Look Back in Amber: Dream Paleontology as a New Gnosis

We are four-dimensional beings. As I argue in my new book Time Loops, our behavior at any given moment is shaped not only by the exigencies of that moment and what has preceded it, but also by what comes next; we are informed by things we will learn in our future, not just by what we know from our past. It goes by many names: Teleology is an old one; syntropy is a newer idiom; retrocausation is what they call it in physics. Whatever you call it, it is a basic principle shown in the precognition and presentiment experiments of parapsychologists like Dean Radin and Daryl Bem. But those experiments, I believe, just show us the tip of the iceberg of how we—and all creatures—inhabit time.

The retrocausation paradigm in quantum physics, coupled with advances in quantum biology and other fields, is opening the door to thinking scientifically about teleological causation, not as some nifty little add-on to the basic billiard-ball nature of biology, but as possibly even the very foundation of biology. Scale up quantum retrocausation in a complex nervous system and you have what humans are gifted with: the ability to orient toward future rewards unconsciously, as well as the ability to be guided by information across our lifespan, both past and future. The really interesting thing is, because we don’t believe in it or understand how such a thing could be possible, we invariably misinterpret the perturbations caused by information refluxing from our future. Consequently, we shoehorn anomalous experiences into some easier-to-think conceptual mold like “synchronicity” or telepathy, or (more likely) disregard those experiences altogether.

Parapsychologists sometimes talk about precognition (and other claimed psi abilities) as the bleeding edge of human potential. I think of it more as human actual: It is not simply some new superpower that, once unlocked, will give us a new ability to shape our destinies. Whenever we act intuitively or creatively, paying attention to what gets glossed “the unconscious,” we are already in tune with our precognitive natures. We have always been precognitive. The unconscious, the source of our dreams and art as well as our neuroses, is simply consciousness displaced in time.

Likewise, the boons of precognitive dreamwork go way beyond using the “power of premonitions” to avert trouble or guide ourselves toward success. Again our intuition already does that—keep listening to it. Rather—and this was the biggest surprise for me over the past several years of working with my dreams in the manner J. W. Dunne recommended—the rewards are spiritual. Precognition is a new gnosis, a path of insight, one that connects us with our higher—although I prefer to say longer—Self.

Because precognition can only be confirmed in hindsight (and dreams can only be studied after they have been written down), precognitive dreamwork is, ironically, a retrospective, archaeological or even “paleontological” endeavor. It is a venturing into one’s own past, but in a way that, you will find, literally has a creative power to shape that past. It is a way to simultaneously find and make the shape of our biography.

As a kind of gnosis, precognition comes complete with its own ecstasies, its “highs,” its altered states, that are astonishing … and what’s more, almost completely unprecedented. With the exception of certain moments in Phil Dick’s Exegesis, I’m not aware of any spiritual writings describing what precognitive dreamwork has offered me on a few occasions: the utterly sublime and illusion-shattering experience of actually recognizing my own time-looping intervention in my timeline.

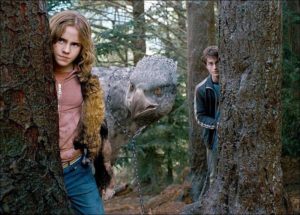

The best models for this experience are in SF and fantasy, where it is something of a staple. There is “Coop’s” attempt to contact his younger self via the tesseract in Interstellar, for instance, and the film Arrival, which I’ve discussed previously on this blog and also discuss in my book. Another vivid cinematic example I have been thinking about recently is the third Harry Potter film, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. I was not a huge Harry Potter fan, but Alfonso Cuaron handles time travel wonderfully in this film. Midway through, Hermione leads Harry several hours back in time using a “time turner” so they can rescue their slightly younger selves from a series of perils they had narrowly escaped in the first half of the movie. At each step of the way, they keep realizing that various anomalies they had experienced the night before (a rock hitting Harry in the head out of nowhere, a sound that distracted a werewolf pursuer, etc.) were themselves trying to get their own attention or otherwise save their own lives.

The best models for this experience are in SF and fantasy, where it is something of a staple. There is “Coop’s” attempt to contact his younger self via the tesseract in Interstellar, for instance, and the film Arrival, which I’ve discussed previously on this blog and also discuss in my book. Another vivid cinematic example I have been thinking about recently is the third Harry Potter film, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. I was not a huge Harry Potter fan, but Alfonso Cuaron handles time travel wonderfully in this film. Midway through, Hermione leads Harry several hours back in time using a “time turner” so they can rescue their slightly younger selves from a series of perils they had narrowly escaped in the first half of the movie. At each step of the way, they keep realizing that various anomalies they had experienced the night before (a rock hitting Harry in the head out of nowhere, a sound that distracted a werewolf pursuer, etc.) were themselves trying to get their own attention or otherwise save their own lives.

Dream journaling with an eye to precognition offers a real, literal time turner in which you can sometimes find yourself doing precisely this (albeit perhaps less dramatically than in Harry Potter): being a shaping presence in your own past. The reason is that the more attuned to dream precognition you become, the more you discover evidence of the phenomenon, and the more your amazement at these discoveries becomes included in your precognitive dreams. Your mature amazement becomes an influence in your life at an earlier point in time. I mean this quite literally.

The counterintuitive part, the “secret” if you will, is that that younger, naïve self is always unconscious; the dreamer does not, and by the laws of physics, cannot “know” what is going on, any more than the slightly younger Hermione and Harry know who is throwing rocks at their heads or rustling the bushes ahead of them. Sense—and again, a kind of vertiginous sublime epiphany—comes later, when the awake, conscious You goes back to the dream, in the form of your dream journal. The dream is not the time portal, the dream journal is. Its pages are the shale-like strata in which your most stunning paleontological discoveries are made. (This is why I keep telling you to keep a dream journal. Here, here’s a nice Amazon link to the particular journal I use for the purpose. You’re welcome.)

Let me illustrate the paleontological dream hermeneutic with a particularly striking example of mine from earlier this year.

Permian Battle

In late January, I wrote down a lucid dream that consisted of two parts. I’ll discuss the first later, but in the second part, my dream self was flying over a hillside, toward some large animals that seemed (from a distance) to be dinosaurs. This excited me greatly—I thought, how cool to visit a prehistoric landscape in a lucid dream! I was eager for a Jurassic Park-like experience. However, as I drew near, the creatures turned out not to be dinosaurs exactly but much more boring, squat, quadrupedal carnivores that I associated with some earlier period preceding the dinosaur era. The animal on my right in my dream was brown and vaguely dog-like, with a squarish head and saber-teeth; it was advancing on another creature, lumpy, squat, and black, more evil and reptilian-looking. They were about to clash in a fight, and landing between them, I had to intervene, holding the muzzles of both at arms’ reach as they tried to close on each other. Weirdly, there was a red dot, as from a laser pointer or laser gun-sight, fixed immovably on the body of the reptilian creature on my left, but I couldn’t turn my head to see what hunter was “targeting” it.

I jotted down notes on this in my notebook immediately on waking—it was probably around 6 AM—and then I wrote a couple paragraphs describing the dream in more detail in my electronic dream journal later that morning. The “fulfillment” of this dream came about 12 hours later, right after I checked my mail that evening.

The previous fall, I had purchased a subscription to a magazine called Prehistoric Times—a sort of quarterly “fan” magazine about dinosaurs, dinosaur art, and dinosaur culture (toys, collectibles, etc.)—partly because I like showing dinosaur pictures to my small daughter, but also out of increasing personal nostalgia for my own dinosaur-saturated childhood. When I checked my mail, I was pleasantly surprised to find the new (Winter 2018) issue of Prehistoric Times, my first issue since subscribing. It contained a feature about therapsids. Therapsids (I quickly learned) were the vaguely dog- or cat-like proto-mammals of the Permian period, the period preceding the dinosaur-dominated Mesozoic era. (I remembered such animals dimly from my childhood, as the boring early land carnivores shown at the beginning of some dinosaur books, preceding the exciting Mesozoic animals every kid is really interested in.)

The previous fall, I had purchased a subscription to a magazine called Prehistoric Times—a sort of quarterly “fan” magazine about dinosaurs, dinosaur art, and dinosaur culture (toys, collectibles, etc.)—partly because I like showing dinosaur pictures to my small daughter, but also out of increasing personal nostalgia for my own dinosaur-saturated childhood. When I checked my mail, I was pleasantly surprised to find the new (Winter 2018) issue of Prehistoric Times, my first issue since subscribing. It contained a feature about therapsids. Therapsids (I quickly learned) were the vaguely dog- or cat-like proto-mammals of the Permian period, the period preceding the dinosaur-dominated Mesozoic era. (I remembered such animals dimly from my childhood, as the boring early land carnivores shown at the beginning of some dinosaur books, preceding the exciting Mesozoic animals every kid is really interested in.)

The painting on the first page of the article—the one at the top of this post—was unmistakeably and stunningly the scene from my dream: It showed, side by side, exactly the two creatures that had moved to attack each other and that I had struggled to keep apart. From the caption I learned that the evil reptilian-looking one on the left was a scutosaurus and the saber-toothed therapsid on the right was a sauroctonus. The feature was specifically on therapsid paintings by the Czech illustrator Zdenek Burian, an artist from the middle years of the century whom I already knew and liked, but this was not a picture I had ever remembered seeing, nor did any books in my collection contain pictures of these creatures. Not only the two animals in my dream, but also the dream setting was exactly like that Burian painting—sort of a low hillside.

I have recorded a couple hundred dreams that I have identified as seeming precognitive—I have written about a handful of them in previous posts on this blog—but this was probably the most crystal-clear example of dream precognition so far in my life. No amount of Freudian free-association was necessary to unpack the dream’s connection to the next day’s experience. There were no puns or other substitutions. I quite literally dreamed that picture, with the embellishment that I was in the scene, interacting with those two animals. The only odd detail not in the actual picture was the laser dot. But that dot turned out to be the key to the time loop.

I initially scrutinized the various therapsid pictures in the magazine article, expecting maybe to find something like that dot, perhaps a printer’s blemish on one of the images. But all it took was a moment’s free-association to realize its significance: The first thing it reminded me of was the red dot of a laser gunsight on the forehead of Linda Hamilton in The Terminator, when Arnold Schwartzenegger first tries to assassinate her in a crowded bar. I hadn’t thought about that movie in years, yet what is that movie but a story about a hunter from the future traveling back in time to “target” someone in the past?

I initially scrutinized the various therapsid pictures in the magazine article, expecting maybe to find something like that dot, perhaps a printer’s blemish on one of the images. But all it took was a moment’s free-association to realize its significance: The first thing it reminded me of was the red dot of a laser gunsight on the forehead of Linda Hamilton in The Terminator, when Arnold Schwartzenegger first tries to assassinate her in a crowded bar. I hadn’t thought about that movie in years, yet what is that movie but a story about a hunter from the future traveling back in time to “target” someone in the past?

Recall that, in the dream, I couldn’t turn my head to see who was targeting this ancient creature. In fact, the out-of-sight hunter was me, about 12 hours ahead in my own timeline. The dream pre-presented my own retrospective scrutiny of these dream fauna from the point of view of amazedly, there on my living room couch, realizing that I myself was a time traveler, a hunter in my own past.* It was a dream pre-presentation of going back to the dream in hindsight.

Time Gimmickry

I have found, again and again, that dreams that turn out to have been precognitive often contain some representation of the act of returning to the dream to verify this fact. In other words, the precognitive nature of the dream is represented within the dream, like a fractal. “Time gimmicks” in dreams give the tip-off—elements having to do with time travel or “going back.” This includes rearview mirrors or juxtapositions of old and new. It only seems to happen, however, when the dream is recognized as precognitive at or near the time when the “confirming” event comes to pass, rather than at some time later. This is because dreams seem to be mnemonic (or pre-mnemonic) “bundles” binding experiences within a narrow window of time, usually an hour or two of waking life. If your realization that your dream was precognitive coincides with the experience being precognized, your realization will be included in the dream.

The above dream contained an additional time gimmick in addition to the laser dot. In an earlier part of that lucid dream, I had been zooming uncontrollably (I can never control my dream flight) through a vast enclosed cavern or gallery, like a vast subterranean hall, crowded with balconies that were densely packed with pale statues of ancient heroes—thousands of statues packed together on these balconies, almost like this enormous space had been converted into a storage facility for some huge trove of ancient marble statuary. I had a sense that some of the heroes were wearing helmets and light armor like ancient Greek or Roman warriors, but the only figure I remembered distinctly was an archer drawing back the string on his bow.

The above dream contained an additional time gimmick in addition to the laser dot. In an earlier part of that lucid dream, I had been zooming uncontrollably (I can never control my dream flight) through a vast enclosed cavern or gallery, like a vast subterranean hall, crowded with balconies that were densely packed with pale statues of ancient heroes—thousands of statues packed together on these balconies, almost like this enormous space had been converted into a storage facility for some huge trove of ancient marble statuary. I had a sense that some of the heroes were wearing helmets and light armor like ancient Greek or Roman warriors, but the only figure I remembered distinctly was an archer drawing back the string on his bow.

Given that the “Permian battle” scene was so clearly precognitive, I suspected this episode probably also pointed to the same magazine issue. I saw no obvious referent to such statuary later in the magazine (although the magazine did have several ads for superhero action figures). But when I flipped back to the beginning of the issue and paged through it a second time, I realized—with some amusement—that my “statues of ancient heroes” had a clear (but this time not literal) referent in the issue, on the pages immediately preceding the feature on therapsids. Since I hadn’t even been thinking about my dream at that point, I had simply missed it.

It was a feature with photos of a collector’s cramped dinosaur figurine collection, showing thousands of pale dinosaur models crammed together on shelves in a packed room of a house. I had not noticed the correspondence at first because my sublimely vast dream caverns were totally out of scale and proportion with this packed room, but the general sense was the same: “statues of ancient heroes” (many of them “lightly armored”) crammed together like in a multilayered storage facility. As I have described before, the exaggerated scale and importance of things in dreams often starkly contrast with the objective puniness or triviality of their precognitive or mnemonic referents in waking life.

It occurred to me to free-associate on the “archer” among my dream statues, and I immediately thought of one of my favorite Dunne dream examples from the published literature, a minor case that I had written about for Chapter 8 of my book: A patient of the psychoanalyst-parapsychologist Jule Eisenbud related to him a dream about being unable to hit a target with an arrow, and the next morning his favorite comic strip B.C. by Johnny Hart showed a character drawing a target around an arrow he had shot into a wall (above). It’s not the most amazing Dunne dream as Dunne dreams go (or the most hilarious comic strip), and for various reasons, Eisenbud didn’t even count it as a true precognitive dream. But because of it, these days, archery and arrows represent for me the issues of causation and retrocausation that I have been immersed in for the past few years while writing my book. Substituting a dinosaur model in the next issue of Prehistoric Times with an ancient hero drawing back his bowstring was a time gimmick a lot like the laser dot on the scutosaurus, or an archery dream precognizing a B.C. comic strip on the same topic.

It occurred to me to free-associate on the “archer” among my dream statues, and I immediately thought of one of my favorite Dunne dream examples from the published literature, a minor case that I had written about for Chapter 8 of my book: A patient of the psychoanalyst-parapsychologist Jule Eisenbud related to him a dream about being unable to hit a target with an arrow, and the next morning his favorite comic strip B.C. by Johnny Hart showed a character drawing a target around an arrow he had shot into a wall (above). It’s not the most amazing Dunne dream as Dunne dreams go (or the most hilarious comic strip), and for various reasons, Eisenbud didn’t even count it as a true precognitive dream. But because of it, these days, archery and arrows represent for me the issues of causation and retrocausation that I have been immersed in for the past few years while writing my book. Substituting a dinosaur model in the next issue of Prehistoric Times with an ancient hero drawing back his bowstring was a time gimmick a lot like the laser dot on the scutosaurus, or an archery dream precognizing a B.C. comic strip on the same topic.

I can’t emphasize enough: Discovering a past dream representation of yourself “looking back” at the dream later is a sublime, awe-inspiring experience. For me, it is the most powerful validation of precognitive dream interpretation as a gnosis: The knower is literally included in the known. It is also a startling confirmation of what Hermann Minkowski and Albert Einstein argued about the solid, block-like nature of spacetime: The past is still here, and the future is already here, we just usually lack eyes to see it. Again, such representations will be noticed more and more, the more you become attuned to precognitive dreaming.

O Attic Shape!

It can’t be stressed enough that a precognitive dream is not about “the future.” It is about a future experience in one’s life. But more than that, it is about the thoughts, feelings, and associations that will be provoked by that experience. This goes a long way toward explaining the interesting ways dreams deviate from the real-life experiences that precognitively catalyze them.

It is unusual in my experience for a dream image or scene to so literally pre-present a real scene or stimulus in my life as the “Permian battle” in my dream did. More often, dreams distort things in the manner of the “ancient heroes” in the subterranean gallery. They did not look like dinosaurs in the dream; the sense of them came through the verbal/symbolic register, a transposition that made sense only when the visual image (Greco-Roman military statuary) was translated into words: statues of ancient heroes. (Remember, it was reconnecting with the “heroes” of my childhood, dinosaurs, that prompted me to subscribe to Prehistoric Times in the first place.) This transposition into ancient human heroes facilitated the link to archery and the B.C. dream of Eisenbud’s patient, and via that to many associations from my book.

It connected, for instance, to the theme of Minkowski spacetime, where the past still exists. A vast (i.e., cosmic) storehouse packed with memorials, beings frozen in time, is a dream-representation of an idea that naturally comes to mind when I discover a dream was precognitive: a sense of awe at the “still-here-ness” of the past and the “already-here-ness” of the future. Among my other associations to the subterranean gallery full of marble ancient heroes was the confrontation between Perseus and Medusa in the original Clash of the Titans: Ray Harryhausen’s awesome animated Medusa slithers through her subterranean temple full of “statues,” which are really warriors that had been turned to stone by the Titan-archer’s terrible gaze.

It connected, for instance, to the theme of Minkowski spacetime, where the past still exists. A vast (i.e., cosmic) storehouse packed with memorials, beings frozen in time, is a dream-representation of an idea that naturally comes to mind when I discover a dream was precognitive: a sense of awe at the “still-here-ness” of the past and the “already-here-ness” of the future. Among my other associations to the subterranean gallery full of marble ancient heroes was the confrontation between Perseus and Medusa in the original Clash of the Titans: Ray Harryhausen’s awesome animated Medusa slithers through her subterranean temple full of “statues,” which are really warriors that had been turned to stone by the Titan-archer’s terrible gaze.

And I also thought of Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” a poetic image expressing the same basic idea, of stasis and eternity and permanence. When I looked up Keats’s poem, I found that “marble men” is an explicit image in its last stanza.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

Butch and Sundance

Eisenbud pointed out that his patient’s dream-choice of a B.C. comic for its precognitive target was itself a significant part of its meaning. I have found that precognition “likes” future stimuli having to do with juxtapositions of time. My two-part lucid dream about a dinosaur magazine is an obvious example. In early 2017, I wrote down the following dream that also exemplified the same principle:

Dream about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid—a long introduction to the movie that I had not seen before, in which Butch and Sundance are reunited at Union Station in Denver and warmly embrace, Sundance tells Butch he missed him, and then they kiss. The dream shifted and they were lying together in an MRI or CT scan tube, and I was a bit surprised that they had that technology back then. On a countertop were some modern medical supplies and some sort of salve or ointment from CVS.

My natural thought when I dream of a celebrity (or their character) is that they may have died; I have never once been right in this assumption, yet on a few occasions my research has turned up something else even more interesting. On the day after I had this dream, I did a Google search on Robert Redford, worrying that perhaps he had passed away and thus been “reunited” with his co-star Paul Newman. Instead, Google led me straight to an article about Redford’s warm, real-life friendship with Newman—something I may have been dimly aware of years ago but certainly had no reason to be thinking of at this point in my life. Among other things, Redford was quoted as saying how much he missed Newman. That article, however, led to an even more interesting Esquire piece about Redford’s career and his early, unfair treatment by the critic Pauline Kael. There, I came across a striking passage about Kael’s “savaging of The Sting, the reunion of Redford and Newman and [director] George Roy Hill.” Kael’s review of the movie is quoted in the very next sentence: “I would much rather see a picture about two homosexual men in love than see two romantic actors going through a routine whose point is that they’re so adorably, smiley butch that they can pretend to be in love and it’s all innocent.”

My natural thought when I dream of a celebrity (or their character) is that they may have died; I have never once been right in this assumption, yet on a few occasions my research has turned up something else even more interesting. On the day after I had this dream, I did a Google search on Robert Redford, worrying that perhaps he had passed away and thus been “reunited” with his co-star Paul Newman. Instead, Google led me straight to an article about Redford’s warm, real-life friendship with Newman—something I may have been dimly aware of years ago but certainly had no reason to be thinking of at this point in my life. Among other things, Redford was quoted as saying how much he missed Newman. That article, however, led to an even more interesting Esquire piece about Redford’s career and his early, unfair treatment by the critic Pauline Kael. There, I came across a striking passage about Kael’s “savaging of The Sting, the reunion of Redford and Newman and [director] George Roy Hill.” Kael’s review of the movie is quoted in the very next sentence: “I would much rather see a picture about two homosexual men in love than see two romantic actors going through a routine whose point is that they’re so adorably, smiley butch that they can pretend to be in love and it’s all innocent.”

My dream seemed to have been pre-inspired by this passage suggesting a homoerotic “reunion” of Butch and Sundance.** Per standard dream overdetermination, the dream doubly represented the idea of a reunion by setting the dream kiss of Butch and Sundance at “Union Station,” a place familiar from my childhood. The CVS ointment or salve on the counter points associatively to the idea of an insect bite or sting. My dreaming brain’s placing of these characters in a modern CT scanner (and feeling “surprised they had the technology back then”) was another time gimmick, pre-presenting my own internet scrutiny of Redford and Newman’s relationship after the dream, and my dreaming brain’s confused juxtaposition of the computer-mediated nature of that “scan” and the sepia-toned setting of those period movies starring the real-life actor buddies.

In other words, the anachronism of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid itself—a distinctly modern-feeling buddy comedy (with late-1960s Burt Bacharach score, etc.) set the better part of a century earlier (and I might add, one of my all time favorite films)—was itself folded into its precognitive significance. Anachronisms of one sort or another act as “attractors” for the precognitive brain.

Postscript: All Ye Need to Know

Another magazine I subscribe to, and also avidly read (although not to my two-year-old), is New Scientist. In a recent (July 14-20, 2018) issue, one of its editors, Rowan Hooper, penned a “Field Notes” piece about his visit to the 35th annual International Dream Conference in Phoenix. He visited the “interdisciplinary” (his scare quotes) conference to learn about the latest in scientific psychology and neuroscience of dreaming but found himself in a disturbingly mixed (one might even say interdisciplinary) group that included New Agers, psychoanalysts, and (shudder) parapsychologists expressing a profoundly distressing panoply of beliefs about dreams—such as that they may foretell future events. Having lunch with a psychoanalyst who believes dreams can be precognitive, he writes, he nearly choked on his burrito. Many people at that meeting, he lamented, expressed their belief in precognitive dreams.

“Our fascination with dreams goes back millennia, with many ancient cultures believing they carried messages from spirits or spoke to us of the future,” Hooper writes. “How sad that thousands of years later, we are still bogged down in such mysticism, when we could instead be probing what truly generates dreams, and what they tell us about consciousness and how our brains work.”

In other words, despite the famous mystery, even to scientists, of dreams and dreaming, this editor clearly went in “knowing all he needed to know” about dreams: they’re not “mystical”; they don’t speak of the future, etc. He wanted to see a homogeneous set of scientists upholding that narrowly materialistic (in the bad sense) viewpoint. “Call me naïve,” Hooper writes, “but it was a shame to find an ‘us versus them’ attitude among the non-scientists.” The psychoanalyst he had lunch with would call that projection, since Hooper himself clearly took such an attitude toward those non- or para-scientific ‘others’ and their “mumbo jumbo.” Who is the “us” and who the “them,” exactly?

Lest any New Scientist readers be on the fence about the possibilities of precognitive dreaming, Hooper provides the standard explaining-away: “No matter that with so many people dreaming each night, this is quite likely to happen by chance.” But the law of large numbers argument skeptics like Hooper always rest their cases on depends on the phenomenon in question happening rarely. In fact, those who have followed in the footsteps of J. W. Dunne and investigated their own dreams for evidence of precognitive material often come away with substantial evidence that precognitive dreams are the norm. When people can show from their own dream databases that precognitive dreams are common, even nightly occurrences (see for instance Bruce Siegel’s excellent Dreaming the Future, or Andrew Paquette’s Dreamer), then the law of large numbers argument flies straight out the window.

Lots of alleged precognitive dreams, because their relationship to a putative target consists of highly personal associations, understandably hold little weight with skeptics, who are as hostile to psychoanalytic premises as they are to parapsychological ones. If I were to relate the “statues of ancient heroes” dream episode to someone like Hooper and show him the magazine spread I alleged it precognized, he would no doubt roll his eyes. I wouldn’t really blame him. And if I related a dream like the one about Butch and Sundance, he would quite reasonably counter that if I looked long and hard enough in an Internet search about any famous person, I would eventually find some piece of text that might seem to match my dream. Fair enough. (It’s sort of the “put 20 monkeys in a room with typewriters and you’ll eventually get Hamlet” principle.)

But if I really wanted to make Hooper choke on his burrito, I would relate the “Permian battle” dream and ask how coincidence could in any way, shape, or form explain its exact correspondence to a picture in a magazine I received in the mail the next day.

Despite my love of prehistoric animals, I never dream about them. I have on a few occasions in roughly a quarter century of keeping an electronic dream diary dreamed about trilobite-like, vaguely prehistoric sea invertebrates; and dinosaur-related books or films have appeared in a few dreams in my journals, but the number of times dinosaurs, dinosaur fossils, or similarly charismatic extinct creatures have appeared in my dreams can be counted on the fingers of one hand. And I have never in my life dreamed about Permian fauna. Again, this is in 25 years of (mostly faithfully) recording my dreams.

Despite my love of prehistoric animals, I never dream about them. I have on a few occasions in roughly a quarter century of keeping an electronic dream diary dreamed about trilobite-like, vaguely prehistoric sea invertebrates; and dinosaur-related books or films have appeared in a few dreams in my journals, but the number of times dinosaurs, dinosaur fossils, or similarly charismatic extinct creatures have appeared in my dreams can be counted on the fingers of one hand. And I have never in my life dreamed about Permian fauna. Again, this is in 25 years of (mostly faithfully) recording my dreams.

I knew practically nothing about Permian land carnivores before this dream; I did not know what they were called; and I did not know they were going to be featured in the Winter 2018 issue of Prehistoric Times. The previous issue of the magazine (I quickly verified) contained no “In the Next Issue …” teaser—not that I would have known what “therapsids” referred to in any case. I had basically forgotten about my subscription by the time this issue arrived, so its arrival was a total surprise. There is simply no way my dream about a scutosaurus fighting with a sauroctonus on the morning before getting the magazine featuring these obscure creatures was coincidental. And the fact that I wrote the dream down beforehand rules out retroactive memory distortion. More to the point, though, the correspondence, even if it was uniquely vivid, fits a very common, widely replicated pattern, undercutting the notion that it must be seen as a rare one-off (and thus “likely to happen by chance”).

Debates between psi-believers and skeptics are a lot like Keats’ Grecian Urn: Attic figures frozen in time, locked in an eternal dispute that goes nowhere. Meaning-centered phenomena resist purely scientific approaches, and this has put the study of dreams (like the study of psi) at an impasse for decades. Ever wonder why every popular science piece proclaiming the answer to why we dream (“it’s nocturnal therapy,” “it prepares us for threats,” and so on) sounds vaguely unconvincing and then is replaced by a completely new answer a few months later? It’s an argument why the humanities need to be brought into the dialogue with sleep scientists, to move things forward. That’s right, interdisciplinarity, one of the things I make a case for in my book.

The “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” thing, also, needs to be re-thought. It is really just a paradigm buttress, and an excuse to avoid dealing with threatening data, by moving the goalposts. No one with access to research dollars is going to jeopardize their career by studying the question of dream precognition in a way that might produce “extraordinary” evidence. This effectively exiles the whole topic to the disreputable zone of anecdote or, at best, small studies in parapsychology journals that mainstream scientists readily ignore. Hooper writes that his head was in his hands by the end of a keynote address by Stanley Krippner, who conducted what are still the best-known dream-ESP studies a half century ago; but they were tiny studies and thus hold zero scientific weight in the world of big-budget science Hooper is used to.

Around the question of precognition and precognitive dreams, I think “extraordinary claims” should be turned around: What is really so extraordinary about dreams providing a glimpse of the future? Could the fact that people for thousands of years have believed, even assumed, this was the case be a clue worth at least taking seriously? Collective skepticism around precognition can be shown to be rooted in historical-social convention and taboo, not reason or even evidence. Physics allows information to reflux from the future. Quantum computers can scramble causal order (as you can even read in New Scientist), and a kind of computation across time may even be what gives them their power. And guess what pinkish-gray squishy organ is increasingly thought, by serious scientists, to be a quantum computer?

Once the larger paradigms (in physics and biology) shift, psychology and other fields will eventually be forced to follow. Rather than further belaboring the case for precognition to anxious, cognitive-dissonance-fearing audiences who won’t listen anyway, I think our time is best spent working out its mechanisms and its implications … as I do in Time Loops (available from an internet mega-retailer near you).

NOTES

* Not accidentally, a literary example that was also fresh in my mind at that point, because of my book, was the story “A Sound of Thunder,” by Ray Bradbury. It is about time-traveling hunters who travel to the Cretaceous period to bag a T-Rex but find upon their return that one of them had, by stepping off an assigned path, crushed a butterfly in the distant past, and thereby altered the course of history.

** Another common experience in the precognitive-dreamwork path is doing research in a book or online, spurred by a dream, and coming across a piece of text or a picture that is clearly the precognitive “source” of the dream. Phil Dick recorded several examples of this time-looping logic in his letters, for instance, and the dream about Butch and Sundance is just one of several examples of this phenomenon in my own experience.

I can certainly relate to your experiences Eric. I’ve had many of those wow moments, usually the following day or two after a vivid dream.

For me, people, places and things which are connected to a heightened emotional feeling may rise to some kind of tipping point, and are reflected back to my dream life. A state of no time. Is deja vu simply a memory of a precognitive dream, triggered by the person, place or thing you are currently experiencing?

Looking forward to getting your book.

Greg