper and others at the lively and interesting site Applied-Epistemology.com are more than a little suspicious that Beowulf, and with it most if not all of the texts written in Anglo-Saxon (“Old English”), are forgeries created in the 16th century. It’s a really interesting argument. The Tudor period was a time of incredible cultural flowering and it was a time when the newly conscious nations of Europe, including England, were hungry for documents establishing their ancient heritage and, thus, legitimacy. Every nation wanted its Homer. The trade in forged religious relics had died with the Reformation, but a vigorous trade in national and literary relics took its place, and it is likely that the libraries of the gentry, whence the contents of the emptied-out monasteries landed, would also have been full of fabrications — many of them created by out-of-work former monks and scribes.

The Beowulf manuscript in the British Library is the sole source for the supposed Dark-Age story that everyone reads in English Lit, and its provenance can only be dated with any surety to right around 1700, the first time it actually is mentioned as part of the Cotton Library collection. The fire-damaged manuscript however bears the signature of a well-connected 16th-century Anglo-Saxonist Laurence Lowell, and is generally assumed to have passed through his hands sometime in the mid-1500s. If Lowell didn’t actually have a hand in creating the document, he may have acquired it via his employer, Sir William Cecil, when Lowell worked in his household tutoring Cecil’s ward, the young Edward de Vere (the later-famous Earl of Oxford, who in my view is the best candidate for the real authorship of Shakespeare’s plays).

Not unconnected to certain players in the story of the Beowulf forgery (if it is that) was the Anglican Archbishop of Armagh, also known as Bishop Ussher. He knew Cotton and used his library for his own research, and he also famously dated the creation of the world to 4004 BC, providing fuel for centuries of Creationist absurdity about the young age of the world. He’s the one who said that fossils were put in the rock to test our faith. It is really in the sphere of literature and history that we ought to be “creationists.” Documents may well be younger than they seem, essentially cultural fossils placed in the rock, made new to look old. More and more, despite initial misgivings, I am excited by the possibility that Beowulf is a far younger creation than anybody ever realized.

One of the reasons I always loved Beowulf and tried to get friends to actually read it is that aspects of it feel so weirdly modern. It has such wonderful aspects of sci-fi horror, for example: a resentful outcast monster lurking outside the light of the cheerful halls, preying on people at night, part of a race of creatures who have acid for blood. There’s a battle at the bottom of a lake. How cool is that? It doesn’t exactly feel like mythology, but like a novel. And then there’s the final dark episode with the dragon, which is totally classic. It’s a really dark and cool story, full of twists and turns and beautiful imagery of a misty, ancient Northern kingdom. This is why, despite Woody Allen’s quip that you should never take a class where they make you read Beowulf, readers are often drawn to the story and keep trying to make (invariably terrible) film versions of it.

The “acid for blood” thing has always stood out in my mind as particularly anachronistic for a story supposedly written down somewhere on either side of the year 1,000 and based on older oral tradition. Consider how vividly the poet describes it (this is from Seamus Heaney’s translation):

Meanwhile the sword

began to wilt into gory icicles

to slather and thaw. It was a wonderful thing,

the way it all melted as ice melts …

its blade had melted

and the scrollwork on it burned, so scalding was the blood

of the poisonous fiend who had perished there.

Alien, anyone? I’m not a chemist, but this sounds like a description of nitric or sulfuric acid’s affect on iron. Those acids were discovered by the Arab alchemist Geber in the 8th century, though were not industrially produced and widely used in Britain until, well, the 16th century. I have a hard time imagining a Dark-Age Anglo-Saxon scop (poet) or even a 10th or 11th century scribe writing such a description. What kind of experience would someone in Britain at that time have with highly corrosive acids? I don’t think a writer necessarily needs to have seen or heard about a thing to be able to imagine it, but this is an awfully singular image that strikes me as out of place before the Renaissance. (I’d welcome hearing a dissenting view on that from someone more acquainted with the history of chemistry/industry.)

Even more anachronistic, to my mind, is the covert theme of Beowulf, which is melancholia. I’ve always felt that the Beowulf-poet was not just some bard reciting one of the favorite legends of his people, but an original creator of a poetic work about the sickness of his own soul. The monster that terrorizes the previously cheerful hall of Heorot reads like a model of clinical depression: He is an exile, condemned to lurk beyond the reach of the light spilling from the hall of men, forced to listen in bitterness to the sound of their harps, the clink of cups, and their laughter. Unable to join them because of his original guilt (he is one of the “sons of Cain”), he lives instead with his mother at the bottom of a murky, monster-filled lake.

Anyone who has suffered depression would recognize these images and identify with Grendel’s alienation from the cheerful happy people, the stocky, manly Beowulves of this world (and perhaps would even identify with the Freudian/Hitchcockian theme of unresolved bitter and dependent feelings toward a similarly alienated mother). Grendel is a brilliant portrait of the bitter self-exile of the depressed person. By contrast, Beowulf himself is nothing more than a comic-book caricature, a frat guy cum uber-hero. In describing this contrast between the noble hall of the cheerful heroes and the alienation of the monster, the Beowulf poet was describing his own painful alienation from his fellows. The poem was a poetic expression of that melancholy loneliness.

People have always experienced introverted sadness, but just as “clinical depression” is a cultural construct of our age, melancholia was a cultural construct of the Renaissance. It was in the 15th Century that this kind of socially alienated introversion began to be romanticized and explored as an aspect of genius by writers and philosophers and playwrights. To my knowledge, you don’t get sensitive, sympathetic portrayals of melancholics before this period; and while Grendel is not exactly a sympathetic portrayal, there is definitely something sad about him and his life. It is hard not to feel his pain as he runs off, sans arm, to die at home with his mother. It is this sympathetic aspect of his character that makes Grendel seem so modern, and so inviting to modern reimagining by writers like John Gardner.

There is the whole notion that J.R.R. Tolkien, entranced by the mysteries of Beowulf and its ancient idiom, wrote The Lord of the Rings to flesh out the ancient mythological world of the Anglo Saxons and, in the process, create a uniquely English myth. What if he wasn’t original? What if, in fact, that’s what the original 16th-century writer of Beowulf was himself doing? I’m reminded of the quote by Hegel: The mysteries of the Egyptians were mysteries for the Egyptians themselves. There is an occult recursion in history, if you look carefully, and Tolkien’s relation to Beowulf seems like an example of that process.

Some of the pleasure of the “Beowulf-as-forgery” idea is admittedly simply the thrill of conspiracy, an unsolved mystery. (Finding out the truth will require carbon-dating the manuscript–perhaps after Harper and his friends gain sufficient legitimacy for their theory that the British Library could be persuaded to perform the necessary tests on this British national treasure.) But I also find that it actually adds to my pleasure in the text to read it through the lens of its being a possible product of the age of Shakespeare or Milton. I actually think it adds to the genius of the work to see its mysteries as being part of an atmosphere of pastness created imaginatively by a Renaissance writer, rather than simply a more or less faithful recording of a Dark Age legend.

Muzeum Alchymie v Kutne Hore

E. and I made a day trip to Kutna Hora to visit an Alchemy Museum run by an acquaintance from my Prague days, Michal Pober. A mutual friend, Dan Kenney, had introduced us back in ’97 in a quiet teahouse on a secluded street in Old Town. It had been one of those Prague conversations: a long meandering chat about everything esoteric — alchemy, the astrological layout of Prague, the Battle of White Mountain (and how Descartes may have been involved), Frances Yates, and myriad other subjects.

I don’t think Michal recognized me when he found E and I quietly poking among the dusty displays (which include lots of equipment, retorts, ovens, and giant bellows) in his museum 12 years later. But he gave us the grand tour of the building anyway, and talked at length about his discoveries regarding alchemical and related activities that once transpired in the region during its golden age (well, silver age — it had been a center of silver mining in the Middle Ages).

We went up to a tower room with still-surviving Renaissance frescoes and now outfitted to look like an oratory, and our guide discoursed on a number of subjects, including the alchemical activities of one of the house’s former owners, the illegal metallurgy that had gone on in the basement during the Middle Ages, and the hermetic interests of Casanova, who had lived out his last years as a librarian in the North Bohemian town of Duchcov. (Although obviously a follower of Casanova’s teachings, I had overlooked the occult side of the famous lover’s interests.)

Michal also told us of his discovery of the location of the original house where John Dee and Edward Kelly stayed when they first arrived in Prague. When our guide had himself first returned to Bohemia, he said, he repeatedly found himself eating fish soup at a particular table in a pub next to Bethlehem Chapel, a beautiful church in a still-mostly-quiet square just slightly off the main tourist drag in Prague’s Old Town (just up the street from the tea room where we had met for tea 12 years ago). Only later, he said, did study of old maps reveal that his favorite seat in this pub, U Betlemske Kaple, had been just adjacent to what (the maps revealed) was the no-longer-existing house of Emperor Rudolf II’s courtier Dr. Hageck. It was here, “at Bethlem,” that Dee and Kelly stayed temporarily; a previous occupant of their room had been an “A –” who had covered the walls with alchemical symbols and a Latin inscription.

Now, curiously, Michal then asked if I knew what “A–” meant. It was an uncanny moment. I had been asked the same question about “the meaning of A–“, very significantly, in an alchemical dream almost exactly a decade ago. In that dream, I had been of the opinion, possibly mistaken, that it stood for “Androgyne”; this time, when I hesitated to answer, Michal explained: “Adept.”

At the point I had been asked about “A–” in my dreams, I had been studying hermetic philosophy quite actively, to the detriment of my “official” anthropological studies. But I had largely ignored Dee’s writings (other than the Monas Hieroglyphica), because as “angel magic” it struck me as less relevant. Now I really wish I had read A True and Faithful Relation sooner. Needless to say, I quickly obtained a copy on my return home — both Casaubon’s version and the recent abridgement by Edward Fenton.

Dee records that the “student, or A– skilfull of the holy stone” who had occupied the chamber, Simon Baccalaureus Pragensis, had written on the walls this message (in Latin):

“This art is precious, transient, delicate and rare. Our learning is a boy’s game, and the toil of women. All you sons of this art, understand that none may reap the fruits of our elixir except by the introduction of the elemental stone, and if he seeks another path he will never find the way nor attain the goal.”

Cosmic WTF

A new article in Sky & Telescope magazine reports on a recent discovery of a highly anomalous “optical transient” detected by the Hubble telescope in the constellation Bootes. The object, in the location of no known star or galaxy, appeared and brightened to the 21st magnitude over a span of about 100 days, and then disappeared over the next 100 days. It didn’t behave like any known supernova (which is what the sky survey was looking for), and spectrographic analysis doesn’t match any known type of object. Because they don’t know what the object is, the astronomers can’t even say how distant it is — only that it must be at least 130 light years away because no parallax was observed (which can be used to pinpoint nearer stars). They don’t know if it is (well, was) inside our galaxy or in another galaxy.

The original article is way too technical for me to follow. But I gather that hydrogen is missing from the object’s absorption spectrum. This, according to Robert Zubrin (Entering Space), would be one of the telltale indications of starship exhaust, which could potentially be detectable by our telescopes over very long distances. Could the “optical transient” have been a distant interstellar spacecraft (perhaps propelled by antimatter) accelerating or decelerating? (A number of other exotic suggestions have already been offered by S&T readers.)

If anyone reading this understands spectrography, please enlighten me!

Politely ignoring linguistic primitivity

M.J. Harper (The Secret History of the English Language–see previous post) has been taken to task for an apparent misunderstanding of how evolution works: A form can’t evolve from another living form, goes the dogma; rather, two related forms are said to share a common ancestor. So, for example, humans did not evolve from chimpanzees; rather, humans and chimpanzees share a recent (5 million years ago) common ancestor. Harper’s suggestion that the Germanic and Latinate languages “evolved from” Modern English (or something pretty close to it) sounds like making the faux pas that humans evolved from chimps, as if chimps haven’t been changing for the past 5 million years just like we have.

But that’s just political correctness—or, I suppose, good manners. The professional insistence on not calling one extant form a descendent of another extant form is really just a matter of politeness. It would offend fragile human sensibilities to say we evolved from chimps—I mean, just look at them!—so we say instead “from a common ancestor.” And the chimps feel better too, because yeah, they haven’t been just slacking off either; they’re nothing like those boobs of the Pliocene. When you assume evolution moves at the same pace for everyone, everyone saves face; everyone keeps up appearances that “we’ve all been evolving all this time, everyone evolves the same amount, nobody’s calling anyone ‘primitive.’”

But just because a word or a concept can be used derogatorily doesn’t mean it’s not descriptive. Let’s put aside political correctness (and, heck, manners) just a moment. Evolutionary biologists know that some species and some adaptations are more primitive than others. Evolution does not occur at a constant rate for all species, and there is no reason one living species couldn’t have branched off another living species that, for whatever reason, did not change at all in the interim. When speciation occurs due to geographical separation, for example, there is nothing in principle mandating that one branch could become radically different due to rapidly changing local selection pressures while the other branch could be relatively unchanged after a given period of time due to selection pressures that remained constant in its particular neck of the woods. Speciation is not Newtonian: It doesn’t demand an “equal and opposite reaction” on the part of both bifurcating species, esp. if geography is the reason for the split.

Cockroaches and coelacanths and sharks are called “living fossils” because they’ve stayed the same while the world around them has changed more rapidly. It’s not a sign of being old and stuffy; it’s a sign of a good adaptation, one that nature hasn’t found a way to improve upon in its particular niche. Harper is suggesting that this is what happened with English—or, English as she was spake in Neolithic Britain. Some sort of English (he argues) was spoken in the dim mists of prehistory by a group that settled throughout Europe. On the Continent, affected by different historical and demographic pressures, this ur-English bifurcated into two broad linguistic streams: German and French, which in turn evolved into various local forms. But on the island of Britain, it changed much more slowly. (I gather that place-name archaeology and genetics are starting to corroborate this idea, at least somewhat, although linguists will have nothing to do with it.)

In other words, following Harper’s line of thinking, saying German and French didn’t evolve from Modern English is trivially true only in the sense that they didn’t evolve from the English spoken in our day, but the English spoken thousands of years ago. Yet, if that ancient English was so close to Modern English to be regarded as, essentially, the same language, then why not say German and French evolved from English?

Well, I already answered this question: It’s just politeness that dictates you don’t say that. The Germans and French must be allowed to save face, here. No doubt, should Harper’s paradigm gain more acceptance, manners will dictate that we name the English spoken in pre-Roman times something else, like “proto-English” or whatever (since “Old English” is already misappropriated by the Anglo-Saxonists), and it will be called a “common ancestor” to modern English and the bitter tongues of the Continent.

The Secret History of the English Language

Reckoning the origins of words is a politically significant exercise, and etymologies, wherever and whenever they are from, are notoriously full of shit. They always reflect someone’s political vested interests or fantasies of “who was here first.” Yet somehow the old dons who gave us our etymological bible, the OED, have always remained above suspicion. These are tweedy respectable old guys who don’t go in for politics or fantasy (well, ahem, besides J.R.R.). And good god, what a huge dictionary it is, with such teeny tiny little words. It must all be true.

If a mysterious, snarky personage named M.J. Harper (about whom all is known is that he “lives in London”) has anything to say about it, the last hundred-odd years of English etymology, philology, archaeology, and history are due to be swept aside, and with it the hoary origin myth of the English language that we learned in school. The Secret History of the English Language is a bracing slap-in-the-face for anyone who sort of cherishes that myth. But despite my geeky love of English philology a la Tolkien and the summer I spent trying to learn Anglo-Saxon so I could read Beowulf in the original, I have to give it to this guy: I think he could be on to something.

At first, Harper’s “applied epistemology” sounds like the puffed-up ‘methodology’ of a manic-depressive paranoid who either never finished his PhD or, despite finishing it, works in a used bookstore, and either way has nursed a grudge against his professors for twenty or thirty years. As a science editor I get sent a lot of self-published books from the pseudo-science and pseudo-academic fringe — heck, I consider myself part of that fringe — so I know the signs of this mentality. But I don’t think Harper can be reduced to that rubric. He appears to be a smart guy, and rigorous enough in his thinking to be taken seriously, despite his flip tone. And a bit of snooping around on the internet reveals that ideas that harmonize well with his theory are emerging from archaeology (Win Scutt) and genetic studies (Oppenheimer) as well. I don’t know, but a bona fide paradigm shift might be in the offing.

Basically, Harper’s idea is this: English did not evolve out of Anglo-Saxon, as we were all taught. There’s no evidence this happened, and moreover, such an account of the origins of a major language runs counter to everything we know about language everywhere else in the world: It’s a remarkably inert thing. It doesn’t evolve quickly, and people don’t just throw an old one out to adopt a new one. History also offers no real evidence for the cherished English creation myth. There’s no evidence for the “Celtic” language originally spoken in the areas that were taken over by the Anglo Saxons, for example.

Harper’s method boils down simply to the application of Occam’s Razor: The simplest explanation is probably correct. It is far more likely that what the natives were speaking when the Normans arrived, what they were speaking when Hengest and Horsa arrived, and what they were speaking when the Romans arrived, and what they were probably speaking even back when Stonehenge was built, was pretty much what they speak now. Middle English is not an intermediate form between Modern English and Anglo-Saxon (mis-named “Old English”); it’s basically Modern English spelled differently, simply because it reflects the awkward beginnings of English as a written language. Anglo-Saxon, on the other hand, was a related but foreign language spoken by the foreign conquerors, which duped everyone into thinking it was the original form of English only because it happened to be written down before English ever was (though not very often or frequently—Harper even suggests Beowulf is a forgery, although I don’t think such a detail is necessary to his argument). Likewise, the Normans didn’t infuse English with its “Latinate” component. That was part of English all along.

Migrations and incursions and sweepings-away-of-whole-peoples are far more stimulating to the mind than glacial inertia. That’s why myths are full of such upheavals. Thus, how much more exciting to say that the word “beef” was imposed by our Norman conquerors after 1066 than to say that the word “beef” evolved from … well, “beef.” According to Occam’s Razor as, um, wielded by Harper, the Anglo-Saxons and Normans, like the Romans before them, didn’t do anything to the language. In both cases the “doing to” had been done long, long earlier, much more slowly, and in the opposite direction. Because English, he suggests, is really the mother of the tongues that have until now been thought to be its ancestors.

As I understand Harper’s parsimonious schema, something like English was originally spoken all over the continent, giving rise to German and the Scandinavian languages in the north as well as French and the Latinate languages to the south. (I’m ignoring for simplicity the Celtic languages that held fast all up the Atlantic seaboard, including Wales, Western Ireland, and Western Scotland.) So despite what you were told in school, “beef” was original and boeuf descended from it. Which has gotta hurt, if you’re French. The consolation for the French is that theirs is the mother of the Latinate tongues, including Latin (which originated as an artificial, written shorthand—the reason those inscriptions are so succinct). The fact that English only survived in its more or less original form on an Island makes a lot of sense: Events unfolding on the continent accelerated linguistic change. Islands often preserve older biological species even after their continental counterparts have gone extinct or been replaced, so why not languages?

Harper doesn’t point to much data, unfortunately; he’s more interested in uncovering gaps and anomalies and showing how people have imposed their own, convoluted stories to cover them up or obscure them. And the Occam’s Razor explanation sounds boring, at least at first: It requires no invasions, conquests, genocides, or any of the other colorful affairs of history. But for those whose academic reputations aren’t at stake, the implications of Harper’s theory would indeed be pretty amazing. How cool to think, for example, that English could be the oldest Indo-European language in Western Europe—a direct link to the mind and culture of, for example, the people who built Stonehenge?

Evolution of the Eye

Wikipedia has a terrific, thorough and readable explanation of the evolution of the eye from earlier structures (directional photodetectors found in simple, even single-celled organisms). It has nice diagrams and pictures of the intermediate forms leading to this astonishing structure. Next time you have lunch with a Creationist or “intelligent design” proponent–who love to flog the eye as defense of their case–do your homework first.

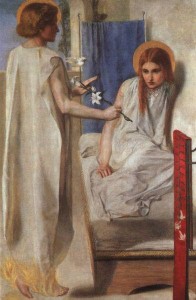

The Annunciation (pt. 2)

Alchemy was and remains the only science and art of bowing to the perception, of submitting to what can describe, in worldly terms, as “beauty,” so long as we understand that true beauty, which is formed in the eye of the beholder, is a perception of spirit in flesh, not of flesh alone. (It was never flesh alone, and anyone who thinks that it is is misguided.)

Alchemy was and remains the only science and art of bowing to the perception, of submitting to what can describe, in worldly terms, as “beauty,” so long as we understand that true beauty, which is formed in the eye of the beholder, is a perception of spirit in flesh, not of flesh alone. (It was never flesh alone, and anyone who thinks that it is is misguided.)

The Hermetic meaning of the Annunciation has to do with the same problem treated in Genesis—what you could call “the Immaculate Conception of Will.” How do you generate something from nothing? Something as simple as an action?

Spirit is the mediator, but that means nothing without understanding what is being mediated. The receptive pole, Mary, the Virgin, is the easiest to understand. Yet we should not slip so easily into the cliché that she is simply the receptive vessel. We need to understand what is meant by her purity. Like an empty, clean cup, she is fully capable of being filled by spirit. Receptivity is an abstraction as long as it is not expressed through a gesture of allowing to be filled. The ‘Mary function’ is revealed in the moment she says “Be it unto me according to thy word”—that is to say, in her gesture of willingness. The decomposition of moments in the Annunciation by the Medieval painters amounted to an analysis of this key mystery at the heart of the feminine.

Willingness must not be confused with will. Essentially, willingness is one part of will. In the analysis of will, you must confront both its male and female components.

The male component of will is a form of perception first described in Genesis I: “He saw that it was good” and repeated, by proxy, through the mouth of the Angel in Luke: “You have found favor with the Lord.” This perception that sees, and is gladdened or heartened by what it sees, is also completed, given form, by a gesture, and the Medieval painters quite aptly expressed this aspect of the larger mystery via the courtly idiom.

So, we have in this scene a chivalrous gesture expressing a perception, met in a gesture of willingness. But to understand the true quality of willingness, we must understand its viscosity, its inherent resistance. Willingness is paradoxically both avid and hesitant. You can unfold it, as it were, in time, to examine its discrete aspects: There is an initial shock or surprise, which proceeds to inquiry, then reflection, and lastly culminates in an agreement. These “moments” unfold in an instant—they are aspects of the willingness function that can only be analyzed when decomposed. The Medieval painters followed the schema of Luke’s narrative, in which Mary’s response is separated into discrete moments, but this temporal unfolding is itself a declination to our human faculties of understanding, bowing to our mind so that we, in our own sluggishness, may be pulled upward toward knowledge, toward Gnosis.

How can we not also see the temptation of Eve as wonderful, in this way? There too we have a seduction, a beguiling through promises whispered, an inquiry and reflection, and lastly a collusion, though it earned such opprobrium from the simpleminded dogmatists that Eve’s sex has always been discredited. Innocent and hesitant, but also completely receptive, the Virgin, the Mother (whether we refer to Eve, our First Mother, or to Mary, the Mother of Our Stone) shows us the Matter of divine practice: the inert earth, the substance, the first substance of Our Art.

Yet we should not get sidetracked into matters of chemistry. We were talking of will and its components. How can there arise in a universe of causes a truly original action? An Hermetic reading of Scripture gives us an answer: Will is not an exertion. It is a perception infused into an attitude, a response of the body to the divine, accepting the infusion of spirit. The act is originally empty of spirit. It arises as a natural consequence of this interpenetration of gestures; it is gestated by Nature in the womb of the Virgin. Christ, the birth, is the Act. The Act comes from God and goes back to God. Its perfection is solely a function of its exalted origins. It is Noble because it is of Noble birth. Its vicissitude is pain. Its result is the salvation of the world, the redemption of Man.

The Annunciation (pt. 1)

When I agreed to write on Hermetic philosophy for “The Nightshirt,” I never intended to discuss my accumulated knowledge of seduction, like those sites that teach shy young men “how to talk to girls.” My seduction art I teach on the other site. Yet there are numerous points of contact between Hermes’ teachings and the arts of Venus, and when I am asked about esoteric meanings contained in ancient myths I do like to remind the student of the occult not to forget that Venus concerns our Golden Art in direct as well as indirect ways.

When I agreed to write on Hermetic philosophy for “The Nightshirt,” I never intended to discuss my accumulated knowledge of seduction, like those sites that teach shy young men “how to talk to girls.” My seduction art I teach on the other site. Yet there are numerous points of contact between Hermes’ teachings and the arts of Venus, and when I am asked about esoteric meanings contained in ancient myths I do like to remind the student of the occult not to forget that Venus concerns our Golden Art in direct as well as indirect ways.

Consider for example the story of the Annunciation and Incarnation, related in the Gospel of Luke. It is full of Hermetic symbolism, providing great insight into the true philosophical meaning of Jesus as Stone. But even before we dig that deep, there’s a more mundane but equally rewarding way of reading the story, which nevertheless, in a roundabout way, carries us back to the Hermetic layer of understanding.

Luke, as you know, is the only one of the canonical gospels to include the account of the Lord’s conception. But there are other accounts, including the apocryphal Protevangelum Jacobi, which elaborate somewhat upon what happened. That version says Mary was first addressed by the angel when she went out to the well. The angel then followed her back to the temple and concluded his business there.

I am sitting right now, even as a write these words, in a well. A cafe is a well. It is a place where I might very likely contrive to run into a pretty young woman who has caught my eye, greet her, perhaps tease her. I might even scare her a little, or shock her. The next part is to take her somewhere more private and tell her lies and exaggerations, telling her things about herself that she wants to hear.

I am obviously describing a game of seduction. The aim is obvious. And a young woman—the Hebrew word transcribed as “virgin” just means young woman, a nubile teenager—she wants the very same thing the man does, only there are somewhat greater and graver restrictions on her freedom and reputation. This delicious imbalance is what creates the game called seduction. It’s what makes life interesting, for both sexes.

So I will put it to you this way. What if you were a lovely 14-year-old girl in a tiny village in the Middle East, and a handsome stranger, perhaps a merchant, some Casanova, came through town and you caught his eye, at the well, and he pursued you. He would flatter you and tell you that you were so beautiful and so innocent, that God himself had even noticed it. In order to win his way into your heart and perhaps win a pleasant hour with you under yon fig tree, he would have appealed not to your baser nature but to your highest vision of yourself, and told you not only how lovely but also how virtuous you were. If he were very, very clever, he might have persuaded you that God himself desired it that you and he should give in to your urges.

If you are a ladies man, like I am, you know perfectly well the kind of story that gets a girl’s juices flowing. When I was younger, I myself used these kinds of tricks, although perhaps without quite that much theological audacity. And God knows how ignorant girls sometimes are about the birds and the bees, especially in the country.

The brilliance of the story of Mary and her divine visitor is that no one pays attention to the angel. He seems to be just the middleman, the messenger. It’s the perfect disguise for one who wants to achieve something in secret, and it’s the classic guise of the seducer. You can read the Gospel of Luke as a children’s story about how God sent an angel to Earth, but it’s really a story about an all-too-human seduction and its aftermath.

The ancient world was full of such stories. In the Romans’ religion, God seduced lots of earth women, usually in disguise—a shower of gold, a swan, et cetera. He did it to keep his wife from finding out. But you could turn a story like that around to protect a poor Jewish girl too. You take a small town, and a clever and persuasive girl who’s desperate to save herself, and perhaps a somewhat dotty family, and a foolish husband that loves her or needs her enough to go along with a ridiculous cover story … Or who knows, maybe her husband was sick, or there was some other reason he couldn’t get her pregnant, and everybody in the village knew why. Maybe it was an open secret. There are countless such marriages.

You get my meaning.

The story of Mary and the angel Gabriel and the whole “Be it unto me according to thy word” is the sort of thing, then and now, that children believe, and you say it like you say Santa Claus is coming, and you say it with a wink, and everyone winks. It’s a face-saving lie that anyone with half a brain doesn’t literally believe but they go along with it. They go along with it, I might add, because they are basically good people, humane people, and in the end they don’t want to see her or anybody humiliated, or anybody’s life ruined. We all keep open secrets, and dissemble at times to keep a façade up. Especially in the country.

All of mythology is a soap opera, and the New Testament is no different. I’m not going to explain the whole thing to you or even pretend that it is a single coherent plot. Let’s just say that it solves a lot of a man’s problems, removes a lot of the normal inhibitions, to know He’s not actually His father’s son. Such a story wrapped around one’s origins could lead a young man from humble origins to go on and do great things.