Wormholes, Freud, and Jacob the Dreamer

In the 1980s, when the possibility of wormholes began to capture physicists’ imaginations, there was the inevitable concern about what such objects might mean for causality in an Einsteinian, time-elastic universe. Wormholes through space meant, inevitably, wormholes through time. And so, naturally, people thought of the grandfather paradox, that strange fantasy of killing one’s patriarchs that is the big stumblingstone for rational people when trying to countenance the idea of time travel. Killing one’s grandfather or (Oedipally) one’s father, though, boils down to a fantasy of self-negation; so, when physicists model this problem, it is more convenient to cut out the patriarchal middlemen and ask about the neurotic possibility of self-inhibition or (more extremely) suicide in time-traveling objects.

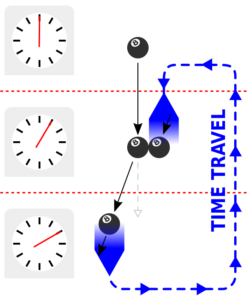

In the early 1980s, a Russian physicist named Igor Novikov worked out that physical law would actually prevent any such self-inhibition, that in fact a principle of self-consistency would govern a wormhole-riddled universe. Even if an object could enter a wormhole at some time point B and emerge earlier, at some time point A, it could never actually interfere with its own entry into the wormhole at that later time point B. Two Caltech students of black hole and wormhole expert Kip Thorne checked and found that Novikov was right: First, a time-traveling billiard ball cannot take the place of its younger self—a kind of “exclusion principle” would prevent that (more on which in a future post). Instead, what happens is the time-traveling object encounters its earlier self and interferes in such a way that its later entry into the wormhole is actually facilitated.

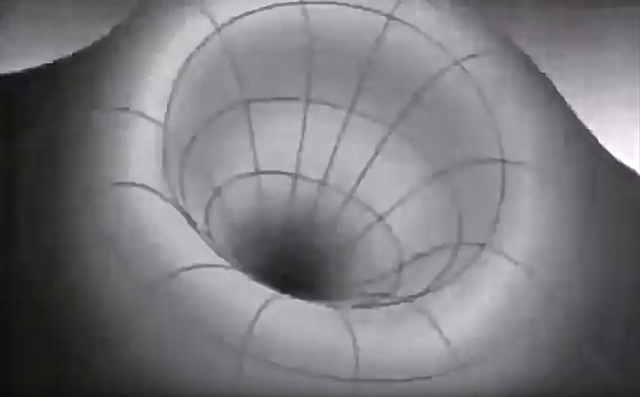

All possible paths of a billiard ball entering a wormhole later (bottom, in graphic at right) would in fact, upon exiting the wormhole earlier (top), nudge itself into the mouth of the wormhole later, thus completing the causal tautology, or what physicists call the closed-timelike curve. These days, quantum physicists use the idiom of “post-selection”—a kind of informational-causal Darwinism which ensures that the only information that survives its journey into the past is information that does not foreclose its origins in the future.

All possible paths of a billiard ball entering a wormhole later (bottom, in graphic at right) would in fact, upon exiting the wormhole earlier (top), nudge itself into the mouth of the wormhole later, thus completing the causal tautology, or what physicists call the closed-timelike curve. These days, quantum physicists use the idiom of “post-selection”—a kind of informational-causal Darwinism which ensures that the only information that survives its journey into the past is information that does not foreclose its origins in the future.

My book Time Loops touches lightly on the physics of time-traveling billiard balls and quantum informational reflux into the past, but it delves mainly into the psychodynamic principles governing time-traveling information in our tesseract brains. It is no coincidence, I think, that the associative laws of the unconscious work so nicely to prevent paradox in beings who are subject much more than we know to premonitions and who are constantly guided by a kind of presentimental orientation toward future rewards. The unconscious, I suggest, is just ordinary conscious thought displaced in time. Paradox is prevented by the very nature of the rules that allow information to reflux into the past, specifically the limitations on making that refluxing information meaningful as opposed to noise.

Dreams offer the best example for what I’m talking about. A typical precognitive dream is an oblique and indirect associative halo around some future experience or train of thought; its exact relationship to that experience or train of thought only becomes clear in hindsight. There are apparent exceptions: more obvious premonitions that may even be almost “video-quality” in their transmission backward of some future scene (I believe this is exactly what sleep-paralysis episodes and “out of body experiences” may in fact be*); but even in those cases, the “metadata” of the transmission is always lacking: the when, where, and how, as well as the meaning, or how the event fits into the ordinary course of life. One way or another, the information that arrives from the future in dreams and altered states is garbled or incomplete and thus cannot be used to foreclose the inciting experience.

Could the laws preventing billiard balls from interfering with themselves in wormholes offer us a new way of thinking about the processes of distortion in dreams?

Irma’s Injection

The mechanisms that control the back-flow of information in the tesseract brain are probably not as picturesque as spacetime-bending wormholes—I suggest they probably will turn out to have something to do with quantum computation controlling brain plasticity (the constantly updated strengths of neural connections). But whatever the ultimate explanation, the principles are similar: Our future conscious thoughts interfere with us in the present and deflect us just the right way so we end up having those future thoughts at just the right time, creating time loops in our lives.

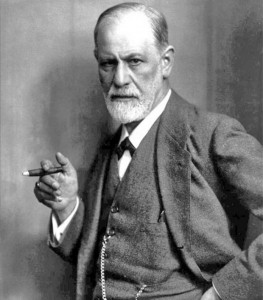

The best example of this happens, not coincidentally, to be one of the most famous and influential dreams in history: Freud’s “specimen dream” about “Irma’s Injection” in Chapter II of The Interpretation of Dreams. I discuss this dream at length in my book, but the short version is this: In 1895, Freud dreamed he was examining a patient and childhood friend of his, Anna Hammerschlag, whom he gave the name “Irma” to protect her anonymity. In real life, Anna’s problems were purely psychological (“hysteria”), but when Freud’s dream-self looked inside her mouth, he saw a white patch and scabs on her cheek and palate and a feature that should only have been visible in the nose. It was hard to get her to open her mouth—she acted like a woman shy because of wearing dentures. He summons a trio of physician friends to have a look—they poke and prod and pompously mansplain, like stereotypical Victorian doctors—and lastly Freud’s dream-self concludes that what caused Irma’s oral malady was an injection administered thoughtlessly, with a dirty syringe, by one of those friends, his family pediatrician, whom he gave the pseudonym “Otto.”

The best example of this happens, not coincidentally, to be one of the most famous and influential dreams in history: Freud’s “specimen dream” about “Irma’s Injection” in Chapter II of The Interpretation of Dreams. I discuss this dream at length in my book, but the short version is this: In 1895, Freud dreamed he was examining a patient and childhood friend of his, Anna Hammerschlag, whom he gave the name “Irma” to protect her anonymity. In real life, Anna’s problems were purely psychological (“hysteria”), but when Freud’s dream-self looked inside her mouth, he saw a white patch and scabs on her cheek and palate and a feature that should only have been visible in the nose. It was hard to get her to open her mouth—she acted like a woman shy because of wearing dentures. He summons a trio of physician friends to have a look—they poke and prod and pompously mansplain, like stereotypical Victorian doctors—and lastly Freud’s dream-self concludes that what caused Irma’s oral malady was an injection administered thoughtlessly, with a dirty syringe, by one of those friends, his family pediatrician, whom he gave the pseudonym “Otto.”

After free-associating on this dream’s various elements, Freud concluded that the “latent dream thought” embedded in this tableau was a wish that he be innocent of any failures or malpractice in his treatment of Anna (malpractice was going around in his medical circle at the time) and that Otto instead be the one at fault for the fact that, in real life, his friend Anna had not improved despite his psychoanalytic treatment. It was this dream that led Freud to the famous, controversial conclusion that all dreams are the disguised fulfillment of repressed wishes.

In 1982, a Brazilian psychoanalyst and cancer surgeon named Jose Schavelzon noticed something amazing: The precise symptoms displayed in dream Irma’s mouth matched the progression of oral cancer that Freud himself suffered nearly 3 decades later: a white patch, followed by scabs in the aftermath of increasingly invasive surgeries and radiation treatments; surgeons had to remove part of his jaw and palate, which exposed his nasal cavity to view inside his mouth—it would have exposed precisely the feature he thought he could see in “Irma’s” mouth. It became hard for Freud to open his mouth once a denture-like prosthetic was fitted, and he could only barely talk for the last decade and half of his life. The “Irma dream” seems, in other words, like a premonitory dream about the grave illness that severely impeded Freud’s quality of life in his old age.

The premonitory nature of this dream has been discussed by other writers such as Robert Moss and Larry Dossey, but I think we should go farther: This dream needs to be re-read as representing/dramatizing a set of conscious thoughts (and wishes) Freud would have had in 1923, following his cancer surgeries, rather than “unconscious” wishes belonging to the year 1865 when he had the dream.

When bad things happen to good people, even good people may find themselves wishing the bad thing had happened to someone else. We have no proof, obviously, but Freud’s thoughts in 1923 and later may well have included a vague wish that someone else and not him might suffer the awful cancer and brutal surgeries he was enduring. In any case, we can be quite confident that his thoughts at this point in his life would certainly have included a self-reproach for not following the urging of his best friend Wilhelm Fliess (another in that physician trio), who in 1895 had been trying get him to quit smoking his cigars for the sake of his health. In fact, Freud had just relapsed from a short period of abstinence just before having the dream and was specifically worried what his friend would say—this may have even sparked the temporal “short circuit” with his later situation. That situation was caused, one will note, by something symbolically very like a “dirty syringe.” Freud’s dream-self reproaches his patient “Irma” with the very words he might have consciously directed at himself: “You know, it’s really only your own fault.”

Most importantly, I argue, Freud could not have been blind, in 1923, to the similarity between what was happening in his own body then and the symptoms Irma had displayed in the dream 28 years earlier that wound up putting him on the scientific map. Thus, his thoughts would have returned to that dream and included a wish that he had been correct that dreams (especially that one fateful dream) are really “just” wish-fulfillments and not premonitions of future events. That dreams could predict the future was a common folkloric belief that, throughout his career, he took every opportunity to disclaim and debunk, but how could this coincidence not have unsettled that outward certainty? Wishing he was right about dreams being just wishes would effectively wish away his cancer as well as put himself above any professional reproach for having misled the world about the meaning of our dreams.

It is precisely the kind of situation Freud found himself in in following 1923—surviving, but at a cost—that precognitive experiences typically focus on. Dreams seem to navigate us through perilous shoals in life, ironic and unsettling ordeals (usually much more minor ones) where we come out the other end changed and, typically, humbled.

Psychic 8-Ball

How do wormholes fit in to all this? Remember that time-traveling billiard ball, deflecting the path of its earlier self so that it nudges itself into the wormhole, completing the loop. Freud noted that dreams commonly saddle others with our own unwanted predicaments and “give” thoughts we don’t want to acknowledge having to other people in our lives. This fact has been noted again and again in other dream theories, but Freud’s theory explicitly framed it in terms of “defense mechanisms” such as projection and displacement. The unacceptable thought struggling to be expressed is deformed and sent off course by a kind of “psychic” (in the older sense of the term) force field, a kind of deflection.

By the laws of self-consistency and post-selection, Freud’s dreaming brain saw fit to deflect his symptoms onto someone close enough to him to be highly salient. (In Time Loops, I discuss various reasons why his friend Anna Hammerschlag fit the bill), but in such a way that its premonitory nature would not and could not have occurred to him … until it was too late. One of Freud’s biographers noted that various other maladies of dream Irma and discussed by the physician trio were actually Freud’s own illnesses at the time he had his dream—rheumatism, intestinal issues, etc.—so their inclusion in a bundle with his later cancer makes perfect sense.

By the laws of self-consistency and post-selection, Freud’s dreaming brain saw fit to deflect his symptoms onto someone close enough to him to be highly salient. (In Time Loops, I discuss various reasons why his friend Anna Hammerschlag fit the bill), but in such a way that its premonitory nature would not and could not have occurred to him … until it was too late. One of Freud’s biographers noted that various other maladies of dream Irma and discussed by the physician trio were actually Freud’s own illnesses at the time he had his dream—rheumatism, intestinal issues, etc.—so their inclusion in a bundle with his later cancer makes perfect sense.

In short: Freud’s most famous dream was like a billiard ball sent back to his younger self by his 68-year-old brain. The big 8-ball in his life that deflected him onto being the great pioneer of the new method called psychoanalysis was itself a wish from his future self that he’d done a few things different when he was younger, including being less adamant that dreams were only disguised fulfilments of repressed wishes. It was a corner he could not back himself out of. This is why I say that it was “not coincidental” that his most famous and significant dream happened to center on the most grave circumstance of his later life: It had to be a particularly powerful and significant shot to deflect him in just the right direction, that many years before.

There are many other looping dimensions to this dream—it’s a veritable temporal-biographic clusterfuck, and you’ll need to read Chapter 9 of my book for all the amazing details. And it couldn’t really have been clearer than it was. Freud could not have had a crystal-clear (or video-quality) premonition of his own cancer that terrified him into quitting smoking, because then he wouldn’t have gotten cancer, and thus wouldn’t have had the dream. His dream, and in some sense his whole career—indeed his “immortality”—depended on that outcome, and the specific ways in which he misinterpreted it from his younger vantage point.

A principle could be formulated here: Our blindness to our precognitive nature is what leads us to having the experiences our dreams precognize. There are still many open questions: Is it the message itself that is distorted in its backward temporal passage, or is it our conscious interpretation of those pieces of mail from our future self that distorts their message? In other words, is the dream itself a misinterpretation of a clear retrograde signal or is the signal itself distorted in its backward passage, or both?

Jacob’s Bum Hip

In artistic and critical contexts, the defense mechanisms that protect the ego by deforming our thoughts and actions are sometimes called tropes, “turnings,” or what Harold Bloom calls swerves. These are good terms: Instead of having a dangerous realization, our thoughts deviate onto a safer path, and we only feel a troubling anxiety, like our hair standing on end from a nearby electric field. It is not an accident that Freud’s famous time-traveling archetype Oedipus walked with a limp—in fact, it’s the etymological meaning of his name (“swollen foot”). Like a shopping cart with one stuck wheel, the dreaming self swerves in its avoidance of thoughts that will cause trouble (thoughts like Freud’s famous “wanting to sleep with your mother”). On its own, the mind wants to go in circles of rationalization and denial rather than press forward into uncharted and dangerous territory. This is the repetitive, “orbiting” behavior of the neurotic symptom.

It so happens that one of the most famous Biblical dreamers, Jacob, also swerved, because of a dream. I’m not referring to his famous dream of angels ascending and descending a ladder to heaven. The more decisive episode in this trickster-shaman’s life is his all-night wrestling match on his return trip from Canaan, with a shadowy, silent figure on the banks of the river Jabbok.

The same night he arose and … crossed the ford of the Jabbok. … And a man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day. When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he touched his hip socket, and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, “Let me go, for the day has broken.” But Jacob said, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” And he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob.” Then he said, “Your name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed.”

Rule #1 of myth interpretation is that any ordeal that “lasts all night” and ends with the sunrise is referring to a dream. Jacob encountered and struggled with what he thought was God in his dream. Was it God or was it his own future self? Could the former not be our misrecognition of the latter? Philip K. Dick suggested this, and so did precognitive-dream pioneer J. W. Dunne, for whom our dreaming higher consciousness was equivalent to the God of the mystics. Whoever Jacob wrestled with, it left him with a limp.

Rule #1 of myth interpretation is that any ordeal that “lasts all night” and ends with the sunrise is referring to a dream. Jacob encountered and struggled with what he thought was God in his dream. Was it God or was it his own future self? Could the former not be our misrecognition of the latter? Philip K. Dick suggested this, and so did precognitive-dream pioneer J. W. Dunne, for whom our dreaming higher consciousness was equivalent to the God of the mystics. Whoever Jacob wrestled with, it left him with a limp.

Again, it may be that we misrecognize our own future experiences and thoughts and wishes in our dreams, and thus take oblique and even mildly self-destructive paths in our lives, precisely to the extent that we cannot recognize ourselves in them and still remain self-consistent. Moreover, our swerves to avoid self-recognition, the defense mechanisms that distort our reasoning (the debased modern word, infected with an arrogant scientism, is “bias”) may be the more extreme the more our fate is spectacular. The patriarch Jacob’s fate was highly significant—he assumed the name “Israel” after this dream, after all—and his displacement by his backward-traveling-billiard-ball future self felt like no less than a struggle with the Creator. Freud’s fate was spectacular too—I would argue, deservedly so, despite many missteps and mistakes along his path—and his defensive swerving was also spectacular and multidimensional, as I show in my book. But we all have it in us to be pioneers in exploring and laying claim to our own country. We all have it in us to be Jacobs.

How do you claim ownership of your life? Go back to your dreams, the ones you have never forgotten and may even have written down, yet naturally imagine could not have any relevance to little you, right now, today. I have found not only in my study of famous writers’ dreams but also in my own humble dream life that the “biggest” dreams, the ones that might even have inspired us in a decisive course of action or study, often reach across years of our lives; they were big precisely because they have to do with the ways we return to them or reflect on them much later. Your initially unrecognized reflection may seem especially huge and symbolically complex in an old dream, like looking at yourself in a parabolic mirror.

Look at your old dreams again with new, Freudian eyes, but leave aside Freud’s defensive admonition that dreams never show us our future. He was right about their characteristic swerves, but he was wrong in denying their time-defying character.

The Question

The reality of precognition in our lives (a constant reality, I argue, to which occasionally noticed precognitive dreams gives just a taste) offers a totally new way of looking at the basic question Freud posed most clearly for our time: Why do we know ourselves so poorly? What accounts for the vastness of our un-conscious? If we are getting glimpses of our future, shouldn’t we know ourselves better?

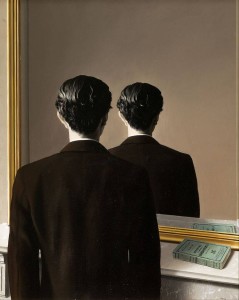

Maybe the whole question of self-knowing is wrong, or wrongly posed. Freud operated within the classical assumption of the mind as a mirror of the world. It goes by many names—representationalism, for one—but the basic assumption was that ideally the mind should reflect reality, including the pre-existing reality of who we ourselves are. To explain our foibles and irrationality, Freud appealed to our baser instincts and desires that were incompatible with our socialized egos. In our repression of facts we don’t want to face about ourselves, we distort that mirror … and it ends up distorting everything else along with it.

Maybe the whole question of self-knowing is wrong, or wrongly posed. Freud operated within the classical assumption of the mind as a mirror of the world. It goes by many names—representationalism, for one—but the basic assumption was that ideally the mind should reflect reality, including the pre-existing reality of who we ourselves are. To explain our foibles and irrationality, Freud appealed to our baser instincts and desires that were incompatible with our socialized egos. In our repression of facts we don’t want to face about ourselves, we distort that mirror … and it ends up distorting everything else along with it.

But as Richard Rorty argued in his now-classic Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (in a perhaps unconscious transmission of the sixth Zen patriarch Hui-Neng, whose two-word version was “What mirror?”), maybe that mirror itself is the problem. Modeling knowing on the eye and what it apprehends led to many unproductive assumptions about the mind, including the idea that there is some knowable essence that we get wrong, or misrepresent, and thus that there is a truth lying behind these distorted appearances. Rorty, a pragmatist-deconstructionist, sees this all as a kind of smokescreen distracting us from grasping thinking as something we do, with other people (an extension of communicating). One of the things we do, I would add, is discover ourselves, discover who we are, at every moment. And as I argued in my last post (and in Time Loops), what if that discovering is simultaneously our own making, in our past?

What if there’s no “truth” about ourselves, precisely because we always arrive at a truth that is its own making? What if our entire substance is swerves (or loops)?

What Freud called the unconscious is really that portion of our consciousness (or our cognition) that happens in our future, and that inflects our actions and bends our interpretations in the present (including future memories, future discoveries about the moment we are living through right now). At every moment, we are Jacob on the shore of the Jabbok, wrestling with a presence that is unrecognized and unknown—our own future self. In Interstellar, “Coop’s” future self tries to warn his younger self against going on a mission that involves traveling through a wormhole, but obviously that won’t work. What happens instead is that his messages are understood from the wrong point of view, the point of view of his ignorant younger self. He is the billiard ball that deflects a younger version of himself into the wormhole, quite literally.

This is our predicament: We are always ignorant of the future that is inflecting us. The only times we aren’t is when that future is unavoidable.

When we see our behavior at every moment as a compromise our outcome of efficient causes “pushing” from our past and refluxing thoughts from our future deflecting or swerving us, we see ourselves in a different light, and even may get a new, philosophical distance on age-old, unproductive hangups like whether or not we possess free will. In the Glass Block Universe, our field of “freedom” is not our future; it is our self-creation in and of our own past, the simultaneous discovery and creation of who we always were.

NOTES

* Episodes of sleep paralysis, I have come to suspect strongly (as a lifetime sufferer), are lucid dreams in which you vividly and realistically precognize being awake in bed a few minutes later. You may see your surroundings just as they are in real life, as though your eyes are open, but in fact, those experienced with sleep paralysis may note that in fact their eyes are not open even though they seem to see their room, etc.—hence the incorrect belief that you are awake and paralyzed, rather than still sleeping but lucidly precognizing a future awake situation. You feel frustrated and terrified at your inability to move, and the confused sleeping brain may interpret this as a malevolent possession or inhibition (e.g., being sat on by an “old hag” in some folkloric contexts). My hunch is that the intense terror arises from the semi-lucid brain’s maddening inability to control the body from a temporal vantage point in the visual stimulus’s past.

––There are still many open questions: Is it the message itself that is distorted in its backward temporal passage, or is it our conscious interpretation of those pieces of mail from our future self that distorts their message? In other words, is the dream itself a misinterpretation of a clear retrograde signal or is the signal itself distorted in its backward passage, or both?––

What if there is no backwards temporal passage, but an unpacking of the now instead?

You’re tapping into really difficult terrain with the science part of your book. It’s not easy to have a well-reasoned, thought-through opinion on the block universe and its implications, or on the plausibility of retrocausation in quantum physics. For non-experts that requires lots of additional reading, and the experts themselves are in constant debate about everything.

Personally I am having troubles to see the connection between the block universe and retrocausation. If we are living in a block universe, and you repeatedly make that case, than there’s no need for retrocausation.

All the spaghettis in the block are already transformed back to the start by all their future interactions. And if a spaghetti already contains all its future states, there can be no retrocausation of any kind. There is nothing to come from the future, no influx of information, and thus no need for post-selection either. If the universe is fixed there is no way of avoiding trauma or of enhancing outcomes. Everything is already there.

From this point of view there is no need for precognitive reward circuits, or for a censor mechanism that prevents paradox, or for stock market future detectors.

So how do the block universe and retrocausation get along? Or in different terms, what is the connection between tenseless time and tensed time? Any thoughts or hints? I know all this physics stuff is optional, so don’t get yourself into to much trouble regarding this question.

Thanks!

HP