Altered States of Reading (5): Kirk Allen of Barsoom

What could any Other know of the up-and-out? What Other could look at the biting acid beauty of the stars in open space? What could they tell of the great pain, which started quietly in the marrow, like an ache, and proceeded by the fatigue and nausea of each separate nerve cell, brain cell, touchpoint in the body, until life itself became a terrible aching hunger for silence and for death? – Cordwainer Smith, “Scanners Live in Vain”

Central to Harold Bloom’s theory of poetic/literary revisionism is the precarious artistic ego, which feels threatened by a brilliant predecessor. But even though the Freudian paradigm it is based on (and pretty much all of Western culture) insists that good health means maintaining intact ego boundaries, the ego is actually something many souls are capable of setting aside in experiences of higher union or cosmic consciousness. These ruptures are central in the history of religions, so why not other domains like writing (and reading)? When the ego ruptures, the negative aspects of the Real and the pain of jouissance flip or transform over into a kind of bliss and inspiration that may feel like (and may indeed be—we should remain open-minded) the channeling or downloading of information from some alien source. I described this for instance in the case of Allen Ginsberg, who experienced his ecstatic experience in college as a transmission directly from the mystical artist/poet William Blake.

The creative and the mystical or paranormal (or some indeterminate category where it is hard to tell what is really going on) is some kind of universal nexus in the domain of cultural creativity.

Jeffrey Kripal’s work (especially Mutants and Mystics) provides a good starting place for thinking about this kind of paranormal/mystical transmission in the world of literature, especially imaginative literature. Kripal uses the term “imaginal”—a word introduced by Victorian paranormal researcher Frederic Myers but made more famous by Islamist Henri Corbin—to talk about this nexus. In an a lecture that I can no longer locate on YouTube, Kripal describes a daisy chain of influence in which sci-fi and comic book writers draw on culturally-framed anomalous experiences for their art, which then shapes the anomalous experiences of their readers, which feeds back into art and re-shapes cultural framings of the paranormal, and so on—what he calls “the fantastic loop between consciousness and culture.”

I can think of no better example of such a fantastic loop than the famous case study “Kirk Allen” in Robert M. Lindner’s 1955 pop-psychiatry memoir The Fifty Minute Hour. This young man, described as a brilliant scientist working on a secret government project during the war (implicitly the Manhattan Project, which was surely a misdirection to disguise the subject’s true identity), was referred to Lindner in Baltimore because he was spending less and less time in actual reality and more and more time in an imaginary world that, it turned out, was based on an unnamed multi-volume pulp sci-fi epic popular at the time. Lindner describes how Mr. Allen, out of his obsession with this alien world and his confused belief that it was actually about him, had, after he got to the end of his “biography,” continued writing “his” story and (to do the necessary research) habitually visited this other planet in a sort of dissociative state.

The doctor was stymied at first, because there seemed to be no reason for his clearly bonkers subject to stay in the real world—there were so many fascinating rewards in that other one, where he was a heroic ruler, married to a beautiful princess, etc. Thus there was nothing to induce him to see real reality for what it was. Lindner finally hit upon a novel therapeutic strategy: By entering the subject’s fantasy himself, taking an equally obsessive interest in it and, in the process, holding an uncomfortable mirror up to his patient’s behavior, perhaps he could gradually loosen its hold over the young man.

So he did … and it worked. And in what is surely one of the most interesting instances of psychotherapeutic countertransferrence ever documented, the doctor successfully got his patient to abandon his alternate reality, seeing it as false and pointless, but in the process developed his own deepening fascination and near-obsession with the interplanetary empire where his patient had been spending so much time. In the end, Allen breaks the spell for Lindner by admitting he made the whole thing up, although it’s unclear what he really believed earlier on.

In his book The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan used this episode as a touchstone for thinking about supposed alien abductions as a kind of folie-a-deux between abductee and researcher: The abductee seduces the researcher into an alternate (and in Sagan’s mind, clearly deluded) reality or belief system, but the researcher then takes the ball and elaborates and deepens this new reality. Sagan thinks that Allen did Lindner a huge favor in the end, effectively rescuing the psychiatrist (who interestingly was an honorary fellow of the Fortean Society before his early death in 1956) from the fate of John Mack, whose reputation was damaged by credulity in a phenomenon some of his subjects too admitted to making up.

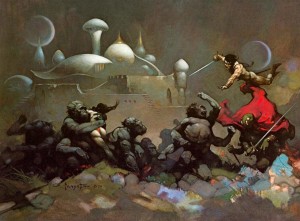

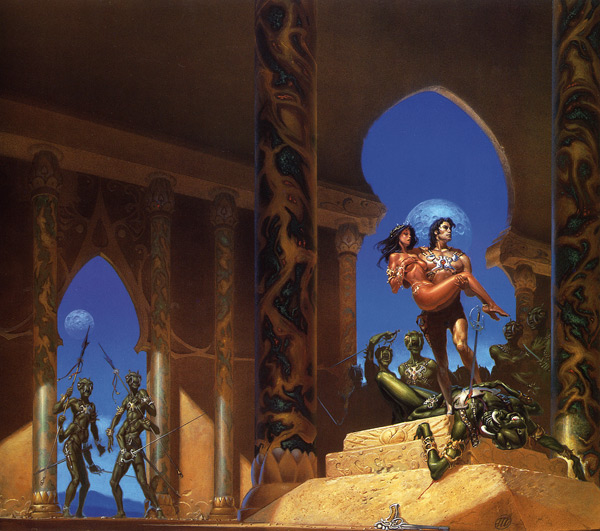

Based on the disguised description Lindner provides, it has been generally assumed that the sci-fi saga that obsessed and literally captivated his patient were Edgar Rice Burroughs’ stories about the Martian kingdom of Barsoom, which were first published in the pulps in 1912 and have remained popular to this day. But considerably adding to the interest and significance of Kirk Allen’s Martian adventures is his likely (although never conclusively proved) real identity. He is widely believed to have been, in actuality, the young Paul Linebarger, better known to generations of science fiction fans as Cordwainer Smith—one of the most interesting voices of mid-century sci-fi and a profound inspiration on younger writers like Ursula K. LeGuin. (And if his pictures are anything to go by, he was also about the least John Carter-ish person I could possibly imagine.)

Based on the disguised description Lindner provides, it has been generally assumed that the sci-fi saga that obsessed and literally captivated his patient were Edgar Rice Burroughs’ stories about the Martian kingdom of Barsoom, which were first published in the pulps in 1912 and have remained popular to this day. But considerably adding to the interest and significance of Kirk Allen’s Martian adventures is his likely (although never conclusively proved) real identity. He is widely believed to have been, in actuality, the young Paul Linebarger, better known to generations of science fiction fans as Cordwainer Smith—one of the most interesting voices of mid-century sci-fi and a profound inspiration on younger writers like Ursula K. LeGuin. (And if his pictures are anything to go by, he was also about the least John Carter-ish person I could possibly imagine.)

At the probable time of the therapeutic relationship described by Lindner, Lineberger’s day job was as a prominent government scientist, a specialist in psychological warfare working for the Pentagon; he had had an unusual upbringing in the Far East with somewhat close correspondences to what Lindner described for Kirk Allen. A psychologist named Alan C. Elms has written numerous blog posts and articles on Linebarger and evidently has done extensive research toward a definitive biography, and he has concluded that Linebarger indeed was probably Allen. It may make some sense of the truly far-out imagination of the writer known for his elegaic future histories of The Instrumentality of Mankind that he could have cut his chops writing excessive notes elaborating Burroughs’ elaborately envisioned alien empire.

Astral Travels

Assuming Kirk Allen was indeed Paul Linebarger/Cordwainer Smith, what makes the case triply interesting to me is the method of his fugue travels to this imagined/embellished alternate reality and how they matched the mode of travel used by his fictional alter ego.

At the beginning of Burroughs’ Mars saga, in what was eventually published in book form in 1917 as A Princess of Mars, we are introduced to the series’ hero John Carter. In that first novel, Carter begins as a Civil War veteran prospecting with a compatriot in Arizona; after his companion is killed by Indians, Carter takes refuge in a cave, where he falls asleep and experiences the classic symptoms of sleep paralysis: He awakens but finds his body frozen, hearing a noisy presence behind him that he cannot see. Eventually he gains use of his body, but finds that it is merely his astral body—his physical body is still lying on the cave floor.

At the beginning of Burroughs’ Mars saga, in what was eventually published in book form in 1917 as A Princess of Mars, we are introduced to the series’ hero John Carter. In that first novel, Carter begins as a Civil War veteran prospecting with a compatriot in Arizona; after his companion is killed by Indians, Carter takes refuge in a cave, where he falls asleep and experiences the classic symptoms of sleep paralysis: He awakens but finds his body frozen, hearing a noisy presence behind him that he cannot see. Eventually he gains use of his body, but finds that it is merely his astral body—his physical body is still lying on the cave floor.

In his astral body, Carter goes to the front of the cave, where he sees Mars on the horizon—as a warrior, it is his personal star—and he focuses his attention and will upon it: “I closed my eyes, stretched out my arms toward the god of my vocation and felt myself drawn with the suddenness of thought through the trackless immensity of space.” Through many adventures over ten years while his Earth body slumbers in the Arizona cave, the Martian avatar of John Carter, after awakening in Barsoom, marries a princess and eventually becomes its ruler.

According to Chris Knowles (in Our Gods Wear Spandex), this detail of astral projection (as well as numerous other motifs in Burroughs’ work) betray a likely familiarity with Theosophy, which made a big deal of this exact mode of locomotion across space. Writers on the subject frequently noted astral projection’s continuity with what was then called “catalepsy”—i.e., waking up paralyzed, experiencing vibrations and frightening noises, and only with difficulty separating the astral body from the physical, just as Burroughs describes. Otherwise, Burroughs would have had to have a direct personal experience with journeying out of his body, as his account of the experience is highly “realistic,” as anyone who has suffered sleep paralysis and its occasional out-of-body sequelae knows. Also, traveling etherically or astrally is described in all the literature on the subject as a simple matter of willing one’s astral body to the location desired.

Crucially, this same method is followed by Lindner’s patient Kirk Allen in the dissociative states that led him to be referred for psychiatric help. Allen describes to the doctor how, when he got to the end of the series of novels—which had essentially (he thought) been describing his own life—he went ahead and began writing the continuation of his interplanetary life story. It started as a vivid anamnesis, a method he says he developed of distinguishing imagination and recall—literally “remembering” facts of his alter-ego’s ongoing biography as though they were his own memories. But at one point, while working on a map of the distant empire he ruled, he found himself unable to remember a significant detail from a photograph taken on one of his adventures but filed away (he knew) in a locked room inside his palace on the distant planet. He felt a sense of frustration that he couldn’t remember it accurately.

“I thought of those blasted photographs stuck away there in a place no one but I could get to. I wracked my brains trying to recall the landscape I had flown over, and the pictures I had glanced at casually before putting them away. No use. I was furious. I cursed myself for not looking at them more closely when I had them. And then I thought: ‘If only … if only I were there, right now, I would go directly to those files and get those pictures!”

“No sooner had I given voice to this thought than my whole being seemed to respond with a resounding ‘Why not?’—and in that same moment I was there.”

He describes how, finding himself fully within the body of his alter ego, he rose and went to the secret room in his palace and looked at the pictures he had been remembering.

“It was over in a matter of minutes, and I was again at the drawing board—the self you see here. But I knew the experience was real; and to prove it I now had a vivid recollection of the photographs, could see them as clearly as if they were still in my hands, and had no trouble at all completing the map.

“You can imagine how this experience affected me. I was stunned by it, shaken to the core, but excited as I had never been. In some way I could not comprehend, by merely desiring to do so, I had crossed the immensities of Space, broken out of Time, and merged with—literally become—that distant and future self whose life I had until now been remembering. Don’t ask me to explain. I can’t, although God knows I’ve tried! Have I discovered the secret of teleportation? Do I have some special psychic equipment? Some unique organ or what Charles Fort called a ‘wild talent’? Damned if I know!”

Note that “immensity of space” is the phrase used by Burroughs too to describe the psychic crossing. Here again, the method as well as the strong emotions coming with it strongly resemble accounts from psychic research of astral travel/OOBEs—specifically the astonished excitement—as well as the sense of “verification” that it brought him. In this case, of course, there is little possible or plausible objectivity to this verification, since he was traveling to a place we are to assume never existed but in the pages of Burroughs’ novels. Or did his obsession create a kind of tulpa of Barsoom?

Note that “immensity of space” is the phrase used by Burroughs too to describe the psychic crossing. Here again, the method as well as the strong emotions coming with it strongly resemble accounts from psychic research of astral travel/OOBEs—specifically the astonished excitement—as well as the sense of “verification” that it brought him. In this case, of course, there is little possible or plausible objectivity to this verification, since he was traveling to a place we are to assume never existed but in the pages of Burroughs’ novels. Or did his obsession create a kind of tulpa of Barsoom?

The Fractal Geometry of Paul Linebarger

If we are not enough dizzied by the spirals of alter-egos and pseudonyms in Paul Linebarger’s (probable) life story—Linebarger believing himself to be John Carter of Mars and disguised by his therapist as Kirk Allen, ultimately to adopt the pen name Cordwainer Smith—there is also here a dizzying recursiveness of the mode of travel between real and imaginal and fictive worlds that is layer- or onion-like: a fractal geometry of reading and writing, imagination and anamnesis, influences and inspirations and revision and re/unnaming. What (the f***) are we to make of this? Is something trying to hide? Or is something trying to be born?

It does seem like Linebarger/Smith/Allen had a lot he felt he needed to hide. Besides his constant astral projecting into a fictional universe, he also appears to have had sexual hangups and gender quirks that his era was not ready for. According to Elms (in an interesting article in the journal Science Fiction Studies called “Building Alpha Ralpha Boulevard”), Linebarger alienated his first wife by assuming a female alter-ego in some of his early writing and by cross-dressing in her presence. Nothing like this appears in Lindner’s chapter on Kirk Allen, but Lindner does interpret his divorce from reality as a defense against normative sexuality in the aftermath of an adolescent semi-trauma of being used sexually by an older woman. Lindner reports that his patient had had no further sexual experiences since adolescence and that on one occasion he astrally projected to his distant planet to avoid a sexual encounter with a female scientist colleague he had been platonically dating.

It does seem like Linebarger/Smith/Allen had a lot he felt he needed to hide. Besides his constant astral projecting into a fictional universe, he also appears to have had sexual hangups and gender quirks that his era was not ready for. According to Elms (in an interesting article in the journal Science Fiction Studies called “Building Alpha Ralpha Boulevard”), Linebarger alienated his first wife by assuming a female alter-ego in some of his early writing and by cross-dressing in her presence. Nothing like this appears in Lindner’s chapter on Kirk Allen, but Lindner does interpret his divorce from reality as a defense against normative sexuality in the aftermath of an adolescent semi-trauma of being used sexually by an older woman. Lindner reports that his patient had had no further sexual experiences since adolescence and that on one occasion he astrally projected to his distant planet to avoid a sexual encounter with a female scientist colleague he had been platonically dating.

Linebarger’s fiction does seem to me to be the work of a misfit very like the young Kirk Allen, comfortable with ideas and books and cats and alien cultures … and talking cats … but totally ill at ease in his own skin. For instance, his 1945 story “Scanners Live in Vain” (which would have been written not too many years after his therapy with Lindner, if he was indeed Kirk Allen) is about star pilots who endure the agony of space by severing all contact with their bodies, living like numb automata:

“The brain is cut from the heart, the lungs. The brain is cut from the ears, the nose. The brain is cut from the mouth, the belly. The brain is cut from desire, and pain. The brain is cut from the world. Save for the eyes.”

The button-down era when Kirk Allen visited Lindner was light years distant from our world of SF fandom, with its exuberant embrace of creative rewriting in the form of fanfic, as well as various forms of online and real-world role-play. At the time, the young man’s active fantasy life and lifestyle could only have been seen as full-on nuts, and Lindner is not at all embarrassed to use terms like “insane” and “mad” when describing him. The lack of any accepted cultural form or idiom for expressing his identification with a fictional (super)hero ensured that his ecstasies or reveries (or whatever we want to call them) remained an embarrassing private pathology whose intrusion on his professional or romantic/sexual life could only be damaging. Perhaps some future Foucault of the mystical could tell us whether this medicalized repression of Linebarger’s creative relationship to Burroughs’ fiction was actually ‘productive’ of something in the way of sexual desire, creative verve, or even psychical ability. Might the non-social-acceptability of his obsessions have facilitated some kind of psychic or mystical wild talent that today’s slightly more liberal atmosphere would have the effect of neutralizing?

Fitting in to one’s society is an important part of happiness, so Kirk Allen’s astral traveling to the self-created tulpa of Barsoom was certainly an impediment to his life. In Lacanian terms, his literary-imaginative jouissance had to be curtailed, subjected to the sociable logic of the pleasure principle, to restore him to health. But while we do get the sense that something in him was indeed cured, freed to progress in a more “normative” (in I suppose a good way) direction—which would enable him to thrive, have a family, pursue a writing career, etc.—one cannot read Lindner’s account nowadays and not feel that something extraordinary may have been killed in the process. We’ll never know if Lindner’s unorthodox treatment enabled the subsequent brilliant (but still too-obscure) career of Linebarger/Smith or inhibited it, and what other possibilities (or wild talents) it may have curtailed or redirected, for better or worse. Had Linebarger/Smith been able to consult a priest or a shaman instead of being referred to a psychiatrist for his habit of astral traveling to Barsoom, his life and his creativity may have turned out very differently.

I do think it may be significant that Linebarger’s stories (as Cordwainer Smith) are set during or in the immediate aftermath of a milliennia-long period of Galactic peace—really, crushing bland conformity and a despiriting absence of danger and illness—under the “benevolent” totalitarian control of “The Instrumentality of Mankind.” I wonder if, like many creative spirits, Linebarger linked his muse to his psychic pain or ‘abnormality’ and thus had an ambivalent attitude to the psychotherapeutic cure(s) that had rectified and normalized his existence.

I do think it may be significant that Linebarger’s stories (as Cordwainer Smith) are set during or in the immediate aftermath of a milliennia-long period of Galactic peace—really, crushing bland conformity and a despiriting absence of danger and illness—under the “benevolent” totalitarian control of “The Instrumentality of Mankind.” I wonder if, like many creative spirits, Linebarger linked his muse to his psychic pain or ‘abnormality’ and thus had an ambivalent attitude to the psychotherapeutic cure(s) that had rectified and normalized his existence.

Whatever the case, the story of Linebarger/Allen is a complex maze of hidden and deferred identities, transferrences and countertransferrences, and redirected/sublimated sexuality. There is something powerful at work here, some model of the intersections of psychosexual exploration and creativity and mysticism and popular culture that relates to but also goes way beyond Bloom’s Gnostic/Freudian theory of misreading. All I know is, there is so much more I want to know about Paul Linebarger. On his blog, Elms promises he is writing a biography, although it appears it has been imminent for over a decade. I know too well how those types of projects go…

The Martian Imaginal

We can fit the curious case of Kirk Allen/Paul Linebarger within a long, fascinating, bizarre history of psychic engagement with the Red Planet (or the “Martian imaginal”). Books have been written on Mars’s place in our collective fantasies and in popular culture. A few key points include Helene Smith’s mediumistic communication with that planet in the late 19th century, described in Pierre Flournoy’s book From India to the Planet Mars. In turn-of-the-century sci-fi, there was, apart from Burroughs’ novels, also obviously H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, which later intruded on everyday reality through Orson Welles famously realistic radio adaptation.

Then after Kirk Allen, there was comic artist Jack Kirby’s eerily prophetic anticipation of the “face on Mars” in a 1959 comic book, 17 years before the Viking probe photographed such an object. Later, thanks to Sagan, Mars played an arguably decisive role in galvanizing public attitudes toward nuclear weapons in the last decade of the Cold War, as its dust storms provided the astronomer with his idea and model of “nuclear winter.” Anomalists continue to speculate about the existence of an ancient civilization that destroyed itself or was destroyed in Mars’s watery past. Among the planets of our solar system, Mars is uniquely not only a mirror but, arguably, a psychic player in our culture and history.

Then after Kirk Allen, there was comic artist Jack Kirby’s eerily prophetic anticipation of the “face on Mars” in a 1959 comic book, 17 years before the Viking probe photographed such an object. Later, thanks to Sagan, Mars played an arguably decisive role in galvanizing public attitudes toward nuclear weapons in the last decade of the Cold War, as its dust storms provided the astronomer with his idea and model of “nuclear winter.” Anomalists continue to speculate about the existence of an ancient civilization that destroyed itself or was destroyed in Mars’s watery past. Among the planets of our solar system, Mars is uniquely not only a mirror but, arguably, a psychic player in our culture and history.

But more to my point, rather than trying to erase and rewrite his predecessor Burroughs’ engagement with that planet, the young Linebarger seems to have been happy inhabiting it, and evidently was only driven to creatively elaborate or embellish it because it ended too soon, before his “biography” was complete. Thus, to what extent does “anxiety of influence” really apply here? There is no way of answering that for certain without seeing the notes he created (and that Lindner himself got lost in). But Kripal’s picture of “fantastic loops” seems more apt: It is not simply the anxious creative genius that is wrestling with and distorting his/her predecessors; it is cultural forms, created (imperfectly) out of remarkable personal experiences—and also shaped and constrained by countless other cultural forces and semiotic systems—that distort or twist some pure current, which a budding artist was really trying to do justice to and honor even though he was an imperfect vessel in an imperfect world.

In other words, I see Kirk Allen/Paul Linebarger as genuinely trying to channel something that does not belong to him, and to actually get it right, and attempting in various ways to actually efface his ego in the process. Kripal has noted that mystical and psychic phenomena like clairvoyance and precognition are intimately connected to writing. The case of Kirk Allen, like that of Allen Ginsberg, suggests it’s clearly also connected to “spirit possession” in some, perhaps not completely literal, sense.

The creative and the mystical or paranormal (or some indeterminate category where it is hard to tell what is really going on) is some kind of universal nexus in the domain of cultural creativity, and Bloom’s “revisionism” maps just one small segment of a much wider and more interesting spectrum of creative (to put it mildly) reader response.

Eric, I really appreciate this entry. I read the 2013 piece on Linebarger/Smith by Ted Giao in *The Atlantic*, and that prompted me to pull my old copy of *The Best of Cordwainer Smith* (1975. Ed. J.J. Pierce. Science Fiction Book Club)down from the shelf and read through all of those stories (it overlaps, but not completely, with the 1985 collection *The Instrumentality of Mankind*).

I had strong impressions of those stories from much more useful readings, and I was pleased to find out that I still thought those stories, written between 1950 and 1966, were strong, strong, strong, both in terms of ideas and language — and humanity.

According to the prefaratory note to *The Best of* by J.J. Pierce, Linebarger was born in Milwaukee in 1913, but grew up in China, Japan, France, and Germany. His a father was a financier of the 1911 Chinese revolution, and Linebarger was the godson of Sun Yat Sen, who gave Linebarger the name “Lin Bah Loh,” or “Forest of Incandescent Bliss”. He spent WWII in Chungking (sic) as a Lieutenant and finished up a Major, wrote an important book, *Psychological Warfare,* and remained a big deal in foreign policy circles, including being an adviser to JFK. Pierce’s notes indicate that he was a behind-the-scenes international bad-ass for pretty much his whole life.

Interestingly, in terms of the gender-fluidity, while he was in China during the war, he wrote two “psychological” novels which were written from the perspective of female characters. (All this material from Pierce, 1975, pp. 1-5).

I completely agree that Linebarger/Smith is under-appreciated. Earlier, outside, reading this post on my Kindle, it occurred to me that if you wanted to “cross” metaphors based on the “opera” in “space opera” (which Smith certainly was writing!), then Smith would be on a level with Giaccomo Puccini. I thought this before I re-read the intro notes to “Best of” and was reminded just how much of a sinologist Smith was; Puccini’s masterpiece *Turandot* famously being a musically transitional (that is, a leap forward in “style” for opera) story about China (and hands-down my favorite opera).

I have to say, I come away from this brief re-reading of his biographical notes being skeptical of just how closely Lindner’s description of “Kirk Allen” actually hewed to Linebarger’s presentation to Lindner (assuming that Linebarger really did for the basis for “Kirk Allen,” which I’m not disputing). For one thing, it apparently leaves out or ignores the depth provided by Linebarger’s international upbringing and early functionality at high levels (Linebarger earned a Ph.D. in political science, focused on China, from Johns Hopkins at 23) and his high-functioning throughout his life.

Rather than concluding that Lindner was shooting straight about having “fixed” Allen (and thus perhaps stunting some nascent new creativity), I think it’s almost equally as likely to conclude that Linebarger somehow successfully “integrated” and “fired” Lindner by saying “I made it all up.” Maybe he read Henry Murray.

Who’s to say that Allen/Linebarger, with some new-found confidence (I mean, the guy wrote a job description for the army that only he could fill, spent WWII in China and wrote a seminal book on psy-ops that is still considered a classic – Pierce ’75), said “to hell with this” to Lindner’s ‘therapy’, and somehow kept on practicing something like “active imagination” (as Tolkien apparently also did in coming up with his opus – can’t remember whether I read that first in your essays, Gordon White’s, or Chris Knowles’) and go on to do the things he did? He was a significant international player, and I would argue that his literary output was * extremely * * powerful * .

Interestingly, in terms of Linebarger’s early science-fictional influences, Pierce mentions Verne, Wells, Doyle, and some to-us-obscure Germans – but not Burroughs.