Altered States of Reading (Part 2): Pynchon and the Psi Reflex

Thomas Pynchon’s sprawling unfinished 1972 novel Gravity’s Rainbow centers on an American army lieutenant, Tyrone Slothrop, whose amorous conquests around WWII London infallibly predict German V2 rocket strikes in an otherwise random distribution throughout the city. Slothrop’s weird ability puts him under the scrutiny of “Psi Section”—a division of military intelligence—who link his strange gift to Pavlovian conditioning he experienced as an infant in the laboratory of a legendary mad-genius professor, Dr. Laszlo Jamf.

One of the unwritten rules of literary fiction has always been: Thou shalt not use ESP seriously as a plot device.

Over two decades earlier, Jamf had (it is suggested) used the infant Slothrop’s erections as the “target reflex” tied to an unspecified conditioned stimulus “X.” If not reinforced, conditioned responses (like having an erection when presented with whatever X is) tend to diminish or “extinguish”—albeit often not completely. However, a theoretical possibility suggested by Pavlov in a letter to Pierre Janet is that the conditioned response could extinguish more than completely, or “beyond the zero.” The idea in the novel is that Slothrop’s adult sexual response is the result of his infant conditioning extinguishing beyond totality and into a mysterious negative “transmarginal” realm, and this is the object of much speculation in the 760-plus pages of the novel.

I call Gravity’s Rainbow “unfinished” because no one who starts the novel ever gets to the end. What starts out as fascinatingly crazy becomes boringly crazy about half the way through, and the reader’s interest, so to speak, detumesces. Revisiting the book recently, however, I confirmed what I had already suspected, which is that the secret of Slothrop’s condition(ing)—the mysterious X—remains unanswered all the way through to an increasingly ambiguous outcome, in which the character descends into madness, and even the circumstances of his childhood—including the very existence of Dr. Jamf—are called into question.

This is to be expected: One of the unwritten rules of literary fiction has always been: Thou shalt not use ESP seriously as a plot device. Writers breaking this rule quickly get relegated to the ghetto of SF, which up through Phil Dick’s day remained very much a “trash stratum.” The genre gods exist to serve the dominant mechanistic paradigm. Pynchon scrupulously avoided Dick’s fate by keeping the real nature of Tyrone Slothrop’s “gift” ambiguous, and surrounding that character with materialists (e.g., Dr. Pointsman) bent on explaining it away rationally.

Yet Pynchon clearly had a genuine fascination with parapsychology—he also wove PK experiments into his previous, much shorter novel, The Crying of Lot 49—so his ambivalence produced a kind of literary neurosis: Without descending into tepid realism, the only acceptable literary alternative is to postpone the answer, and keep postponing, in an endless spiral. The result is the kind of wordy symptom always produced by inability to be rid of a fascinating-yet-repellant remnant of the Real: A profusion of words and ideas that circle endlessly the void at its heart. (This unwillingness to accept or acknowledge the paranormal implications of the Real also accounts, I believe, for Slavoj Žižek’s descent into frenetic wordy repetition over the course of his career, but that’s another story.)

Yet Pynchon clearly had a genuine fascination with parapsychology—he also wove PK experiments into his previous, much shorter novel, The Crying of Lot 49—so his ambivalence produced a kind of literary neurosis: Without descending into tepid realism, the only acceptable literary alternative is to postpone the answer, and keep postponing, in an endless spiral. The result is the kind of wordy symptom always produced by inability to be rid of a fascinating-yet-repellant remnant of the Real: A profusion of words and ideas that circle endlessly the void at its heart. (This unwillingness to accept or acknowledge the paranormal implications of the Real also accounts, I believe, for Slavoj Žižek’s descent into frenetic wordy repetition over the course of his career, but that’s another story.)

Yet neuroses can create a secure terrarium environment in which prophetic jouissance can sprout and even bear very interesting fruit; somehow Pynchon managed to quite uncannily precognize (or at least, anticipate) some of the most interesting modern developments in a theory of psi, which partly emerged from research conducted in the 1970s in California at Stanford Research Institute (SRI).

Standing at Attention

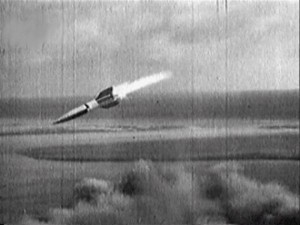

For example, at SRI and in his time on the Star Gate program, physicist Edwin May noticed that when remote-viewing targets somehow involved high-energy discharges like nuclear tests, electromagnetic pulses, or rocket launches, the viewers were almost always dead on—much more accurate than with other targets. As a result, May has theorized that psi either orients toward, or is actually carried by, signals of extreme entropy change, things moving rapidly from a state of order to a state of disorder. May has also argued that, even when it seems to take other forms, psi is always basically precognition.

The behaviors that become associated with presentiment in adulthood may be culturally conditioned reflexes associated specifically with the repression of our psi functioning during the first few years of life.

The idea that psi is linked to entropy gradients could, May suggests, find some theoretical rationale in classical physics, where time itself is often understood as tantamount to the inexorable increase in entropy dictated by the second law of thermodynamics. Interestingly, in The Crying of Lot 49, Pynchon had already homed in on the key entropy-vs.-information aspect of psi with his “Nefastis Machine,” a perpetual motion device whereby “sensitives” raise the internal temperature of a box and move a piston inside by focusing their attention on a picture of physicist James Clerk Maxwell affixed to its side. But the linkage of Slothrop’s premonitory organ to V2 strikes—which, because the rockets are supersonic, actually precede any audible warning—is a purer (and really, genius) expression of this linkage.

May clearly has hit on something important about psi. I’ve noticed that my most uncanny precognitive dreams and other premonitory experiences usually involve an entropy gradient of some sort, such as deaths, landslides, rocket launches and mishaps, explosions and fires, and breakages of household items. My life isn’t actually very exciting, fortunately, so more often than not I seem to be keying in on news reports of these events, or their signs and traces, not the events themselves (except for the breakages). This leads me to think that our unconscious preferentially attends to information about entropy gradients, whatever sensory channel we get it from, because it is relevant to our survival, and thus is part of a primitive threat-vigilance orientation.

In other words, I doubt the actual psi signal is somehow carried from the future via entropy or changes in entropy; in terms of May’s “multiphasic theory,” this would mean entropy gradients belong to what he calls the neuroscience domain, not the physics domain. (I discuss this question in the current issue of EdgeScience magazine as it applies to 9/11.) Recent advances in quantum computing provide a plausible (albeit still hypothetical) mechanism for how the brain could exchange information with itself through time, which I will discuss in a future post.

Pynchon was also prescient in linking psi to the most unconsciously willed of reflexes, the sexual response. Another big advance in parapsychology in recent years is the “first sight” theory of James Carpenter, a clinician and researcher at the Rhine Center in North Carolina, who assigns psi to the unconscious/preconscious realm as part of our basic adaptive mechanisms. Carpenter describes psi as the “leading edge” in our perception, and underscores how it operates in tandem with PK as really the root and basis of our engagement with the world. Carpenter doesn’t link it to sex per se, but his theory makes good sense of why psi seems to manifest itself most clearly in rewarding flow states and skilled engagement, a kind of enjoyment for which Slothrop’s compulsive amorous activity is a perfect metaphor.

As argued in the previous post, it may not be accidental that the most prophetic writers have also been the most frenetic, churning out creative material at a rapid pace in order to bring in a meager income—which suggests that they (a) love it and (b) don’t have any better job prospects and (c) cannot be thinking too much about what they are doing. (An extreme form of this principle is automatic writing—or in our day, automatic typing—which is an exercise that can produce very interesting unconscious and precognitive material.) Again, this would link precognition specifically to the reward system of the mesolimbic areas of the brain, and to the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is released in these areas precisely to entrain our attention and activity on “the next thing,” whether threatening or rewarding.

As argued in the previous post, it may not be accidental that the most prophetic writers have also been the most frenetic, churning out creative material at a rapid pace in order to bring in a meager income—which suggests that they (a) love it and (b) don’t have any better job prospects and (c) cannot be thinking too much about what they are doing. (An extreme form of this principle is automatic writing—or in our day, automatic typing—which is an exercise that can produce very interesting unconscious and precognitive material.) Again, this would link precognition specifically to the reward system of the mesolimbic areas of the brain, and to the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is released in these areas precisely to entrain our attention and activity on “the next thing,” whether threatening or rewarding.

Dopaminergic circuits are also involved in Pavlovian conditioning—the substitution of new behaviors and stimuli for more basic rewarding or aversive behaviors. As may have been the case with Tyrone Slothrop, the behaviors that become associated with presentiment in adulthood may be culturally conditioned reflexes associated specifically with the repression of our psi functioning during the first few years of life, when normal socialization (parental reward) compels us to be linear and reasonable in our thinking. Psi is both driven into the unconscious and possibly also somatized, leading to the hypothesis that many “hysterical” physical symptoms such as those Freud investigated in his patients could actually be precognitive signals that lack more straightforward expression. More generally, such signals could take the form of the completely nonverbal and non-verbalizable behavioral complexes that psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas called the “unthought known.”

Feed Your Psi Dolphin

Thus we shouldn’t associate “prophecy” solely with intellectual work and creative achievements like books or art or dreams; and it also isn’t remarkable or rare. Paranormal foreknowledge manifests unconsciously, unintendedly, and constantly in our lives, but often in ways we don’t want or intend, and almost always it gets lost in the chaos and noise. We are most in tune with it, though, whenever we are engaged in whatever skilled activity we are best at and most enjoy—whatever puts us in that Zen flow state that shuts down the critical mind. In Slothrop’s case, that is sexual seduction, but skilled physical activities of all kinds may be a fertile ground to look for psi. Esalen founder Michael Murphy wrote of transcendental and psychic experience in sports (including golf), and my guess is that it is in sports and martial arts that the most consistent and constant psi manifestations probably occur, yet we are not likely to become aware of them because these activities do not usually leave a paper trail. Athletes and fighters are generally not served by reflecting analytically or intellectually about what they are doing, the way writers are.

Precognition may not be seeing the future or knowing the future or even feeling the future, but instead producing a behavior that is tied to a forthcoming reward.

Acting, singing, playing a musical instrument, and other kinds of performances, when likewise engaged in with skill and complete immersion, are probably similarly conducive to psi. In the ancient world, prophecy manifested in song, for example, and this could help explain much of the psychic aspect of modern spiritualism and shamanism, as well as the overlap between genuine psi phenomena and stage magic, another highly skilled and semi-high-stakes activity that ought to take the critical left hemisphere offline temporarily. “Mixed mediumship” is the term for the oft-noted admixture of possibly real psi phenomena with stage trickery; Uri Geller, who impressed nearly all scientists who actually worked with him that his talents were genuine, nevertheless also used trickery in stage perfomances, which made it easy for pseudoskeptics like James Randi to call him a fraud.* SRI physicist Russell Targ reported to Jeffrey Kripal (Authors of the Impossible) that he received what he thought was real telepathic information while performing stage magic. It may not matter what the activity is, simply performing skilfully some behavior that consumes the left hemisphere’s attention, ideally with some physical component, seems to open the psi channel.**

There is also aviation, an occupation with notorious links to psi ability. As in athleticism or stage magic, piloting an aircraft requires senses attuned and alert, and puts the pilot in a thrilling, highly connected flow state. Flying also embodies and expresses precisely the bird’s-eye psychic view associated with threat vigilance. Examples of aviators claiming psychic phenomena are myriad—Amelia Earhart is reported to have used ESP to locate missing aircraft, for example. Some psychic aviators, fortunately, have taken up writing. One of the more naturally gifted psychics studied at SRI, for instance, was Richard Bach, pilot and author of Jonathan Livingston Seagull, who came to the attention of Targ and Hal Puthoff because that novel clearly indicated an experience with out-of-body travel, a common factor in the lives of the most gifted psychics (including Ingo Swann, Pat Price, and Joe McMoneagle).***

My point here is this: Because psi is best expressed as an unconscious reflex, it may be possible to adopt an ultra-reductive, behaviorist, even Pavlovian way of thinking about the problem, just as Pynchon does: Precognition may not be seeing the future or knowing the future or even feeling the future, but instead producing a behavior (it could be a dream, or a physical response, or an utterance, or a drawing, or a story) that is tied to a forthcoming reward. A premonition or hunch that pays off in a confirmatory action is part of a reward loop, entraining—literally, training, as in conditioning—the attentional faculty on future information. It may be that practices of skilled engagement ranging from aviation to stage magic to frenetic writing for the pulps not only open the door to psi by focusing the senses and occupying the critical, conscious mind but also simply condition the psi apparatus through providing constant rewards or payoffs that, via the magic of dopamine, propel us forward to the next reward in an ongoing chain—like feeding sardines to your psi dolphin.

My point here is this: Because psi is best expressed as an unconscious reflex, it may be possible to adopt an ultra-reductive, behaviorist, even Pavlovian way of thinking about the problem, just as Pynchon does: Precognition may not be seeing the future or knowing the future or even feeling the future, but instead producing a behavior (it could be a dream, or a physical response, or an utterance, or a drawing, or a story) that is tied to a forthcoming reward. A premonition or hunch that pays off in a confirmatory action is part of a reward loop, entraining—literally, training, as in conditioning—the attentional faculty on future information. It may be that practices of skilled engagement ranging from aviation to stage magic to frenetic writing for the pulps not only open the door to psi by focusing the senses and occupying the critical, conscious mind but also simply condition the psi apparatus through providing constant rewards or payoffs that, via the magic of dopamine, propel us forward to the next reward in an ongoing chain—like feeding sardines to your psi dolphin.

Completing the loop with a confirmation, providing those payoffs, is key. Psi needs to be seen as one half of a dual system, the other half being our everyday actions and perceptions that serve to confirm—or not—our unconscious presentimental instincts or conscious precognitive hunches. (Elsewhere I’ve suggested that psi specifically trades in probabilities coexisting in a state of superposition prior to confirmation through physical measurement—a quantum version of this idea.) The result is, I believe, a literal form of what Alfred Korzybski called time binding: reaching forward into the future and drawing ourselves toward those confirmatory nodes, those confluences where our psi is “judged” against a real state of affairs. Social time has a “cellular” structure, built around these bound symptom-loops of psi and jouissance. And creative writers, who are unknowingly copying from their own dimly intuited future works and those of other writers, are conveniently adumbrating for us, like a gravestone rubbing, this basic time-binding structure humans and all social animals, and probably even all living things (even bacteria) are engaged in.

Unfortunately, as a culture and probably as a species, we are deeply fearful of prophecy, and thus engage in elaborate mental gymnastics to disguise the living future as something else—which will be the subject of the next installment.

NOTES:

* One personality trait typical of psychics (as well as performers) is extroversion, although in some cases histrionic might better describe it: a high emotionality and attention-neediness. There may be a link between need for external validation and the emergence of psi abilities in childhood, which the trajectory of someone like Geller, or probably any number of lesser-known spiritualist mediums, shows. The extroversion of psychics (and their sometimes frustrating lack of critical thinking about what they are doing) may contribute to the overall scientific distrust of psychic displays. Scientists are mentally rigorous (and often, pretty dull) people, after all, and no matter how compelling a bit of mind reading or spoon bending might seem to a layperson, scientists are likely to be biased against most such displays because they are, quite simply, cheesy, obviously calculated to get attention.

** Given its link to spontaneous and even frenetic engagement, I would hypothesize that some of the most talented psychics—probably unknowingly—would be improv actors. Improv is a very Zen activity that rewards not thinking, just doing, and probably generates prescient scenes that may also capitalize on the group effects known to facilitate psi. Some enterprising young parapsychologist (if young parapsychologists exist) ought to systematically record improv performances and compare them to news headlines over the following two days. My hunch is this would produce extremely interesting results.

In an improv course, one is taught to follow a single overriding rule summarized as “yes, and…” (or “yes, let’s…”). To support their team members (it is thought of as a sport, not comedy) and learn to count on their support, improv performers adopt the constant attitude of total agreement with the reality already constructed on stage and contribute by adding something new that does not undo or contradict it. The result can be highly exhilarating and surprising. This habit of saying yes and honoring the world already created in an unfolding open-ended performance very much resembles the ritual of honoring psi successes I wrote about in my article on “yes-saying” in psi, and probably also can connect psi to the efficacy of “new thought” systems of positive thinking. The point is not just having a sunny positive attitude and expecting your wishes to change the world; the point is building an expectation that positive results will be honored in the future, which entrains the unconscious mind toward those outcomes. You are essentially building a habit of rewarding positive outcomes into your life, which, if you are interested in psi, coaxes unconscious psi abilities into the light of day like a shy animal.

*** Martin Caidin, a WWII bomber pilot who became a prolific writer of sci-fi techno thrillers in the 60s—including the novel Cyborg, on which the TV show The Six Million Dollar Man was based—believed himself to have psi (specifically PK) abilities and also famously wrote the novel Marooned in 1964, about a space capsule malfunction in orbit; to coincide with a movie version in 1968, he revised the plot to center on an Apollo mission requiring help from ground control and a daring rescue mission. I have not read his novel, but it is supposed to have uncannily prefigured the Apollo 13 disaster two years later. A reader sent me an article on an additional fascinating ‘synchronistic’ angle to this story: One of the NASA engineers helping solve the problem reported that a creative solution for recharging the crippled capsule’s battery came to him as a result of coincidentally seeing the film version of Marooned on the very evening he got the call about the real crisis unfolding in space.

Certainly, the critical mind must be shut down, because the critical mind is committed to consensus reality. And therefor, lots of the speculation in this article – forgive me – also ought to be shut down as irrelevant.

We have at present no physical models for these phenomena. They happen, and the less in most cases we force them the more often and vividly they occur. They are most often spontaneous, like walking and breathing. They happen because of a strong need in the person who experiences them.