Where Was It Before the Dream? — Time Loops and Creativity

Dreams go hand in hand with origins, so it is conveniently coincidental—coincidentally fractal maybe—that what is usually considered to be the first recorded poem in our tongue was about the origins of origins—the beginning of created things—and was composed in a dream after the poet had tried to escape the burden of being original himself.

Caedmon was an aging, illiterate cow-herder for the Abbey of Whitby in the Kingdom of Northumbria in the late 600s of the Common Era. We would now say he had a terrible fear of public speaking. Whenever the harp was being passed around the hall for everyone to take their turn, he would slip out into the night to avoid the humiliation of having nothing to sing.

According to Bede, the great historian of this period, one night after the old introvert had fled the pressures of the hall, he fell asleep in the byre near the cows it was his job to watch, and he was approached in a dream by a man who bade him to sing. Complaining that he could not sing, the dream-figure told him to sing “about the beginning of created things.” Suddenly, in his dream, Caedmon found himself singing the following, beautifully composed lines in praise of “the work of the father of glory”:

According to Bede, the great historian of this period, one night after the old introvert had fled the pressures of the hall, he fell asleep in the byre near the cows it was his job to watch, and he was approached in a dream by a man who bade him to sing. Complaining that he could not sing, the dream-figure told him to sing “about the beginning of created things.” Suddenly, in his dream, Caedmon found himself singing the following, beautifully composed lines in praise of “the work of the father of glory”:

Now [we] must honour the guardian of heaven,

the might of the architect, and his purpose,

the work of the father of glory

as he, the eternal lord, established the beginning of wonders;

he first created for the children of men

heaven as a roof, the holy creator

Then the guardian of mankind,

the eternal lord, afterwards appointed the Middle Earth,

the lands for men, the Lord almighty.

When the cowherd-dreamer brought his verse to the Abbey’s clerics, he was sent to the Abbess herself, Hild (later St. Hilda), who recognized in his composition the work of divine inspiration and persuaded him to take up the monk’s habit. Bede tells us that Caedmon spent the rest of his days transforming sacred history, as told to him by his fellow monks, into beautiful songs. Unfortunately, the only work that has survived is his first, 9-line hymn of praise to the Creator, “received” in a dream. (There’s a nice exegesis of the hymn here.)

Way too many centuries have elapsed to put all that much evidential stock in Bede’s account of Caedmon and his inspired song.* But his narrative stands at the beginning of a long line of stories about poems, novels, and other artworks whose genesis supposedly came to the artist in a dream or in some hypnagogic or hypnapompic, semi-awake state.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge reported getting his very best poem, “Kubla Khan,” in an opium-induced dream. Mary Shelley—given permission by Coleridge—reported getting the idea for Frankenstein from a hypnopompic reverie. Robert Louis Stevenson got the plots of some of his stories, including Dr. Jekyll and Mister Hyde, from dreams. Franz Kafka wrote many of his stories, such as “The Metamorphosis,” after significant images came to him during or following a dream. J. R. R. Tolkien wrote his elvish mythologies from a trancelike semi-dream-state he called “faerie.” Salvador Dali used the hypnagogic state to get ideas for his paintings. And it’s just as true of scientific explorers. No book or article on the subject of creativity fails to mention August Kekule, who claims to have discovered the ring-structure of benzene from a hypnagogic vision of snakes eating their own tails.

Critics and biographers love debunking these stories. They will point out, as they have done ad nauseam in Coleridge’s case for example, that saying “it came to me in a dream” is a handy way of excusing the flaws of a work, or perhaps its brevity (as with the short “Kubla Khan”). It also creates a handy excuse for cultural borrowings, or intellectual property theft. Kekule only told the story of the dream-origins of “his” benzene discovery at a fest in his honor decades later, when some of the scientists in the audience may have been aware that at least two other researchers had published on benzene’s ring structure before Kekule ever did. Saying “it came in a dream” and that he waited a few years before publishing on it (just to be sure the dream was right) seems to have been Kekule’s way of justifying the glory being bestowed upon him in the face of others’ (and his own) doubts as to his originality.

But treating dreams and reveries as a rhetorical fig leaf does not negate the reality of the phenomenon of ideas coming in these daily altered states. It’s a real thing. Anyone who dreams and creates in some fashion, whether via writing or in any other medium, or even science, knows how fertile the unconscious is, and how normal it is to wake up with the feeling of having glimpsed some wondrous idea only to have it fade like the morning dew. Occasionally writers and artists do manage to capture a bit of that magic, and turn it into art or some new scientific discovery or invention.

The question that hovers over these narratives, though, is: But where was it before the dream?

No Sweat

When you drill down into your theory of creativity and even causality more generally, there’s the problem of making the new from the old. The question of origins in the realm of culture has direct analogues in natural history and cosmology. If things tend to repeat—natural processes, the forms of living things, cultural memes—what is the source of new things under the sun? How do you get life from lifeless chemistry, new species from old ones, and unheard-of ideas?

God’s creative Act at the beginning of Genesis has provided a convenient model for writers and artists through the ages when thinking about their own creative process. Caedmon would not have doubted the divine origins of his hymn. But most in our day are not satisfied appealing to gods (or spirits) when some more mundane explanation is imaginable. God’s solution—creating from nothing—is truly Herculean … and we assume, impossible. We frame the problem instead as the reshaping of some raw material that’s already present in the world, including the raw material of pre-existing ideas.

God’s creative Act at the beginning of Genesis has provided a convenient model for writers and artists through the ages when thinking about their own creative process. Caedmon would not have doubted the divine origins of his hymn. But most in our day are not satisfied appealing to gods (or spirits) when some more mundane explanation is imaginable. God’s solution—creating from nothing—is truly Herculean … and we assume, impossible. We frame the problem instead as the reshaping of some raw material that’s already present in the world, including the raw material of pre-existing ideas.

Philosophers and critics addressing the question of creativity since the Enlightenment have largely adopted the idea that cultural innovation of whatever sort, when you really subject it to scrutiny, can be traced back to preexisting ideas, its pedigree masked by ingenious recombination and recontextualization. A kind of mechanistic, billiard-ball model of mental and cultural causation arose alongside the physicists’ Newtonian and thermodynamic models of physical causation. New ideas can always be traced back to other hidden sources, whether in other books or artworks or in the writer’s own earlier life experiences. In this view, there is really nothing new under the sun, just the old repackaged, rearranged, and repurposed.

Consequently, criticism, in emulation of physics, is more often than not the “debunking” of inspiration, the tracing of aesthetic causality and the lines of past influence leading to a poem or artwork or novel. Fearful of discontinuity, the critic is sometimes only satisfied when all possible influences are accounted for, lest there be any hint of creation ex nihilo—something gotten from nothing. For that is the real fear about artists in a Protestant, capitalistic society: that they’re slackers.

It’s that fear, I think, that gives rise to the sour truism constantly invoked to minimize artistic inspiration: Thomas Edison’s quip that genius is “one percent inspiration, and ninety-nine percent perspiration.” The right context, a favorable disposition, and persistence at a well-practiced craft are all-important. Forget the magic of those ideas that come to the artist unbidden, out of the blue, or in a dream.

The trouble is, the reductive Edisonian framework makes it very hard to explain myriad “prophetic” anomalies in the world of art and literature and popular culture, which look very much as though a creator, whether awake or dreaming, was reaching into their future, not the past … and doing it effortlessly.

Move Along, Nothing to See Here

I discussed several examples of literary prophecy in Time Loops. For instance, in 1951, after a long creative struggle with a novel that felt perpetually unrealistic to him, Norman Mailer published Barbary Shore, about a writer like himself living and working in a Brooklyn Heights rooming house with a colorful mix of artist neighbors, one of whom turned out to be a KGB spy. A few years later, after a stint in Hollywood, Mailer returned to the East Coast, to Brooklyn Heights, where he rented a room in a building to work on his next novel. He was stunned to encounter a New York Times headline about a top KGB Colonel named Rudolf Abel who had just been caught running a massive spy ring out of the same building he used for his office. He had known the spy as “Emil Goldfus,” the “guitarist” who worked one floor down from his studio.

We don’t normally expect visionary prophecy from a writer like Mailer, but Philip K. Dick was especially known for this kind of thing. To take just one of many examples, in 1962 he wrote a story about an android “simulacrum” of Abraham Lincoln but couldn’t find a publisher so the story languished unread in his desk drawer; two years later, Disneyland unveiled one of their most perennially popular exhibits, their “animatronic” Abraham Lincoln. When he read about this new exhibit, Dick clipped the article from the paper as proof that he was a “precog” straight out of one of his stories. (Previously on this blog, I’ve written about how Dick precognitively got the idea of “VALIS,” the extraterrestrial teaching satellite, from his reading of Jacques Vallee‘s Invisible College, 2-3 years after he began writing the first versions of that novel.)

We don’t normally expect visionary prophecy from a writer like Mailer, but Philip K. Dick was especially known for this kind of thing. To take just one of many examples, in 1962 he wrote a story about an android “simulacrum” of Abraham Lincoln but couldn’t find a publisher so the story languished unread in his desk drawer; two years later, Disneyland unveiled one of their most perennially popular exhibits, their “animatronic” Abraham Lincoln. When he read about this new exhibit, Dick clipped the article from the paper as proof that he was a “precog” straight out of one of his stories. (Previously on this blog, I’ve written about how Dick precognitively got the idea of “VALIS,” the extraterrestrial teaching satellite, from his reading of Jacques Vallee‘s Invisible College, 2-3 years after he began writing the first versions of that novel.)

The best-known case of literary prophecy is the novel Futility by sea-adventure writer Morgan Robertson. Published in 1898, Futility told the story of an alcoholic seaman working aboard the largest ocean liner ever built, the Titan, which hits an iceberg on an April night in the North Atlantic on a run between New York and England, killing nearly everyone aboard due in part to a shortage of lifeboats. Fourteen years later, the 51-year-old (and by then, largely forgotten) writer would have been nearly as stunned as his fellow New Yorkers by the New York Times headline reporting that the Titanic, with close to the same stats as the fictitious Titan, had carried most of its passengers to a watery grave under nearly identical circumstances to those in his novel.

Writers happen to leave a rich paper trail of prophecy, by the very nature of their work and their tendency to write or be interviewed about their lives, but it happens in all media. Recall for instance one of the funniest moments of the 1984 mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap: the descent onto the stage of a miniature Stonehenge model that had been made to the wrong proportions—18 inches instead of 18 feet—because a confused band member (played by Christopher Guest, who also co-wrote the movie) has used a double apostrophe instead of a single one on the back of a napkin. It could be one of the most weirdly prophetic moments in cinema.

Heavy metal insiders may have thought, when they viewed this scene, that the filmmakers were basing it on a real fiasco involving the band Black Sabbath that had occurred just six months before Spinal Tap‘s release: That band had planned to include a Stonehenge model in their concert tour for their Born Again album (one of the songs was called “Stonehenge”), but they were forced to shelve the idea at the last minute because the fake monument delivered to them was nine times too large—a result of a failure of communication between the band and the company commissioned to make the fake monument (the dimensions were supposed to be in feet but were interpreted in meters). Yet “impossibly,” Spinal Tap had already been written and shot by the time of Black Sabbath’s embarrassing mixup—including a version of the Stonehenge scene. So in other words, the movie idea for an embarrassingly mis-sized Stonehenge model (whichever member of the writing team thought of it) preceded the real-life Black Sabbath mishap by as much as a year.

Heavy metal insiders may have thought, when they viewed this scene, that the filmmakers were basing it on a real fiasco involving the band Black Sabbath that had occurred just six months before Spinal Tap‘s release: That band had planned to include a Stonehenge model in their concert tour for their Born Again album (one of the songs was called “Stonehenge”), but they were forced to shelve the idea at the last minute because the fake monument delivered to them was nine times too large—a result of a failure of communication between the band and the company commissioned to make the fake monument (the dimensions were supposed to be in feet but were interpreted in meters). Yet “impossibly,” Spinal Tap had already been written and shot by the time of Black Sabbath’s embarrassing mixup—including a version of the Stonehenge scene. So in other words, the movie idea for an embarrassingly mis-sized Stonehenge model (whichever member of the writing team thought of it) preceded the real-life Black Sabbath mishap by as much as a year.

Or less amusingly, take the 1999 sculpture Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian, by the African American sculptor Michael Richards. In this self-portrait, the artist depicted himself standing like a stiff board or tower, being pierced by a multitude of planes, much the same way St. Sebastian is depicted in Renaissance art as a pincussion of arrows. This piece has gained notoriety because of the tragic circumstances of the artist’s death on 9/11, in his 92nd-floor studio of 1 World Trade Center. Friends who had visited his studio before the attacks recalled several similar works on the themes of being martyred by planes, planes crashing, and explosions. Artworks and cultural ephemera from the months prior to 9/11 and appearing to depict its events are numerous.

The more one delves into artists’ and writers’ biographies—as I’ve been doing a lot this past year, preparatory to a book on this subject—the more one finds astonishing “synchronicities” that I believe are really cases of artistic precognition. The above cases (which can be found with a quick Google search) are just the tip of an enormous iceberg that includes some of the greatest writers and artists of our age (names like Kafka, Tolkien, Lynch, Herzog, and many others—watch this space).

100 Percent Masturbation

It’s amazing and a little sad to watch generations of academic scholars wrestle with the problem of creating the new from the old without invoking some purposive (let alone teleological) factor. Psychologists and other writers on creativity endlessly offer solutions acceptable to the essentially materialist, “enlightened” mentality of the time, and every one falls short, merely having found some new way of saying the same thing: Some faculty in the mind sees some new and pleasing possibility in materials at hand—influences, life experiences, etc.—and arranges them in some unexpected way. But the question “how did it see or find this new possibility amid the myriad available ingredients?” remains unanswered.

The time is ripe for a reassessment of creativity and its roots in precognition.

The time is ripe for a reassessment of creativity and its roots in precognition.

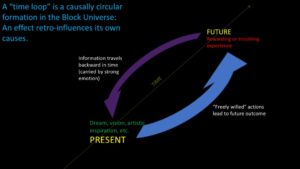

My argument in Time Loops is that our future thoughts and emotions in response to upheavals ahead get displaced in time and influence us in all the ways Freud attributed to “the unconscious.” It is best understood in dreams: Whereas Freud thought dreams symbolically represent repressed wishes and wholly relate to our past, I argue that they really represent responses to positive and negative turning points on the road ahead. However, since there is no way to fully grasp the meaning of information refluxing from our future—because only the future could give it context—the dreaming brain reaches into its grab-bag of memories and pre-existing associations to help it pre-present those alien-seeming thoughts. Dreams are thus like effigies of future thoughts sewn together from scraps of past experience, or “ruins” of future structures built from past bricks.

Our tesseract brains do the same thing when we create art, I believe. Artists, like dreamers (and we are all dreamers) are prophets, channeling their own future thoughts and emotions and traumas into material creations (images, stories, films, song, sculpture, whatever). Even though we can trace the past influences on a visionary work until the cows come home, those influences are simply the “bricks” with which a thought from the artist’s future is being pre-presented.

Intended as a satire on the pretentions of artists, William Tenn’s 1955 short story “The Discovery of Morniel Mathaway” expresses this time-looping logic through the trope of time travel: An art historian from the 25th century is awarded the privilege of traveling back several centuries to visit the Greenwich Village painter Morniel Mathaway, to study how the artist (the greatest ever, by late-25th-century standards) created his works. What the time traveler finds, however, is that Mathaway is a talentless fraud and a trickster, who instead of painting masterpieces simply cheats people, and he even steals the art historian’s time machine. Trapped in the past, the art historian has no choice but to simply assume the identity of Morniel Mathaway and paint the paintings he remembered from the future—thus, he himself is the master he had studied.

It’s more than just a trope. It has been known since Einstein that time machines are possible, in principle, and thus that the universe could be riddled with causal loops, the self-fulfilling prophecies known in physics-speak as closed timelike curves. You really could have a situation like what William Tenn described. The quantum computing pioneer David Deutsch described such a possibility in a 1991 paper, using a similar thought experiment: A Nobel Prize-winning mathematician travels back in time and finds his younger self toiling in some library over the very theorem that he will eventually win the Nobel prize for proving. To help his younger self out, the mathematician shows his younger self the proof.

Physicists who treat information and its conservation with a kind of holy reverence will be perturbed by such stories, as Deutsch appears to have been by his own story about the time-traveling mathematician. Deutsch found the “creation ex vacuo” of new information in his unproved-theorem scenario not paradoxical, exactly, but “pathological.” Where did the solution to the theorem originate? What was the source of this new information in the universe? Deutsch felt it violated Karl Popper’s dictum that “knowledge comes into existence only by evolutionary, rational processes.”

As Paul Nahin notes in his essential text Time Machines, the underlying anxiety here really arises from something like the work ethic—although I’d suggest it is more precisely Marx’s labor theory of value: “the creation of knowledge demands hard work!” In other words, what really bugged Deutsch was that there was nowhere in his gedanken-time-loop where anybody actually did the hard work of proving the theorem. There was no perspiration, in other words. The proof was self-caused. Fans of the outstanding Netflix series Dark will recognize this as the “bootstrap paradox”—in that show, the volume Eine Reise durch die Zeit (A Journey Through Time) by watch- and time-machine maker H. G. Tannhaus also evidently has no origin, having been transmitted to its author by a time traveler from the future.

As Paul Nahin notes in his essential text Time Machines, the underlying anxiety here really arises from something like the work ethic—although I’d suggest it is more precisely Marx’s labor theory of value: “the creation of knowledge demands hard work!” In other words, what really bugged Deutsch was that there was nowhere in his gedanken-time-loop where anybody actually did the hard work of proving the theorem. There was no perspiration, in other words. The proof was self-caused. Fans of the outstanding Netflix series Dark will recognize this as the “bootstrap paradox”—in that show, the volume Eine Reise durch die Zeit (A Journey Through Time) by watch- and time-machine maker H. G. Tannhaus also evidently has no origin, having been transmitted to its author by a time traveler from the future.

If the last century of physics has taught us anything, it is that physical reality does not play by the tedious rules that would prevent such things. For instance, the old conservation laws are increasingly thought to hold for delimited, well-defined physical systems, not the universe as a whole. New things constantly arise from nothing, without anyone doing a lick of work. Empty space, if you zoom way in, is really a seething “quantum foam” where layabout particles arise out of emptiness, uncaused, and undeserving. And matter and energy are all just information—so it violates nothing, really, to say that information can be created ex nihilo. It just … bugs us.

Tautologies, those lazy, unsociable, self-enclosed ouroboroses that fascinated ancient mystics, are not paradoxical. Neither is the kind of self-causation that is starting to look like the rule in physics, not the exception. Karl Popper, bless his heart, was simply wrong. And Deutsch’s discomfort with the pathology of information (although he really means meaningful information) arising from nothing is rooted in those fears of slack that pervade our work-ethic culture. They are also akin, I would add, to deep-seated worries and fears over masturbation—a pleasurable activity that doesn’t visibly produce anything for the community.

Thus the bootstrap paradox is a misnomer; being might even be bootstrapping, in the end. Thus there is no reason the labor theory of value, or the Protestant ethic, or really any kind of socially sanctioned “perspiration” needs to underlie the creation of new ideas.

I’m going to scandalize my stern, hard-working, penny-pinching Dutch Calvinist ancestors here and say that Edison’s quip about the effortfulness of genius is a total distraction, even an ideological one. To really understand creativity, we must move beyond the craft and industry metaphors—such as the toiling “guys in the basement” whom Stephen King credits for his ideas—and embrace the more ouroboric (/masturbatory) picture painted by modern physics. Just as the vacuum produces particles out of the void, for free, real creation produces the new out of nothing.

The creative germ or spark that gives rise to a novel, or a film, or a sculpture, or a song may in all cases be a time loop.

Prophecy’s Fractal Geometry

Even if we are open to the possibility that the artist creates precognitively, “from nothing,” it raises the question how a created work, like the created world, has positive features: Where does the uniqueness of a work of art come from?

There is a clue, I believe, right in our culture’s template for creation ex-nihilo, the 31st line of Genesis 1: “And He saw that it was good.”

When you drill down, many cases of artistic prophecy or precognition seem to follow a very specific, hindsight logic: novelists don’t just precognize any old thing; they precognize their reactions to their own works after the fact. Filmmakers precognize their own hindsight reactions to their films. And illiterate cowherds precognize how they will feel after delivering their poems to the local clerics.

It is worth noting that the theme of the verse that came to Caedmon in his dream was gratitude: gratitude toward the originator, for the wonders he had fashioned for the children of men. Wouldn’t gratitude precisely be how a shy, tongue-tied cowherd would have felt when suddenly recognized and embraced by his local ecclesiastical community as an original creator after presenting a poem essentially “given” to him by God? The poem that he had brought the local abbey, fractally about origins, from a man anxious of being unoriginal, transformed him into a celebrated member of his community; never more did he have to fear the approaching harp. But how could his dream “know” he would feel that way until after the events inaugurated by his dream?

I have come to think that creativity always works this way, obeying a kind of “fractal geometry of prophecy.” I’ve explored a few cases previously on this blog. When she was writing her novel Picnic at Hanging Rock, Joan Lindsay was literally dreaming about the conflicted emotions she would feel later about her novel, including the excision of its paranormal final chapter; the novel was based on those dreams. While there were certainly objective past influences on her story that could be traced and that gave form to her inspiration, at its heart was a void, an artistic semi-trauma in her future, very much like the fascinating three-dimensional “hole” in spacetime that beguiles her doomed lost girls atop the rock in the “missing” Chapter 18.

I have come to think that creativity always works this way, obeying a kind of “fractal geometry of prophecy.” I’ve explored a few cases previously on this blog. When she was writing her novel Picnic at Hanging Rock, Joan Lindsay was literally dreaming about the conflicted emotions she would feel later about her novel, including the excision of its paranormal final chapter; the novel was based on those dreams. While there were certainly objective past influences on her story that could be traced and that gave form to her inspiration, at its heart was a void, an artistic semi-trauma in her future, very much like the fascinating three-dimensional “hole” in spacetime that beguiles her doomed lost girls atop the rock in the “missing” Chapter 18.

Similarly, Harlan Ellison’s script for the Star Trek episode “City on the Edge of Forever” was, I believe, really about the hard feelings Ellison himself would experience as a result of bringing his creation into the world and submitting it to the “castrations” of Gene Roddenberry’s producing and writing team. It was a story about its own counterfactual future and, like Picnic at Hanging Rock, a time loop in the truest, purest sense.

All the various possibilities for the artist’s reaction to his/her work in hindsight will shape the work in different ways, push it in different directions, even if subsequent iterations and editing and reworking—the “perspiration” part—generally has the effect of effacing or obscuring this future influence, sanding it away or making it invisible. (It tends to be in the most “raw” and unpolished works that prophecy is most apparent.)

Underneath all these emotional possibilities, I believe, is amazement. In Time Loops I used the Lacanian idiom of jouissance to talk about our emotional timewarps, but I think amazement may be an even better term, especially as it applies to creativity. I think amazement could be the single most powerful time-transcending force in the lives of creators, the carrier of the psychic signal from their future to their past, in whatever final form that signal takes (a dream or a work of art, or both) or however it is (mis)interpreted. The unique form of an inspired work may derive partly from the specific nature of that amazement, the specific reaction of the creator to his or her creativity, to the impossibility at its heart. That reaction may be a kind of longing (as in Lindsay’s case), it may be confused anger and regret (as in Ellison’s case), it may be a kind of fear or anxiety, or even terror (looking at you, Mary Shelley). Or, as in Caedmon’s case, it may take the form of a kind of humble, awed thanks.

Critics always looking to the past and debunking human inspiration should turn around and look in the other direction instead. The possibilities of future influence in the world of art and literature are vast and (thus far) mostly unexplored, with just a handful of inspiring exceptions. Although he doesn’t use the term “precognition,” Malcolm Guite’s biography Mariner is a beautiful study of how Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” prefigured the poet’s life subsequent to the poem. In his book Philip K. Dick: The Man Who Remembered the Future, Anthony Peake details many of PKD’s prophetic novels and stories. The French writer Pierre Bayard’s Le plagiat par anticipation (Plagiarism by Anticipation) is a tongue-in-cheek exploration of retrograde literary influence (e.g., Sophocles got the idea of Oedipus from Freud, according to Bayard, not vice versa). And in the realm of music, Christopher Knowles has extensively explored the amazingly prophetic/synchronistic life and music of Cocteau Twins singer Elizabeth Fraser on his blog The Secret Sun, making a strong case that Fraser is a full-on sibyl … or something.**

More to come on this theme. But the bottom line is that I believe all art is prophecy, just as dreams are. By extension, so is thought. Our original ideas, our best thoughts, come from our future, not the past. We are made of time loops. And quite literally, we are something like gods, creating ex nihilo whenever we are gripped by inspiration or make art or music or write from “the unconscious.”

NOTES

* If he really existed, Caedmon probably wasn’t his real name, for one thing. He was likely bestowed this name by those clerics, or even by posterity, after the Greek Cadmus, the legendary bringer of the alphabet to the people.

** I wholeheartedly agree with Knowles about the preternatural Liz Fraser. But I also think she had precognitive help: 4AD founder/producer Ivo Watts-Russell seems to have shown the same hyper-precog qualities Fraser did, but he expressed it mostly through identifying talent and launching others’ musical careers.

SOURCES

Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People

David Deutsch, “Quantum mechanics near closed timelike lines,” Physical Review D (15 Nov, 1991)

Paul Nahin, Time Machines

Martin Schneider, “Life imitates comedy: Spinal Tap uncannily anticipated Black Sabbath’s very own Stonehenge debacle”

William Tenn, “The Discovery of Morniel Mathaway,” Galaxy Science Fiction (October 1955)

John H. Wotiz (ed.), The Kekule Riddle

This post is based on a talk, “Creativity and the Precognitive Mind,” given at Esalen in January, 2019.

Excellent article. I hadn’t heard most of those examples before. Spinal tap and the sculpture, almost spooky. I’ll try to keep it brief. My job does not require the use of my brain. To minimize “monkey mind” and possibly get somewhere, I pick a subject to meditate on. One is, can you really imagine anything new? For example, you can imagine a green two headed cow. It may be new, but it’s built from used parts. So far, for myself, being honest, the answer is no. The wildest fantasy is assembled from previous experience. If or how this relates to precognitive art, I don’t know.I just thought I’d throw it out there.