Altered States of Reading (4): Ginsberg & the End of the Bookstore

Ralph Waldo Emerson warned, in his essay “Self-Reliance,” about the failure of most people to notice and follow their inner light or spark: “A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought, because it is his.” In other words, we don’t pay attention to our own unique genius simply because it is our own—belonging to little old me, some dumb schlub.

The result of this self-denial is a particularly disappointing reading experience that is all-too-common if you have any kind of aspiration to express yourself originally: “In every work of genius,” Emerson writes, “we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.” We are, when that happens, “forced to take with shame our own opinion from another.”

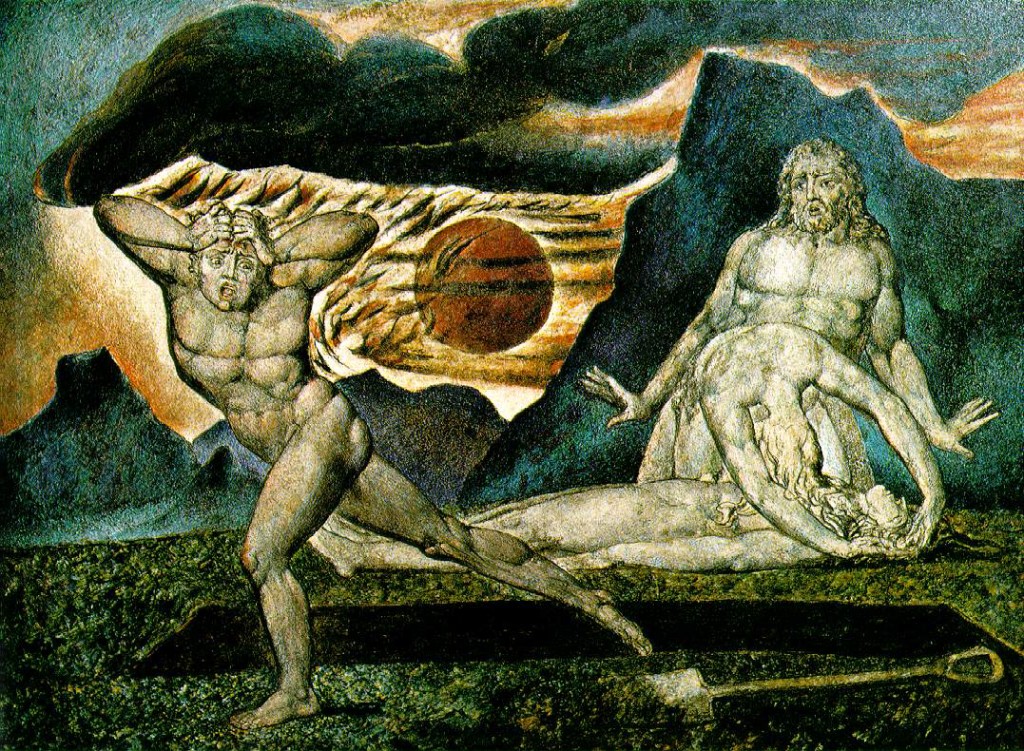

This frustrating experience of being scooped by some other writer is the kernel from which Harold Bloom spun a whole Gnostic-Freudian theory of literary criticism: Forget that the book we are reading may have been written years or centuries before we were even born; the unconscious has no sense of time. A strong or worthy writer (Bloom argues) feels deeply threatened by the texts that resonate most strongly with what he himself has to say, and those texts thus radiate with fascinating/horrifying sublimity, an “alienated majesty” (as Emerson put it), that must be resisted at all costs. Out of this feeling, what Bloom calls the “anxiety of influence,” the truly original creative genius feels driven by a competetive-destructive spirit that is another version of the son’s Oedipal wish to kill his father and replace him.

The energy of literary creation, in other words, is competetiveness arising from a desperate refusal of the writer’s own belatedness. This need to be original also distorts the writer’s reading of his predecessors; in the course of several books, Bloom applied this to the world of poetry and created what he called a “map of misreading”—a start toward a kind of literary genealogy of influence and its anxious defenses from literary fathers to their sons down through the centuries. When broadened beyond the narrow sphere of poetry, Bloom’s theory of literary revisionism offers a useful Freudian theory of cultural innovation that can be applied to many domains. I even suspect this precise anxiety may fuel precognitive experiences among writers who are unconsciously trying to scoop each other, as I have discussed in previous installments.

The energy of literary creation, in other words, is competetiveness arising from a desperate refusal of the writer’s own belatedness. This need to be original also distorts the writer’s reading of his predecessors; in the course of several books, Bloom applied this to the world of poetry and created what he called a “map of misreading”—a start toward a kind of literary genealogy of influence and its anxious defenses from literary fathers to their sons down through the centuries. When broadened beyond the narrow sphere of poetry, Bloom’s theory of literary revisionism offers a useful Freudian theory of cultural innovation that can be applied to many domains. I even suspect this precise anxiety may fuel precognitive experiences among writers who are unconsciously trying to scoop each other, as I have discussed in previous installments.

Bloom’s theory makes great sense of poetic and cultural creativity in the world of what might be called alpha creatives, who are generally male and who are universally obsessed with their own reputation and legacy—and this applies a bit to everyone insofar as we are humans and have egos and try to protect them. But I think it also may cause us to overlook more outrageous and even mystical altered states of reading in which the reader/writer’s ego is more permeable and receptive to “transmission” from literary forebears.

Ginsberg’s Initiation

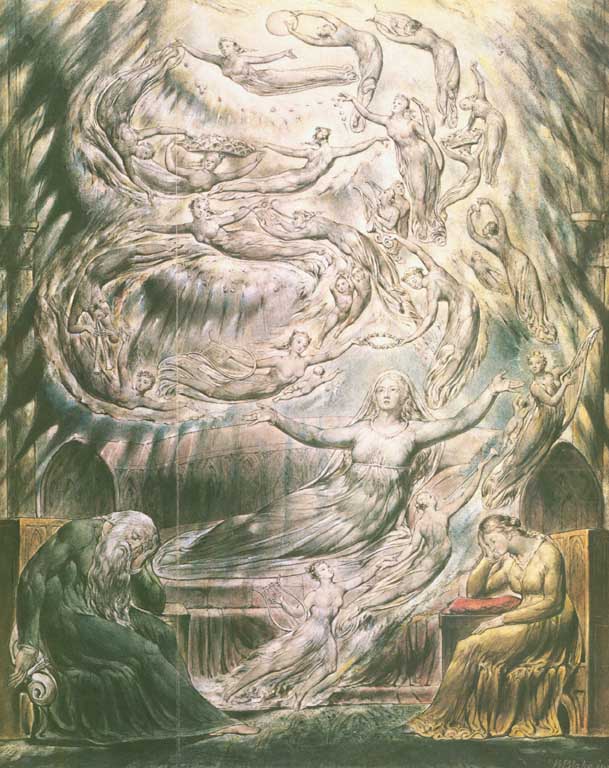

If I could take any one piece of mystical writing and thrust it people’s hands and urge them to read it with all my pleading force, it would not be any of the spiritual classics or Zen writings piled in my study but, of all things, Allen Ginsberg’s 1966 interview in the Paris Review, in which the poet describes at great length a profound mystical state he experienced in 1945 while a student at Columbia University. I’ve read lots of accounts of ecstatic experiences, but this one gets me the most—it’s a touchstone I’ve returned to again and again since I first read it two and a half decades ago, not only for the beauty of Ginsberg’s insights but also for the simple humor and humanity with which he depicts the transfigured reality he experienced during a few ecstatic days as a young man.

Ginsberg is disarmingly blunt in his description: It began, he said, just after he had masturbated while idly reading the poetry of William Blake in his room. I quote at length:

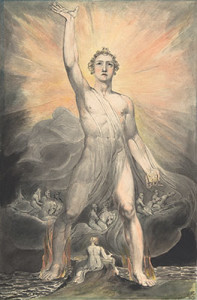

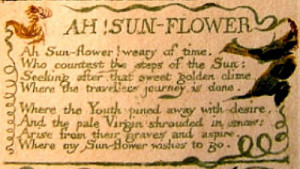

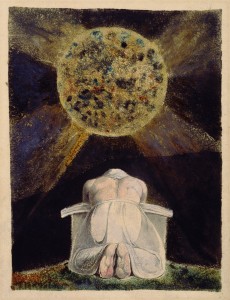

And just after I came, on this occasion, with a Blake book on my lap—I wasn’t even reading, my eye was idling over the page of The Sunflower, and it suddenly appeared—the poem I’d read a lot of times before, overfamiliar to the point where it didn’t make any particular meaning except some sweet thing about flowers—and suddenly I realized that the poem was talking about me. “Ah, Sun-flower! weary of time, / Who countest the steps of the Sun; / Seeking after that sweet golden clime / Where the traveler’s journey is done.” Now, I began understanding it, the poem while looking at it, and suddenly, simultaneously with understanding it, heard a very deep earth graven voice in the room, which I immediately assumed, I didn’t think twice, was Blake’s voice … But the peculiar quality of the voice was something unforgettable because it was like God had a human voice, with all the infinite tenderness and anciency and mortal gravity of a living Creator speaking to his son. “Where the Youth pined away with desire, / And the pale Virgin shrouded in snow / Arise from their graves, and aspire / Where my Sunflower wishes to go.” … [L]ooking out at the window, through the window at the sky, suddenly it seemed that I saw into the depths of the universe, by looking simply into the ancient sky. The sky suddenly seemed very ancient. And this was the very ancient place that he was talking about, the sweet golden clime, I suddenly realized that this existence was it! And that I was born in order to experience up to this very moment that I was having this experience, to realize what this was all about—in other words that this was the moment that I was born for. This initiation.

It is an experience and an insight that has been described countless times in spiritual literature, but what is unique in Ginsberg’s account are the particulars, the humor and specificity of it, and his linking it specifically to the act of reading and the mundane economy of books and learning, which lend it an authenticity and immediateness that more culturally or historically distanced accounts may lack.

It is an experience and an insight that has been described countless times in spiritual literature, but what is unique in Ginsberg’s account are the particulars, the humor and specificity of it, and his linking it specifically to the act of reading and the mundane economy of books and learning, which lend it an authenticity and immediateness that more culturally or historically distanced accounts may lack.

Ginsberg goes on to describe visiting the campus while in his transcendent frame of mind and his realization, upon leafing through another Blake book in the university bookstore, that this cosmic awareness is actually shared by everyone but that we hide it from ourselves and each other through the masks we wear. Again I quote at length:

I was in the eternal place once more, and I looked around at everybody’s faces, and I saw all these wild animals! Because there was a bookstore clerk there who I hadn’t paid much attention to, he was just a familiar fixture in the bookstore scene … But anyway I looked in his face and I suddenly saw like a great tormented soul—and he had just been somebody whom I’d regarded as perhaps a not particularly beautiful or sexy character, or lovely face, but you know someone familiar, and perhaps a pleading cousin in the universe. But all of a sudden I realized that he knew also, just like I knew. And that everybody in the bookstore knew, and that they were all hiding it! They all had the consciousness, it was like a great unconscious that was running between all of us that everybody was completely conscious, but that the fixed expressions that people have, the habitual expressions, the manners, the mode of talk, are all masks hiding this consciousness. Because almost at that moment it seemed that it would be too terrible if we communicated to each other on a level of total consciousness and awareness each of the other—like it would be too terrible, it would be the end of the bookstore … in other words the position that everybody was in was ridiculous, everybody running around peddling books to each other. Here in the universe! Passing money over the counter, wrapping books in bags and guarding the door, you know, stealing books, and the people sitting up making accountings on the upper floor there, and people worrying about their exams walking through the bookstore, and all the millions of thoughts the people had—you know, that I’m worrying about—whether they’re going to get laid or whether anybody loves them, about their mothers dying of cancer or, you know, the complete death awareness that everybody has continuously with them all the time—all of a sudden revealed to me at once in the faces of the people, and they all looked like horrible grotesque masks, grotesque because hiding the knowledge from each other. Having a habitual conduct and forms to prescribe, forms to fulfill. Roles to play. But the main insight I had at that time was that everybody knew. Everybody knew completely everything. Knew completely everything in the terms that I was talking about.

The Interhuman Church

Ginsberg’s ecstatic realization in the bookstore reminds me a lot of my favorite Polish writer, novelist and diarist Witold Gombrowicz, who throughout his work described masks as a way of managing the danger of human contact. (The most hilarious and memorable scene in his debut novel Ferdydurke, for instance, is a “grimace war” between two schoolkids.) Gombrowicz elevated the power and danger of other people into a kind of fetishistic religion, what he called the “interhuman church.” Throughout his writing he focused on the perverse ways people try to extract the energy of contact from others without paying their social dues, and how the forms through which we express ourselves are always these dishonest bottlings of our latent energy. (His stories and novels are weirdly like Seinfeld episodes from a different, much more uptight era.)

As I’ve written elsewhere on Gombrowicz: “Humanity has devised a billion ways of not contacting each other. Everything you look at, everything we’ve done or accomplished, can be seen as a way of avoiding contact. The Hebrews of the Old Testament kept God behind a curtain because to be in his presence, they thought, was fatal. I think really being in the presence of the human is fatal, so we create structures, channels, protocols, machines, to redirect the energy, redirect ourselves, and protect ourselves.”

An interesting thing happens when you bottle the interhuman Real: It evolves a Form, just as an influx of energy does in any physical system. Forms—cultural forms, biological forms, behaviors, you name it—become possibilized, rationalized, rechanneled into acceptable constructs or formations that are, when you really peer in close (like peering into the grass in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet) seething with instability and danger. Cultural forms like art and poetry (and science and politics) are temporary unstable solutions, just as the individual ego is. We utterly depend on these constructs to contain the outrageous energies that are in us and that precede and surround us. Sometimes in the midst of visionary experiences, as in Ginsberg’s case, we have an insight into this fact, and see the human pathos behind the masks we wear and the systems we erect to protect us from the jouissance of the human Real.

An interesting thing happens when you bottle the interhuman Real: It evolves a Form, just as an influx of energy does in any physical system. Forms—cultural forms, biological forms, behaviors, you name it—become possibilized, rationalized, rechanneled into acceptable constructs or formations that are, when you really peer in close (like peering into the grass in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet) seething with instability and danger. Cultural forms like art and poetry (and science and politics) are temporary unstable solutions, just as the individual ego is. We utterly depend on these constructs to contain the outrageous energies that are in us and that precede and surround us. Sometimes in the midst of visionary experiences, as in Ginsberg’s case, we have an insight into this fact, and see the human pathos behind the masks we wear and the systems we erect to protect us from the jouissance of the human Real.

Ecstasy is another possible translation for jouissance: a feeling so excessive that it actually takes us out of our bodies (ecstasy comes from ek-stasis, to stand out or aside). The way language and social rules, including manners and structures of social interaction, function as a Symbolic screen against the interhuman Real is seen clearly in situations when those structures and rules are surgically removed.

Performance artist Marina Abramovic’s 2009 installation at MOMA, “The Artist Is Present” is probably the best example. For three months, gallery visitors could sit silently across from the artist in the gallery and gaze into her eyes. As shown in the film documenting this piece, many visitors were overwhelmed with emotion at this unmediated presence of another person; the experience seems to have been a religious one for many. It is essentially identical to the experience of receiving darshan (or “auspicious sight”) in the Hindu tradition: a gaze or a hug by a great guru or holy person that can provoke an ecstatic experience in the recipient. For a few months “The Artist Is Present” became the thing to experience in New York.

It may not matter that the giver of darshan is a guru or famous artist. L. Ron Hubbard clearly understood the power latent in interhuman contact for liberating our untapped potential. There is an early exercise in Scientology training in which participants sit across from each other without speaking (it is even depicted in Paul Thomas Anderson’s movie The Master). According to John L. Wilhelm (The Search for Superman), SRI psychic extraordinaire Pat Price traced his unique psi gifts to an out-of-body experience provoked by precisely this exercise. Jason Beghe reports in Alex Gibney’s Scientology documentary Going Clear that it had the same effect on him (even if without the psychic sequelae). So explosive is another human being’s mere presence, in other words, that just facing one without the usual social mores that structure our social encounters has the potential of actually liberating us from our bodies.*

Humanity is strong stuff.

Reading, Psi, and the Body

I have never had a full-on religious experience like Ginsberg’s while reading a book or wandering around a bookstore, but I’m no stranger to less extreme altered states of reading. The “intellectual high” is a real thing, for example: In the excitement of reading a particularly mind-blowing passage in a book I have often experienced semi-out-of-body experiences, where I feel myself to be drawn toward the text in front of me, hovering in the space between my face and the page—an odd body-dysmorphic feeling of being italicized. I assume other readers experience this slight dissociation. The joy of uniquely mind-bending writers like Phil Dick or Slavoj Žižek is not unlike that of Zen koans: to force a conceptual rupture and a mild ek-stasis.

Even if a text does not seem literally about me, I also know the experience of hearing the words spoken in my head as though by the author; I’m surely not unusual in this, either. There is some way in which, in a state of intellectual excitement, the book in front of you—or the screen you’re reading on, or whatever the medium through which you engage with a text—is not enough; you want to pass into and through it, or you believe some direct communion with the author is possible. That frustration may in fact widen the aperture of psi.

Even if a text does not seem literally about me, I also know the experience of hearing the words spoken in my head as though by the author; I’m surely not unusual in this, either. There is some way in which, in a state of intellectual excitement, the book in front of you—or the screen you’re reading on, or whatever the medium through which you engage with a text—is not enough; you want to pass into and through it, or you believe some direct communion with the author is possible. That frustration may in fact widen the aperture of psi.

Jacques Vallee observed ESP effects in experiments he set up in the 1970s using computer networks. The sense of frustration at communicating through narrow channels of electronic mail and chat systems, on a keyboard and screen, produced what looked to him like real telepathy (although I’d suggest, without knowing the details, that it could really have been precognition of imminent confluences/coincidences of thoughts as manifested on the participants’ screens). Psi particularly seems to manifest when there is particular urgency and when ordinary modes of communication are unavailable or felt to be too-limiting. For me, precognition manifests routinely, almost daily, around Twitter, email, and the specific mild frustrations of following unfolding news events online.

I suspect mildly anomalous experiences of aesthetic or intellectual excitement that distort our psychic spacetime, as well as feelings of psychic connection to an author, are quite common yet are seldom discussed or described, simply because we lack a vocabulary for them. These small experiences are just one end of a continuum that includes the powerful sublime ecstasies that interest religion scholars like Jeffrey Kripal—a spectrum of energetic distortion of the powerfully enthralled or engaged bodymind that is conducive to psi.

A Time Machine

How many college students must experience similar things to what Ginsberg did: ecstatic states inspired by something profound they have read during that reading-intense four or so years of their lives—and perhaps even wandered through their campuses in an inspired haze, ending up in the bookstore—but lack sufficient cultural/spiritual/literary coordinates to triangulate the experience and articulate it to themselves, let alone others? How many such experiences are thus completely or mostly forgotten?

Fortunately for Ginsberg, he did have the necessary coordinates, thanks to his education and upbringing and interesting friends, as well as an ambition to become one of those people sharing their cosmic insights. “[M]y first thought,” Ginsberg says, “was this was what I was born for, and second thought, never forget—never forget, never renege, never deny. Never deny the voice no, never forget it, don’t get lost mentally wandering in other spirit worlds or American or job worlds or advertising worlds or war worlds or earth worlds. But the spirit of the universe was what I was born to realize.”

Fortunately for Ginsberg, he did have the necessary coordinates, thanks to his education and upbringing and interesting friends, as well as an ambition to become one of those people sharing their cosmic insights. “[M]y first thought,” Ginsberg says, “was this was what I was born for, and second thought, never forget—never forget, never renege, never deny. Never deny the voice no, never forget it, don’t get lost mentally wandering in other spirit worlds or American or job worlds or advertising worlds or war worlds or earth worlds. But the spirit of the universe was what I was born to realize.”

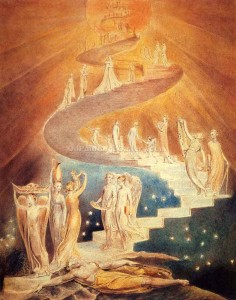

For the young poet, the experience of finding himself addressed and described in a text by Blake, lying on his bed with his fly unzipped, was nothing less than a transmission across time and space from the English mystic, bestowing an inheritance and a mission that he explicitly compared to the Zen fifth patriarch giving the begging bowl symbolic of his status to his successor Hui-Neng. He says:

The thing I understood from Blake was that it was possible to transmit a message through time that could reach the enlightened, that poetry had a definite effect, it wasn’t just pretty, or just beautiful, as I had understood pretty beauty before—it was something basic to human existence, or it reached something, it reached the bottom of human existence. But anyway the impression I got was that it was like a kind of time machine through which he could transmit—Blake could transmit—his basic consciousness and communicate it to somebody else after he was dead …

This “time machine” experience of literary transmission bestowed upon a lonely young student/poet in his little New York apartment a whole destiny to be the ecstatic American poet-prophet of the Self in the tradition of Whitman. It is a destiny that he went on to fulfill brilliantly.

I am not enough of a literary scholar to be able to tell whether the Bloomian features of misreading (of Blake, of Whitman) are evident in Ginsberg’s poetry, and Ginsberg was oddly overlooked by Bloom despite wide critical consensus that he belongs firmly in the “Western Canon.” But I have to think the emphasis on Freudian father-killing obscures a less “agonistic” channel of poetic-spiritual transmission. When I read Ginsberg’s exuberant, ecstatic poetry or even just his transcribed conversation, I detect a spring flowing unimpeded from somewhere else. It could be a universal cosmic inheritance that is being channeled by a particularly unhindered soul. It could simply be his own future, bigger, smarter, wiser self—which I have argued is the true identity of the Freudian unconscious and the real source of all our creativity.**

NOTES:

*It may be possible to extract some of this power just from staring at ourselves. The exercise of gazing into a mirror for a prolonged period, something I have always avoided because it feels unlucky, seems to produce interesting paranormal phenomena, as Chris Savia explored in this article.

**The scene of Ginsberg’s “transmission,” masturbating in his apartment, is appropriate. Slavoj Žižek often expresses the cynical-sounding Lacanian idea that sex is really masturbation with a partner. My argument that psi phenomena like telepathy may really be precognition with a partner probably sounds similarly cynical; but while it may ‘queer’ the Frederic Myers idea that psi is fundamentally about human connection across great distances, I think this hypothesis opens all kinds of new ways of thinking about the power of psi to enhance our “real world” connections to others.

Consider this: We can imagine a “lateral” psychic connection to other humans in the present moment, or we can realize that through such experiences we are being drawn toward tangible physical connection to other humans in our future. Without that IRL connection in the flesh (or the text), how can we ever know it was ‘telepathy’ in any case, and not some solipsistic fantasy (even if shared by both partners)? For me, that physical (or at least, physically mediated) connection to other human beings that psi orients us toward feels ultimately more redemptive, in any case.

I noticed that all great creations of humans’ semiotic imagination – literary and artisitic works – may produce a kind of dissociative detachment if you let yourself to be immersed in them. Some music, such as one by “Depeche Mode” or “Enigma”, may indeed lead one into (slightly) altered state of consciousness if being listened alone, in a state of relaxation. Even some talented paintings seem to have this effect, if one looks into them for long, “falling” into them.

It’s magick, I suppose. Ritals and ceremonies also work that way, driving one into “changed mind” if one allow oneself to “become lost” (intentionally) in them.