Trauma Displaced in Time: Premonition, Synchronicity, and Enjoyment

On the morning of September 11, 2001, my alarm awoke me around 6:30AM and I did what I always try to do before dragging myself from bed: I rolled over, grabbed my notebook and pen, and jotted notes on whatever dream images I could recall from the night before. That morning I noted dreaming about driving past a pair of identical “mosques”—distinctly low, 1-story buildings, perfectly square in plan, with drab corduroy-like facades—on a street near where I grew up in Lakewood, Colorado. They were in exactly the site of an office building where, in real life (and about 30 years earlier) my father had briefly had his psychology practice, before moving his office to a nearby bank building.

I had never dreamed of “mosques” before, nor anything with Islamic overtones that I could recall. Islam was not on my radar. The only detail whose meaning I grasped at the time was the one-story-ness of the buildings (i.e., the opposite of tall buildings); my dreams have periodically featured “low buildings” as well as ruined towers that, I had figured out from a decade or more of psychoanalytic dream interpretation, mainly had a standard “castration” symbolism—stereotypical Freudian stuff, and not very remarkable. It was only in hindsight that I realized how the corduroy appearance of my dream “mosques” matched the distinctive corrugated facade of the towers that came crashing down that day.

I’m hardly the only person to have dreamed of something plausibly connected to 9/11 in the days before the event. A quick internet search turns up numerous pages of more remarkable stories of vivid dreams and visions. Bonnie McEneaney, who lost her husband in the attack, recalls in her book Messages that her husband had been gripped for months by a certainty that an attack was imminent and that he was soon to die. And 9/11 ‘prophecies’ go well beyond such narratives that are necessarily biased by hindsight (and thus fail all scientific standards of reliability). The number of ominous-seeming prophetic artworks, images, etc. unmistakeably produced prior to the 9/11 attacks but seeming to depict them is rather staggering, as a quick Internet search also reveals.

For example, issue #596 of The Adventures of Superman, released on September 12, 2001 (but obviously drawn and written sometime in the weeks immediately preceding the disaster), shows the towers smoldering after being attacked in a superhero conflict. The issue was promptly recalled by the publisher, DC Comics, making it now something of a collectors item. Even more uncanny is the bronze 1999 sculpture Tar Baby vs St. Sebastian by Michael Richards (below), in which the artist depicts himself as one of the Tuskegee Airmen, standing very erect (and building-like), being pierced by numerous planes. Could it have been inspired by a premonitory dream or vision of his own death in his studio on the 92nd floor of Tower One on 9/11?

For example, issue #596 of The Adventures of Superman, released on September 12, 2001 (but obviously drawn and written sometime in the weeks immediately preceding the disaster), shows the towers smoldering after being attacked in a superhero conflict. The issue was promptly recalled by the publisher, DC Comics, making it now something of a collectors item. Even more uncanny is the bronze 1999 sculpture Tar Baby vs St. Sebastian by Michael Richards (below), in which the artist depicts himself as one of the Tuskegee Airmen, standing very erect (and building-like), being pierced by numerous planes. Could it have been inspired by a premonitory dream or vision of his own death in his studio on the 92nd floor of Tower One on 9/11?

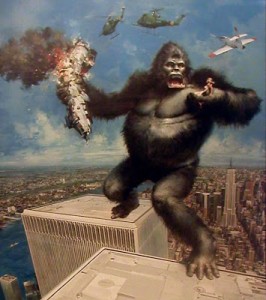

Any man who was a kid in the 1970s may also have been reminded, as the disaster unfolded that morning, of Dino DeLaurentis’s 1976 remake of King Kong, in which the giant ape scaled the then-new twin towers (instead of the Empire State Building) because they reminded him of a pair of rocks he had loved to climb back home on Skull Island. Sci-fi artist John Berkey’s publicity poster for that movie (bottom of this post), with its exploding planes, is eerie in hindsight—as are countless other images in ads, cartoons, or films showing the towers being attacked by or simply standing in ominous juxtaposition to aircraft, and these have of course fueled conspiracy theories about US government foreknowledge of (or involvement in) the attacks.

Any man who was a kid in the 1970s may also have been reminded, as the disaster unfolded that morning, of Dino DeLaurentis’s 1976 remake of King Kong, in which the giant ape scaled the then-new twin towers (instead of the Empire State Building) because they reminded him of a pair of rocks he had loved to climb back home on Skull Island. Sci-fi artist John Berkey’s publicity poster for that movie (bottom of this post), with its exploding planes, is eerie in hindsight—as are countless other images in ads, cartoons, or films showing the towers being attacked by or simply standing in ominous juxtaposition to aircraft, and these have of course fueled conspiracy theories about US government foreknowledge of (or involvement in) the attacks.

Perhaps the most amazing portent of the attacks, though—for me anyway—was Phillipe Petit’s tightrope walk between the still unfinished towers in 1974, as depicted in the documentary Man on Wire. As when the towers fell 27 years later, witnesses on the ground were shocked, awed, thrilled, and terrified, watching this French daredevil blithely balance on a cable 1,350 feet in the air that he had strung between the towers with the help of a bow-and-arrow and a couple accomplices. It is amazing to me, because it is as if the 27-year lifespan of the World Trade Center, that audacious symbol of American power and capitalism, was book-ended or framed by two highly symmetrical events: audacious aerial conquests, both pulled off with great stealth and ingenuity by foreigners who had trained extensively and in secret, for months, astonishing and frightening the crowds below who couldn’t believe their eyes.

A Night to Misremember

Skeptic Martin Gardner would probably have called any attempt to sift the “impossible” from the merely slightly improbable in the long list of “9/11 prophecies” misguided. In a book on the similarly uncanny predictions of the Titanic disaster, he writes that such problems are “not well formed”: “There is no way to estimate, even crudely, the relevant probabilities.” With the Titanic, as with 9/11, there were dreams and premonitions—or at least ones recollected after the fact. For example, in an excellent 1982 In Search Of episode, an elderly survivor, Eva Hart, who had been seven at the time, recalled that her mother had had a terrible premonition that their voyage would be fatal. Hart’s father indeed was lost with most of the other men aboard the ship, although she and her mother made it into to the lifeboats. Gardner lists other similar examples in his book.

But the most famous prophecy of the Titanic’s sinking—and Gardner’s main focus—is Morgan Robertson’s 1898 novel Futility, or The Wreck of the Titan, which appears to have foretold the disaster down to myriad “impossible” details, including not only the ship’s name (Titan), its tonnage and size, its passenger capacity, its insufficient lifeboats, the iceberg that hit it and where on the ship it struck, the exact location in the Atlantic where it sank, and even the month (April). These details seem amazing when presented in isolation, but Gardner shows that when you put them in context, some of the uncanniness dwindles. The Titanic’s name could have been pretty accurately predicted based on the names of the company’s other ships, for example. Fear of fatally hitting icebergs in the North Atlantic was a very real one at the time, and this would have been natural fodder for a writer of sea yarns. They typically occurred in spring, so April was a natural month to choose. And the idea of too-few lifeboats on a doomed ocean liner was also a pretty natural idea, and was widely used by other writers.

But the most famous prophecy of the Titanic’s sinking—and Gardner’s main focus—is Morgan Robertson’s 1898 novel Futility, or The Wreck of the Titan, which appears to have foretold the disaster down to myriad “impossible” details, including not only the ship’s name (Titan), its tonnage and size, its passenger capacity, its insufficient lifeboats, the iceberg that hit it and where on the ship it struck, the exact location in the Atlantic where it sank, and even the month (April). These details seem amazing when presented in isolation, but Gardner shows that when you put them in context, some of the uncanniness dwindles. The Titanic’s name could have been pretty accurately predicted based on the names of the company’s other ships, for example. Fear of fatally hitting icebergs in the North Atlantic was a very real one at the time, and this would have been natural fodder for a writer of sea yarns. They typically occurred in spring, so April was a natural month to choose. And the idea of too-few lifeboats on a doomed ocean liner was also a pretty natural idea, and was widely used by other writers.

In his book The Sublime Object of Ideology, Lacanian philosopher Slavoj Žižek takes this argument one step further. He notes that the disaster corresponded closely to the political-economic-cultural unconscious of the time, and for this reason took on an a weight of symbolic overdetermination that caused it to appear synchronistic in hindsight. Not only was the ship itself easy to predict in its dimensions and even its name, but some disaster or comeuppance befalling the blithe elite was also easy to anticipate. Žižek writes, “even before it actually happened, there was already a place opened, reserved for it in fantasy space. It had such a terrific impact on the ’social imaginary’ by virtue of the fact that it was expected.” In other words, if it hadn’t been the Titanic sinking, it could easily have been something else. And if Robertson’s novel hadn’t predicted it, it could have been some other novel.

Žižek is suggesting that we would not have been nearly as obsessed with “the Titanic” now or even, arguably, right afterward, had it not been for how uncomfortably closely it happened to match a zeitgeist, the mood of the ending of an era of peaceful progress and stable class distinctions that preceded it. Indeed it was this coincidence—not just with Robertson’s novel but with the whole mood of the times—that actually made it such a trauma, not the other way around, and this is why so much ink has been spilled to interpret and find meaning in it. People incessantly examined the disaster to explain how the “unthinkable” could have happened, and in the process, inevitably turned up a coincidence that looks truly uncanny in in hindsight. Žižek would say the “coincidence” is really a kind of perspective mistake: allowing the retroactive rearranging of symbolic meanings to influence how we perceive the ordinary march of causality.

When we place 9/11 in context, too, some of its coincidences seem less uncanny. The size, stature, and indeed audacity of the towers invited fantasies of audacious conquest, which could readily be expected to be expressed not only in actual real-life terror attacks but also in comic books, disaster movies, and acrobatic stunts. Indeed, terrorists had already attempted to destroy them, which surely planted the seeds of the idea in the collective unconscious as well as in the minds of those who worked in the towers.

But at a certain point—although admittedly that point is fuzzy—the parsimony of the skeptical explanations dwindles relative to the “paranormal” explanation. No amount of evidence for this will sway a hardened skeptic, but abundant evidence for precognition, premonition, and precognitive dreaming exists in parapsychology research. If we are willing to accept any of it as valid, then it means any explanation or account of 9/11 that fails to take into account how such a monumentally traumatic event may have been at least unconsciously foreseen—not by “the government” but by ordinary people, and expressed in their dreams and creative artworks—would actually be inadequate and distorted.

Synchronistic Bias?

The great dream interpreter of the 20th century was of course Freud. His legacy, psychoanalysis, is often thought of as the rule of the present by the past (or as director P.T. Anderson puts it in his Fortean film Magnolia: “We might be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us”). But that’s not completely true in Freud and even less true in some of his followers. The past is always given its meaning in the present, and so the influence of the past always changes. As events inscribe themselves in our ongoing refashioning of memory, we constantly rearrange the past and give it new symbolic shape. Memory readily selects from its infinite storehouse of associations those that match true events, and produce what can look in retrospect like “impossible” coincidences or the inexorable workings of fate. Since we tend to remember events that are significant to us, it produces what might be called a synchronistic bias to our perception.

If we are going to defend a truly synchronistic or paranormal argument for prophetic dreams, visions, and artworks, we need to confront this psychoanalytic argument: that the associative architecture of memory itself is an “acausal connecting principle,” and that what we live as open-ended in the present can in hindsight look deterministic—even uncannily so—when it is not.

An example of this could be Mark Twain’s precognitive dream about his brother Henry’s death, which Jeffrey Kripal describes in his recent book Comparing Religions

An example of this could be Mark Twain’s precognitive dream about his brother Henry’s death, which Jeffrey Kripal describes in his recent book Comparing Religions. Twain reported that in 1858 he had a dream of his brother lying in a metal casket in a suit of his own clothes and with a bouquet on his chest; a few weeks after this dream, Twain wrote, he received news that Henry had been injured in a boiler explosion aboard the steamboat they were both working on; Henry later died of an overdose of morphine given to kill his pain. In the morgue, Twain beheld the exact scene from his dream, including the clothes and the exact bouquet. It sounds uncanny, but in a series of posts on his very interesting blog, Journal of a UFO Investigator, religion scholar David Halperin does some keen Freudian literary forensics to reexamine the story, putting it back in context and bringing in some very telling clues from Twain’s fictional works about the conflicted feelings the writer held for his more upstanding, “goody-goody” brother.

Halperin deduces from evidence of intense brotherly resentment in Twain’s fiction that he would have had a lifelong unconscious death wish for Henry, and thus would probably have had many dreams, over the years, about him dying. It thus (according to Halperin’s reasoning) might not actually be too strange a coincidence for Twain, upon seeing his brother in a coffin after an unfortunate boiler accident on a Mississippi River steamboat, to recall having dreamed approximately the same thing and formed the notion that he had had a premonitory dream about it. It is significant, Halperin suggests, that Twain never wrote his dream down until 1906, giving his memory ample time—almost half a century—to sort and rearrange events into a more seamless narrative of psychic connection … and brotherly love. Halperin might have added that Twain’s retrospective interpretation at that late date would have fit well with the then-recent theories of psychical research pioneer Frederic W.H. Myers, that trauma is the energy fueling psychic phenomena like telepathy and, perhaps, premonitory dreams.

Psychoanalysis has always provided a halfway house for people who on one hand share Hamlet’s humanistic sense that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in reductive materialistic philosophy but who are nevertheless a bit afraid of the truly supernatural—or what we would now call paranormal—alternative: a universe in which things like ESP and ghosts really exist, and in which the mind can know the future or interact with matter in some mysteriously occult fashion. It’s a halfway house I myself have lived in most of my adult life. Halperin himself admits to precisely this ambivalence in another blog post on Robertson’s novelistic ‘prediction’ of the Titanic disaster: “I don’t want to believe in precognition,” he writes; “The philosophical implications are too daunting.”

But being biased against belief makes us no more clear-headed about the issues involved than wanting to believe. At what point does resolute skepticism force us to accept explanations that are actually more convoluted than what really appears to be going on, however “impossible”—that information, or emotion, is just ‘simply’ traveling backward in time from a monumentally upsetting/traumatic event? Even Twain’s dream, which is easily given a more or less mundane psychoanalytic explanation when taken in isolation, appears far more plausibly premonitory when placed alongside the countless similar examples through the history of dream recording and psychical research—mountains and mountains of cases, all fitting a fairly specific pattern of traumatic events sending shock waves through space and time via some sort of psychic ether.

We Are All Murderers

In his Freudian flight from precognition, Halperin hits on something crucial, I think, about the case of Twain’s dream, which I think applies to the dreams and prophecies of the Titanic and 9/11 too, and which also points to an interesting new way of thinking about the intersection of psychoanalysis and parapsychology and the paranormal dimensions of trauma.

He points out that, far from welcoming the reality of Henry’s accidental death on the Mississippi, Twain would have reacted with guilt. That’s the normal reaction when a person finds that dark wishes they had casually or unconsciously harbored have (impossibly) come true. This is because in our irrational, superstitious unconscious minds, we feel responsible for actually causing the calamities we’ve dimly thought of or wished for.

Žižek could have keyed in on the role played by guilt in the Titanic story too: The trauma of the Titanic was not merely the fact that everyone had been expecting some spectacular disaster to befall the rich and then were shocked when it happened; the trauma was that they had actually been wishing for such a disaster—in exactly the same way Twain may have vaguely or unconsciously wished for his brother’s death. Indeed many who saw the front page of The New York Times on April 15, 1912 must have felt on some very dim unconscious nonrational level that their wishes/desires had actually somehow caused the iceberg to sink the ship—it’s just the way the unconscious mind (which is itself like the huge dangerous submerged portion of an iceberg) works.

Žižek could have keyed in on the role played by guilt in the Titanic story too: The trauma of the Titanic was not merely the fact that everyone had been expecting some spectacular disaster to befall the rich and then were shocked when it happened; the trauma was that they had actually been wishing for such a disaster—in exactly the same way Twain may have vaguely or unconsciously wished for his brother’s death. Indeed many who saw the front page of The New York Times on April 15, 1912 must have felt on some very dim unconscious nonrational level that their wishes/desires had actually somehow caused the iceberg to sink the ship—it’s just the way the unconscious mind (which is itself like the huge dangerous submerged portion of an iceberg) works.

It is a psychoanalytic commonplace that, in our unconscious, we are all murderers. When real events accidentally fulfill our unconscious wishes—serve them up to us on a platter—people react with weird conflicting emotions they can’t fully acknowledge or process. News of the Titanic’s sinking would have produced in people not directly touched by the tragedy an unbearable and even unspeakable mix of contradictory emotions that included shock, horror, and sympathy, but also fascination and excitement, as well as a vague guilt for (unconsciously at least) having harbored murderous class resentments focused on the cosmopolitan elite they read about in The New York Times’ society pages. They would have thus “enjoyed” the news—eagerly read the story and talked about it, feeling a complex mix of weird fascination and excitement and guilt as well as horror.

What we particularly fear to see is a “body” that reminds us of our guilty enjoyment. Thus when the Titanic’s remains were finally discovered by Robert Ballard’s undersea cameras in the early 1980s, National Geographic readers gazed on the shadowy photos with a spooked fascination or even a kind of vertigo. Žižek wrote that, “By looking at the [Titanic] wreck we gain an insight into the forbidden domain, into a space that should be left unseen: visible fragments are a kind of coagulated remnant of the liquid flux of jouissance, a kind of petrified forest of enjoyment.”

What we particularly fear to see is a “body” that reminds us of our guilty enjoyment. Thus when the Titanic’s remains were finally discovered by Robert Ballard’s undersea cameras in the early 1980s, National Geographic readers gazed on the shadowy photos with a spooked fascination or even a kind of vertigo. Žižek wrote that, “By looking at the [Titanic] wreck we gain an insight into the forbidden domain, into a space that should be left unseen: visible fragments are a kind of coagulated remnant of the liquid flux of jouissance, a kind of petrified forest of enjoyment.”

9/11 reflects this same phenomenon, of course. For Americans who did not live in Manhattan or work at the Pentagon and who didn’t actually lose loved ones or friends in the attacks, the objective horror of the deaths and destruction and the feeling of national vulnerability were not the sole source of the trauma; the trauma included an added, unspeakable dimension: the contradiction between these aversive facts and our own guilty enjoyment of the cinematic spectacle, our awe at its audacity, and the incredibly warm, positive collective emotions we all shared in days following. This unspeakable enjoyment, not “the thing itself,” explains our collective obsession, re-watching the planes crashing into the towers again and again and again, dwelling endlessly on images of the towers’ wreckage in the poisonous haze, re-living and commemorating that day in our imaginations and our words.

Just as the Titanic fell conveniently into a fantasy space that history had prepared for it, 9/11 fell into a fantasy space that had been prepared for it by decades of disaster cinema and growing social antagonisms. No matter what side of the political fence you were on, it gave everyone mission and meaning—either to go and teach the Muslim world a lesson or to stand up for human rights and intercultural tolerance in a time when our country’s core values seemed in danger of evaporating. 9/11 made us all feel important, and it temporarily gave us back our national pride and unity.

Frederic Myers thought trauma was the energy underlying psychic connections between people, an argument developed by Kripal: “strong emotion (pathos), particularly around trauma and death, is the most common catalyst of robust paranormal events. Trauma, it seems, is what ‘electrifies,’ ‘zaps,’ or ‘magnetizes,’ and hence empowers the imagination. Trauma is the technology of telepathy.” I want to suggest, though, that “trauma” doesn’t quite capture what it was that may have echoed back through time, feeding people’s dreams and premonitions and artworks in the days, months, and decades prior to 9/11/2001 (or prior to April 14, 1912); it was rather the unacceptable mix of horror, guilt, giddy excitement, and awe—the way we derive enjoyment from tragedy, which cannot be consciously acknowledged—that carried that psi signal. Lacanian psychoanalysis calls it jouissance.

No Known Outside the Known

There is no equivalent word in English that captures the pleasurable-painful horror-in-bliss (or blissful horror) of jouissance—it is usually translated simply as enjoyment—but it is one of the core concepts in Lacanian psychoanalysis. Symptoms had been understood by Freud to be a way of “working through” or exorcising the pain of traumatic events or thoughts via repetition, but Lacan reversed this conception: Symptoms are actually the way we reorganize our life in order to continue to derive a secret enjoyment from something that consciously causes us suffering, pain, or revulsion. Symptoms are repetitious, ritualistic acts that attempt to manage this contradiction. The warp of our imaginary-symbolic spacetime produced by this contradiction, and our inability to be rid of our jouissance, something that is always “glued to our heel” (as Lacan put it), is what causes the strange tail-chasing, repetitive “orbiting” behavior of all neurotic symptoms. Could it also account for the spacetime distortions seen in precognitive and premonitory phenomena?

Jouissance, the secret painful enjoyment at the dark heart of our symptoms, is the “only substance acknowledged by psychoanalysis,” according to Žižek. Because it exists beyond symbolism and imagination, this unspeakable enjoyment belongs to the domain that Lacan called the Real—basically, the unknown and unknowable. Its unknowability accounts for the way we have trouble localizing it, either in ourselves (where we don’t quite want it) or in others who are presumed to have stolen it from us (the basic fantasy at the root of racism and sexism). The farther away we imagine “our” lost enjoyment, the bigger it seems to be, almost like the “dolly zoom” special effect used in Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

Jouissance, the secret painful enjoyment at the dark heart of our symptoms, is the “only substance acknowledged by psychoanalysis,” according to Žižek. Because it exists beyond symbolism and imagination, this unspeakable enjoyment belongs to the domain that Lacan called the Real—basically, the unknown and unknowable. Its unknowability accounts for the way we have trouble localizing it, either in ourselves (where we don’t quite want it) or in others who are presumed to have stolen it from us (the basic fantasy at the root of racism and sexism). The farther away we imagine “our” lost enjoyment, the bigger it seems to be, almost like the “dolly zoom” special effect used in Hitchcock’s Vertigo.

The fact that enjoyment belongs to the radically unknown space of the Real contains potentially interesting implications for parapsychology. Because enjoyment exists suspended in a protected or bottled state of unknowability (the symptom that preserves our proximity and distance), it is like the wave function in Quantum physics: It cannot be subjected to measure and differentiation and localization. It is literally “nonlocal” in both time and space. The symptom is thus an atemporal, acausal construct that defies rational analysis because its meaning-cause—its reason for being, as explained in words—lies always somewhere off in the future.

Žižek has described at length in his books how jouissance plays a sort of acausal role in our symptoms; he has always invoked science fiction stories (and Wagner’s Parsifal—see my “Passion of Einstein” post) to illustrate how psychoanalytic symptoms are actually caused by a future event that also cures them, through a kind of “time-loop” logic. Careful to avoid any hint of paranormal thinking or the dreaded “New Age obscurantism,” he is cautious to specify that he is referring to the retroactive reordering of the symbolic universe discussed previously: the way meaning only exists in the present configuration of symbols and signifiers, which are constantly being reshuffled and transformed (in other words, the past that the present affects is simply the known past, the past as it appears in hindsight through the symbolically structured filters or overlay of our perception and memory).

But this strikes me as a defense mechanism of a briliiant materialist whose brilliance has led him—oops—to discover the insufficiency of material causation. Because consider: There is no known outside the known. Once you grant that enjoyment exists outside the known, in the domain of the Real, you cannot then specify that it has any knowable properties—such as only existing here and now and not anyplace else, or traveling in only one temporal direction. (You can’t even exactly say what emotion it corresponds to—it’s sort of all of them, and none.)

So, what if we take literally, rather than figuratively, the idea that enjoyment is radically outside of knowability and locality? Could enjoyment, particularly when it is bottled in a symptom, be a kind of nonlocal medium that not only connects people across space (telepathy) but also connects people to themselves through time?

Remember: As J.W. Dunne noted in his An Experiment With Time, precognitive or premonitory dreams aren’t about future events, they are about one’s own learning of those events. What I’m proposing builds on this assumption: It may not be traumatic events per se that reverberate through the psychic ether, but rather our own ‘jouissant’ reaction to learning of those events. It is this reaction, which we have no way of consciously understanding, that gets turned into premonitory dreams and art.

Eating From the Same Plate

Throughout his books, Žižek likens enjoyment (the one and only substance) to the identical green mush eaten by the separate diners at a chic restaurant in the movie Brazil, each of whom has their own unique picture of what their meal should be standing over identical formless lumps the plates. The idea is that enjoyment is all the same, there’s only one enjoyment, even though we all perceive it differently, within different symbolic and imaginary frames, and thus have a difficult or impossible time recognizing that our enjoyment is actually shared. The diners are all eating the same formless enjoyment … but to make the analogy fully correct, fully true to Žižek’s own argument, the diners should all actually be eating from the same plate—for if it is truly unknowable and unmeasurable, this substance of the Real cannot be divided or differentiated or portioned; their “separate plates” are really mirage reflection of a single plate of enjoyment, “one thing.”

More to the point, if the diners all eat from the same plate, that same plate could be eaten simultaneously by themselves in the past, and future. If we think of jouissance this way, like an ‘out of space and time’ singularity we are all in contact with, it could serve as precisely the “acausal connecting principle” that Jung was looking for in his somewhat muddled concept of synchronicity.

More to the point, if the diners all eat from the same plate, that same plate could be eaten simultaneously by themselves in the past, and future. If we think of jouissance this way, like an ‘out of space and time’ singularity we are all in contact with, it could serve as precisely the “acausal connecting principle” that Jung was looking for in his somewhat muddled concept of synchronicity.

A dream that amazingly comes true, or a premonitory obsession that is verified, or a creative artistic inspiration that is uncannily mirrored in a real future event are all examples of “symptoms” in miniature: Irrational behaviors or thoughts or feelings that find their meaning or “answer” only in some unsettling or traumatic future occurrence. Perhaps it is even precisely our effort to “repress” the unacceptable part of our traumas—that is, to split them and bury the half we don’t want to see (our enjoyment)—that results in acausal, atemporal phenomena like precognitive dreams and premonitions.

Freud wrote of “the return of the repressed,” although it is the concept of repression that has tarnished his reputation most among scientific psychologists: While the unconscious exists, no evidence has ever been found for repression. Supposedly ‘repressed’ memories that are ‘recovered’ in hypnosis or therapy, for instance, are often false or fabulated. Real, verifiable traumas are forgotten and remain inarticulable, hard to put into words because we lacked the necessary concepts at the time they happened, but they are not actively buried by any censoring force in the psyche. A trauma victim usually awakens to the trauma spontaneously at some point, not with the ‘aid’ of discredited methods like hypnosis. But what about the unbearable contradictory feelings that might accompany a trauma? What about the unbearable dimension of enjoyment?

Perhaps repression does exist in some sense, and we have been looking for it in the wrong place. What if our symptoms are able to sequester certain thoughts or feelings, for instance guilty feelings about enjoying something objectively horrible, in a place they really can’t be found—the past? Perhaps it is precisely our repressed jouissance that “returns” in our own past, where we can have no way of understanding its meaning. If something like that is the case, then our present symptoms may contain the “repressed” of our future.

Synchro-causality

To illustrate on a small scale how temporally displaced repressed jouissance might exert a causal influence on the past via a symptom, let’s consider another uncanny case of “death on the Mississippi.” On his always interesting blog The Secret Sun, Christopher Knowles devoted a series of posts to the synchronistic perfect storm that surrounded the life, loves, and career of Scottish singer Elizabeth Fraser (right), the lead singer of Cocteau Twins (and also one of my favorite musical artists). In the mid-1990s, Fraser entered into an obsessive, intense romance with the singer Jeff Buckley (below), who had just published a wildly critically acclaimed debut album (Grace) revealing an astonishing talent that mirrored that of his father Tim Buckley. The elder Buckley had died young of a drug overdose in 1975 without really ever getting to know his son, and it was hearing Fraser’s haunting cover of his father’s 1970 “Song to the Siren” in 1994 that, according to Knowles, drove Buckley to seek out Fraser, at which point they became intensely involved for a couple of years.

To illustrate on a small scale how temporally displaced repressed jouissance might exert a causal influence on the past via a symptom, let’s consider another uncanny case of “death on the Mississippi.” On his always interesting blog The Secret Sun, Christopher Knowles devoted a series of posts to the synchronistic perfect storm that surrounded the life, loves, and career of Scottish singer Elizabeth Fraser (right), the lead singer of Cocteau Twins (and also one of my favorite musical artists). In the mid-1990s, Fraser entered into an obsessive, intense romance with the singer Jeff Buckley (below), who had just published a wildly critically acclaimed debut album (Grace) revealing an astonishing talent that mirrored that of his father Tim Buckley. The elder Buckley had died young of a drug overdose in 1975 without really ever getting to know his son, and it was hearing Fraser’s haunting cover of his father’s 1970 “Song to the Siren” in 1994 that, according to Knowles, drove Buckley to seek out Fraser, at which point they became intensely involved for a couple of years.

Their intense/obsessive relationship was on-again/off-again, and eventually Buckley left Fraser, becoming involved with another woman. It was around this time that he sequestered himself in a rented house in Memphis to write songs for his second album. Just as his musicians were on their way to Memphis to begin recording—literally, while they were in the air—Buckley took an impromptu swim in a tributary of the Mississippi and got caught in the undertow generated by a passing boat. His body was found a couple days later.

Their intense/obsessive relationship was on-again/off-again, and eventually Buckley left Fraser, becoming involved with another woman. It was around this time that he sequestered himself in a rented house in Memphis to write songs for his second album. Just as his musicians were on their way to Memphis to begin recording—literally, while they were in the air—Buckley took an impromptu swim in a tributary of the Mississippi and got caught in the undertow generated by a passing boat. His body was found a couple days later.

The coincidences and premonitions are too numerous to summarize (you should just read Knowles’ posts), but at their core are the fact that Fraser’s entire career seems in hindsight like a protracted achingly beautiful omen of Buckley’s death. She wrote and sang again and again about water, drowning, and sirens luring people to a watery grave (“Lorelei,” “Sea, Swallow Me,” etc.). Indeed her cover of Jeff’s father’s “Song to the Siren” (about being drawn to a siren who rejects her, and whom she then pleads to come be enfolded in her watery arms), for the supergroup This Mortal Coil’s album It’ll End in Tears, is one of her best-known performances. That was indeed a “siren song” in the sense that it summoned Jeff Buckley to her, and in hindsight was just one of many songs (you should also look at Cocteau Twins’ videos and album covers) whose imagery of water and loss seemed to foretell to the disaster to come. Fraser received news of Buckley’s death when in a studio in England recording the song “Teardrop” with the band Massive Attack for their album Mezzanine—another high point in her brilliant career, which largely faded after that point.

Again, there’s no way to measure coincidence. Is this all just a reshuffling and reordering of events in hindsight to construct a “destined” meaning to Jeff Buckley’s death? We can never disprove that, but Knowles does a good job of persuading that something more had to be going on. But if so, what? The standard archetypal, “synchromystic” explanation would be that somehow the “siren” archetype imprinted itself on history via these hapless individuals, who, as Knowles suggests, “were merely acting out roles written for them long before their grandparents were born.”

A skeptic willing to minimally accept that Buckley’s drowning was more than coincidence but that there was nothing paranormal occurring could go the halfway-house psychoanalytic route, offering that Fraser’s siren obsession infected Buckley’s unconscious mind and gave specific form (drowning) to an unconscious death wish, perhaps somehow to follow his father to an early grave. Less boldly, you could also suggest her obsession with water spilled over (so to speak) onto Buckley and simply increased his statistical likelihood (a) of taking spontaneous swims and (b) of perishing in the water. Žižek, for whom the past is constantly being reshuffled and given new meaning within the present Symbolic order, would probably say Buckley’s drowning was like a final psychoanalytic interpretation that “answered” Fraser’s symptom (i.e., her career) and effectively cured her of it. Indeed, as Knowles notes, Fraser has seemed to have lost her otherworldly muse and become, perhaps for better as well as worse, just a normal human being in its aftermath. In all these variants, the apparent synchronicity only appears as such in hindsight.

But if we grant that intense/traumatic enjoyment may operate nonlocally in a person’s life, I would propose that the most parsimonious and even realistic explanation of the coincidences surrounding Fraser and Buckley would be one that takes Žižek’s cautious symptom retrocausality and literalizes it: The death of Fraser’s eventual lover and muse, Jeff Buckley, was a trauma that reverberated backward in time along the resonating string of her creative enjoyment, becoming an inchoate idee fixe that appeared again and again and again in her music. Fraser channeled or drew from this trauma as the source and inspiration for most of her career, without having any way to recognize that it was a terrible future shock that she was feeling, seeing, or channeling.

Enjoyment as a Carrier

“Ready to sing, my sixth sense peacefully placed on my breath,

and listening, my ears know that my eyes are closed”

—Elizabeth Fraser/Massive Attack, “Group Four”

According to Knowles, Fraser claimed in the early 1990s that she had been the victim of sexual abuse as a child. This is possibly significant. Creative people are often “driven” (perhaps not the right word) by a trauma in their past, and I believe it is something of a commonplace in studies of paranormal phenomena that some early trauma (like abuse, or a death of a parent or sibling, or a difficult birth) is often found in people receptive to otherworldly or paranormal events. Also, given what we know about the psychotherapeutic zeitgeist of the 1990s and the tendency to overinterpret or embellish (and in many cases invent, though I’m not suggesting that here) abuse trauma memories, she may even have misrecognized or overemphasized the pain driving her as her past abuse trauma when the trauma was “really” something ahead in the future she had no way of knowing about or believing in. Could her outrageous creative talent have been like a short circuit between the twin traumas bookending her career?

In other words, I am not trying to explain Buckley’s death here: That was, I am proposing (for the sake of argument), “just” an accident. I am trying to explain the retroactive effect his death might have had on a woman’s creativity (and heck, maybe even his own father’s creativity all the way back in 1970 when he wrote “Song to the Siren”). Buckley’s death’s appearance of meaningfulness was the illusory result of his lover’s whole lifetime oeuvre leading up to it; but (and here’s where it becomes ‘paranormal’) that body of work was indeed motivated by, inspired by, that future death and the complex unbearable feelings it would provoke in her, which reverberated into the past, along the atemporal resonating string of her creative jouissance (her “sixth sense … placed on her breath,” as she describes it in the song “Group Four”). (On his blog, Bruce Duensing speculates that fear is a “carrier wave” for paranormal phenomena; I think carrier wave is a great metaphor, so long as we replace “fear” with jouissance.)

Here’s the thing, though: The shock of Buckley’s death would have been not only the trauma of his loss (she had already lost him effectively, as he had broken up with her), but the way his drowning revealed the “true meaning” of all her songs, the way it perfectly fit or matched the space her own art had repeatedly created for it, effectively confirming, at least on an unconscious level, that she was indeed the otherworldly powerful medium and “siren” that she had always allowed herself to be perceived as. How could her unconscious mind not have felt a terrible glee and awe (as well as guilt) for precisely what Knowles even intimates her siren powers actually might have done, which was channel or focus obscure dark magical forces that perhaps drew Buckley to his doom?

Here’s the thing, though: The shock of Buckley’s death would have been not only the trauma of his loss (she had already lost him effectively, as he had broken up with her), but the way his drowning revealed the “true meaning” of all her songs, the way it perfectly fit or matched the space her own art had repeatedly created for it, effectively confirming, at least on an unconscious level, that she was indeed the otherworldly powerful medium and “siren” that she had always allowed herself to be perceived as. How could her unconscious mind not have felt a terrible glee and awe (as well as guilt) for precisely what Knowles even intimates her siren powers actually might have done, which was channel or focus obscure dark magical forces that perhaps drew Buckley to his doom?

I’m doubtful Fraser’s witch powers actually reached out across the ocean and drew Buckley into the Mississippi, but Fraser’s unconscious mind might have believed precisely that possibility, and this would have added to the trauma, making his death “speak louder” into the past, back along that resonating string (or carrier wave) of her creativity. Her guilty enjoyment would have been her unconscious belief in the power of her own siren song. Her symptom—her music—through its repetition of themes of sirens and drowning, could have boosted the ‘gain’ of the painful guilty enjoyment-signal she was receiving from the future, amplifying the obviousness of the coincidence (and thus the traumatic shock) when she learned that Buckley died and the way he had died.

This is all (wild) speculation, obviously. But I do think the dark complexity of our reactions to traumas, ranging from minor emotional disturbances to personal tragedies to terrorist attacks, could be the key not only to premonitory dreams and like phenomena but also to understanding many apparent synchronicities. Some synchronicities could really be misrecognized precognition of our own guilty enjoyment.

Thanks again for answering some of my questions before I get to bother you with them! (In this specific case, more about *jouissance*).

I recall that, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, I communicated to a friend that I thought that, on some level, we as a nation *enjoyed* the event in some way. He disagreed, but what you articulate here is the argument I was trying to make at the time.

If I am reading you correctly, part of what you’re saying is that, according to Lacan (and Freud before him), we have problems with the fact that we sometimes enjoy things which we “shouldn’t” enjoy. Is the “trauma” the thing we ‘shouldn’t’ enjoy, or is it our horror at the recognition that we’re enjoying that thing (or both?)

I have really appreciated that you keep drawing attention to the fact that FWH Myers postulated that “trauma” provides the energy for psychic phenomenon. While I’ve probably noticed the correlations between traumatic experiences and psychic phenomenon “shows up” (for instance, in the traditional narrative of how a shaman becomes a shaman,) I don’t think I’d ever seen it spelled out that clearly, nor did I know that, historically, it had been. It has helped me bring into focus some themes that have been niggling at me (specifically, how trauma has been associated with psychic phenomenon in the fictional works of Time Powers, especially in *Declare*, *Three Days to Never*, and to some extent in the *Earthquake Weather* trilogy, as well as some of the darker hints we find about MK-Ultra-ish spy-world exploits).

One of my favorite examples of an author using the idea of ‘collective trauma sending information back through time’ is the “devilish” look of The Overlords from Arthur C. Clarke’s *Childhood’s End*. I supposed the knowledge that the our species is coming to an end is about as traumatic/narcissistically injurious as it could get. (I did a quick read of the wikipedia entry on Childhood’s End that reminded me of other stuff about the novel that is cogent to your topic, as well as a 1st edition cover illustrations by your guy Richard Powers).

Keep ’em coming!