The Vicinity of the Real (Tarkovsky’s Stalker)

The Zone in Andrei Tarkovsky’s late sci-fi masterpiece Stalker is one of my favorite places, real or imagined. It is a landscape of overgrown ruins, where spacetime itself is uncertain and only the experienced can guide you through. It is not that the guide (the “Stalker” of the title) knows the way—because the way is never the same as it was last time—but because he knows the indications, and knows how to test the reality there, to guide his companions safely.

Stalker, the film, is, recursively, a lot like the ambiguous catastrophe that created the Zone: It has destroyed and bent time itself, and caused causality to rupture.

The Zone could stand as the prototype for practically every postapocalyptic landscape in cinema or fiction. It is the dead marshes that surround Mordor, for instance, as well as Mordor itself. In Peter Jackson’s film of The Two Towers, the armored Elvish corpses lying just under the water seem to have been modeled on the marsh over which Tarkovsky’s famous tracking shot slowly inches, toward the Stalker’s sleeping hand. Just inches under the water are objects from various times, partly exposed in the mud: a metal tray, a syringe, coins, a religious icon, a gun, a spring. bathroom tile … You could miss them if you weren’t looking.

More fundamentally, the Zone is the Grail Kingdom from the Arthurian romances and Wagner’s Parsifal: a beautiful but strangely timeless and desolate place, where time itself seems to slow down in the vicinity of the traumatic yet life-giving miracle at its center. The Zone is the waste land created by the Grail King’s curse, like the “bradychronality” (region of viscous time) near a black hole, where the ordinary rules do not apply. It is the realm on the edge, on the rim of the symbolic—you can see its broken wreckage around you, you can grip tight to the twisted rebar jutting from the shattered concrete—but it is not yet the Real. It is what lies between the Real and consensus reality, a trickster landscape of danger and possibility.

More fundamentally, the Zone is the Grail Kingdom from the Arthurian romances and Wagner’s Parsifal: a beautiful but strangely timeless and desolate place, where time itself seems to slow down in the vicinity of the traumatic yet life-giving miracle at its center. The Zone is the waste land created by the Grail King’s curse, like the “bradychronality” (region of viscous time) near a black hole, where the ordinary rules do not apply. It is the realm on the edge, on the rim of the symbolic—you can see its broken wreckage around you, you can grip tight to the twisted rebar jutting from the shattered concrete—but it is not yet the Real. It is what lies between the Real and consensus reality, a trickster landscape of danger and possibility.

At the heart of the Zone is a room where, it is said, one’s deepest wish will be granted. This is why two men, a famous writer and a prominent scientist, have paid dearly to have the Stalker guide them through this landscape. But once they get there, they find just an empty, dirty room with water covering the floor—a nothing. They bicker, and fight, and hesitate to go in. The Stalker himself won’t go in. He reveals that his predecessor and mentor, the great master-stalker named “Porcupine,” went in, and came out to find himself a rich man. He hung himself after that, because he had gone in seeking to bring his dead brother back to life—his brother, whom he had led to his death in the Zone. The room knew better than Porcupine did his own heart’s true desire, and it was not pretty or noble.

At the heart of the Zone is a room where, it is said, one’s deepest wish will be granted. This is why two men, a famous writer and a prominent scientist, have paid dearly to have the Stalker guide them through this landscape. But once they get there, they find just an empty, dirty room with water covering the floor—a nothing. They bicker, and fight, and hesitate to go in. The Stalker himself won’t go in. He reveals that his predecessor and mentor, the great master-stalker named “Porcupine,” went in, and came out to find himself a rich man. He hung himself after that, because he had gone in seeking to bring his dead brother back to life—his brother, whom he had led to his death in the Zone. The room knew better than Porcupine did his own heart’s true desire, and it was not pretty or noble.

The scholar turns on his guide and accosts him, accusing him of toying with them. The scientist pulls out a small nuclear device he had smuggled in his backpack, to destroy the room and the superstition the room represents. But both men realize the pathetic absurdity of their gestures, and back down from their threats. The journey seems to teach them something about themselves. It is enough to come to the threshold and not walk through.

From Wish to Enjoyment

I have frequently dreamed and thought about the Zone, and the dripping, watery room at its heart, ever since I first saw Tarkovsky’s masterpiece about 30 years ago. It is a real place—in a very precise sense. Or rather, it is the no-man’s land on the edge of the Real, a dangerous margin between the Real and the ordinary world. And the film Stalker itself (based on the also-excellent novel Roadside Picnic by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky) is like the supplement, or a permutation, of countless other philosophical and sci-fi parables. It radiates outward in time and space in all directions. It is always present, like one of Phil Dick’s “common constituents.”

Stalker is a permutation of the Robert Scheckley’s short story, “The Store of Worlds,” for one thing. An old man in a run-down shack on the edge of town peddles a drug that will take the user to a dimension where your deepest wishes are fulfilled. The main character, Mr. Wayne, hesitates upon first visiting the old man, and leaves saying he will consider the offer. Later he resolves to go back and take it, yet he continually hesitates, continually puts it off because the mundane demands of his work and family routine make him too busy. Eventually he wakes up in the old man’s shack, in a dismal postapocalyptic “real world,” and pays the old man everything he owns—just some scraps—satisfied that indeed the drug (which he did in fact take on that first visit) did as promised: The banal tedious reality of an ordinary life was actually what he wished for.

Stalker is a permutation of the Robert Scheckley’s short story, “The Store of Worlds,” for one thing. An old man in a run-down shack on the edge of town peddles a drug that will take the user to a dimension where your deepest wishes are fulfilled. The main character, Mr. Wayne, hesitates upon first visiting the old man, and leaves saying he will consider the offer. Later he resolves to go back and take it, yet he continually hesitates, continually puts it off because the mundane demands of his work and family routine make him too busy. Eventually he wakes up in the old man’s shack, in a dismal postapocalyptic “real world,” and pays the old man everything he owns—just some scraps—satisfied that indeed the drug (which he did in fact take on that first visit) did as promised: The banal tedious reality of an ordinary life was actually what he wished for.

On the outside, or to other people, our secret enjoyment may look like trash or junk—indeed, just like that miserable, dripping, peeling room—but to us it is everything.

Stalker is also a lot like Kafka’s famous parable “Before the Law.” A “man from the country” comes before the Door of the Law and begs to gain access but is prevented, giving up all his money in bribes to the gatekeeper but to no end. The man waits and waits, and the gatekeeper finally shuts the door as he dies, telling him that all along this door was meant only for him. Even if, in death, he seems separated from his ultimate consuming goal, we may realize that his deeper more inaccessible wish (rather neurotically) has been to live his whole life in the presence of the gatekeeper, asking him questions, paying him bribes. This is what gives his life meaning, even if he has required this other fantasy screen (the door) as a way to explain it to himself.

It is sometimes said that the danger of the wish-granting room in the Zone is that your deepest wish won’t be what you want (or believe) it to be, or that you won’t be able to phrase it correctly. At the end, on their return to civilization, when we see how the Stalker of the film lives in a modest dwelling, with a crippled, mutant daughter, we understand exactly his fear: that somehow his obvious wish to cure his daughter or provide better for his family may not be his deepest. It is thus better to be ignorant of our deepest unconscious wish lest we end up like Porcupine.

It is sometimes said that the danger of the wish-granting room in the Zone is that your deepest wish won’t be what you want (or believe) it to be, or that you won’t be able to phrase it correctly. At the end, on their return to civilization, when we see how the Stalker of the film lives in a modest dwelling, with a crippled, mutant daughter, we understand exactly his fear: that somehow his obvious wish to cure his daughter or provide better for his family may not be his deepest. It is thus better to be ignorant of our deepest unconscious wish lest we end up like Porcupine.

But I believe this emphasis on wishes is wrong—indeed, that is meant to distract us from the real thing. Wish belongs to the category of desire, and thus is about our lack; but the more fundamental thing is enjoyment. Desire always beguiles us and causes us to misperceive or overlook the way we enjoy even in deprivation: In fact, we are always enjoying, always extracting a sustaining meaning from our circumstances. Enjoyment is our secret “thing,” that which makes life liveable. On the outside, or to other people, our secret enjoyment may look like trash or junk—indeed, just like that miserable, dripping, peeling room—but to us it is everything.

You might even say that this whole film, about a miserable man not going into the room that might fulfill his wishes, actually presents the contents of the room he does not go in; the structure of the film is a moebius, in that respect. The reality is, the Stalker is already living in and with his deepest enjoyment: His poor home, his daughter, his wife that nags and berates him, the mysterious dog that followed him throughout the film and that we now realize is his (or that has adopted him) are all he needs. Despite his pained expression, they are what his life is really about. (That vivid pain itself, etched upon a scowling, world-weary face, seems like a typically Russian form of enjoyment-in-misery.)

You might even say that this whole film, about a miserable man not going into the room that might fulfill his wishes, actually presents the contents of the room he does not go in; the structure of the film is a moebius, in that respect. The reality is, the Stalker is already living in and with his deepest enjoyment: His poor home, his daughter, his wife that nags and berates him, the mysterious dog that followed him throughout the film and that we now realize is his (or that has adopted him) are all he needs. Despite his pained expression, they are what his life is really about. (That vivid pain itself, etched upon a scowling, world-weary face, seems like a typically Russian form of enjoyment-in-misery.)

The writer detects this all along, in fact: Outside the room, he accuses their guide: “It’s not even the money. You’re enjoying yourself here.”

The Home of Enjoyment

Our enjoyment does not concern our desire, whose object/cause is always fleeting and out of reach. Desire and the language of desire highlights and centralizes a lack, and distracts us from our enjoyment, which, though we cannot put it into words, is what we are living right now, even in our deprivation.

Every uncontrollable emotion that tips over into its opposite or otherwise verges into perilous realms—an orgasm so intense it causes pain, a joke that makes us spit coke out our nose, a religious experience or UFO sighting that causes our friends and family to be embarrassed for us, a drug addiction that ruins our life, or an affection that is so extreme we keep it hidden (like sudden affection for a pet or a child that arouses tears)—this is enjoyment. Enjoyment is what it is all about, it is the meaning of life, it is the “only substance,” and it is “why there is something and not nothing.”

Every uncontrollable emotion that tips over into its opposite or otherwise verges into perilous realms—an orgasm so intense it causes pain, a joke that makes us spit coke out our nose, a religious experience or UFO sighting that causes our friends and family to be embarrassed for us, a drug addiction that ruins our life, or an affection that is so extreme we keep it hidden (like sudden affection for a pet or a child that arouses tears)—this is enjoyment. Enjoyment is what it is all about, it is the meaning of life, it is the “only substance,” and it is “why there is something and not nothing.”

Actually, all these “different forms” of enjoyment—which you could also call by the Anglo-Saxon word bliss—are the same. It is only our attitude that determines whether enjoyment presents to us as fearsome, revolting, painful, or pleasurable. When we cling to the linear world of ego and desire, enjoyment materializes or manifests as threat. Žižek cites endless examples from horror cinema—the terrifying alien or undead “thing” that seems indestructible and threatens to destroy us is our enjoyment under its negative aspect of ego-destroyer. Suffering comes from ignorance about our enjoyment, misperceiving it from the vantage point of the ego and language.

If it were not for the fact that they claimed his life, the deeply faithful Tarkovsky would probably not be troubled by Stalker’s coincidences.

In previous posts I have discussed the prophetic enjoyment that seems to be the “carrier wave” of psi information from our own future. Even (and sometimes especially) traumatic experiences like deaths and disasters actually carry an enjoyment hidden within them, which may boil down to nothing more profound than the simple joyful realization of being alive, which death always frames for us especially vividly. I suspect that this current may have somehow been responsible for the whirlpool of prophecy and tragedy around this film. The film lies at the heart of a synchronistic (or synchromystic) storm.

Stalker Synchronicities

Stalker, the film, is, recursively, a lot like the ambiguous catastrophe that created the Zone: It has destroyed and bent time itself, and caused causality to rupture.

In the film, the Stalker is clearly radiation-sick from his time in the Zone—a third of his stubbly hair having turned white—and his daughter is a full-on mutant with telekinetic powers. Six years after the film was released, in April 1986, an explosion in Chernobyl’s fourth energy block created a 30-kilometer “zone of alienation” in Soviet Ukraine, and immediately the similarity between the film and the calamity were obvious to everyone.

In the film, the Stalker is clearly radiation-sick from his time in the Zone—a third of his stubbly hair having turned white—and his daughter is a full-on mutant with telekinetic powers. Six years after the film was released, in April 1986, an explosion in Chernobyl’s fourth energy block created a 30-kilometer “zone of alienation” in Soviet Ukraine, and immediately the similarity between the film and the calamity were obvious to everyone.

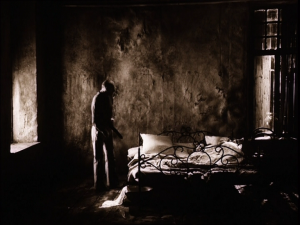

For example, while the book the movie was based on clearly explains that the Zone was created by an extraterrestrial force or visitation, the cause of the Zone in the movie is left more ambiguous, and one of the explanations mentioned is “a breakdown in the fourth bunker.” Today, in real-life, youth “stalkers” with nothing else to really live for guide people into the irradiated, mutant-haunted land around Chernobyl; a video game called S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl mashes up Tarkovsky’s spiritual sci-fi meditation with the real deadly wilderness the reactor created. And photos of Chernobyl’s abandoned buildings (e.g., below) look just like scenes out of the movie.

Eight months after the Chernobyl explosion, Tarkovski died of an unusual form of lung cancer almost certainly caused by filming Stalker in the genuinely toxic landscape surrounding an Estonian chemical plant. Although a conspiracy theory floated around that the KGB had actually “cancered” him because his films were somehow growing more anti-Soviet, this seems unlikely given that his wife (who also worked on the film) and one of the three lead actors also died of the exact same rare lung cancer.

Eight months after the Chernobyl explosion, Tarkovski died of an unusual form of lung cancer almost certainly caused by filming Stalker in the genuinely toxic landscape surrounding an Estonian chemical plant. Although a conspiracy theory floated around that the KGB had actually “cancered” him because his films were somehow growing more anti-Soviet, this seems unlikely given that his wife (who also worked on the film) and one of the three lead actors also died of the exact same rare lung cancer.

If it were not for the fact that they claimed his life, the deeply faithful Tarkovsky would probably not be troubled by these coincidences.

Tarkovsky as Hermetist

Analyzing Stalker, Žižek dismisses Tarkovsky’s “religious obscurantism,” and he shrugs and assures us that this is not what makes Tarkovsky interesting. Rather it is, he says, the “form” of his films, and the “density of time” he presents. Somehow the fact that Tarkovsky’s characters pray to the ground or actually kiss the ground means that he is more interested in matter than in the standard spiritual impulse to rise above matter. But the fact is, this sense of the spiritual manifesting in matter is nothing other than Hermeticism, which has a long and hallowed tradition in the West and took a very distinctive form in Russia; it is different from the materialism Žižek preaches.

The Cosmist school of Nikolai Fedorov and his intellectual descendents all melded a nationalist mysticism with futurist ideas for which “out there” is putting it mildly. George Young’s survey, The Russian Cosmists, is a gold mine for any aspiring sci-fi writer. On a hunt for great novel (or trilogy) ideas, they could start with the Big Idea of Fedorov himself, that our human mandate and destiny is to fulfill the Bible through technology, by bringing about the physical resurrection of all past humans. The Russian Cosmists were essentially the Eastern counterparts (or perhaps a continuation) to the Hermetic tradition, but with much more concrete visions for how future man would complete the divine work.

The Cosmist school of Nikolai Fedorov and his intellectual descendents all melded a nationalist mysticism with futurist ideas for which “out there” is putting it mildly. George Young’s survey, The Russian Cosmists, is a gold mine for any aspiring sci-fi writer. On a hunt for great novel (or trilogy) ideas, they could start with the Big Idea of Fedorov himself, that our human mandate and destiny is to fulfill the Bible through technology, by bringing about the physical resurrection of all past humans. The Russian Cosmists were essentially the Eastern counterparts (or perhaps a continuation) to the Hermetic tradition, but with much more concrete visions for how future man would complete the divine work.

I don’t know if Tarkovsky has been linked to the Cosmists and their school, but I think it’s natural that the most spiritual/religious of Soviet filmmakers gravitated to science fiction for his last, most deeply spiritual works; the spiritual and science fiction were and are a natural pairing in that country. Like some Cosmists, Tarkovsky was also a fervent believer in the paranormal, including UFOs. It all goes together. Tarkovsky made films about enjoyment, which is the substance of both the paranormal and the sacred.

From Consciousness to Enjoyment

The home of enjoyment, the Zone, the perimeter of the Real, has much in common with many spiritual concepts, from the “Imaginal” of the Sufi mystics to the spirit worlds of shamanism.

The Stalker is the ultimate Taoist, favoring weakness over strength.

The Real is not endlessly duplicated. It is endlessly the same. My Real is your Real. Through the Real—or, just across its boundaries, its tangents, its perimeter—is where causality breaks down, Time distorts, and you may find information that has no business being there. It is in this liminal edge zone that phenomena like UFOs and ESP manifest. It is a trickster realm of danger as long as we misperceive what it is really about (i.e., mistake our enjoyment for our desires or wishes, like Porcupine).

Enjoyment was what Lao Tze called “Tao,” and indeed, the Stalker is the ultimate Taoist, favoring weakness over strength, as in this strange monologue he delivers amid the ruins:

“Let everything that’s been planned come true. Let them believe. And let them have a laugh at their passions. Because what they call passion actually is not some emotional energy, but just the friction between their souls and the outside world. And most important, let them believe in themselves. Let them be helpless like children, because weakness is a great thing, and strength is nothing.”

Writing on his blog, the Hermetic scholar Aaron Cheak also describes the Stalker in Taoist terms, and beautifully expresses the crucial difference, central to this trickster’s whole message, between (temporal) desire (or “passions”) and this more ineffable and timeless counterpart or what he calls “liberating force”:

Unfortunately we are far too concerned with what we ‘want’, and put more effort into assuaging our ego’s desires than refining and deepening them to discover the liberating force that lies at their root. Our own ‘wish-fulfilling jewel’ runs deeper, operates unconsciously, and speaks a mysterious language. We must silence ourselves before we can hear it, even though its tributaries may be bubbling all around us in an abundance of synchronicities.

To silence ourselves is to open our senses to the invisible—to open our mouths and eyes to the ever-present—yet ever-occulted—symbols that live all around us. If we do this whole-heartedly, our world becomes animated like a divine icon. But if we can’t let go of our need for rational certitude at every step of the way, we risk being lead further astray that we could possibly imagine.

Enjoyment is just another word for this quintessence, which, I have argued in previous posts, is the energy in synchronicity and the modernized alchemy called psi, as well as the ’shamanic’ force liberated through even the most vanilla of Zen meditation.

I have described the Lynchian Twin Peaks-like imaginal realm that can be accessed while meditating, but the no-man’s land of Tarkovsky’s Zone would be another good analogy. In the Real’s vicinity, where concepts falter and overlap and where its pulsing heart can be glimpsed, we feel a vague trepidation and fear as well as delight. I think this Zen realm or state is much closer to the “spirit worlds” of shamanism than either tradition would want to acknowledge, because their guiding sensibilities and metaphysics are so different.

I have described the Lynchian Twin Peaks-like imaginal realm that can be accessed while meditating, but the no-man’s land of Tarkovsky’s Zone would be another good analogy. In the Real’s vicinity, where concepts falter and overlap and where its pulsing heart can be glimpsed, we feel a vague trepidation and fear as well as delight. I think this Zen realm or state is much closer to the “spirit worlds” of shamanism than either tradition would want to acknowledge, because their guiding sensibilities and metaphysics are so different.

The Stalker himself has been compared to a shaman, showing his paying clients a spiritual truth through fraud, by leading them through a landscape whose magic only he can see, to a room that, he claims, will grant their wishes, but refusing to go in himself as a way of making sure they do not either. Yet this trickery is central to his magic.

Tarkovsky himself said that “The Zone doesn’t exist. Stalker himself invented his Zone …. so that he would be able to bring there some very unhappy persons and impose on them the idea of hope. … This provocation … corresponds to an act of faith.” Yet is fiction fraud if it gives access to a genuine spiritual boon? Hope in this sense, as a sustaining source even in deprivation (or desire/lack), is none other than one of the many outward forms of enjoyment or, as Joseph Campbell might say, one of the masks of God.

Minor synchronicities abound. I read this post, went out, came back, opened Freud, and read this: “Firstly, there is no wish that seems more remote from us than this one: ‘we couldn’t even dream’ – so we believe.”

I’m trying to remember a brief comment that was disappeared from the previous post – I think it involved a couple of book titles, if you don’t mind.