Quantum Psychoanalysis: Interpreting Precognitive Dreams

Near the end of Christopher Nolan’s 2014 film Interstellar, astronaut “Coop” is able to communicate with his younger self (as well as his daughter) decades in the past using a tesseract, a theoretical multidimensional portal created by our descendents thousands or millions of years in the future. Coop’s messages are oblique—he can’t address his younger self directly but has to send symbolic messages using the books on his bookshelf. His younger self, before his planned mission to a black hole, realizes there something significant occurring but misses the precise meaning of these messages: a warning not to go.

The character of the brain’s self-relating across time is allusive and indirect: We don’t just appear to ourselves bearing explicit messages from the future; messages from our future self are oblique, more like a game of charades.

If the brain is a quantum computer, the possibility I discussed in the last post, it could work by creating coherent systems of entangled particles that are isolated enough, for long enough, that they are able to manipulate information in ways far beyond what conventional computers can achieve, including sending coherent information into the past and extracting information arriving from the future. Whether or not the mechanism is precisely the one I proposed, based on Seth Lloyd’s theory of time travel via quantum teleportation, I predict that some form of trading and extracting of coherent information across time may turn out to be a basic function of the cortex, a picture that could provide a radically new understanding not only of psi but also of memory and other basic cognitive functions. The brain may be precisely something like Nolan’s tesseract, an organ that is genuinely a tunnel through time, extending across our whole lifespan.

So at the risk of sounding like a reductive materialist bad-guy (which, honest, I’m not), I do think the answer to psi (not necessarily consciousness) is going to be found in neuroscience. All the evidence points to this. No energy transmission or reception has ever been found to account for psi. The physics of information that governs psi and synchronicity has nothing to do with “thoughts through space,” the airy mental image most of us probably have when we think of psychic phenomena. We need to get rid of that mental model of waves radiating from or toward a head. The brain may not create consciousness, but it certainly gives shape to our conscious experience, in the form of memory, thoughts, symbol use, sense of self, and so on. Our experience is processed and shaped by the brain, so our future experiences are mediated by our brain in the future.

I see a brain-based theory of psi as a more compelling alternative to “nonlocality” theories commonly invoked by parapsychologists. Even if it is true that all points in space and time are connected, that gets us no closer to explaining how psi works—for example, how a remote viewer given an arbitrary code word can home in on and describe a specific geographical target that the code word represents, among all possible targets in the universe (and that she hasn’t seen before and couldn’t possibly “recognize”); or how a mother could have a vision of her own dying son on a battlefield (and not all dying people everywhere); or why people have premonitions not of major disasters but specifically of their own reading of those disasters in the news (J.W. Dunne’s major discovery in his 1927 book An Experiment With Time). None of this has anything to do with nonlocality; it’s a matter of information search and retrieval, and it reveals how intimately personal psi information is—we are “recollecting” information from a future point in our own timeline when we will learn something we don’t yet know and don’t yet even know we want to know.

I see a brain-based theory of psi as a more compelling alternative to “nonlocality” theories commonly invoked by parapsychologists. Even if it is true that all points in space and time are connected, that gets us no closer to explaining how psi works—for example, how a remote viewer given an arbitrary code word can home in on and describe a specific geographical target that the code word represents, among all possible targets in the universe (and that she hasn’t seen before and couldn’t possibly “recognize”); or how a mother could have a vision of her own dying son on a battlefield (and not all dying people everywhere); or why people have premonitions not of major disasters but specifically of their own reading of those disasters in the news (J.W. Dunne’s major discovery in his 1927 book An Experiment With Time). None of this has anything to do with nonlocality; it’s a matter of information search and retrieval, and it reveals how intimately personal psi information is—we are “recollecting” information from a future point in our own timeline when we will learn something we don’t yet know and don’t yet even know we want to know.

Psi is thus fundamentally memory-like in the way it behaves. Just as we can only remember our own past and not other people’s pasts, we can only remember our own future. And besides being personal, psi is also associative—again, just like memory.

Free Association

As in Nolan’s tesseract, the character of the brain’s self-relating across time is allusive and indirect: We don’t just appear to ourselves bearing explicit messages from the future; messages from our future self are oblique, more like a game of charades. They may need to be, to conform to the rules that govern memory, and to conform to the demands of “post-selection”—that is, not allowing an action that would foreclose the message from being sent. It’s not like there’s a “precognition police” enforcing this; it’s more like informational Darwinism: the only precognitive messages that “survive” are the ones that lead to their being sent back in time in the first place. Among the parameters of such a tesseract would be a tendency for the clearest examples of precognition to be only consciously recognizable after the fact, unless there is no possibility of preventing the future outcome in which information was sent to the present.

The fact that so much precognitive dream material comes to light when using free association suggests that precognitive dreaming occurs far more frequently than even its advocates typically assert.

Precognitive dreams illustrate this principle marvelously. The basic function of dreaming appears to be the updating of the brain’s associative search system that catalogs and files daily autobiographical events by linking them to other events (and themes) in our long-term memory. Although isolated elements may be immediately recognizable as “day residues,” dream episodes never literalistically represent events, but are tableaux assembled from memories and images those events remind the unconscious of—exactly the kinds of distortions and displacements that Freud mis-took as symbolic disguises for repressed wishes. But even if dreaming’s function is basically mnemonic and not wish-fulfillment, mnemonic associations are formed through precisely the types of puns and other substitutions that Freud identified. Precognitive dreams obey the same principles, and this is why free-association is invaluable in uncovering the true extent of our our nightly precognizing.

Standard Freudian dream interpreters, being entirely past-looking—and biased to search for disguised wishes—are liable to completely miss the large number of precognitive dreams we have on a nightly basis. I now suspect that a sizable portion, maybe even half, of our dreams actually encode events of the subsequent day or farther out, but this is inevitably missed if we do not return to our dreams at later intervals (especially the following afternoon or evening) with an eye to searching for this material.

Standard Freudian dream interpreters, being entirely past-looking—and biased to search for disguised wishes—are liable to completely miss the large number of precognitive dreams we have on a nightly basis. I now suspect that a sizable portion, maybe even half, of our dreams actually encode events of the subsequent day or farther out, but this is inevitably missed if we do not return to our dreams at later intervals (especially the following afternoon or evening) with an eye to searching for this material.

You don’t need to contort or “twist” a dream to find precognitive referents. Contrary to what Freud-bashers always assert, free-association is not (when it is done right) straining to come up with “meanings” that will lead to a desired conclusion. You do have to play by the rules though: Only the first thing that comes to mind for a noticed dream element is a valid connection. If the first things that come to mind for various dream elements don’t suggestively illuminate a dream episode, just leave it. Many dreams are smarter than we are, and we have to concede defeat; others may refer to events that haven’t happened yet, so we can never assume that the right answer is findable. But when done in good faith, free association reveals abundant precognitive material in dreams that would otherwise go unnoticed.

A particularly clear example from my dream journal from this past April will serve to illustrate the process. (Apologies in advance—I hate reading other people’s dreams, and I know you do to…)

Petroglyph Dream

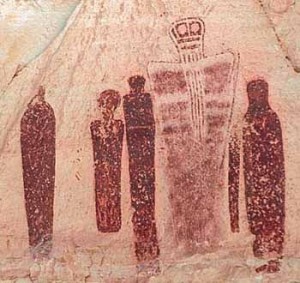

On my way up a mountain, I had stopped at a roadside tourist attraction, a cave with ancient Indian petroglyphs on the ceiling, the most prominent being an enormous elongated/tall rectangular ‘man’ or headless being of some sort, reminding me of one of those elongated tall shaman figures in Southwest rock art [like the middle figure in the picture below], and then a smaller object higher above that figure that I found less interesting. I didn’t have my camera with me (specifically, my old Pentax, which I knew was loaded with black and white film), but I thought I could get it somewhere farther up (the mountain); so I resolved to stop on my way back down so I could take black and white pictures of the petroglyph.

The scene changed: I realized I had my iphone in the car so I retrieved it and attempted to take color pictures in the cave. No matter what I did, however, the screen kept “repelling” my attempt to photograph the largest (tall, vertical) petroglyph that interested me. I turned the camera around to use the front-facing camera, but it still only showed my face on the screen, as though there were a force field preventing any image of the actual petroglyph. Then I dropped the phone and damaged the side, where a button is.

The scene shifted again: I was inside a visitor’s center at the “top” of the mountain, but associated with the cave. It was circular in plan, and around the outer ring were various vestibules with stuff for sale, including snacks. I found a coffee-flavored drink to buy. I thought there might be something else interesting in one of the other rooms, so I went searching, and circled the whole visitor’s center and came back to where I’d started, disappointed.

On writing down the dream initially, the only association that immediately came to mind was the “unphotographable petroglyph”: Two decades ago, when living and working in Eastern Europe, I had a coworker friend named Petra who refused to be photographed; my only picture of her shows her with her face turned away and her hand held up to block the camera. Thus “petroglyph” seemed to be a kind of dream representation of Petra, a “Petra picture.” There was no reason in my current life to be thinking of this old coworker, however. It was later that afternoon that the primary event-referent of the dream became clear.

On writing down the dream initially, the only association that immediately came to mind was the “unphotographable petroglyph”: Two decades ago, when living and working in Eastern Europe, I had a coworker friend named Petra who refused to be photographed; my only picture of her shows her with her face turned away and her hand held up to block the camera. Thus “petroglyph” seemed to be a kind of dream representation of Petra, a “Petra picture.” There was no reason in my current life to be thinking of this old coworker, however. It was later that afternoon that the primary event-referent of the dream became clear.

I had taken time away from my work to watch the live web coverage of a SpaceX launch from Cape Canaveral, which would be delivering a cargo module to the International Space Station. It was somewhat exciting, as all rocket launches are, but my main reason for watching this launch was my expectation—based on some Twitter postings earlier that day—that SpaceX might also broadcast the attempted landing of the first stage of the rocket on a barge in the Atlantic; this retrieval method had failed the previous two attempts, but there were high hopes for success in this case. After the launch the cameras on board the rocket showed the first stage separation, but the only views subsequently shown were shots of the exterior and interior of the orbital Dragon module; several minutes passed, and I became increasingly frustrated when the cameras didn’t cut away to show the first-stage retrieval I had been excited to see. It became apparent that, despite the misleading publicity on this launch, the SpaceX broadcast was not going to show the landing, no doubt because of the uncertainty of the outcome.

In the aftermath of my frustration at being unable to view the first-stage landing/retrieval, I realized that my petroglyph dream had been about this minor emotional salience in my otherwise uneventful workday, and thus my frustration turned to excitement. The shape of the bottom/main petroglyph I was interested in, in the dream, was exactly like a tall first stage of the rocket with a flat top. In the dream, the object of my interest resisted being photographed/viewed, like my friend Petra many years before, and thus the dream concocted an amalgam of these two ideas: a “Petra picture,” placed overhead on the roof of a dark cave (like the sky), which my iPhone (a small computer/camera) was unable to capture in its screen. (Remember that there was also a smaller object up above the tall “man” that I found less interesting.) One of Freud’s key insights was that the unconscious cannot represent or conceive an absence; it must put an object in its place—in this case a cave roof for the empty sky, narratively consistent with the “petroglyph” idea that was itself required by the pun on Petra picture, perfectly fit the bill.

In the aftermath of my frustration at being unable to view the first-stage landing/retrieval, I realized that my petroglyph dream had been about this minor emotional salience in my otherwise uneventful workday, and thus my frustration turned to excitement. The shape of the bottom/main petroglyph I was interested in, in the dream, was exactly like a tall first stage of the rocket with a flat top. In the dream, the object of my interest resisted being photographed/viewed, like my friend Petra many years before, and thus the dream concocted an amalgam of these two ideas: a “Petra picture,” placed overhead on the roof of a dark cave (like the sky), which my iPhone (a small computer/camera) was unable to capture in its screen. (Remember that there was also a smaller object up above the tall “man” that I found less interesting.) One of Freud’s key insights was that the unconscious cannot represent or conceive an absence; it must put an object in its place—in this case a cave roof for the empty sky, narratively consistent with the “petroglyph” idea that was itself required by the pun on Petra picture, perfectly fit the bill.

That the petroglyph dream element referred to the first stage of the SpaceX rocket is clinched by my desire/intention in the dream of getting my old Pentax camera and photograph it in black and white. This was a very specific memory reference to watching a space shuttle launch in Orlando Florida in the late 1990s, which I had photographed with my Pentax, not remembering it was loaded with black and white film—producing very disappointing lackluster photographs of what was a colorful and spectacular sight. (I have not used that Pentax camera in many years, and that frustrating event was my strongest “free association” with that camera.) In the dream, I specifically wanted to get my Pentax to photograph it “on the way back down”—displacing the rocket’s “way back down” with my own way back down the mountain.

That the petroglyph dream element referred to the first stage of the SpaceX rocket is clinched by my desire/intention in the dream of getting my old Pentax camera and photograph it in black and white. This was a very specific memory reference to watching a space shuttle launch in Orlando Florida in the late 1990s, which I had photographed with my Pentax, not remembering it was loaded with black and white film—producing very disappointing lackluster photographs of what was a colorful and spectacular sight. (I have not used that Pentax camera in many years, and that frustrating event was my strongest “free association” with that camera.) In the dream, I specifically wanted to get my Pentax to photograph it “on the way back down”—displacing the rocket’s “way back down” with my own way back down the mountain.

Although the first-stage retrieval was not televised, news tidbits trickled in via Twitter that the barge landing had failed; one person on Twitter said they “broke the rocket.” It was revealed that the rocket had hit hard, with too much lateral momentum, and fallen over on its side. In the dream, I dropped my phone and broke it, specifically the button on its side. (A few days later, video was made available showing the interesting and highly entropic outcome of the failed landing attempt: the rocket descending onto the barge but falling over and exploding.)

Although the first-stage retrieval was not televised, news tidbits trickled in via Twitter that the barge landing had failed; one person on Twitter said they “broke the rocket.” It was revealed that the rocket had hit hard, with too much lateral momentum, and fallen over on its side. In the dream, I dropped my phone and broke it, specifically the button on its side. (A few days later, video was made available showing the interesting and highly entropic outcome of the failed landing attempt: the rocket descending onto the barge but falling over and exploding.)

The last part of my dream, about traversing a circular gift shop “at the top of the mountain” and finding a coffee drink, is also directly significant. The main media-worthy fact about this SpaceX mission, which was part of the chatter during the launch coverage, was that it was going to be delivering an espresso machine to the International Space Station. During the coverage, at the point of my maximal frustration (i.e., when I hoped it would cut away to show the barge retrieval), what was shown instead was a boring, somewhat ambiguous viewpoint inside the circular cargo module, along its visibly curved edge (i.e., my frustration and disappointment at circling the circular gift shop and finding nothing but a coffee drink).

Thus, as is typical with dreams, various old memory fragments with resonances to an emotionally salient autobiographical situation (inability to see/photograph a friend; failure to satisfyingly photograph a rocket launch) were woven together by the unconscious to create an associative symbolic tableau, rather like a game of charades hinting strongly at a core autobiographical event that is not directly represented; but in this case the event was a few hours in my future, not the previous day or two as is the somewhat more familiar and typical pattern.

Psi has always been noted to involve emotional upheavals of various kinds, and to especially express itself when ordinary communication channels prove limiting or frustrating—both of these characterized the autobiographical episode this dream seemed to be pre-encoding. (The connection between new communications technology and psi is a whole topic in itself, of course; in the early days of the ARPAnet, Jacques Vallee noted telepathy occurring among networked chat users.) Also, there is a distinct connection between precognitive information and highly “entropic” events like rocket launches and explosions, as Edwin May has shown. Many (although not all) of my own precognitive dreams involve entropy gradients in one way or another—often an entropic event on the news, or indeed on Twitter—although I believe this has less to do with our “psi eyes” and more to do with the kinds of information we as humans find interesting and survival-relevant, whatever the sensory channel. True to form, this dream managed to draw together multiple lines of association to express the idea of a disappointing or frustrating failure to fully see what I wanted to see—a camera being a standard representation of “seeing”—precisely in connection with a rocket launch and landing.

Dunne Right

Note that there is nothing immediately obvious in the above dream that would connect it with what I am asserting was its future referent; like most precognitive dreams, it would have gone completely unnoticed had I not been in a habit of (a) recording my dreams, (b) unpacking my dreams via free-associative Freudian methods, and (c) revisiting them later in the day in search of possible precognitive references. Again, a dream is not a literal replay of an event (past or future), but the firing of neural circuits that in one way or another closely associate to that memory (or its themes)—wiring these associations together by firing them together. Dreaming is the experience of neural rewiring, the updating of the search system, and thus the actual autobiographical episode they relate to is generally not represented and thus not obvious at first glance; the dream is a kind of associative halo around the event, and the event is a kind of blank space at its heart.

Unacceptable emotions about 9/11 may have been sacrificed to the past, retroactively giving rise to the countless premonitory and precognitive dreams and visions experienced by Americans during the previous days and weeks.

Dreams in which you can discern the precognitive referent without any kind of free-associative unpacking are infrequent, but even those are common enough that a casual dream-recorder can occasionally discover them. J.W. Dunne gave no thought to Freudian methods of dream interpretation, for instance, yet recorded several plainly precognitive dreams that had very little symbolic/associative ‘disguise.’ Dale Graff, who was a director and remote viewer in the Star Gate program, has written extensively of dream precognition and precognitive remote viewing using dreams in his excellent memoirs Tracks in the Psychic Wilderness and River Dreams, and he also describes several examples in which the target is plain without the use of free association.

The fact that so much precognitive dream material comes to light when using free association suggests that precognitive dreaming occurs far more frequently than even its advocates typically assert. In my case, not a week goes by when I do not record at least a few dreams like the above, that clearly refer (once unpacked) to an event the following day. Typically these events are trivial, not the sort of thing you’d imagine warranted a warning or alert, and certainly lacking the “numinous” quality commonly associated with premonitory dreams. Even the most assiduous dream recorder only remembers and records a small handful of his/her dreams each night. We may dream for a few hours each night but, in my case, I suspect my recorded dreams amount to only a tiny fraction of that total—perhaps a few minutes worth of narrative. Thus I suspect strongly that we are, all of us, probably precognitively dreaming (in addition to retrocognitively dreaming) in abundance. It’s probably a basic function. The trouble is that dreams are very hard to remember and are otherwise highly recalcitrant to study, for a host of reasons.

The fact that so much precognitive dream material comes to light when using free association suggests that precognitive dreaming occurs far more frequently than even its advocates typically assert. In my case, not a week goes by when I do not record at least a few dreams like the above, that clearly refer (once unpacked) to an event the following day. Typically these events are trivial, not the sort of thing you’d imagine warranted a warning or alert, and certainly lacking the “numinous” quality commonly associated with premonitory dreams. Even the most assiduous dream recorder only remembers and records a small handful of his/her dreams each night. We may dream for a few hours each night but, in my case, I suspect my recorded dreams amount to only a tiny fraction of that total—perhaps a few minutes worth of narrative. Thus I suspect strongly that we are, all of us, probably precognitively dreaming (in addition to retrocognitively dreaming) in abundance. It’s probably a basic function. The trouble is that dreams are very hard to remember and are otherwise highly recalcitrant to study, for a host of reasons.

For one thing, the dreamer is an n of 1, and his/her associative language is unique, and thus it can take years of working with one’s own dreams to get a sense of their character. And critics will always be able to accuse you of making your interpretations up. The “n of 1” problem is what makes Freudian dream interpretation—as well as its variant, mnemonic dream interpretation—inherently untestable. No dream can be replicated, and multiple dreamers will dream about the same experience in totally unique and idiosyncratic ways. The most basic support for the mnemonic theory, however, is in its consistency: If one dream element associates to a particular event in daily life, the remainder of the elements in the same dream episode almost always refer to that same episode or to the same narrow window of time. Again, this is because they are not wish-fulfillments but bundled episodic memories being processed and accessioned by the hippocampus. The hippocampus is like our autobiographical librarian; dreaming is like that librarian taking a new book/event, stamping it with a bar code and scanning it into the system, before placing it on the appropriate shelf; our dreams are those bar codes.

Also, dreams are hard to fully unpack in public or outside a therapeutic context because they touch on very personal, private symbolism that is just too difficult to explain to others to make it worth the trouble. I chose the “Petroglyph” dream not because it is the most stand-out example but because the symbolism in it doesn’t happen to be that embarrassing or personal (although it still strains the “TMI” limits that make another person’s dream-interpretations always annoying or embarrassing to hear). Most are much worse from the sharability standpoint. This is why the psychoanalytic literature is such an important augmentation to Dunne and the rest of the parapsychological literature bearing on precognition. Jule Eisenbud’s books Psi and Psychoanalysis and Paranormal Foreknowledge are full of compelling examples taken from his own case files.

The bottom line is that precognition is normal and constant, but is highly personal, like memory, and manifests indirectly and unconsciously. We are undoubtedly also receiving precognitive information across the course of the day that never gets expressed in any conscious form but primes us for action and thought in numerous invisible ways. This is the “first sight” logic described by James Carpenter, which is supported by numerous presentiment studies such as those by Daryl Bem, Dean Radin, and Julia Mossbridge. So-called synchronicities, of course, are misrecognized precognition’s main, most visible symptom.

Precognition and Repression

This is more speculative, but I have a hunch that those associative rules that govern memory and precognition may have a specifically “quantum” rationale in information theory. On the quantum level, in a closed, coherent system such as a quantum computer, information cannot be lost or destroyed, but only “traded” back and forth through time, and thus post-selected information would specifically transfer back in time and disappear from the present. The ongoing fluidity and flux of memory could be a product of information obeying quantum (or quantum-like) rules, even if association itself really involves macro-scale, classical dynamics.

Precognition may even be the flip side of repression: Repression would be a process of trading unwanted data into the past, and precognition would be the corresponding process of receiving that repressed information from the future.

The brain’s ongoing process of time-binding may thus involve acquiring information from the future at the price of loss of information in the present and losing information in the present to the past when new information is acquired—such as an emotionally salient (i.e., memorable) autobiographical event. If some function of attention is able to make determinations about what part of that new information to keep in the present, then precognition would be linked with this preference system. This would give us reason to link the Freudian concept of “repression” to this process of making choices about the dispersal of information in time.

It may even be that precognition is the flip side of repression: Repression would be a process of trading unwanted data into the past, and precognition would be the corresponding process of receiving that repressed (and hard to interpret) information from the future. Or you could say, precognition is the appearance of new information without knowing the cause, whereas repression is a cause that seems to somehow lose its effect by losing part of its affect.

If this is so, we would be especially precognitive for events that are too “explosive” (in multiple senses) and that we do not want to fully confront or face right when they happen. As I discussed in my “Trauma Displaced in Time” article, the splitting of our reaction to traumatic events like disasters may cause any positive emotion connected with them to “travel” into the past and emerge as premonitory or precognitive information before the traumatic event occurs. A range of positive feelings like excitement, thrill, and arousal were stimulated by news coverage of the terror attacks on 9/11, for instance, particularly for those who didn’t have loved ones possibly affected by the disaster. These unacceptable emotions may have been partially or wholly sacrificed to the past, retroactively giving rise to the countless premonitory and precognitive dreams and visions experienced by Americans during the previous days and weeks.

If there were any way to test it, I would bet money that 99 percent of Americans dreamed of the terror attacks on the night of 9/10/2001; the thousands who actually reported their premonitory dreams of the event were just a fraction of those that noticed such dreams and didn’t report them, which would itself be a tiny fraction of those who had dreams associatively linked to the themes of the day without ever noticing the link … and that would be a tiny fraction of those who had such dreams but didn’t remember them at all, and so on. (There should a be Drake Equation for precognitive dreaming.)

In fact, in keeping with my current obsession with “Twitter dreams” (which I seem to have a few times a week), I think part of that unacceptable emotional energy around disasters might be the frenetic, dopamine-induced excitement we feel when they are unfolding, particularly stoked by TV and new media like Twitter. Although we outwardly express grief and shock, it is the savage (but really, highly adaptive) eagerness to “find out more” that keeps us engaged with unfolding tragedies like terror attacks. That excitement, if my hunch is right, may be a lot of what gets shunted to the past.

In fact, in keeping with my current obsession with “Twitter dreams” (which I seem to have a few times a week), I think part of that unacceptable emotional energy around disasters might be the frenetic, dopamine-induced excitement we feel when they are unfolding, particularly stoked by TV and new media like Twitter. Although we outwardly express grief and shock, it is the savage (but really, highly adaptive) eagerness to “find out more” that keeps us engaged with unfolding tragedies like terror attacks. That excitement, if my hunch is right, may be a lot of what gets shunted to the past.

Straightforward excitement at a reward or achievement in the process of skilled engagement can also be traded into the past for another reason. Anyone who does a martial art or writes creatively or performs any high-stakes skill (flying a plane, performing brain surgery, etc.) knows that requirement of successful skill-engagement is “curbing your enthusiasm”—not allowing yourself the luxury of celebrating small successes in the moment but staying coldly focused. Thus, just like with traumas but for different reasons, rewards may pass excitement back into the past or future, accounting for the greater emergence of highly adaptive precognition in these flow states, consistent with the “first sight” idea. Just a hunch.

POSTSCRIPT: Does Longevity = Processing Power?

I realize it is highly out of fashion to liken the brain to a computer, but quantum computing may breathe new and interesting life into that metaphor. If the brain can reach across its own timeline, accessing information in its future and past, then it could be characterized as a fully four-dimensional information processor, able to utilize all its computing power over its whole lifespan, not to mention capitalize on all the other fantastical abilities of “qubits.” If the brain is a quantum computer (or more likely, an assemblage of billions of quantum computers linked classically)—and if it thus can, at any given moment, utilize all of its states across time, as well as all possible paths to obtaining the answer to a search query in memory—then not only its precognitive capabilities but its computing abilities in general would be formidable indeed.

Mentally, we are in the after-life, displaced (milliseconds, seconds, hours, even years sometimes) from the classical billiard-ball unfolding of our physical bodies.

It is already well known that, in humans, intelligence correlates with longevity; although obvious commonsensical explanations, such as smarter individuals being better able to avoid dangers, are no doubt operative, some research has found a common genetic factor uniting them. The notion that brain could be a quantum computer “calculating” across its whole history raises a further possibility: that longer lifespan causes higher intelligence by increasing the four-dimensional computing resources of the individual’s brain. This could perhaps provide an alternative explanation for the genetic correlation.

I am opposed to frivolous animal experiments, but purely as an animal-thought-experiment, you could test this idea by assessing the intelligence or problem-solving ability of a group of identical animals (cloned mice, for instance), and then sacrifice a randomly selected half of the group immediately after the assessment, letting the remainder live a full life. If their brains are making computations drawing on the computing power of a whole mouse lifetime, the long-lived mice would be hypothesized to perform better than the short-lived ones. A more ethical variant of this type of experiment would be to randomly expose half the mice to a condition of more learning and a more enriched environment following the test. Essentially, some of Bem’s experiments with college students in his famous “Feeling the Future” research program have shown such benefits of subsequent learning on prior performance.

I am opposed to frivolous animal experiments, but purely as an animal-thought-experiment, you could test this idea by assessing the intelligence or problem-solving ability of a group of identical animals (cloned mice, for instance), and then sacrifice a randomly selected half of the group immediately after the assessment, letting the remainder live a full life. If their brains are making computations drawing on the computing power of a whole mouse lifetime, the long-lived mice would be hypothesized to perform better than the short-lived ones. A more ethical variant of this type of experiment would be to randomly expose half the mice to a condition of more learning and a more enriched environment following the test. Essentially, some of Bem’s experiments with college students in his famous “Feeling the Future” research program have shown such benefits of subsequent learning on prior performance.

In keeping with my “Libet’s Golem” speculation, perhaps we ought to think of baseline cognition as displaced into the future. Maybe instead of pre-cognition we should talk about post-activity. Mentally, we are in the after-life, displaced (milliseconds, seconds, hours, even years sometimes) from the classical billiard-ball unfolding of our physical bodies. Yet we are never directly aware of that because all the physical data from our senses, which could be used to fix us in time, belongs to that “past” body locked in its classical time zone, it’s singular moment of “now,” which provides all of our reference points (unless we are in an altered or meditative state). This narrow sensory window misleads and confuses us about what we are, and when we are.

In other words, the present moment refers to the coordination of our senses, not to the “when” of our subjectivity and thought. Yet our only window onto the physical world is at one time, the conventional social “now,” the singular cursor in our life’s video-editing timeline. Yet the place of thought may be that whole world-line of the brain, from start to finish. We have no way of seeing that, except indirectly, in oblique paranormal phenomena where the other times of our mind push through into conscious awareness because our defenses against psi have momentarily broken down.

Interesting article. I think I might be getting confused by assuming “computer” means “Turing Machine”.

Though it seems to me there are two levels of potentially incompatible explanation – one on the level of quantum mechanisms, the other pertaining to existing minds repressing and interpreting information?

I’d lean toward the latter explanation myself, as I don’t see how there is any information without minds being informed?

Of course the seeming incompatibility could easily be lack of understanding on my part.