Some Thoughts on the “Blackstar Working”

When Bowie’s Blackstar album came out last Friday, and the title track was finally heard in context with the other six (mostly, equally stunning) songs, there was something truly weird about it all. This was no mere album, and no mere concept album. The last two hauntingly beautiful tracks, “Dollar Days” and “I Can’t Give Everything Away” felt very much like a goodbye. The whole thing was creepy and ominous, like Bowie had something really big up his sleeve. My wife and I listened to the album three times over three days, spellbound by its depth and sadness, and could not stop talking about it. It put us in a very strange, very sad mood. And when I rose from bed Monday morning, the line “something happened on the day he died” was on repeat in my head:

Something happened on the day he died.

Spirit rose a meter and stepped aside.

And someone else took his place and bravely cried: I’m a blackstar!

Sure enough, Bowie, who spells his name on the cover using fragments of a five-pointed star, did have something big up his sleeve. When I sat down at my computer and read the awful news, I was shocked but not surprised. We now know from the producer, Tony Visconti, that he’d indeed been planning Blackstar as a deathbed gift to his fans since he learned he had incurable cancer 18 months ago, and that the songs were recorded in early 2015, when he was obviously in much better health. (There is no hint of weakness in his singing voice, although he allows his breaths to be heard on a couple tracks, which, along with every other detail, now becomes highly significant.) Has an artist … or anyone … ever gone out with such masterful control, grace, wit, and mystery? Bowie, as many remarked on Twitter, managed to stare death in the face and use it.

When the “Blackstar” video (bottom of this post) was first released in late November, there were rumors that it was somehow about or related to ISIS … which seemed a bit too narrowly geopolitical a subject matter for Bowie. Yet there was an unmistakeable whiff of the imagery that had become associated with that group’s adolescent atrocities. There was the blindfold worn by Bowie himself and then the three scarecrows at the end. There was the theme of death and, specifically, execution (“On the day of execution, only women kneeled and smiled,” etc.), in a vaguely Middle Eastern setting. And most significantly, the video opens with the retrieval of a jeweled skull from inside a spacesuit, while later we see a headless skeleton floating in orbit. Death, executions, beheadings. It seemed like Major Tom had been martyred in a particularly distressing way.

When the “Blackstar” video (bottom of this post) was first released in late November, there were rumors that it was somehow about or related to ISIS … which seemed a bit too narrowly geopolitical a subject matter for Bowie. Yet there was an unmistakeable whiff of the imagery that had become associated with that group’s adolescent atrocities. There was the blindfold worn by Bowie himself and then the three scarecrows at the end. There was the theme of death and, specifically, execution (“On the day of execution, only women kneeled and smiled,” etc.), in a vaguely Middle Eastern setting. And most significantly, the video opens with the retrieval of a jeweled skull from inside a spacesuit, while later we see a headless skeleton floating in orbit. Death, executions, beheadings. It seemed like Major Tom had been martyred in a particularly distressing way.

Knowing that this album was written and recorded a full year ago, the ISIS link makes much more sense: From the time Bowie found out he had cancer in mid 2014 until he recorded these songs, the world was transfixed by the ISIS spectacle, specifically their videos of decapitations. Bowie, unparalleled master of fame and stardom, must have recognized their savvy method: using extremity and transgression to transfix the attention of the world, capitalizing on the total whorish complicity of the media. In his own much more benevolent way, Bowie had pioneered this M.O. in his own career. Like all of us, he must have been saddened and appalled at what was happening, while at the same time reeling from his own diagnosis. His associative mind would have drawn a link between the black-clad executioners marching through Syria and Iraq and the illness spreading in his body. It now turns out that “black star” is medical jargon for a certain type of cancer lesion.

I think Bowie saw here an opportunity to commit a last heroic act: Reappropriate ISIS’s symbolic language (ritualistic executions, decapitation, blindfolds, etc.) and subvert it, utilizing his own death to draw the necessary attentional energy to a final magical intervention against the extremist violence eating away at the world. In the video, he waves a black spell book, and indeed the gorgeously designed book accompanying the LP is very like a grimoire. “BOWIE” spelled on the cover in star fragments literalizes that he is using the shattering/destruction of his self to cast a “spell” at evil, or the forces of evil. Blackstar is not about ISIS so much as a kind of magic(k)al “working” (a la Crowley) against ISIS (and what they represent). It remixes their own symbolism into a dark and beautiful summoning of female power to defeat the forces that enable that kind of base violence to flourish.

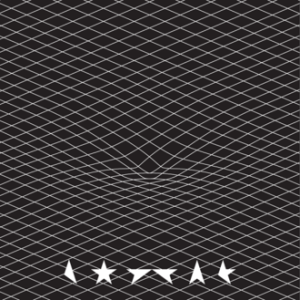

Symbolic working and re-working (or in an academic and political context, “reframing”) uses the fact that all symbols have multiple meanings. Bowie’s death two days after the album’s release provided the final bit of needed meaning to understand the “Blackstar” video: A blackstar is obviously much more than a cancer lesion; it is also a black hole, the remnant left when a very big star dies, absorbing all light (the cover of the single, right, showing a gravity well, confirms this intended meaning).

Symbolic working and re-working (or in an academic and political context, “reframing”) uses the fact that all symbols have multiple meanings. Bowie’s death two days after the album’s release provided the final bit of needed meaning to understand the “Blackstar” video: A blackstar is obviously much more than a cancer lesion; it is also a black hole, the remnant left when a very big star dies, absorbing all light (the cover of the single, right, showing a gravity well, confirms this intended meaning).

Such a heavy hole in spacetime, I think Bowie knew and hoped, could supply the necessary power for his spell against the terrestrial darkness blighting our world. What indeed did the entire world do when it found out about his brilliantly timed death, but attend ever more closely to Blackstar‘s tracks “Blackstar” and “Lazarus” and to his whole life and works? He would have counted on that black-hole-like sucking-in of all attention and meaning.

The women are the “heroes” of “Blackstar.” When the sly animal-tailed woman at the beginning of the video retrieves Major Tom’s jeweled skull and the relic is then incorporated into the circle of female power “in the Villa of Ormen” (i.e., “____ or men”), it seems to summon a spirit that punishes and destroys the initially smug blindfolded scarecrows. Bowie seems to be saying to women, and to the feminine (i.e. receptivity) in all of us: Take the power back from those stupid children. Bowie saw clearly what somehow few people want to talk about in our insane times: All violence in the world, be it ISIS, school shooters, gun nuts of all stripes, is committed by men. Terror and violence are not about religion and politics; they are about testosterone. Perpetrators are often young and confused, flooded with adolescent and young-adult male anger—precisely the raw material that older, powerful men have always summoned and channeled for wars. If women of the world stopped being impressed by male audacity—both the audacity to kill and the audacity to command death—how might that change the world?

It would thus be a mistake to read the “women kneeling and smiling on the day of execution” as women complicit and supportive of the horrors being perpetrated by their atrocious menfolk; the knowing smile on the face of the tailed woman as she appropriates Major Tom’s skull and bears it through the village toward its destination is how I take that smile—a calm “you just wait and see what’s coming” smile.

Bowie repeatedly insists that the place where the action is, the “center of it all,” is “your eyes.” Another thing a blackstar is is the pupil of the eye, which is a candidate for the materia prima in alchemy—the black raw material (i.e., what is in your field of vision) from which anything can be made. You are not a slave of ISIS, or of their media servants, or of anything or anybody doing outrageous things to capture your attention. Instead of filling your vessel-like gaze with stupidity and atrocity, look up instead, he says—look to the skies, to the stars—don’t look at all this shit being spewed on your TVs and your computer screens.

I don’t know if Bowie read Giordano Bruno, but throughout the “grimoire” accompanying the album, the lyrics to several songs are printed as stars arranged in constellations. Bowie’s “working” reminds me very much of Bruno’s 1584 attempt to reform the heavens in his book The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast: Because worldly institutions were so full of corruption and people’s values had sunk to such dismal lows in his time, Bruno felt that the constellations themselves by which humans orient their lives needed to be reformed and reshaped, their images given new meaning, and his lengthy book in dialogue form attempted precisely this. That is exactly what Bowie, that emissary from the stars, seems to be attempting in a perhaps more modest way.

The way Bowie takes and redefines “execution” is his boldest stroke. The decapitated skeleton isn’t just a martyr to ISIS; it is also someone who has followed the advice of a book that we do know Bowie had read and counted among his favorites, D.E. Harding’s Zen classic On Having No Head. Really pay attention to what you actually see in front of you, not to what you imagine or think is there. The headless skeleton floats in space in front of a pupil-like black hole, and this is precisely what the eye actually sees of the self in Harding’s vividly described satori vision: everything but a head. That’s because there is no head; only other people have such an appendage—you don’t. Recognizing this truth, in all its senselessness, is the true path to liberation.

Excellent and shared. Lots of hidden meaning in Blackstar.